Which Came First—the Price Increases or the Eggs?

The Pitch: Economic Update for January 26th, 2023

Friends,

Wisconsin, where I grew up, is a state that takes its breakfasts seriously. Every kid is taught practically from birth that you need a hearty meal in your belly before you can pull up the ski pants and face those frigid winter mornings. To this day I love eggs in pretty much all their forms—over easy, soft-boiled, in an omelet with cheese please.

You can tell from the headlines this month that many Americans share this lifelong fondness for traditional breakfast foods, because everyone is freaking out over the skyrocketing price of eggs. Across the US, the price of a dozen eggs has more than doubled over the last year, from $1.78 to $4.25.

But that’s only the national average—in certain parts of the country, a dozen eggs will set you back nearly ten bucks, if you’re lucky enough to find eggs in stock at your local grocery store at all.

The mainstream media has largely reported that this spike in egg prices is due to an avian flu outbreak in 2022 that resulted in tens of millions of chickens being slaughtered to prevent the strain from spreading even further. But Roshan Abraham at Vice spotlights a new report that argues the price increases have a different cause.

Farm Action, a political action group that seeks to “create a food and agriculture system that works for everyone, not just a handful of powerful corporations,” recently sent an open letter to FTC Chair Lina Khan arguing that at its worst point last year, the avian flu epidemic only shrank the supply of eggs by six percent. In fact, Farm Action argues, “With total flock size substantially unaffected by the avian flu and lay rates between one and four percent higher than the average rate observed between 2017 and 2021, the industry’s quarterly egg production experienced no substantial decline in 2022 compared to 2021.”

Instead, Farm Action points to the same brand of corporate greed that has artificially raised prices throughout the economy for the last year. “The real culprit behind this 138 percent hike in the price of a carton of eggs appears to be a collusive scheme among industry leaders,” Farm Action writes, “to turn inflationary conditions and an avian flu outbreak into an opportunity to extract egregious profits reaching as high as 40 percent.”

Specifically, Farm Action blames a mega-conglomerate called Cal-Maine, which is responsible for 20 percent of the nation’s egg production. They note that the company’s gross profits skyrocketed throughout the past year, “going from nearly $92 million in the quarter ending on February 26, 2022, to approximately $195 million in the quarter ending on May 28, 2022, to more than $217 million in the quarter ending on August 27, 2022, to just under $318 million in the quarter ending on November 26, 2022.”

Any expert will tell you that this kind of quarterly profit escalation doesn’t just happen in the course of doing business. There would have to be some huge disruption—being bought or sold, a huge lucky windfall, or some kind of chicanery—to cause that kind of extraordinary profit over the course of a year. And as we saw with the corporate greed that inspired more than half of last year’s price increases, when one corporation gets a taste of the ballooning profits to be raked in from price-gouging, other businesses in the same industry are quick to follow.

Unlike the avian flu excuse that so many media outlets repeated earlier in the month, corporate greed is not an act of God. It’s a specific choice made by powerful people, and our leaders have policies and regulations in place to punish people who make intentional choices that harm other people. It’s time for our leaders to step up and take action.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

As the economy improves, all eyes turn to the Fed

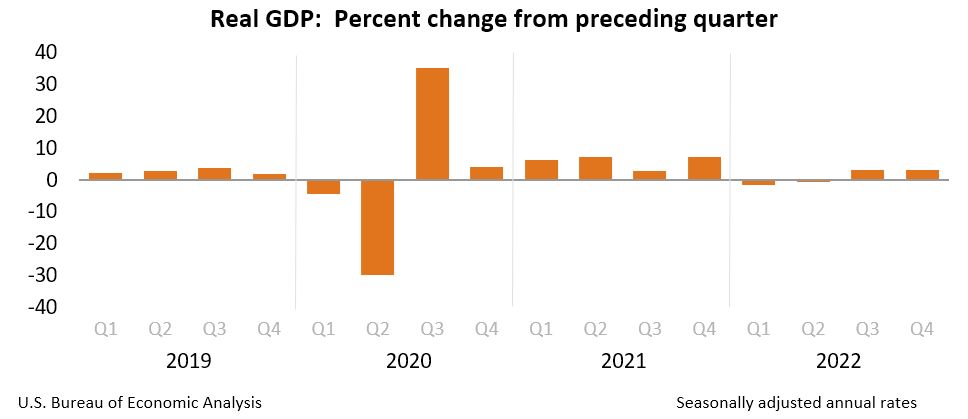

This morning, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that the Gross Domestic Product increased by a solid 2.9% in the fourth quarter of 2022, nearly matching the GDP’s 3.2% increase in the quarter before. Though the media is trying its best to find a downside, this report signals that the economy, despite the stubborn pronouncements of many pundits, is still not plunging into a recession.

The GDP report is only the latest in a string of good economic news, particularly surrounding inflation. “People across the country are finally experiencing some relief from what had been a relentless rise in living costs,” writes the New York Times’s Jeanna Smialek. “After repeated false dawns in 2021 and early 2022 — when price increases slowed only to accelerate again — signs that inflation is genuinely turning a corner have begun to accumulate.”

This is great news, though of course prices are still elevated. And Smialek says there’s little consensus about what inflation will do next: “Some economists expect inflation to remain stubbornly faster than before the pandemic, while others anticipate a steep deceleration. Some anticipate something in between.”

No matter which of those paths unfold, the most important factor that economists will be watching over the next year are employment numbers. It doesn’t matter if prices decrease if people aren’t employed. Right now, the labor market is still very strong, though down from the highs of the last few years. And the signals for the long-term health of the job market are generally positive, but there are some mixed signals in certain places.

For one thing, employers are cutting temp workers, which is often a sign that higher unemployment rates are on the way. But that just could be because larger employers in general are cooling down their hiring and, in the case of the tech and media sectors, laying off workers. American small businesses, which hire fewer temps than large corporations, are currently hiring at robust rates.

And while we have seen a trend of high-profile layoffs among the biggest tech companies, the fact is those job cuts are currently sticking to the tech sector, which overhired during the pandemic. These layoffs aren’t as devastating as, say, a Rust Belt factory closure because tech workers are still in high demand: recent studies show that nearly 80 percent of these laid-off workers find new employment within three months.

In the meantime, workers paid at the bottom of the income scale—especially Black workers and young workers—have seen the biggest gains recently. If these trends continue, with highly employable workers at the high end of the wage scale temporarily losing their jobs at big firms while small businesses continue to hire traditionally low-wage workers for bigger paychecks in a competitive labor market, that would be good news for the whole economy.

The Federal Reserve could hurt the labor market by continuing its aggressive series of rate hikes when it reconvenes at the end of January. Rachel Siegel reports for the Washington Post that members of the Fed are publicly debating over the next interest-rate hike: Should it be a modest quarter-point, or a more aggressive half-point? That difference might not seem like much, but the signal the Fed sends early next month could either calm or incite the recessionary panic that’s pervading Wall Street and CEO corner offices.

In any case, the damage may already be done. A new working paper from the Federal Reserve warns that interest-rate hikes are exacerbating income inequality by making it harder for lower-income Americans to buy homes. Bloomberg’s Tracy Alloway reports:

…a tightening of monetary policy which increases mortgage rates by 1 percentage point reduces the share of home purchase loans going to low- and moderate-income borrowers by 2.1 percentage points (or 7.5%) in the weeks following the announcement. First-time home buyers are even more affected, with a 1 percentage-point tightening causing a 4 percentage-point fall in the share of loans going to low- and moderate-income households.

Given that so much personal and generational wealth in America is tied up in home ownership, those single-digit drops could have exponential consequences on would-be homeowners’ retirement funds and their childrens’ educational outcomes.

So a lot is riding on this next interest-rate decision. The best writing I’ve seen on the Fed’s choice comes from Mike Konczal and Justin Bloesch at the Roosevelt Institute. “With measures of labor demand cooling and key sectors catching up in supply, the Fed has a choice: They can allow for a wait-and-see period that lets a soft landing materialize, or they can insist that unemployment must go up to crush inflation, introducing the risk of a serious recession,” they write.

Bloesch and Konczal point out that the labor market is already cooling from its highs of 2021 and 2022, but it’s cooling in a way that’s not leaving hundreds of thousands of workers jobless, which is the ideal outcome for a healthy recovery from inflation. In fact, employment numbers have remained remarkably stable in fields that matter most for the economy’s recovery—including in manufacturing and, especially, construction:

“In part, these booms [in employment] reflect real structural shifts in the economy, including demand for more space for working from home, as well as re-shoring and domestic investment in manufacturing capacity,” Konczal and Bloesch write. In other words, the fundamentals of the economy have shifted because of the pandemic, but those fundamentals are lively enough to hold the labor market aloft.

The authors project that “it’s possible that all of the labor market cooling happens on the churn and wages side, and almost none on the layoffs side.” While we want to see paychecks grow, it would be better for those wage increases to temporarily slow down across the spectrum rather than to see widespread job losses across the economy. Better a “soft landing” with lower inflation and slower wage growth than the “soft landing” that some experts are calling for, with layoffs in every sector and “mildly” inflated unemployment numbers.

A middle-out case against monopoly

I urge you to read David Dayen’s latest piece for the American Prospect, which lays out all the work the Biden Administration has undertaken to rein in corporate power and rewrite the rules to encourage competition in the marketplace and discourage monopolies and other abuses of corporate power. The piece is perhaps the best explanation I’ve yet to see of the middle-out argument for regulation as an important component of healthy market capitalism, and it phrases the Biden Administration’s goal as a return to the Progressive and New Deal eras: “Breaking up monopolies was a priority then, complemented by numerous other initiatives—smarter military procurement, common-carrier requirements, banking regulations, public options—that centered competition as a counterweight to the industrial leviathan,” Dayen explains.

Dayen included many examples of how the Biden Administration has promoted competition, and more examples are popping up every day. Case in point: The Justice Department is leading a new lawsuit against Google’s online ad monopoly, which, if successful, would break up the company into several businesses, separating its search division from its advertising division, for example.

Trickle-downers might argue that this is unnecessary interference with business, but the truth is that if the DoJ’s suit is successful, it would divide one mega-business into several smaller, but still wildly successful, businesses, and it would increase competition in a field that is being choked to death by a handful of large players. Only someone who never uses the internet could honestly argue that internet advertising is a perfect and enjoyable experience for consumers. Breaking up online advertising would create more jobs, inspire creativity and innovation in the space, and improve outcomes for customers.

Additionally, the Biden Administration is also apparently gearing up to combat the proposed Albertsons-Kroger merger, which would kill competition in markets from coast to coast and drive up prices while also driving down worker wages. Julie Creswell at the New York Times says the merger will not likely face a final decision until at least this time next year, and nobody expects the merger to go unmodified at a federal level.

And this week, executives at Live Nation went to the Senate for a hearing on their ticketing monopoly. After the Obama Administration’s Department of Justice approved the Ticketmaster-Live Nation merger in 2010, the event behemoth now controls more than 70 percent of the ticketing and live event market in the United States. Anyone who’s ever had to buy tickets for an event through Ticketmaster understands the downside of a monopoly: the experience is frustrating, the prices are ridiculously high, and the customer service is nonexistent.

Thanks in part to ticked-off Taylor Swift fans, though, the Department of Justice might try to correct its previous error by suing Live Nation, in the hopes that a judge might order the organization to break itself into two distinct companies–one for events hosting and one for ticketing. After decades of our leaders accepting virtually every corporate merger uncontested, this kind of pro-competitive outcome suddenly doesn’t seem so far-fetched.

This week in economic policy

The Biden Administration continues to roll out new policies to help improve the economy broadly for Americans. Here are three announcements from the past week that you might have missed:

Lydia DiPillis writes that the Biden Administration is “creating a system for assessing the worth of healthy ecosystems to humanity. The results could inform governmental decisions like which industries to support, which natural resources to preserve and which regulations to pass.” In other words, the government will be able to quantify and put a price tag on the positive impacts of ecological preservation. This is important because traditionally we’ve only been able to measure the economics of environmental impact by the literal price of environmental damage. Putting a positive economic value on environmental stewardship frames the preservation debate in a whole new way.

Rachel Siegel reports on the Administration’s baby steps toward getting unsustainably high rents under control, including “a ‘Blueprint for a Renters Bill of Rights’ that, while not binding, sets clear guidelines to help renters stay in affordable housing” and “the ‘Resident-Centered Housing Challenge,’ that aims to get housing providers as well as state and local governments to strengthen policies in their own markets.”

And just in time for tax season, the Internal Revenue Service is “rolling out new automated systems and staffing up its brick-and-mortar taxpayer assistance centers.” Additionally, the IRS is racing to make sure its 5000 new agents are trained in customer service. After the Biden Administration invested $80 billion in the agency to catch wealthy tax cheats, the IRS is under pressure to be more responsive this year than it has been in the recent past.

Labor is poised for a comeback—but first, policies have to change

The Economic Policy Institute released a report calculating the economic cost of worker misclassification, putting a price tag on employers who classify full-time workers as “independent contractors” in order to avoid paying benefits.

“For example, a typical construction worker, as an independent contractor, would lose out on as much as $16,729 per year in income and job benefits compared with what they would have earned as an employee,” EPI reports. Additionally, “A typical home health aide, as an independent contractor, would lose out on as much as $9,529 per year in income and job benefits compared with what they would have earned as an employee.”

But this is about more than just employers nickel-and-diming employees out of thousands of dollars a year by misclassifying them. These employers are also essentially diminishing these independent contractors’ contributions to all the investments that hourly and salaried workers make with every paycheck. Contractors pay some Social Security and Medicare at a lower rate than their higher-paid non-contractor peers, for example, and they don’t contribute at all to workers’ comp insurance.

For every independent contractor employed by construction companies, for instance, EPI estimates “a decline in social insurance revenues between $1,781 and $2,964” per worker per year. For truckers who are misclassified as independent contractors, it’s roughly $3000 a year. For security guards, about $1100 is robbed from social insurance plans by employers misclassifying their workers.

Of course, one way to discourage this kind of economically extractive behavior is to unionize the workforce. Another new study from EPI shows that America added 200,000 unionized workers last year, and that union election petitions increased by 53% over the year before, showing that more Americans than ever are interested in unionizing their workplace. But because so many people returned to work last year, the percentage of unionized workers in America actually declined by .3 percentage points, to an abysmal 11.3% of the American workforce.

The report offers a fascinating snapshot of unionization in the American workforce, including which industries saw declines in unionization rates (local government, real estate and rental and leasing, transportation and warehousing) and which industries saw increases in unionization last year (durable goods manufacturing; arts, entertainment, and recreation; and agriculture and related industries.)

But the fact that so many American workers want to organize but are unable to signifies that our policy environment favors employers over workers. If we want to see more workplaces successfully unionize, we have to create policies that allow workers to organize. This Niskanen Center policy package offers seven different perspectives on how we can encourage more unionization in the American workplace, from fostering the manufacturing industry to passing the PRO Act to reforming unemployment.

The will to reform the employer/employee contract is clearly there in the American workforce. But unions and worker power have been under constant attack from leaders from both parties over the past 40 years. Simply wanting change won’t turn the clock back—it will take considerable effort from our leaders to reform the workplace in America. But the good news is that America’s desire to unionize and take back that power is only growing in popularity with each passing year. Leaders who make it easier to organize will tap into that groundswell of support.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

This week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics marks the 10th anniversary of the Fight for $15 with two policy experts from the National Employment Law Project. They discuss a new report showing that raising the minimum wage has not just increased paychecks for millions of workers—it’s also increased union participation and helped to shrink the racial wealth gap.

On Civic Action Live this week, we’ll discuss the real story behind the skyrocketing price of eggs, the fight against outsized corporate power, and the positive signs for many American workers even as wealthy tech workers are laid off. Join us at 10:30 am PT tomorrow.

Closing Thoughts

We don’t usually traffic in Washington DC gossip around these parts, but a report from Tyler Pager, Jeff Stein, and Rachel Siegel at the Washington Post yesterday caught my attention. The authors write, “President Biden is close to naming the next head of the National Economic Council, the top economic position in the White House, and Federal Reserve Vice Chair Lael Brainard has emerged as a top contender.”

Regular readers of The Pitch will likely recognize Brainard’s name: She’s the first Federal Reserve official to publicly recognize that corporate price-gouging played a significant role in the higher inflationary prices of the past year. Brainard is still, I believe, the highest-ranking Fed official to make this case, and she doubled down on her claims in a speech last week, in which she announced that “Retail markups in a number of sectors have seen material increases in what could be described as a price–price spiral, whereby final prices have risen by more than the increases in input prices.”

That sounds pretty tame—it’s just a fancy way to say corporations are pocketing a good share of those higher prices—but it’s the equivalent of a grenade tossed into the conventional wisdom. Remember, when we started talking about greedflation a year ago, experts decried the claim as outrageous. So for a Federal Reserve official to step forward and acknowledge the truth behind inflationary prices, at a time when her peers were still describing inflation in antiquated 1970s terms, demonstrates both a meaningful understanding of how the economy really works and personal bravery at a time when most careerists would choose to stay silent.

I don’t know about you, but those are qualities that I’d like to see in my National Economic Council head. Additionally, Brainard has called for more oversight of Wall Street, sought economic solutions that would incentivize environmentally sound outcomes over reckless pollution, and promoted policies that would end systemic racism in our banking system. In other words, she would be the first middle-out NEC head, and she could make a huge difference in updating the nation’s economic policy so it works for everyone, not just the wealthy few at the top.

These kinds of rumors about open positions often serve as a trial balloon to gauge public response, and the Post’s story is based on three high-level officials. Let’s hope this one turns out to be true, because it could be the most consequential staffing decision President Biden could make in the second half of his first term.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach