Friends,

Ten years ago, as the Fight for $15 was just beginning, one of the biggest obstacles that fast-food workers had to overcome was the media bias against raising the minimum wage. Virtually every story about protests and political actions included a lengthy conversation with an economist who warned that raising the wage would kill jobs, hurting the very people the wage was intended to help.

We know that none of those concerns are true. But the economics profession has for decades been steeped in trickle-down talking points that place CEOs and the super-rich, not working Americans, at the center of the economy. Under that model, anything that takes money away from the wealthy folks at the top of the company—including wages—is bad for the economy. So journalists, in an effort to both-sides the minimum wage debate, talked with a seemingly endless supply of credentialed economists just waiting to explain how dangerous raising the wage was.

I say all that in order to set up some context for this quote from a story by Ben Casselman and Lydia DePillis in yesterday’s New York Times:

When the Fight for $15 movement began, many economists warned that raising the minimum wage too high or too quickly could lead to job losses. Some studies did find modest negative effects on employment, particularly for teenagers and others on the margins of the labor market. But for the most part, researchers found that pay went up without widespread layoffs or business failures.

For the paper of record to publicly acknowledge that there is no tradeoff between raising the wage and killing jobs or closing businesses was absolutely unthinkable a decade ago. It’s a sign of how far the mainstream economic understanding has shifted—and with it, the media’s understanding of how the economy really works.

