Friends,

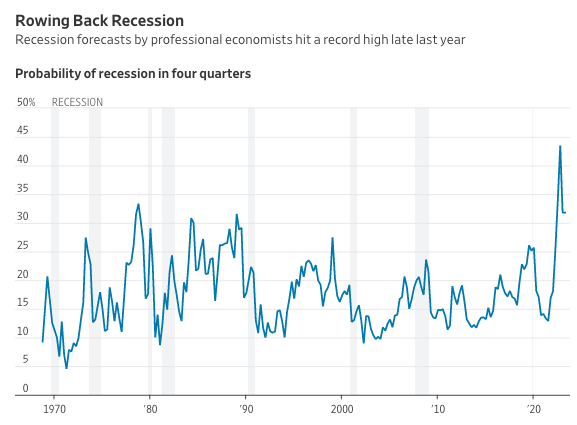

James Mackintosh at the Wall Street Journal asks, “Where’s the Recession We Were Promised?” In the piece, he notes that while economists spent most of last year ringing the alarm bells about an impending recession, their forecasts have dropped off tremendously in the last six months:

As if in answer to the question in Mackintosh’s headline, New York Magazine’s Eric Levitz published an excellent piece titled “The Recession That Didn’t Happen.” Levitz pulls apart one of the primary economic signals that have been used by pundits and economists over the past year and a half to predict an oncoming recession.

He writes, “when Forbes predicted in February that the U.S. economy was poised to rapidly weaken, it based this assessment on ‘a precipitous drop in housing permits.’” Levitz continues, “But this week, new data revealed that both permits and housing starts rebounded sharply in May with the latter posting the biggest monthly gain since 2016.”

Since January of 2022, many of the nation’s highest-profile economic figures have repeatedly predicted a recession around the corner, and when that recession failed to materialize, they simply warned that it was lurking around the next corner. Levitz writes that for a variety of reasons—including rising wages, relatively low household and business debt when compared with early 2008, and many other points that you can read in the full piece—the economy seems fairly sturdy. Then he argues that our leaders should work to maintain the strong jobs numbers and declining inflation numbers that they have, rather than embrace the Fed’s proposal to raise interest rates until millions of people lose their jobs, in a big and risky swing to revert to the pre-pandemic economy.

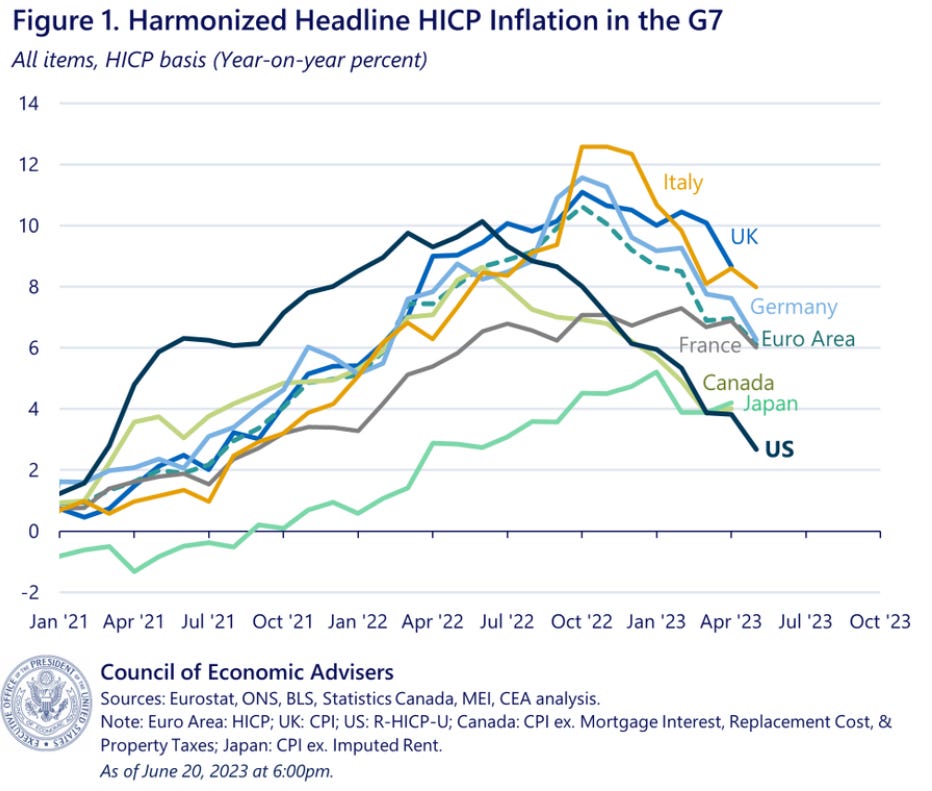

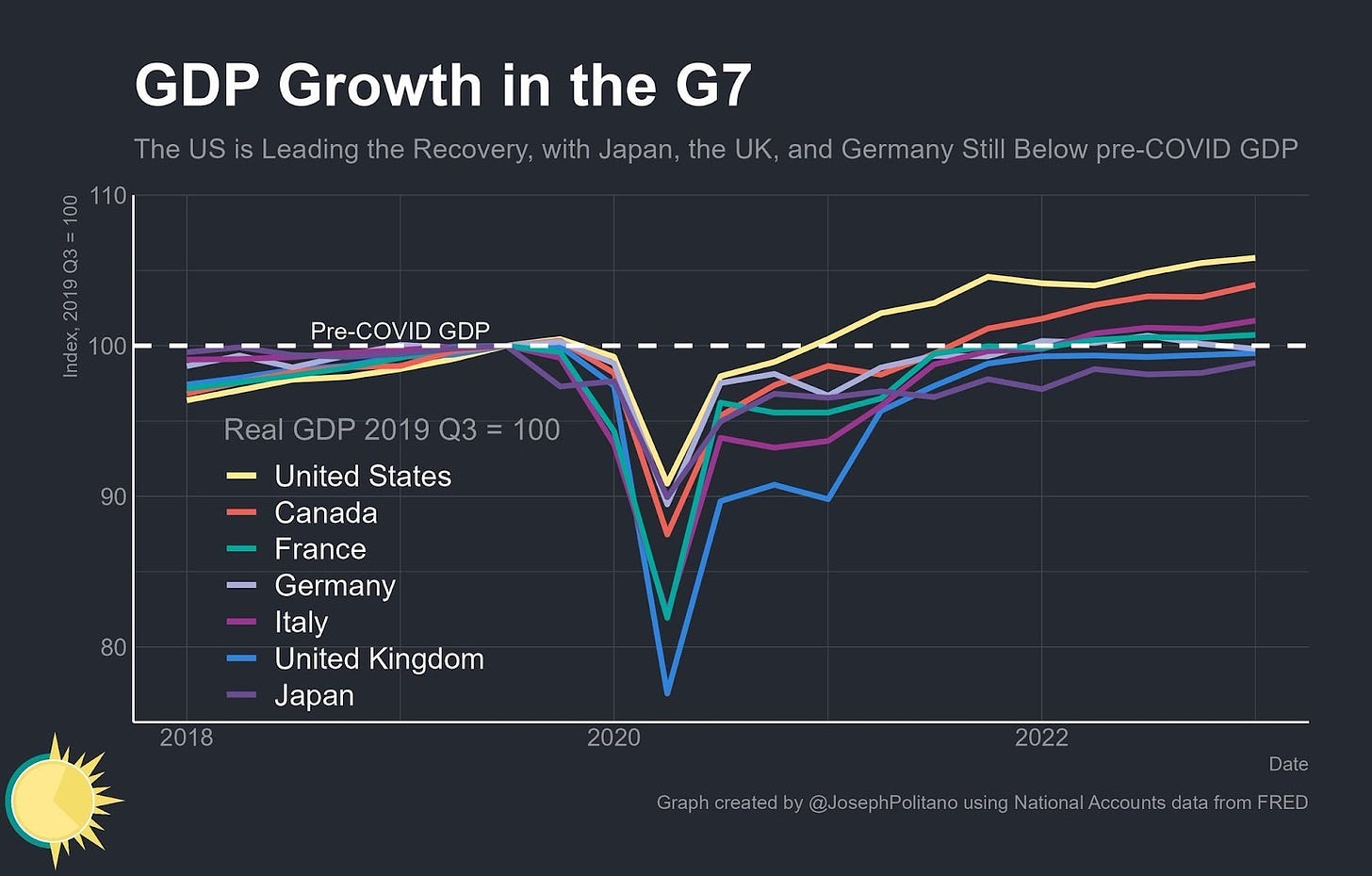

Meanwhile, as journalist Jordan Weissmann notes, “The U.S. has the highest post-pandemic growth among the G7, and it currently has the lowest inflation (both headline and core).”

Even the shaky economic signals we received earlier this year are improving as more data comes in. This morning, the Commerce Department announced that its previous Gross Domestic Product estimates for the first quarter of this year, which reported GDP growth of 1.1% over Q1 last year, were revised up to 2 percent. The GDP had to be adjusted because the consumption rate of ordinary Americans was higher than expected, by nearly half a percentage point. In short, consumer spending continues to power our nation’s economic growth.

This is all good news, of course, but as we’ll discuss in this week’s newsletter, many Americans don’t feel like they’re economically in great shape, and those concerns are valid. Prices are still up over where they were before the pandemic, wages were flat for forty years before their recent increases, and housing in many parts of the nation has become unaffordable for middle-class families. There’s still much more work to be done, but the signs at least indicate that the work is heading in the right direction.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Rolling Out “Bidenomics”

Following last week’s rip-roaring debut of a campaign speech, in which President Biden focused on the strong economy that his policies have built, Biden yesterday rolled out an even stronger speech touting his economic record.

In the buildup to this week’s speech, the media repeatedly pointed out that Biden’s polling on the economy is weak. The Wall Street Journal’s Ken Thomas and Annie Linskey write that one “recent poll by Quinnipiac University showed 41% [of registered voters] approved and 55% disapproved of Biden’s handling of the economy, though those figures showed improvement since earlier in the spring.”

Of course, in this hyper-politicized age, it’s likely impossible for any president to earn sky-high marks on the economy, or most any other issue. Just from eyeballing recent polling, it seems that something like 33% of all Republicans will automatically give low marks to any Democratic president, and probably 25% of all Democrats will refuse to praise any Republican president’s performance. But there’s a lot of room for Biden to grow, and that requires him to tirelessly get the word out about our robust shift away from trickle-down and toward middle-out economics through campaign speeches and ads.

In his speeches, Biden frames the excellent employment rate, wage growth, lowering inflation rates, small business creation stats, green economy and infrastructure investments, and other strong economic signals as clear markers that his economic plans are working. And now he’s calling his economic framework “Bidenomics,” an embrace of a term that conservatives frequently used to deride the economy in 2021, before the president successfully passed three major pieces of legislation to help spur economic growth.

At this point, it becomes necessary for us to clarify the terms we’re working with in this newsletter. “Bidenomics” quite obviously shares many—probably even most—of the same economic principles of what we refer to in this newsletter as “middle-out economics.” This White House brief on “Bidenomics,” for example, is packed with middle-out language:

“ …the best way to grow the economy is from the middle out and the bottom up.”

“...the benefits of a growing economy are only broadly shared when policies are designed to promote and empower workers.”

“...targeted public investment can attract more private sector investment, rather than crowd it out”

“...for markets to function—and for workers and consumers to benefit—our economy requires healthy competition across sectors.”

“...[the pre-pandemic economy was] rooted in a failed trickle-down theory that supported slashing taxes for the wealthy and big corporations, shrinking public investment in critical priorities like infrastructure and education, and failing to safeguard market competition.”

This is all great stuff, and perfectly in line with middle-out economic thinking. But for the purposes of this newsletter, we’ll continue to use “middle-out economics” to describe the economic school of thought that counters the failed trickle-down economics, which prioritized the wealthy few at the expense of everyone else for the last four decades. “Bidenomics” shares most of its DNA with middle-out economics, but it’s likely the two philosophies will differ on some points, and in order to keep that distinction clear, we’ll only use “Bidenomics” going forward to refer specifically to the term as used by the president and other campaign surrogates.

But whatever you call it, the economy is now stronger by most metrics than it was before the pandemic—with the notable exception of prices, which are nonetheless declining from recent highs. This economic push by Biden (and, hopefully, his friends in the Democratic Party) will not only celebrate those gains and make the distinction between a middle-out economy and a trickle-down economy, but it will also make it easier for the media to talk about the economy as a robust, growing force and not a tenuous, fragile thing continually teetering on the edge of a recession.

Six Months Later, Railroad Workers Get Their Sick Days

Late last year, after big railroad corporations refused to negotiate with their workers and railroad employee unions were on the edge of a strike, Congress moved to impose a settlement between workers and their employers to avoid repercussions that could have crushed America’s supply chains and brought the economy to its knees. At the time, many progressives framed the Biden Administration’s decision to urge Congress to end the détente as a failure to support working Americans.

Last week, the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers issued a follow-up to the story in the form of a press release. This development deserves much more attention than it’s gotten, so I’m going to republish the first few paragraphs of the story here:

After months of negotiations, the IBEW’s Railroad members at four of the largest U.S. freight carriers finally have what they’ve long sought but that many working people take for granted: paid sick days.

This is a big deal, said Railroad Department Director Al Russo, because the paid-sick-days issue, which nearly caused a nationwide shutdown of freight rail just before Christmas, had consistently been rejected by the carriers. It was not part of last December’s congressionally implemented update of the national collective bargaining agreement between the freight lines and the IBEW and 11 other railroad-related unions.

“We’re thankful that the Biden administration played the long game on sick days and stuck with us for months after Congress imposed our updated national agreement,” Russo said. “Without making a big show of it, Joe Biden and members of his administration in the Transportation and Labor departments have been working continuously to get guaranteed paid sick days for all railroad workers.

“We know that many of our members weren’t happy with our original agreement,” Russo said, “but through it all, we had faith that our friends in the White House and Congress would keep up the pressure on our railroad employers to get us the sick day benefits we deserve. Until we negotiated these new individual agreements with these carriers, an IBEW member who called out sick was not compensated.”

And it’s not just IBEW workers who have sick days—most of the railroad unions, across the big national carriers, have now negotiated paid sick days for their workers. The Biden Administration continued to push for paid sick leave for these railroad workers long after the media stopped paying attention to this story. They should use this success on behalf of railroad workers to kick off a larger nationwide push for paid sick leave for all American workers, so nobody ever has to choose between getting medical assistance and losing their job.

Meet the New “R”

Earlier in this newsletter, we talked about the panicked cries of economists warning of recession, and how those cries have died down. MarketWatch notes that “Neil Dutta, head of economics at Renaissance Macro Research, fired off a note saying ‘the statute of limitations [on recession predictions] has now kicked in. There are several reasons to be upbeat on the U.S. economy. The recession clock has been reset.’”

Now, another perception of the economy is starting to take shape: A story of resilience. Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times writes that despite the Federal Reserve’s insistent efforts to make it harder for people and businesses to borrow money in order to slow the economy down, house prices and home construction have recently risen.

“The question is whether the economy can slow sufficiently when real estate is stabilizing or even heating back up, leaving homebuilders feeling more optimistic, construction companies hiring workers and homeowners feeling the mental boost that comes with climbing home equity,” Smialek writes. (Smialek’s assertion that the economy needs to slow down and enter a recession is untrue, but she’s just the messenger, here—she’s repeating the Fed’s wrong-headed understanding of how the economy works right now.)

The day after Smialek’s report, the Case-Shiller National Home Price Index found that in April home prices fell by .2% year-over-year, the first annual decline since 2012. But experts don’t seem rattled by that downturn. For one thing, the index reflects a three-month moving average and the market was considerably cooler in January than it is now. The Wall Street Journal talked with Craig Lazzarra, the managing director at S&P Dow Jones Indices, who told the paper that “The U.S. housing market continued to strengthen in April. Home prices peaked in June 2022, declined until January 2023, and then began to recover.”

Meanwhile, renters are seeing some relief in prices that have sharply increased over the past few years. “Rent prices fell 0.5 percent in May compared with the year before,” Rachel Siegel writes in the Washington Post. “The firm’s tracking showed that to be the first year-over-year drop since early in the pandemic, when strong consumer demand collided with a lack of available apartments and homes.” And natural gas prices, which spiked when Russia invaded Ukraine, are now about half what they were at this time last year.

In other words, all the disasters predicted by economists for the past year have failed to materialize. The Wall Street Journal investigated why the near-global push to raise interest rates hasn’t tanked the world’s economy. Their findings include the fact that “government spending has continued to bolster growth, cushioning economic shocks that proved less catastrophic than expected.”

This is a stunning recognition of the success of middle-out economics. Rather than the slow and swampy economic recovery that dragged out from the Great Recession of 2009 through basically the beginning of the pandemic, the recovery from the pandemic recession has been swift and sturdy. The reason for that striking difference is that the pandemic-era economic recovery centered ordinary people with direct cash assistance and government investments in local economies, but after the Great Recession’s banking collapse, our economic policy prioritized the wealthiest people and corporations. When you direct your recovery to grow the economy from the bottom up and the middle out, you get much better results than the trickle-down option.

Greedflation’s European Vacation

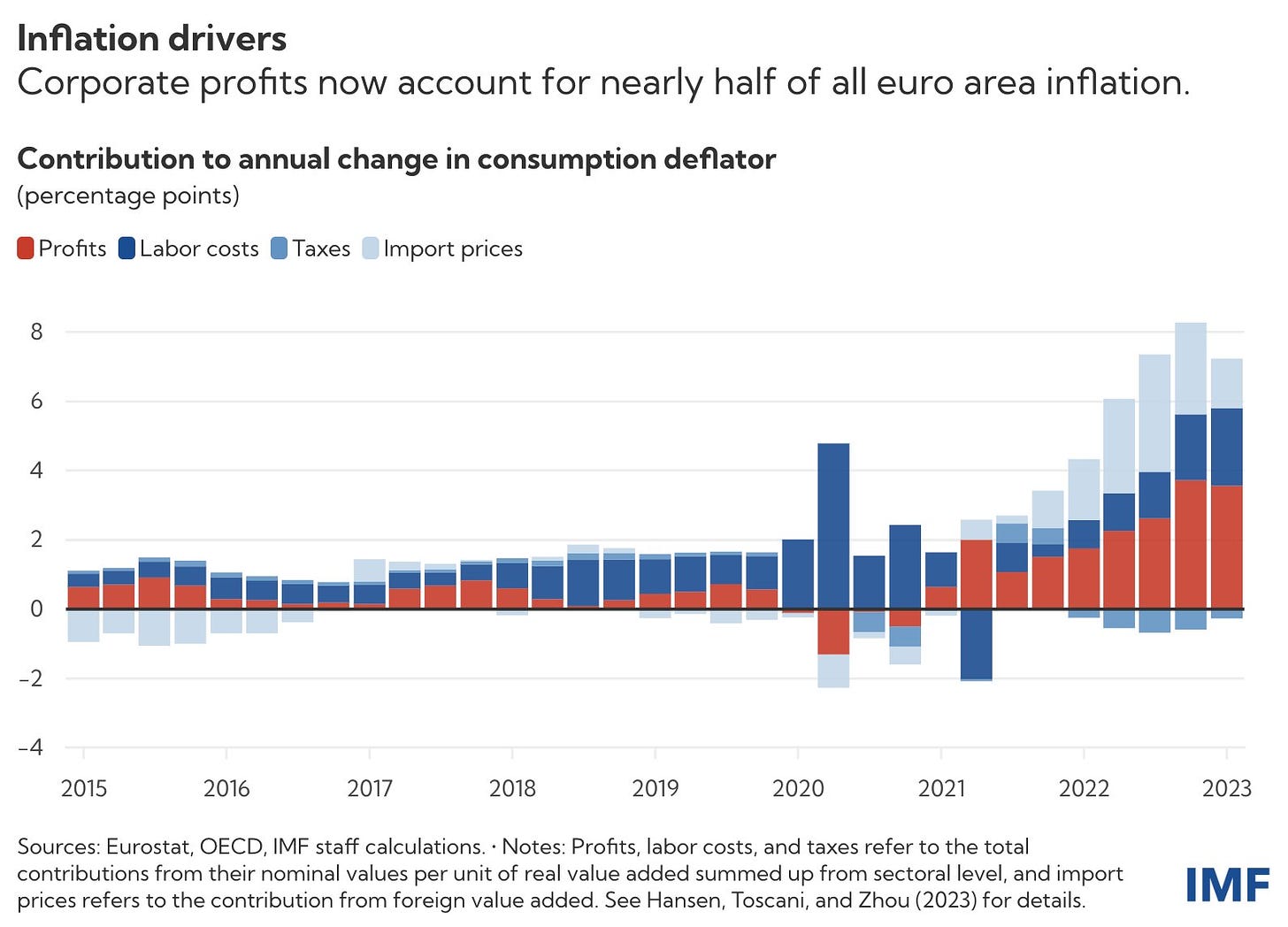

Now if only we could do something about those stubborn price increases that are fattening corporate profit margins. It seems that greedflation isn’t a solely American problem. A new report from the International Monetary Fund finds that “Rising corporate profits account for almost half the increase in Europe’s inflation over the past two years as companies increased prices by more than spiking costs of imported energy.”

So as we’ve been saying in this newsletter for the better part of two years, corporations took advantage of price increases caused by pandemic-era supply chain disruptions to jack up their own prices and pocket the extra profits. This report offers mainstream confirmation that greedflation is real, and that it’s a problem, at the very least, throughout the northern hemisphere—if not the whole world.

So what can we do about this? The IMF report, frustratingly, doesn’t offer any policy solutions. “Now that workers are pushing for pay rises to recoup lost purchasing power,” the report continues, “companies may have to accept a smaller profit share if inflation is to remain on track to reach the European Central Bank’s 2-percent target in 2025, as projected in our most recent World Economic Outlook.”

I’m not sure that relying on corporations to rein in their own profits out of the goodness of their own hearts is such a compelling economic strategy. Some economists argue that corporations will lower prices when consumers turn their backs on higher-priced products, and we have seen a little bit of that in the U.S. But many corporations are more than happy to serve a dwindling customer base that is willing to pay inflated prices.

I wrote about my concerns around mass-market corporations behaving like luxury brands a couple of weeks ago, so I won’t repeat myself here. Because most of modern Europe has traditionally been friendlier to regulations, hopefully, some European leaders are looking at price-to-profit ratio controls along the lines of what France has been doing to lower grocery prices. If greedflation continues as it has, our leaders will have to reinvestigate the hands-off relationship between corporations and governments that evolved during the trickle-down era.

This Week in Middle-Out Policies

The American Prospect profiles Katherine Tai, the Biden Administration’s trade representative. Tai has become an outspoken critic of America’s past trade policies, which she says “created an incentive for countries to compete by maintaining lower standards, or by lowering their standards even further, as companies sought to minimize costs in pursuit of maximizing efficiency. This is the race to the bottom, where exploitation is rewarded and high standards are abandoned.”

On Monday, President Biden announced “more than $42 billion in new federal funding to expand high-speed internet access nationwide, commencing the largest-ever campaign to help an estimated 8.5 million families and small businesses finally take advantage of modern-day connectivity.”

Axios did a dive into the Biden Administration’s continuing war on junk fees, which tend to exploit low-income families through mechanisms like annual percentage rates on credit cards, outrageous ticket fees, and “buy now, pay later” schemes.

American policymakers should pay close attention to our neighbor to the north. Canada recently passed a program that drives the cost of daycare down to as little as $10 per day, from highs of as much as $60 per day. According to the New York Times, the Canadian government “plans to spend up to 30 billion Canadian dollars to create a total of 250,000 new low-cost child care spaces, mostly in nonprofit or public day care centers and family-based providers.”

And finally, Senators Elizabeth Warren and Sherrod Brown have launched a formal inquiry into the exploitative practice of employers handing out bogus “manager’ titles to low-wage employees in order to force them to work overtime for no extra pay. Lauren Kaori Gurley at the Washington Post writes that the Senators asked two dozen companies “including Burger King, Subway, Pizza Hut, Arby’s, H&R Block and Life Time Fitness — that were identified by the [National Bureau of Economic Research] report as having the highest share of ‘overtime avoiding positions’” to provide internal data about employment, hours worked, and titles. That hearing will be one to watch very closely. To learn more about this practice of exploiting managerial titles in the meantime, I recommend listening to this Pitchfork Economics conversation with journalist Marcus Baram about America’s painfully outdated overtime laws.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

On this week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics, Paul and Goldy discuss their economic-themed summer reading lists. If you’re ordering books from your local independent bookstore or library to take on vacation, this episode is a must-listen. With categories ranging from sci-fi to politics to history, I’m positive that there’s a recommendation that will suit every kind of summer reader in this list.

Closing Thoughts

I wanted to call your attention to a new law in a Delaware city that blurs the line between economics and politics. CBS News’s Irina Ivanova reports that “Seaford, a town of about 8,000 on the Nanticoke River, amended its charter in April to allow businesses — including LLCs, corporations, trusts or partnerships — the right to vote in local elections.”

Thanks to the Citizens United decision that declared money to be valid political speech, corporations already have an outsized amount of power in US elections. But this law actually bestows the right to vote—a right which was denied to women and to Black Americans for much of our nation’s history—to businesses.

Perhaps the most darkly funny part of this story is the justification for giving corporations the right to vote, according to CBS: “Legislators have cast the change as a fix for low turnout in municipal elections.” The irony here is that many Seafordians presumably don’t vote because they feel as though their votes don’t matter—and much of that powerlessness comes from the perception that politicians are unduly influenced by wealthy corporations. Giving corporations the vote simply removes the middleman from the process.

Seaford’s proposed new voting laws mark the latest data point in the nationwide trend of politicians making it harder for people to vote, and making it harder for existing votes to count. Republican presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy has proposed raising the voting age from 18 to 25, for instance, which would take the right to vote away from more than 30 million Americans—an unconscionable step backward in our nation’s history.

In democracy, as in economics, inclusion is the key to a growing and healthy system. When more people participate in government by voting, our system is stronger and more representative of the will of the people of the United States—which is the whole point of a democracy in the first place.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach