Friends,

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve announced that it was raising interest rates by another three quarters of a percent, making it more costly to borrow money in the hopes of slowing the economy down and curbing inflation.

Even though the New York Fed recently acknowledged that many of the high inflationary prices Americans are paying are due to the “greedflation” of corporate price-gouging, and not the economy running hot, Fed Chair Jerome Powell was resolute in his insistence to cool the economy down. “We will keep at it until we are confident the job is done,” Powell announced.

The majority of Fed board members signaled that the Fed would be likely to raise interest rates by another three-quarters of a point and another half-point by the time the year is over. Interest rates are now higher than they’ve been since the Great Recession.

So what does this mean for you? Victoria Greene, chief investment officer at G Squared Private Wealth, said in an email that “Powell seems determined to tame inflation [and is] willing to sacrifice some of the job market for it”

About the “sacrifice” that Powell is happy to make on behalf of you and other working Americans: The Fed now predicts that unemployment will climb to 4.4% next year. If that prediction is accurate—a big “if”—that means an additional 1.25 million Americans will lose their jobs over the course of the next year. Powell said in a press conference that he considered that tick up in unemployment to be “relatively modest,” adding that “the labor market continues to be out of balance”—which is certainly an interesting way to say that we have very low unemployment and high wages.

Part of the problem is that, as Joseph Politano writes in his excellent Apricitas Economics newsletter, the economy is so strange right now that the Federal Reserve perceived good news (like a strong labor market) to be bad and bad news (like the possibility of a recession) to be good. When your compass interprets north as south and south as north, you’re almost certainly heading in the wrong direction.

This issue of The Pitch is devoted largely to the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates, what it means for the average American, and what our leaders could be doing to combat inflation instead. If you take away only one lesson from this issue, though, I hope it’s this: Our leaders can’t afford to blindly trust the Fed to do the right thing to combat high inflationary prices right now.

The Federal Reserve performs an important duty in the American economy, but its members are fallible—specifically, they’re susceptible to the same trickle-down thinking that captured mainstream economic thinking for the past four decades. More experts and elected officials should be publicly engaging with the Fed’s campaign to raise unemployment and kick off a recession, in order to inspire a meaningful public conversation about our economic direction.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

What the Fed’s decision means for workers

Virtually everyone agrees now that if the Fed succeeds in its mission to raise interest rates and slow down the economy, we will have a recession, and more than one million people—possibly many millions—will lose their jobs. Robert Pollin at The Nation doesn’t mince words on the Fed’s recent push to drive up interest rates: He calls it an “attack on American workers,” and he ties it directly to the 40-year trickle-down campaign to keep the wages of ordinary American workers stagnant.

“The Fed’s current policy amounts to embracing the principle that US workers cannot be allowed to gain enough bargaining strength to push up wages and reverse 40 years of rising inequality,” Pollin writes. (And even the Wall Street Journal agrees that the bigger paychecks Americans have been taking home over the past year are not the cause of skyrocketing prices.)

Dean Baker at the Center for Economic and Policy Research makes a compelling case that, contrary to the Fed’s campaign to raise unemployment, workers don’t have to be punished in order for inflation to go down. His proposals, including several different routes to shrink CEO pay, cracking down on monopolies, and getting a handle on corporate corruption, would lower costs for all Americans without putting over a million Americans out of work. Pollin, for what it’s worth, agrees—and he also cites green-energy policies like energy-efficient buildings and transportation as another way to bring down high fuel prices.

Also for the Nation, Mike Konczal explains that workers in America are on better economic footing than elsewhere in the world, including much of Europe. Despite sharing similar inflation rates with much of Europe, American unemployment is lower and our economy is stronger. Why is that? Because Europe’s leaders invested in business during the pandemic, while America invested directly in workers:

First, since unemployment insurance was increased by a set amount, those at the bottom of the income distribution scale benefited the most, reducing income inequality. With so many people applying for new jobs, there was additional churn and circulation that let people upgrade their skills and find better work. This meant that employers had to compete to get and train workers and offer better working conditions. Without this choice to support workers rather than businesses, it’s impossible to imagine the rapid wage growth and the increased union activity that we’ve been seeing.

So policies that centered ordinary Americans created this relatively strong economy. Perhaps continuing to invest in the middle and working class, not putting them out of work, would help the economy grow through this moment of international turbulence?

How the Fed’s decision is affecting housing

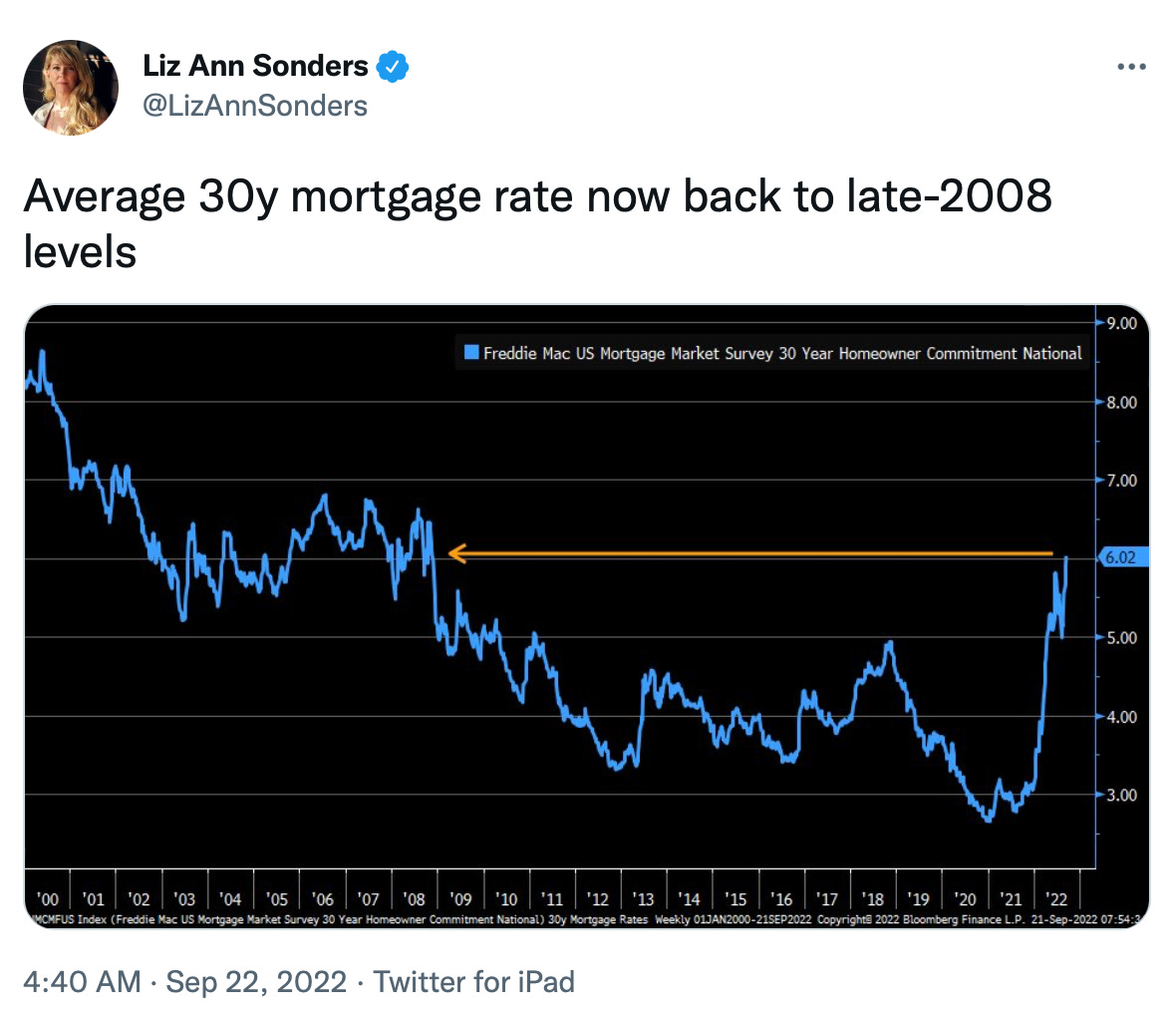

Of course, raising interest rates isn’t a direct tie to employment. The Fed raising rates makes it harder for businesses to get affordable loans, which slows growth, which eventually causes declines in employment. The housing sector, though, tends to respond directly to the Fed’s interest rate hikes or dips—when rates go down more people take out mortgages, and when rates go up fewer people can afford mortgages.

In fact, the average 30-year mortgage rate is now near what it was at the height of the housing crash:

So how is the housing market overall? Currently, it’s seen its seventh straight monthly decline. Additionally, new reports this week confirmed that “confidence among single-family homebuilders eroded for a ninth consecutive month in September, while permits for future homebuilding tumbled to the lowest level since June 2020 in August,” reports Lucia Mutikani at Reuters.

But because the housing market is tight, and because everyone needs shelter, housing prices are still very high—and they are declining at a very slow rate. “The median existing-house price increased 7.7% from a year earlier to $389,500 in August,” Reuters notes. And Redfin reports that asking rental prices spiked 11 percent in August, which is unfortunately the slowest growth rents have seen in a year.

So the housing market is simultaneously in decline and still way too expensive for many Americans to afford. Unless we see construction numbers start to climb, the market will continue to be pinched for many months—likely, years—to come. The free market simply isn’t likely to create enough supply to meet the demand. Considering that most American cities are seeing unhoused populations boom, federal and local governments should probably step in and invest in construction and housing for working Americans.

How the Fed’s decision affects the rest of the world

Robert Kuttner at The American Prospect explains how the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates has inspired their European counterparts to do the same. But because Europe’s job market is much weaker than America’s, their economy is slowing down much faster and sharper than ours.

This could create a vicious cycle—a negative feedback loop that pushes the world economy into a deep hole. If it continues like this, Jay Hatfield at Infrastructure Capital Advisers told Marketplace his firm predicts that “the U.S. stays out of a major recession, but the rest of the world, except China, does go into a significant recession.” And of course because the American dollar has so much global power, poor and developing countries will bear the brunt of the recession as prices climb out of the reach of millions worldwide.

Germany, which continues to be the strongest economy in Europe and one of the strongest economies in the world, is taking steps to address rising prices through robust government investment. This week, German officials announced that they were nationalizing the German gas company Uniper in order to protect energy resources and (presumably) keep costs lower for German citizens this winter.

One expert in international policy told the Washington Post that this move was the first big leap into a coming trend of “really heavy state intervention into energy markets.”

“In some cases, it’s bailing out politically sensitive or economically vital companies like Uniper and others it’s redesigning markets, price caps, interventions and to a capacity prices. So this is not the end,” he told the Post. It doesn’t take an economics whiz to predict that we’re going to see more nations embrace strategies like this, which were unthinkable back in the neoliberal salad days of the trickle-down 1990s.

What we could do instead

Max Zahn at ABC News admits what many economists are afraid to acknowledge: “the rate hikes have failed to significantly reduce prices” thus far, he writes. One economist Zahn interviewed characterized the Fed’s rate increases as “a mess,” adding “There should've been a debate before launching into interest rates. There should've been a discussion between political leaders and the public.”

Zahn takes the opportunity to interview economists about alternate measures for bringing down prices, including price controls, a tax on windfall corporate profits, and ramping up American production.

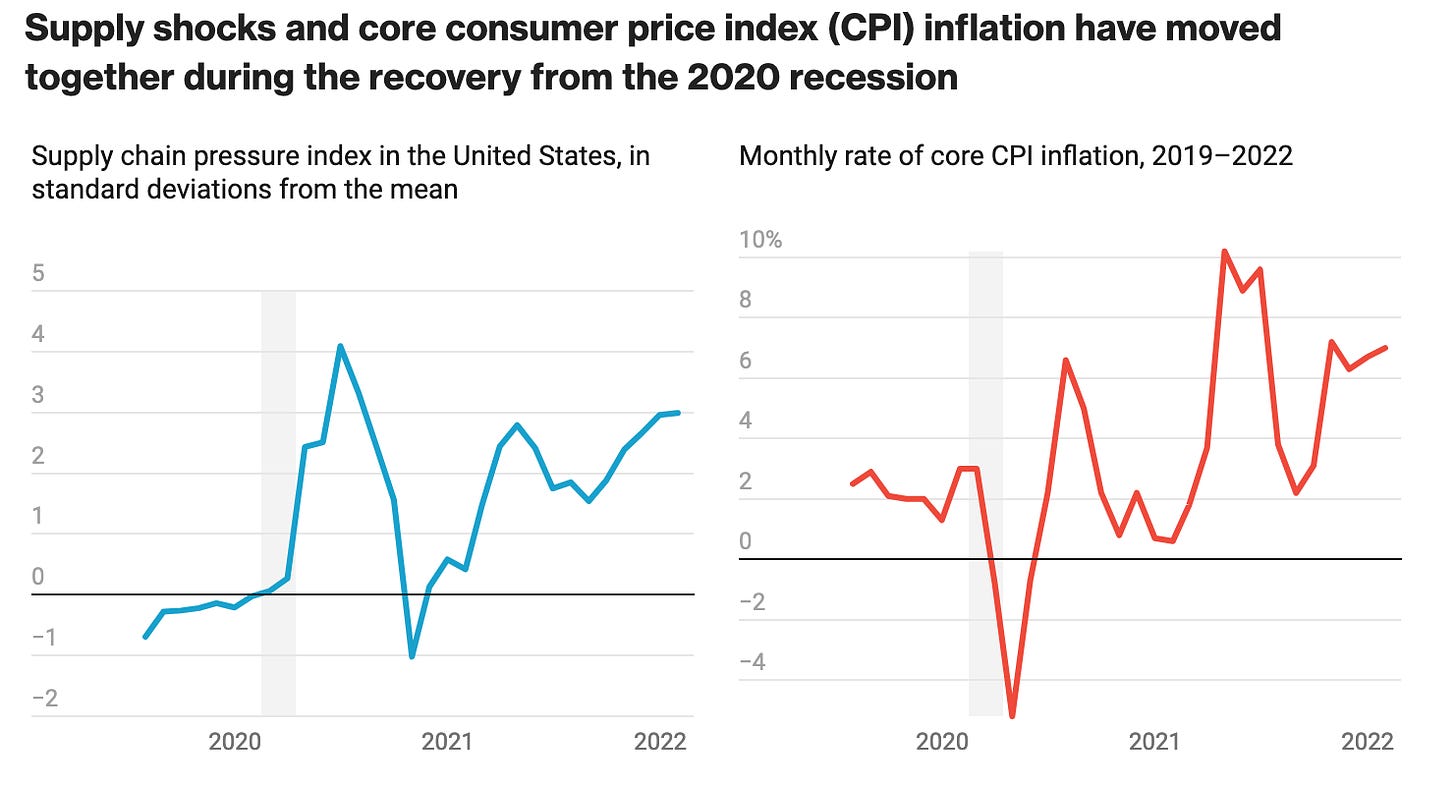

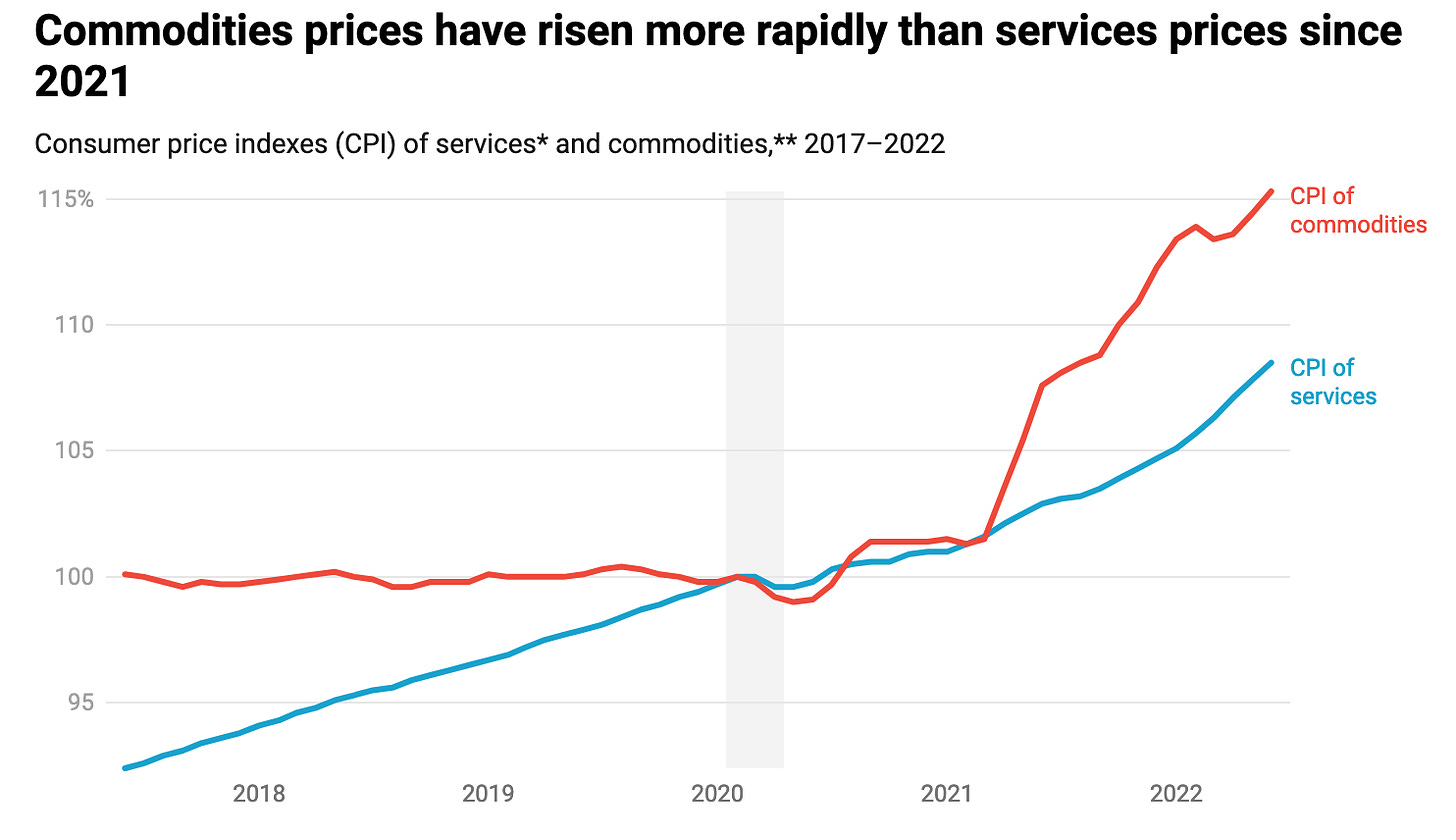

The Center for American Progress has put together an in depth study of inflation’s causes and effects. I encourage you to check out the whole thing, which includes a few illuminating charts and graphs like this one, which directly correlates post-recession supply-chain shocks with spikes in inflation:

And this chart, which shows that physical commodity prices have risen much higher than services, indicating that the supply chain does play a significant role in price increases:

CAP’s list of policy prescriptions at the end of the paper is targeted to directly address the physical causes of inflation—that is, the problem of moving goods from one place to another and hiring people to facilitate the creation and sale of those goods. They recommend incentivizing the adoption of Covid boosters, encouraging more immigration to fill out the workforce, providing paid family leave and childcare to get people back to work, and the other anti-monopoly and pro-green-energy policy prescriptions we’ve already discussed above.

For working Americans, the fight has just begun

We talk a lot in this newsletter about the “red-hot labor market” and the fact that workers have more power than at any other time in recent memory. It’s true, and it didn’t happen in a vacuum—the Economic Policy Institute listed all the Biden Administration’s pro-worker policies in one mammoth article.

But the fact is that workers had very few wins over the past forty years, leaving a lot of ground to make up. Dan Crawford at the Hub Project notes that it’s a big deal that the Biden Administration carved out a last-minute tentative agreement in the railroad workers’ labor dispute last week, but that dispute never would have happened had corporations not been allowed to rake in enormous profits while hacking away at worker rights for the last few decades. I recommend reading The New York Times’ deep dive into how the railroad industry “thrilled Wall Street” while repeatedly failing its workers—and customers.

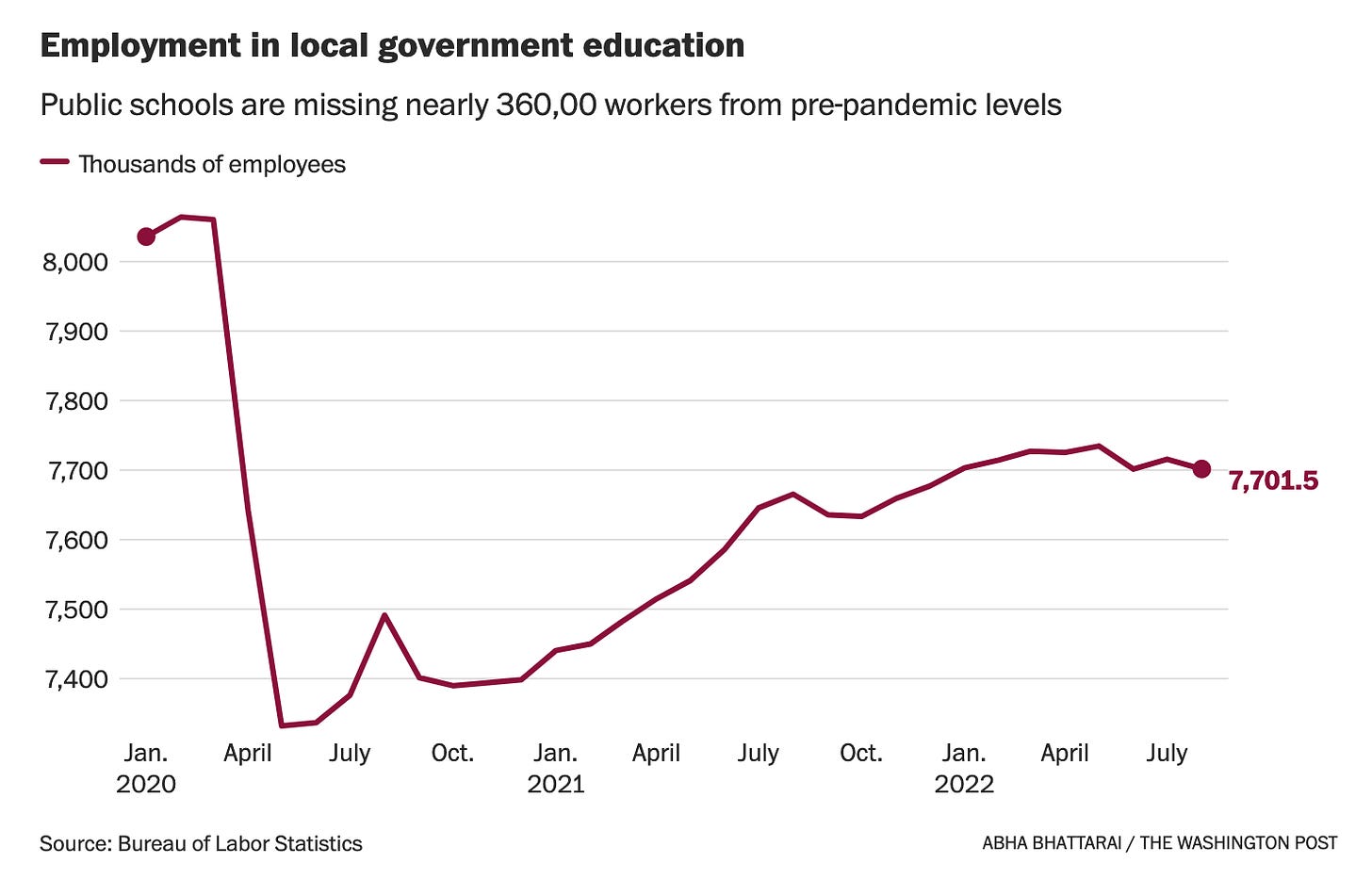

It’s not just railroads. Abha Bhattarai at the The Washington Post provides some excellent context to how workers in the education and healthcare industries have been nickel-and-dimed for generations, resulting in the worker shortages and strikes we’ve seen over the past few months. This isn’t about a single missed raise or a pandemic safety dispute: These workers are boiling over from decades of anger. Many of them have been shortchanged and understaffed for as long as they’ve been in their respective industries, and they’re not going to take it anymore.

For industries like nursing and public education, the losses during the pandemic were simply the metaphorical straw that broke the camel’s back, and no workers are stepping up to fill the gaps because the jobs pay too little and ask too much.

The good news is that we’re seeing progress around the nation. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom could lead the way on protecting work visas for some 300,000 foreign contract workers in the state, ensuring that California employers can find workers—if they’re willing to pay enough, of course.

And the Washington Center for Equitable Growth has some good advice for local leaders who still have unspent American Rescue Plan funds: They could support and enlarge their workforce by investing those funds into child care.

According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, the fiscal recovery funds can be used for child care support in a few different ways: ensuring “premium pay” for child care staff—up to an additional $13 per hour—similar to policies implemented in Kansas, Washington, DC, Utah, and elsewhere; providing loans or grants to repair child care facilities or help providers reopen or start a new facility; establishing technical assistance or programmatic support for smaller, home-based providers that need access to the subsidy system, expanding the supply and quality of care in the process; and offering expanded child care options for parents looking for work.

There are plenty of other policies federal and local leaders could adopt, and we’ll continue to highlight the best of them in the weeks to come. But the point is that just because worker gains over the last few months have been impressive and should be celebrated, we can’t forget that we have a lot of work to do. We’re not just making up the losses of the pandemic—we’re trying to make up the losses workers accrued over the entirety of the near half-century Trickle-Down Era. There’s a long way to go yet.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Join us at 10:30 am PT tomorrow for Civic Action Live, when we’ll discuss the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates to combat inflation, what our leaders should be doing to actually combat inflation, and why American workers are fighting to make up 40 years of losses.

On the Pitchfork Economics podcast, Goldy talks with Brookings economist Katie Bach about her stunning new report that analyzes the impact of long covid on the American labor market. Bach estimates that nearly 2 million workers have left the workforce due to symptoms of long Covid, and their lost wages and productivity have sapped the economy of billions of dollars.

Closing Thoughts

A Pitch reader named Kyle alerted me to Matt Breunig’s analysis of the poverty numbers that we shared in last week’s issue. The analysis takes issue with a report claiming that child poverty saw record drops in 2017 and 2018, and proposes that the huge decline actually resulted from a change in Census data categorization. These kinds of mistakes happen, and it’s important to correct the record when they do.

But even with that blip in the data, we know that we did actually see a record drop in child poverty in the 1990s when the earned-income tax credit was expanded, and then another one last year when the Child Tax Credit was sent to every American family. We know that anti-poverty programs prevented a spike in poverty in every single state in the union during the pandemic.

And thanks to new analysis of Census data, we know exactly what works in the fight against poverty: programs that get more money into people’s pockets. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities found that 2021’s dip in child poverty is the largest dating back to LBJ’s War on Poverty in 1967. CBPP found that “In the absence of the [Child Tax Credit] expansion, child poverty would have fallen to 8.1 percent, rather than 5.2 percent, and some 2.1 million more children would have lived in families with incomes below the poverty line.”

Health coverage, too, improved in 2021 thanks to programs expanding access to health care during the pandemic. “The uninsured rate fell to 8.3 percent, down from 8.6 percent in 2020 and 8.5 percent in 2018, prior to the pandemic,” CBPP notes. “For Black people, the decline in the uninsured rate was particularly steep, falling from 10.4 percent in 2020 to a record low of 9 percent in 2021.”

These findings are significant because they end a debate about government assistance that raged through much of the Reagan and Clinton administrations. Trickle-downers argued that the best way to fight poverty was only through targeted, technocratic, and means-tested assistance. Now, with all this new data from the pandemic, we see that it’s broad, cash-based assistance that truly makes a difference.

At this point, if you’re arguing against programs like the Child Tax Credit, it’s clear that you’re not interested in a debate about the effectiveness of policy outcomes—you just don’t want to improve outcomes for the lowest-earning Americans and their children.

But the fight against poverty matters for everyone in America. As Noah Smith recently noted on Substack, the problem at the root of American inequality is the fact that we have some incredibly rich people in this country, and also some incredibly poor people. If we can bring up the floor and increase participation in the economy, that spending will improve outcomes for everyone. Prosperity grows when everyone prospers, and now we know exactly how to do that. This is a cause for celebration.

Be kind. Be brave. Get vaccinated—and don’t forget your booster.

Zach