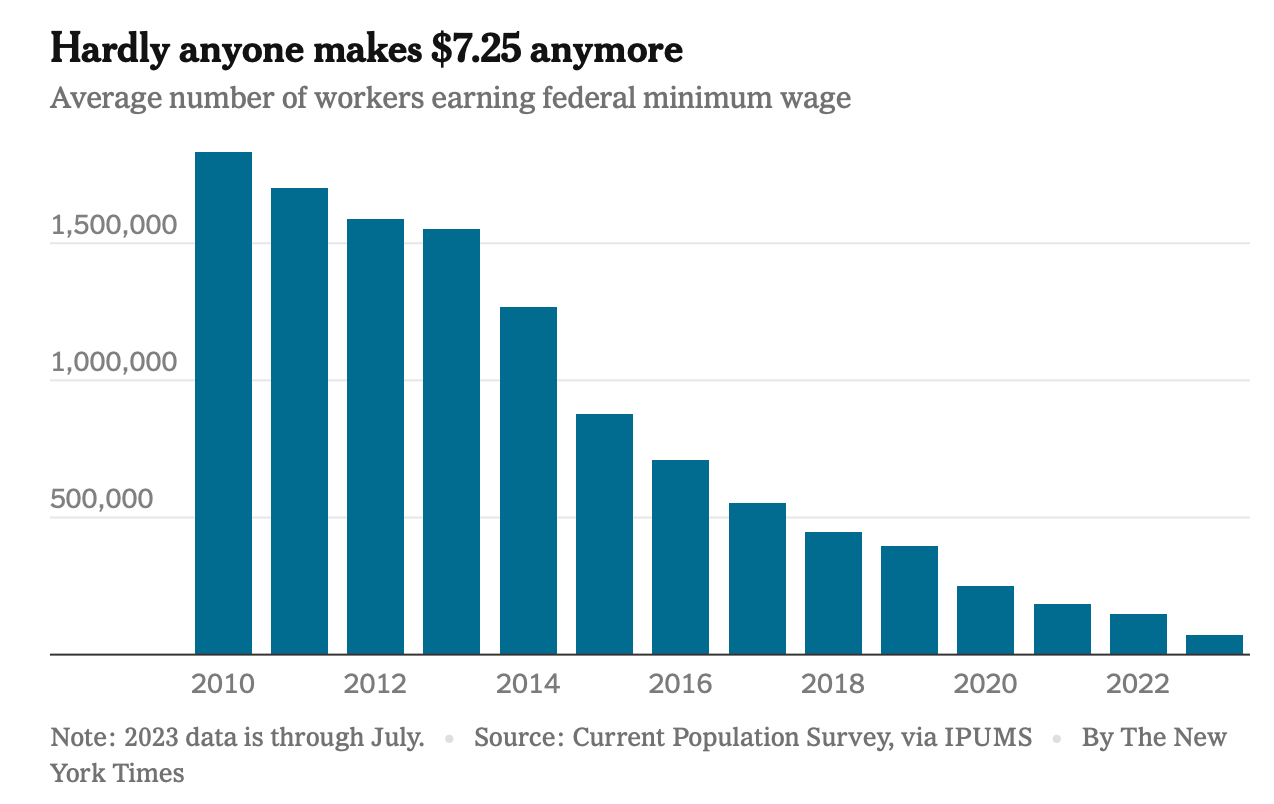

Unfortunately, the story surrounding that astonishing quote is built on another wrong-headed assumption: Casselman and DePillis write that since “only about 68,000 people on average earned the federal minimum wage [of $7.25 an hour] in the first seven months of 2023,” the booming job market has rendered the federal minimum wage—and many high regional minimum wages—” increasingly meaningless.”

The Times considers this chart to be a sign that employers are forced by the labor market to pay more than the minimum wage…

…when really, all it proves to me is that trickle-downers have held the federal minimum wage so low that it’s essentially becoming obsolete—which is probably their plan.

The problem is that the federal minimum wage has a very long tail. By focusing on how few Americans earn $7.25 per hour, the Times is neglecting the four million American workers who still make less than $10 per hour, and the almost one-third of American workers who earn less than $15 per hour—most of whom are nonwhite and women. Just because they don’t make the absolute minimum allowed by law doesn’t mean their paychecks are big enough to survive in a nation where costs have skyrocketed over the last two years. The Times also seems to ignore all the workers who still earn less than the $7.25 minimum wage—specifically, disabled workers and former felons, along with workers who earn the $2.13/hour federal tipped minimum wage.

The workers who have been left behind in the Fight for $15’s push to raise the wage in states and cities around the country are workers in red states and cities who will likely never see a meaningful raise unless the federal minimum wage increases. The Times’s thesis that the minimum wage doesn’t matter ignores all these workers.

Raising the minimum wage is popular with American voters, and by the Times’s own admission, it doesn’t kill jobs or businesses. In fact, it puts money in peoples’ pockets, which is good news for everyone. The Economic Policy Institute just released a report showing the economic benefits of Congress raising the minimum wage to $17, and it amounts to a $3,100 average annual increase for all American workers currently earning less than $17. As the recent study from economist Michael Reich proved, that money would then circulate through the community, creating even more jobs with the increased consumer demand.

The evidence has become incontrovertible: Raising the wage is good for everyone. Unless you’re actively rooting for wealth to concentrate in the hands of the wealthy few at the top of the economy, there is no good reason in the year 2023 to oppose raising the federal minimum wage.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Workers Keep Fighting for Better Wages and Work Conditions

Just a couple of weeks after delivery drivers negotiated $170,000 annual compensation and benefits packages with UPS management, American Airlines pilots negotiated a compensation increase of 46%.

“American Airlines pilots have approved a new contract that includes more than $9.6 billion in total pay and benefits increases over four years, reflecting the bargaining power held by pilots in an era of airline staff shortages,” reports Reuters.

And this doesn’t just mean bigger paychecks for American pilots—it also means a more humane working environment: “Quality-of-life improvements represent nearly 20% of the increased value of the new contract, the union said. For example, pilots would get premium pay if the company reassigns them from a trip they bid on, or have asked to fly,” writes Reuters.

Meanwhile, in Los Angeles, the WGA and SAG-AFTRA strikes are continuing. David Dayen reports that the Hollywood unions have called on the Biden Administration to investigate the size and power of the major studios, arguing that some antitrust measures might be necessary. FTC Chair Lina Khan has since gone on a major movie industry podcast to argue that the unions have a point, and that the government might look into investigating whether the giant entertainment conglomerates have “broken” the market for movies and television.

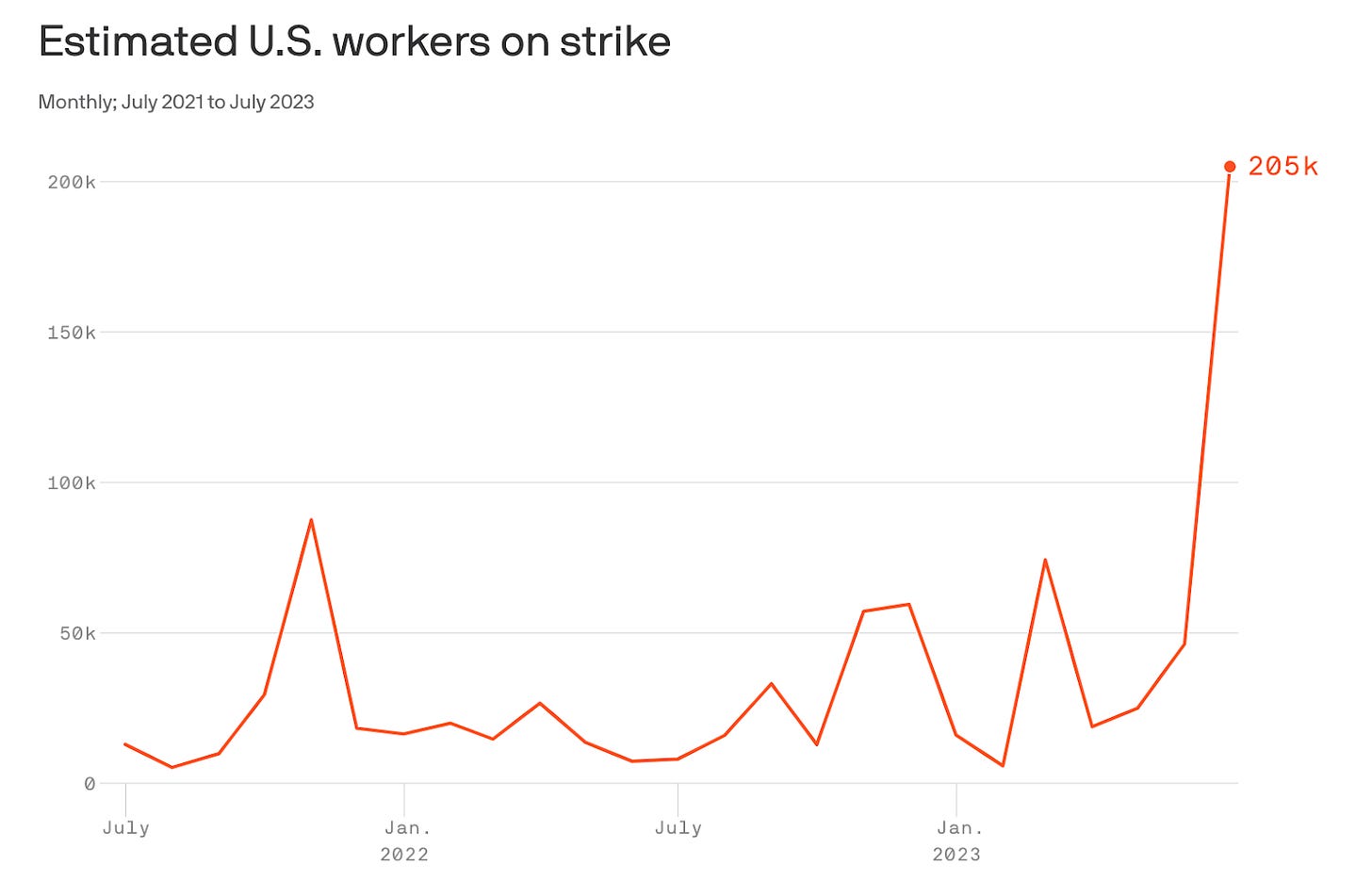

These strikes are leading a new wave of labor activism, reports the New York Times, in which “several prominent unions are now in the hands of outspoken leaders who have taken their membership to the brink of high-stakes labor stoppages — or beyond.” As a result, Axios reports that 205,000 American workers are now engaged in strikes.

That number “could get much larger in the coming months if 146,000 [United Auto Workers] members go out on strike,” Axios notes, adding, “There's also a looming possibility of a strike by 85,000 health care workers employed by California-based Kaiser Permanente — the union representing the system's employees is likely to vote soon on whether or not to authorize a strike.”

As those auto workers continue to bargain with the three biggest automakers in the United States, you should beware of how the media reports on a potential strike. Sarah Lazare reports for the American Prospect that economic consulting firms which are friendly to auto manufacturers are releasing reports claiming to show the economic impact of a strike, and media outlets are credulously repeating their claims that a strike would cost us all billions of dollars. These reports are likely to hurt public support for striking workers and damage their ability to negotiate better wages and benefits for themselves.

Just as media reports that the $15 minimum wage would kill jobs and close businesses were lop-sided in favor of big employers, wealthy employers are using the media to drum up fear that a strike would hurt everyone.

It’s true that strikes cost employers a lot of money. That’s the point of a strike. “Through the collective will to withhold their labor and cost their employers money, workers have not only improved their own lot but won broad social gains, like the eight-hour workday and safer nurse-to-patient staffing ratios,” Lazare explains. “If you believe that employers fail to pay workers for the full value they produce, then you see no moral problem at all with a strike being expensive. And given that the strike is the main tool workers have to improve their conditions, it’s reasonable to believe the social benefits outweigh the immediate hardship and sacrifice required to pull off such a collective action.” Even further, the benefits that workers win from strikes and credible threats of strikes are good for the economy because they shift money away from CEOs and toward workers, boosting the whole economy. Rather than carrying a heavy cost, these wins are an investment in our economy’s future.

In other words, it’s important to wear your media criticism cap when you read about labor actions like this. Consider these three questions:

Do the reporters mindlessly quote from economists and consulting firms without talking to a single worker or union representative?

Do they talk about big scary “hits to the economy” without analyzing where those impacts will fall and who, exactly, will be taking the economic hits?

And do they fail to examine the benefits of worker actions, like the huge raises that were just won by UPS drivers and American Airlines pilots?

If the answer to any of those three questions is “yes,” you’re not reading a news report—you’re reading pro-business propaganda.

The Economic Mainstream Tells the Federal Reserve to Cool It

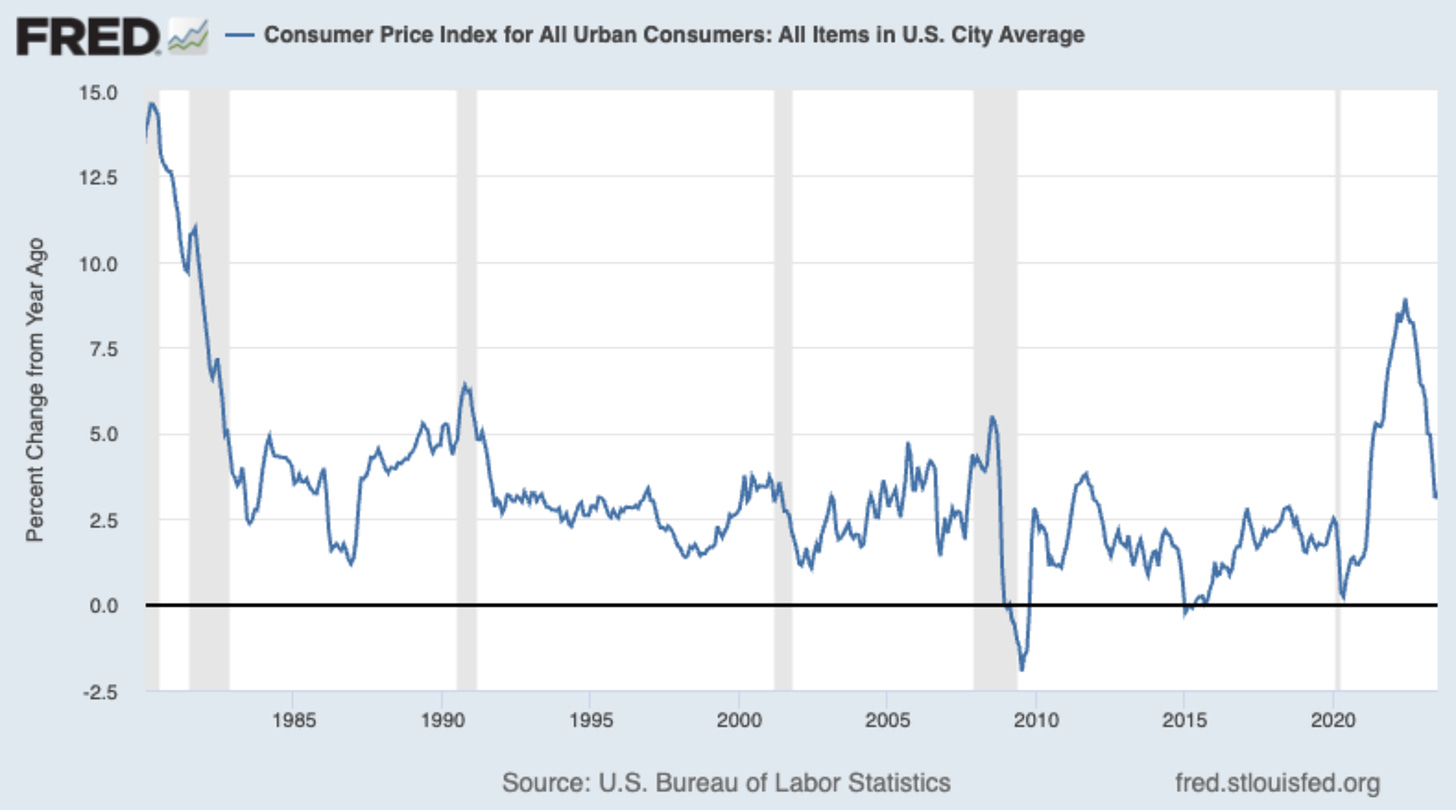

Tomorrow, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell will give a speech that experts will pull apart for signs of his strategy to combat inflation. Powell has been aggressive in his campaign to raise interest rates in his stated goal to lower inflation, even as prices have declined and the labor market has stayed strong.

Over the past week, a number of high-profile economic commentators have come out with pieces questioning the Federal Reserve’s stated intention to get inflation back down to 2%. These pieces are basically pleas aimed directly at the Federal Reserve, urging Powell to stop trying to cool down the economy.

Obama economic czar Jason Furman, who is about as mainstream as economists come these days, wrote in the Wall Street Journal:

If the Fed were adopting an inflation target from scratch, it would likely choose a target above 2%. A higher target inflation rate has costs, especially the time and attention people spend trying to account for how much their current dollars will be worth in a year or 10. But a higher target also has the benefit of helping cushion the economy against severe recessions. When the economy slows, higher inflation means that price hikes and wage freezes can become a less unpalatable alternative to widespread layoffs for business looking to cut costs. Higher inflation also helps the Fed stimulate investment, because any given nominal borrowing cost becomes less onerous when businesses can count on future price increases to meet it.

Paul Krugman amped up his fight against the 2% inflation benchmark in the New York Times: “many economists now believe that the 2 percent target was a mistake, that it should have been 3 or even 4 percent. For what it’s worth, economists of a certain age remember Ronald Reagan’s second term, when inflation averaged around 4 percent, and few thought of it as a terrible problem:”

And Nick Timiraos of the Wall Street Journal doubled-up on the Journal’s push with a newsy examination into the 2% target. He first makes the case that 3% inflation should be considered a victory, and then he examines other ways that the Fed could more slowly reach 2%: “Another camp suggests the central bank could take a lesson from former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan and get to its 2% target more leisurely…Rather than push immediately for 2%, get there gradually over several years by holding rates at a level that could seem slightly higher than they need to be, and letting opportunities, such as the occasional economic slowdown, nudge inflation down bit by bit.”

The Federal Reserve is trying to cool the economy down by raising interest rates, which often comes in the form of job losses. But this time around, the greatest impact the Fed’s interest rate increases seem to be having on the economy is raising the cost of mortgages. The rates on a 30-year fixed mortgage this week soared to a 21-year high, to 7.09%:

Since the Fed is making it so expensive to buy a home, housing prices have stayed high, even as many other prices have slowed down or declined. “In June, sales of existing homes fell nearly 19 percent from the year before,” writes the New York Times’s Gregory Schmidt. Those high mortgage rates are forcing homeowners to stay in homes rather than sell them, and the resulting “scarcity of listings has kept housing prices elevated: The median price of an existing home was $410,200 in June, the second-highest since the organization began tracking the data in 1999, down only marginally from a high of $413,800 a year ago.”

Due to these high prices and unattainable mortgage rates, home sales continued to fall last month. “Sales of existing homes, the majority of purchases, decreased 2.2% in July from the prior month to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 4.07 million,” reported the Wall Street Journal, amounting to “the slowest monthly sales pace since January, and the slowest July pace since 2010.”

So in an effort to lower inflation, the Federal Reserve is raising interest rates. Those interest rates are raising mortgage rates, making it harder for Americans to buy homes. And one of the leading contributors to inflation this year has been…housing costs. This is getting ridiculous.

This Week in Middle Out Policy

Speaking of housing, Rachel M. Cohen at Vox reports that housing construction unions in California have finally managed to overcome their differences with housing attainability activists, and are now “actively supporting the major housing bills winding their way through the [California state] legislature, or otherwise signaling that they’ll no longer fight them.” This alliance officially ends a significant roadblock to progressive housing policy that could help bring down housing costs in our most populous state.

Seems like this should be bigger news: The Department of Justice broke up a giant drug price-fixing company this week. Matt Stoller explains, “Teva Pharmaceuticals and Glenmark Pharmaceuticals unlawfully banded together to increase prices for a widely-used drug that lowers cholesterol and stops heart attacks and strokes. The Antitrust Division’s actions put an end to that conspiracy, forcing Teva and Glenmark to pay over a quarter of a billion dollars and ensuring they can no longer control access to this vital medication.”

Meanwhile, a coalition of authors, publishers, and booksellers, emboldened by recent antitrust actions from the Biden Administration, have called on the Justice Department to “investigate not only Amazon’s size as a bookseller, but also its sway over the book market — especially its ability to promote certain titles on its site and bury others,” reports the New York Times.

As Generation X approaches retirement age, Martha C. White reports that student loan payments have eaten up a significant portion of the funds that otherwise might have gone toward 401K investments. And as student loan payments start up again this fall, White reports that the average Xer with student loans still owes just shy of $50,000—totaling about a quarter of the nation’s entire $1.6 trillion in student loan debt.

Harold Meyerson explains how the state of New Jersey is modeling excellent pro-worker behavior by taking strong action against employers who commit wage theft. The state’s Department of Labor “revealed that 27 of the state’s 30 Boston Market outlets had violated the state’s minimum-wage and kindred laws, and that the company owed more than $600,000 to 314 employees, and having received no response from the company in response to these DOL-verified claims, the DOL issued a stop-work order for those 27 outlets. If an outlet refused to close, the company could be fined $5,000 per day,” he writes. That’s the way to do it—if an employer can’t afford to pay their employees, they can’t stay in business.

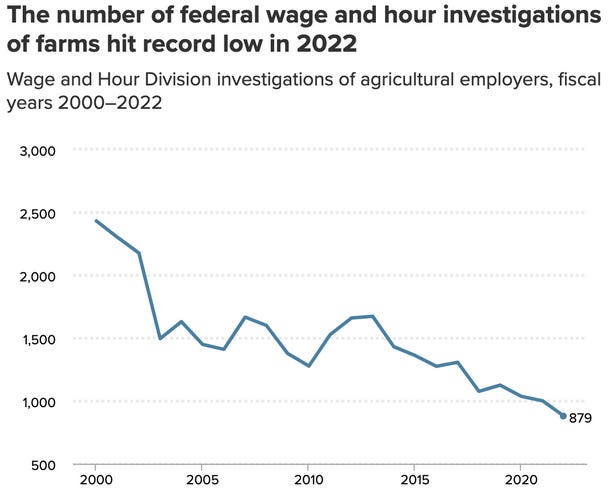

Unfortunately, the federal Department of Labor is falling down when it comes to investigations of wage and time theft in the agricultural industry. Last year, after decades of decline, the DoL hit a record low number of investigations of agricultural employers:

Did you know that the financial industry regulates itself when it comes to investigating and punishing abuses by stockbrokers and securities firms? It’s true—the organization is called the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, and it will probably not surprise you to learn that FINRA has rarely been strict when it comes to enforcing its rules. However, Harold Meyerson explains that a new lawsuit threatens to move FINRA’s authority over to the Securities and Exchange Commission, where it belongs.

Unfortunately, it looks like the SEC’s new rules for private equity have largely been defanged. Axios explains that aside from a new rule requiring PE to “distribute a quarterly financial statement to their investors, including information on fees, and also require annual financial statement audits,” most of the proposed bans on the fees that PE firms use to suck their targets dry have been cut from the rules.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

For most of the 21st century, we’ve allowed Big Tech companies to set the pace of innovation and to establish the rules of how business gets done. These big firms have changed our day-to-day lives, and in return they’ve accrued trillions of dollars in wealth. On the podcast this week, Daron Acemoglu discusses his new book Narrow Corridor, which argues that we’ve allowed a handful of the world’s wealthiest people to enrich and empower themselves with the benefits of their technological innovation, to the detriment of everyone else. Acemoglu is one of our finest economic thinkers, and he’s devoted a lot of his substantial intellect to figuring out a better way to broadly share the benefits of technological innovation.

Closing Thoughts

Yesterday’s Republican presidential debate largely fell outside of the province of what we discuss in this newsletter. I wish we could have had a substantive debate on economic policy, rather than arguments over whether we should invade Mexico or not, but that’s not the world in which we live right now.

But I do want to acknowledge that among leading Republican presidential candidates, there is a growing call to reject the central trickle-down pillars of tax cuts for the rich, deregulation for the powerful, and low wages for everyone else. Perhaps most surprisingly, Vivek Ramaswamy—the youngest Republican presidential candidate, who is running in second or third, depending on which poll you watch—proposed a minimum 59% inheritance tax rate.

Because we live in an age of context collapse, before we get any further I want to clarify that this is not an endorsement of Ramaswamy—in fact, just a few weeks ago, I noted that Ramaswamy’s undemocratic proposal to raise the voting age to 25 represented “an unconscionable step backward in our nation’s history.” And that’s before we get to his even more radical claims that climate change is a hoax, or that we should export the Second Amendment to Taiwan to thwart China. He is out of step with a vast majority of Americans on most issues, and most of his ideas are outright dangerous.

But in the matter of inheritance taxes—and given his unhinged performance in last night’s debate, possibly only in the matter of inheritance taxes—Ramaswamy offers some insight. “The point is that the inheritance tax rate should be very high,” Ramaswamy wrote in his memoir, adding, “We shouldn't allow people to become billionaires just by having rich parents.”

Even ten years ago, this would have been an unthinkable proposal from a Republican presidential candidate—or a leading Democratic presidential candidate, for that matter. This is a sign that income inequality has grown so large that the very trickle-down policies which created that inequality are now unpalatable to a large majority of Americans, and politicians are finally taking notice.

It’s possible that our politics could be in the beginning of an economic policy realignment akin to the one that took place during the Reagan Administration. After both the mainstream Republican and Democratic parties embraced trickle-down economics, the political conversation shifted away from a debate over whether we should cut or raise taxes on the wealthy, and toward haggling over exactly how much the tax cuts for the wealthy should be.

There’s a long way to go yet to see if Bidenomics becomes as integral to the conversation as Reaganomics was, but if we can get to a place where everyone in the mainstream civic conversation agrees that regulations, taxes, and investments are a necessary economic action, I’ll be happy to engage in endless pedantic quibbling over how high the taxes and investments should be.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach