Friends,

The past two days delivered a wide array of monthly inflation numbers, and while the news is much better than it was earlier this year, you’d be hard-pressed to characterize any of the numbers as good. Due to a complex wave of pressures including supply chain snags and corporate price-gouging, prices have risen much higher than the recent increases in wages that American workers have seen in the past year. To dust off a word that was overused throughout the pandemic, it’s an unprecedented situation—and as we’ll see momentarily, all these mixed signals are twisting up the economics field into a bizarre knot.

The Producer Price Index, which measures the costs that manufacturers and distributors pay before items reach consumers, rose by .4% in September. Core prices, which measures prices without the volatile food and energy prices included, climbed by .3% and services prices rose by .4%. These numbers are way down from the highs of March and June of this year, but they’re still on the rise, which suggests that American consumers continue to pay more for food, goods, energy, and services than they have in recent memory. Worse yet, average American wage growth shrank slightly last month, marking the first such decline in a year.

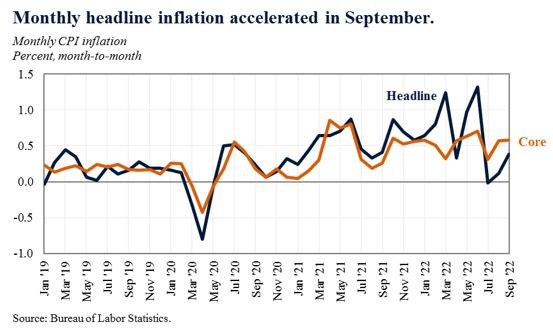

And today’s monthly inflation report came in higher than expected. “Overall inflation climbed 0.4 percent in September, much more than last month’s 0.1 percent reading. The core index climbed 0.6 percent, matching a big gain in the prior month,” writes Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times. Energy prices were down last month, but food prices stayed high and rents were way up.

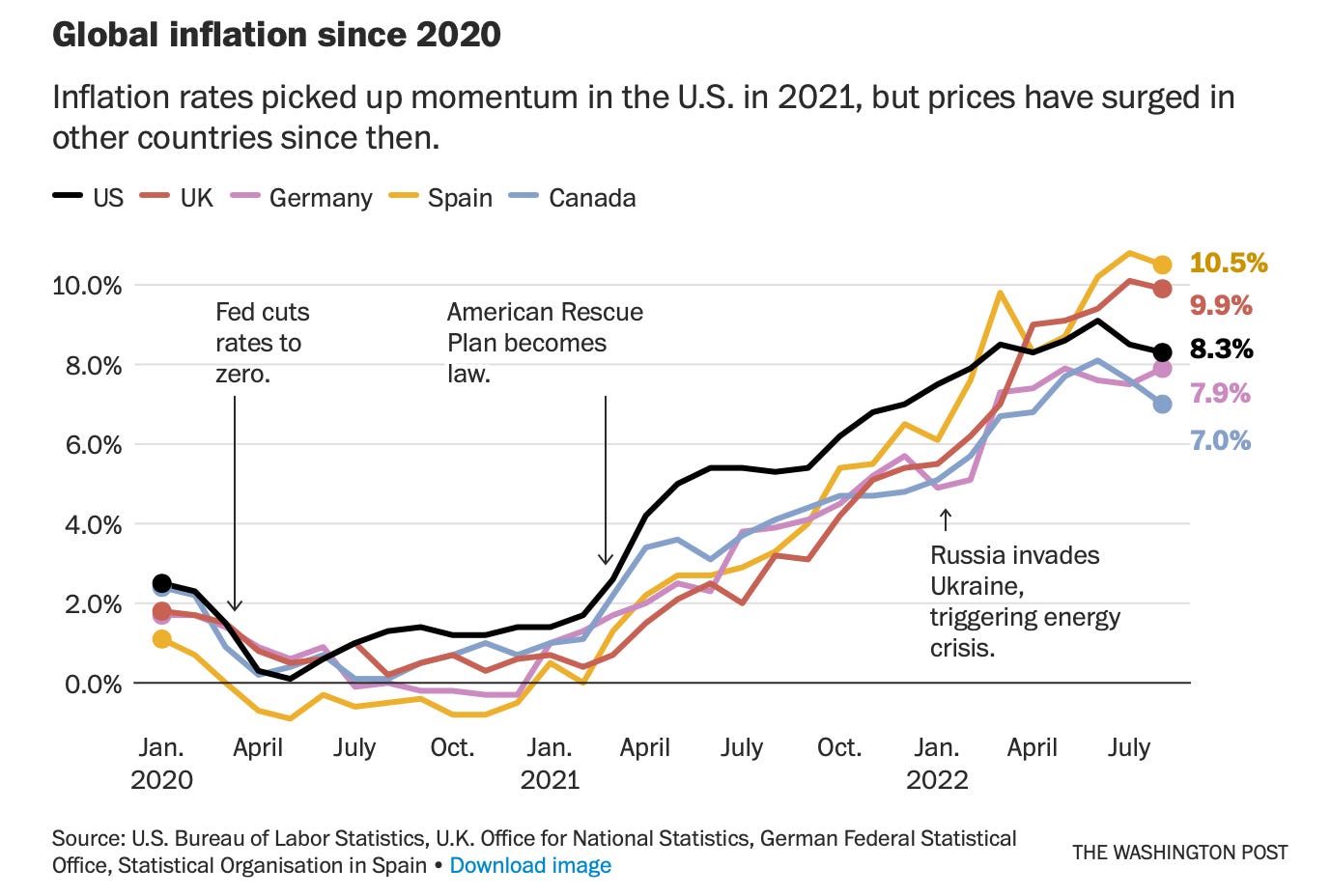

To be clear, inflation is a global problem right now, so it’s not the result of any one nation’s decisions—and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

When faced with this widespread problem, the economics profession and its attendant pundit class seems to have completely lost its bearings. Economics has now become a bizarro world where up is down, bad is good, and the status quo is cheerleading for widespread economic immiseration.

The headlines are positively Orwellian. “The cure for inflation is on the way,” blares a headline from Rick Newman at Yahoo Business. That cure? A recession which will throw millions of Americans out of work indefinitely. When it comes to the stock market, “Good news is bad news again,” warned the Wall Street Journal and Bloomberg.

“Bad news equals good news, good news equals bad news,” Vincent Reinhart, Dreyfus-Mellon’s chief economist, said when the jobs report last week came in stronger than expected. And in my own back yard, the Seattle Times tut-tutted that “Job openings in [Washington state] grew rapidly this summer. That’s not good news.” To be clear, the economists at the center of these stories are twisting themselves up in knots to describe the creation of jobs and increased wages for American workers as bad news.

I can’t believe I have to write this, but good news is good news and bad news is bad news. A good jobs report isn’t a disaster for the economy—it means that more Americans are drawing regular paychecks, and that they’re spending that money in their local economy. Massive layoffs aren’t good news—they’re disruptive events that wipe out financial stability for ordinary Americans, potentially setting back life goals like home-buying or child-rearing by years.

The fact that economists can go on cable news channels and cheerlead the Federal Reserve’s attempts to drive the economy into a recession is yet another sign that the mainstream field of economics has detached from reality. Economics isn't some purely academic exercise where you shuffle numbers around a whiteboard, or a game where you root for Team Massive Unemployment to whip Team Inflation. It’s the story of who gets what, and why. If economists can’t imagine any way to address inflation without immiserating millions of people, it’s way past time for a new understanding of economics to take hold.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

What Will the Fed Do Next?

Given that inflation is still rising, it’s hard to make the case that the Federal Reserve’s ongoing plan to increase interest rates is actually helping. The Fed has two more meetings scheduled for this year, on November 1st and 2nd, and December 13th and 14th. Members have signaled that they will raise interest rates at one or, likely, both of these meetings. A CNN report from yesterday even characterized the Fed as being “obsessed” with inflation, to the point of being blind to every other economic indicator.

Just so we’re all on the same page, the Fed is raising interest rates to make it more expensive for businesses and people to borrow money. The intent is to slow the economy down and decrease consumer demand by making it harder to build and expand businesses, or to invest in new projects, or to hire workers. When the Fed did this in the early 1980s after years of sustained high inflation, millions of Americans lost work and inflation did come down. So now the Fed is betting everything that the exact same gambit will work again—even though this inflation crisis has completely different causes than the 1970s inflation crisis. It’s a 1981 solution for a 2022 problem.

But with the red-hot labor market showing a few signs of cooling, this is the Federal Reserve’s choice right now: They can continue to doggedly raise interest rates even further in hopes of eventually killing inflation, or they can wait and see what effects their previous rate hikes will have on the economy.

If they continue to raise rates, millions of people will lose their jobs. As economist Claudia Sahm told the Financial Times, “Inflation is a hardship, especially for those living paycheck to paycheck, but no paycheck is a disaster for families.”

It’s a great point. So far as I’m aware no polling organization has tested this question, but I’m fairly certain that a majority of Americans would gladly choose to pay more at grocery stores over a sustained period of time over losing their jobs in a sustained wave of unemployment.

The biggest problem with the Fed’s action is that nobody can prove raising rates will bring inflation down. Outside of the Federal Reserve, most people seem to understand that this wave of inflation isn’t being caused by widespread consumer demand. And even inside the Fed, clear voices of dissent are ringing out. Lael Brainard, the Vice Chair of the New York Federal Reserve, opened a speech this week with a statement of fact that runs contrary to the Fed’s conventional wisdom: “Inflation is high in the United States and around the world reflecting the lingering imbalance between robust demand and constrained supply caused by the pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine,“ she announced in the second sentence of the speech.

That might sound like boring economist phrasing, but it’s actually a bit of a bombshell. Brainard is making it clear that your increased wages aren’t the main cause of this inflationary wave. And since widespread consumer demand didn’t cause this inflation, it’s not clear that killing widespread consumer demand will do anything to lower prices.

When considering what’s at stake, I keep thinking of this quote from Eric Levitz’s conversation with economist and historian Adam Tooze:

I have to say, as a father of a young person who’s about to graduate college, who went through the total disruption of her life through COVID, if you think about the fate of that entire cohort of young people and we’re talking hundreds of millions of people around the world whose education was disrupted by COVID lockdowns and who are now exiting education into a labor market that might be disrupted by a post-COVID recession - I think there’s a very strong case for running the global economy hot. There’s a matter of intergenerational justice.

Now, obviously, there are cost-of-living concerns too. But for young people, the crucial thing is to get a foothold in the labor market and not to fall into an unemployment track. Because we know that a big shock to the labor market has an enduring, almost lifelong effect on people’s careers.

To gig or not to gig?

This week, the Labor Department issued a new proposal that could reverse a Trump Administration move to classify thousands of employees as independent contractors. Vox’s Rachel M. Cohen explains that if the Biden Administration’s rule takes effect, workers who have been misclassified as contractors would then be subject to the same labor regulations that govern employees at traditional firms like a minimum wage, paid time off, taxes and Social Security withheld from paychecks, and other benefits.

If the proposal is adopted, the Biden Administration would roll back a Trump-era broadening of independent contractor laws. Experts predict that if the proposal is adopted into law, and if it then survives the inevitable legal challenge from business interest groups—a big “if,” to be sure—employers like Lyft could have a two-tier system of workers, with occasional drivers who pick up a shift or two on the weekends operating as contractors and more frequent drivers who put in more than 20 hours per week counted as traditional employees.

The alarming return of child labor

For The American Prospect, Sarah Lazare investigates a shadowy political action group that’s lobbying to repeal child labor laws in states around the nation. The National Federation of Independent Business has pushed conservative state representatives in New Jersey, Wisconsin, and Ohio to promote legislation that allows employers to schedule teenagers for longer hours on school nights and even longer hours during weeks in which school isn’t in session.

Lazare explains how businesses are trying to promote these bills as wholesome character-building endeavors—teaching kids about responsibility, saving teens from the terrors of too much screen time—and lawmakers are selling them as a solution to the tight labor market for employers.

“The summer of 2021 saw the highest level of teen employment since 2008, at a rate of 32 percent,” Lazare notes, adding that many fast food restaurants are aggressively recruiting 14- and 15-year-olds at reduced pay.

Of course, relaxing child labor laws is really about power. It’s supplying service industry employers with a new stock of desperate workers who are unlikely to know their rights and who need to help their impoverished families make ends meet at a time when Congress allowed the Child Tax Credit to lapse. And if exploitative low-wage employers are able to access a continually replenished pool of young workers, they won’t have to match the rising wages that their peers in the service economy have had to pay over the last year and a half.

This week’s good numbers

The National League of Cities issued a report this week finding that American cities are enjoying a fiscally strong 2022 after two years of pandemic uncertainty. Specifically, they report that “nearly 9 out of 10 finance officers surveyed by NLC expressed optimism in their ability to meet fiscal needs in their current fiscal year 2022.”

City finance officers cited several reasons for their optimism: “a strong rebound of city revenue sources such as income and sales taxes, two years after the start of the COVID-19 outbreak in 2020, coupled with a once-in-a-generation and timely injection of federal monies in the form of American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).”

In yet another convincing argument against applying narrow restrictions to financial support, the NLC says that the flexibility of ARPA funds was key to their success, allowing each city to devote funds to their biggest problems. For instance, Axios reports, Billings, MT updated its 911 system while other cities addressed housing instability, and still others devoted ARPA funds to helping small businesses get through the second year of the pandemic.

Next year, Social Security payments will increase by the biggest cost of living adjustment in four decades—an average monthly increase of $140, or an 8.7% increase over last year. At the same time, thanks in part to the Inflation Reduction Act, Medicare premiums will decrease for the first time in over a decade, meaning that seniors will have additional spending power next year—even taking inflation into account.

And Rose Khattar and Lauren Hoffman report at Ms. that the gender wage gap narrowed by one penny last year for women working full-time, and by four cents for all women in the workforce. (Though it should not go ignored that Black and Latina women workers still fare considerably worse than their white counterparts.) Hoffman and Khattar suggest that next year’s gender wage gap could narrow even further. For one thing, women’s wage growth has outpaced men this year:

And for another thing, they write that “recent Biden administration and congressional policy reforms, including the Inflation Reduction Act and the student loan relief plan, will no doubt alleviate some of the financial pressures women are facing and bolster their economic security in the long run.”

After decades of these numbers pointing in the wrong direction, it’s heartening to see gains for seniors and women—and to know that several of the policies enacted this year will help guide those numbers in the right direction for the next few years to come.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

On Civic Action Live, we’ll discuss this week’s inflation numbers, what the Federal Reserve should do next, and why good news is good, actually. Join us on Friday morning at 10:30 am PST.

The Pitchfork Economics podcast this week features a wide-ranging, wildly entertaining conversation with economist Mark Blyth. They discuss UK PM Liz Truss’s attempt to revive trickle-down economics, how corporations and the wealthy have offloaded economic uncertainty onto the poorest share of the population, and why it’s important to move fast to combat climate change.

Closing Thoughts

With less than a month before the midterm elections, it’s important to note that two states and the District of Columbia have minimum wages on the ballot this year.

Voters in Washington DC are considering Initiative 82, which would phase out the tipped minimum wage for service economy workers. Currently, DC restaurant and bar owners are only obligated to pay a $5.35 minimum wage for employees if their tips elevate them above the District’s $16.10 hourly minimum wage. If Initiative 82 passes, employers of tipped workers would be responsible for paying the full minimum wage by 2027.

This is a no-brainer for DC voters. Despite the trickle-down claims of restaurant owners who argue that they’ll be forced to close or fire workers if they have to pay the full minimum wage, a number of states including California, Alaska, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington, phased out tipped minimum wages years ago with no impact to the local restaurant industries. DC voters already overwhelmingly voted to kill the tipped wage in 2018, but their city council, embarrassingly, overturned the will of the people under pressure from industry lobbyists.

Nebraska voters are considering raising the statewide minimum wage from $9 per hour to $15 by 2026, and tie the wage to cost of living thereafter. The National Employment Law Project points out that raising the minimum wage will benefit Nebraska employers by reducing turnover, increasing productivity, and creating more jobs by increasing customer demand. An estimated 150,000 Nebraska workers would see a wage increase if voters approve it this November, and NELP estimates that their average “annual earnings would increase by $2,100, which amounts to over $278 million in additional earnings for all affected workers.” That’s a lot of additional consumer spending.

Voters in Nevada are considering a different kind of minimum wage initiative: a measure which would increase the state’s minimum wage from $9.50 an hour to $12 per hour by July 2024, but which would strip the inflation adjustments that are currently written into state law. If Nevada voters approve the measure, the state’s minimum wage would stay at $12 until another increase is approved at some point in the future.

This would be a huge mistake for Nevada. Cost of living increases have become an essential feature of minimum-wage legislation, ensuring that no workers are left behind. Here in Washington state, workers on January 1st next year will see the minimum wage increase by a little over 8.5% simply to keep up with increased costs of necessities like food and housing. Put another way, if there was no inflation adjustment written into Washington state’s law, our minimum-wage workers would effectively be losing 8.5% of the value of their wages in January of next year. This is not a minimum wage increase–it’s simply an adjustment to ensure that workers stay whole. (And because higher minimum wages create a ripple effect that raises the wage for workers who earn slightly more than the minimum wage, many thousands of additional workers will likely see an inflation adjustment at the same time.)

When the midterm results start coming in on November 8th, all eyes will turn to a few high-profile races near the top of the ticket in several states. But in many ways, these minimum wage initiatives might reveal more of America’s true feelings about the economy, inflation, and the source of true prosperity. I’ll be keeping a close eye on these results for that reason.

Be kind. Be brave. Get vaccinated—and don’t forget your booster.

Zach