Friends,

For the Los Angeles Times, columnist Michael Hiltzik wrote about California’s $20 minimum wage for fast food workers, which went into effect in April of this year.

“For months before the wage increase, conservative pundits and economists filled the airwaves and newspaper columns with predictions that it would produce an employment bloodbath at fast-food restaurants,” Hiltzik writes.

Though corporate interests promised that the increased wage would kill jobs, “Two new analyses of the actual wage and price impacts of the $20-per-hour minimum have appeared this month,” Hiltzik says. “They employ slightly different statistics, but their conclusions are the same: There have been no job losses in fast food resulting from the increase. By some measures, employment has increased.”

The first report that Hiltzik writes about is the remarkable UC Berkeley study that I’ve written about here in The Pitch. That study, he explains, “found no measurable job losses, significant wage gains (as one might expect from raising the minimum wage to $20 from an average of less than $17), and modest price increases at the cash register averaging about 3.7% — far lower than the fast-food franchise lobby claimed were necessary” and totaling about 15 cents added to the cost of a $4 cheeseburger.

The second report “comes from a joint project of the Harvard Kennedy School and UC San Francisco. Not only did that survey find no job losses, but it also debunked claims or conjectures from minimum-wage critics that the increase would show up as reductions in hours or fringe benefits.”

Hiltzik quotes the authors of the study, who say that in response to the increased wage, “employers could have looked to cut costs by reducing fringe benefits such as health or dental insurance, paid sick time, or retirement benefits. We find no evidence of reductions.”

“The minimum wage issue occupies a peculiar place in economic analysis,” Hiltzik writes. “Many economists and commentators judge it by intuition — if you raise the price of something, such as the price of fast-food labor, conventional economics say you’ll get less of it. Hence, higher minimum wage, fewer jobs.”

“But it’s also among the most heavily studied of all economic phenomena, with the overwhelming majority of studies finding little or no employment effect from a higher minimum,” he concludes.

In the ten years since the Fight for $15 began, we’ve seen wages increase around the country, with none of the trickle-down threats of job losses or business closures actually materializing. The intuition of those experts who believed that every minimum-wage increase initiated a complicated series of negative effects has been completely disproven.

In my home of Seattle, one of the earliest battlefronts in the Fight for $15, the minimum wage next year will rise above $20 for the first time. Because Seattle’s $15 minimum wage phase-in included a 10-year slower rate increase for smaller businesses to see the benefits of increased consumer demand, this will also be Seattle’s first year with no subminimum wage for tipped employees at smaller businesses.

Civic Ventures fellow Paul Constant wrote about Seattle’s big minimum-wage milestone for the Urbanist.

Next year, thanks to cost-of-living adjustments written into the law to help working families deal with rising prices, Seattle’s new minimum wage of $20.76, or approximately $43,000 per year for a full time worker, will finally apply to all workers equally. That minimum wage, the long-awaited result of the Fight for $15, will be among the strongest in the nation.

Seattle’s promise to raise the wage has worked exactly as intended. Recently, anti-poverty organization Oxfam America issued a report finding that Washington State is the fifth best state in the nation for workers. Oxfam measured every state across three metrics, “wages, worker protections, and rights to organize,” and found that Washington state’s strong minimum wage helped our state stand out. So did the fact that Washington voters eliminated the subminimum wage for tipped workers in 1988, and voted twice more to maintain a high minimum wage for all workers. It’s no coincidence that Washington also consistently places among CNBC’s ranking of the top ten states for businesses. After all, when more workers have money to spend in their local communities, everyone prospers.

But when it comes to investing in workers, Paul writes, raising the minimum wage isn’t the endgame. In Seattle, as in most of the country, workers are facing dramatic spikes in housing costs, and child care costs are prohibitively high. Our leaders need to invest deeply in the people whose work makes the economy run, so that the economy can grow for everyone, Paul says, making communities “more affordable and livable for the vast majority of families and making the economy work for everyone — not just a wealthy few at the top.”

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Charts of the Week: Household Balance Sheets

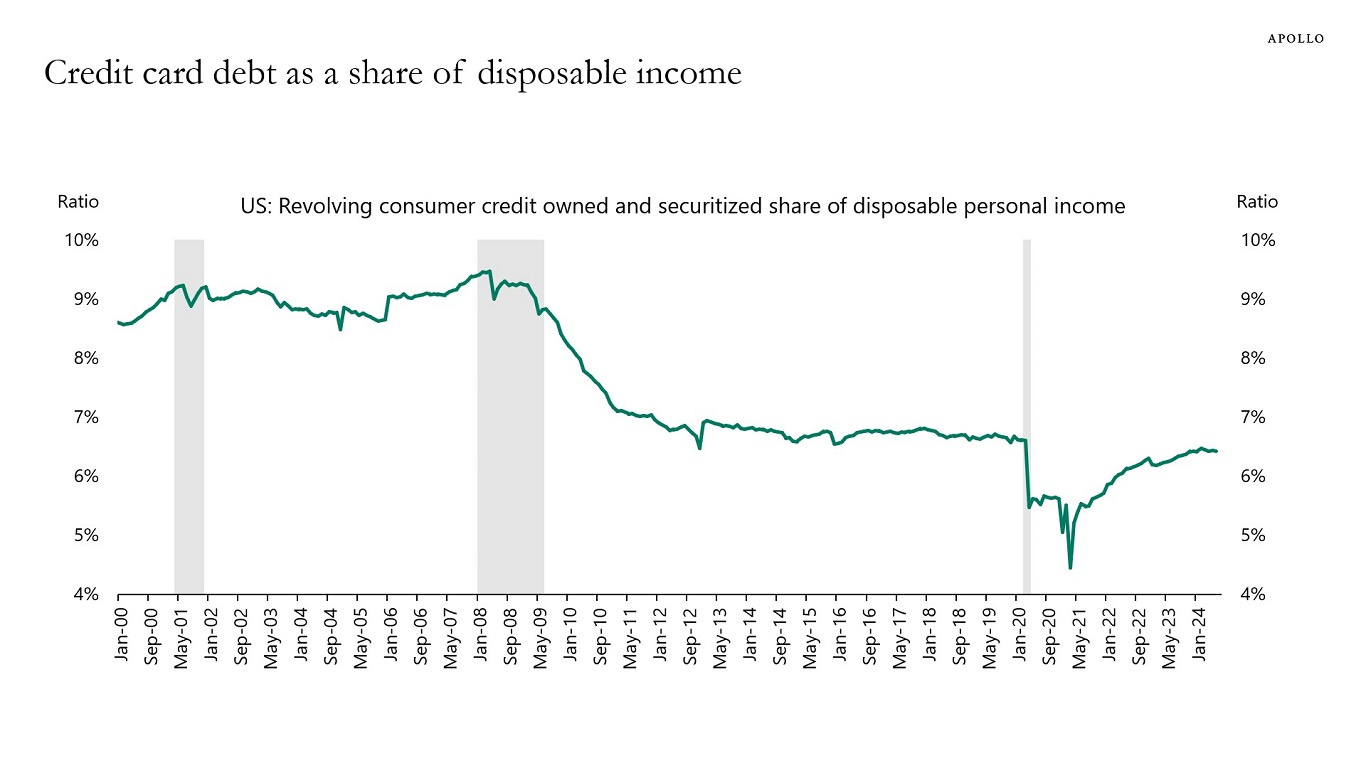

Torsten Sløk, the Chief Economist at Apollo Academy, the educational arm of investment platform Apollo, notes that ”the debt-to-income ratio looks much better for US households compared with other countries, including Canada and Australia.”

“At the same time, credit card debt for US households is at very low levels and declining,”Sløk adds. You can see in the chart below that debt dropped off at the beginning of the pandemic and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

This is great news, though we have to apply the usual caveats that charts like these tend to mask inequality—lower-income households often carry more credit card debt than upper-middle-class households, for instance, and white households are wealthier and less likely to carry debt than Black or Hispanic households. It would be a mistake to assume that all households are doing well, and we should shape our policy to invest in those households on the lower end of the scale so that everyone can do better.

But taken in the aggregate, Sløk notes, “US household balance sheets are in excellent shape. Combined with strong job growth, solid wage growth, rising asset prices, and the Fed cutting rates, there is no recession on the horizon.”

JP Morgan agrees with Sløk’s assessment, inspiring this remarkable Wall Street Journal headline:

This is not a “mission accomplished” moment. There’s lots of work to do, as I noted above. But it is important to note, after two solid years of corporations, neoliberal economists like Larry Summers, and big financial institutions threatening that a recession is around the corner, that those fears completely failed to materialize.

Petitions to Form Unions Doubled Under Biden

“There has been a doubling of petitions by workers to have union representation during President Joe Biden’s administration,” writes the Associated Press’s Josh Boak. “There were 3,286 petitions filed with the government in fiscal 2024, up from 1,638 in 2021. This marks the first increase in unionization petitions during a presidential term since Gerald Ford’s administration, which ended 48 years ago.”

It’s not a coincidence that union petitions diminished by roughly half during the four decades of trickle-down economic ascendancy. Countless laws were passed at the federal and state levels during that time to strip unions of their power and deregulate big employers. But all it took was one president with a middle-out economic platform to reignite the old enthusiasm for unions.

And the Biden Administration isn’t done yet: For the New York Times, Danielle Kaye reports that the National Labor Relations Board is arguing that even though Amazon delivery drivers are technically “employed by third-party logistics companies,” Amazon is legally considered to be “ a joint employer of drivers,” and so should be held responsible for alleged anti-union actions.

Kaye explains, “if the cases against Amazon prevail, they could eventually prompt a restructuring of the company’s last-mile delivery system and open the door to a wave of union organizing, labor experts said.”

Really, this push to unionize workplaces comes down to one of the most basic rules of politics: Nothing wins people over like winning. The Biden Administration has gone to bat for working Americans at every opportunity, and unions have won big as a result of that. Now workers are taking notice, and demanding their cut of the action.

Last Friday, Boeing announced that it would lay off 17,000 workers. Plenty of news organizations have laid the blame for these layoffs at the feet of unionized Boeing workers who have been striking for better wages and promises to play a major role in the manufacturing of Boeing’s future models. That’s simply not true.

If the media wanted to find a scapegoat for the layoffs, they would be wise to investigate the decades of trickle-down leadership that has consistently undercut well-trained workers and a culture of safety in exchange for runaway profit margins and nearly $60 billion in stock buybacks that handed away profits to shareholders with no strings attached. The costs of a six-week strike pale in comparison to those tens of billions of dollars that could have been invested back into the company in the form of higher wages, R&D, and quality assurance protocols.

Hurricanes Reveal Inequality in Our Economic Systems

“You might think that the insurance industry is going to suffer massive losses in the aftermath of Hurricanes Helene and Milton,” Robert Kuttner writes at the American Prospect. “Think again. Even as climate change has increased the ferocity of storms, the insurance industry has stayed well ahead of the game, not by working with consumers or with government to promote loss prevention and mitigation, but by hollowing out coverage.”

Insurers are swapping out coverage plans without homeowners’ knowledge, canceling plans, and pushing back against claims in an effort to prolong the process and outlast homeowners who cannot afford to wait. I encourage you to read the whole piece, which details all the ways that insurers are taking advantage of homeowners in high-hurricane-risk areas.

“According to Douglas Heller, the insurance director of the Consumer Federation of America, stories of the insurance industry incurring large losses because of hurricanes, floods, or wildfires are highly misleading,” Kuttner writes. They’ve rigged the game in their own favor so that insurers always win and homeowners always lose.

Here’s one eye-opening fact that explains this state of affairs: “In general, there is no federal regulation of insurance. That is precluded by the McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945, which bars most federal insurance regulation and leaves it to the states,” Kuttner writes. “The act was sponsored by two conservative Republicans to overrule a Supreme Court decision which held that the federal government under the Commerce Clause of the Constitution could regulate insurers, including subjecting them to the antitrust laws.”

Most of the time, breaking up insurance regulators into 50 different states works out in favor of the insurance companies. It’s easier for lobbyists to steamroll over politicians in state legislatures where there’s much less press attention. The whole point of a federal government is that it gives our leaders leverage in terms of power, financial strength, and attention against these wealthy corporations on behalf of American citizens. Things aren’t going to drastically change until our leaders undo this 80-year-old rule that has allowed insurers to run wild.

Hurricanes Helene and Milton have also revealed a tremendous inequality in our housing system. The New York Times notes that the back-to-back hurricanes “have exposed the risks climate change poses to the 16 million Americans who live in mobile or manufactured homes. Built in factories and lighter than conventional houses, manufactured homes are transported to a property and secured to the ground,” the Times explains.

Families that live in mobile homes are three times more likely to be impoverished than other Americans, and they’re also more likely to live in areas that are prone to disasters like flooding and hurricanes. Older mobile homes are particularly vulnerable to these disasters, and while modern mobile homes are subject to stronger safety regulations, there are fewer regulations that ensure the homes are properly installed, so they can be washed away by torrential rains, windstorms, and floods. At the same time, the wealthy people that build mobile homes—including Warren Buffet, who owns the biggest manufacturer of mobile homes in the country—are raking in billions of dollars in profit every year

And federal investments in disaster prevention tend to favor more expensive homes. “FEMA spends billions of dollars each year to protect communities against disasters like flooding by investing in bigger berms and storm pumps while elevating structures and other types of public infrastructure. But mobile home parks seldom benefit from that spending,” the Times notes. This is economic inequality at its purest level—a tiered housing system that ignores those at the bottom while favoring wealthier people in homes that are more likely to survive the intensity of the storms in the first place.

What the Fed Gets Wrong About the Economy

For the Wall Street Journal, James Mackintosh writes about the Federal Reserve’s “data dependency” problem. It’s an interesting piece that’s well worth your time.

“The Fed says it sets policy based on incoming data, especially on inflation and jobs. And those data have been both unreliable and far more volatile than usual, confusing investors into a series of rapid reversals,” Mackintosh begins. “The data point first to economic weakness and then, sometimes after revisions, strength.”

For instance, the Fed last month cut interest rates by half a percentage point in a response to flagging labor market numbers, hoping to juice the economy by making money cheaper to borrow. But Mackintosh notes that since that interest-rate cut, “economic data have come in much stronger than expected. The economy also appears strong. The weak jobs figures that spooked the Fed into a double cut of half a percentage point last month reversed in this month’s report, which was the third-strongest of the year. Live estimates of economic growth by the New York and Atlanta Feds are both above 3% for the third quarter, up from 2% in late August.”

So now we have the economic punditry class wondering if the economy is doing too well, and whether the Fed will respond by leaving interest rates flat for the next few months. It’s a ridiculous situation, and Mackintosh blames data dependency for causing it.

“Data dependency at the Fed has exacerbated what psychologists call recency bias in the market, with shifts in a couple of months of jobs or inflation data showing up in major moves,” he writes. In the end, “navigating a soft landing using the rearview mirror isn’t an option when it takes half a year or more for rate changes to have an effect on jobs and inflation,” Mackintosh concludes. “It is time for the Fed to kill its data dependency, and try to get investors to think about the longer run.”

This is an interesting theory, but I’d argue the problem isn’t an obsession with prioritizing recent data over long-term trends. Instead, the Fed’s understanding of economic growth is completely backwards. The Fed still treats the wealthiest Americans and most powerful corporations as the source of economic growth. Those interest-rate increases and decreases are intended to discourage and encourage CEOs and other captains of industry from investing in the economy.

This is a trickle-down perspective on the economy that is completely wrong. That’s why you had trickle-downers like Larry Summers cheering the Fed on to wipe out ten million jobs in order to get inflation in line—they believed that the wealthy people at the top of the economy had to slow the economy down in order to bring spending down. Those CEOs and corporate board members would have weathered the resulting economic downturn just fine—in fact, rich people get even richer after recessions—while millions of Americans would have dropped out of the eocnomy, creating a negative feedback loop for working families.

Thankfully, that’s not what actually happened. In fact, working Americans are the real job creators, and their spending is what kept the economy going long enough for the global price increases caused by pandemic-era shutdowns to abate. Their spending created jobs and tightened up the labor market, which helped American families survive the rampant price increases caused by corporate greedflation, when CEOs responded to the inflation spikes by raising prices simply because they could.

So what we have is economic leadership that is obsessed with the corner office when, in fact, it should be obsessed with growing the paychecks of American workers. Last month’s strong jobs report isn’t a warning sign for the Federal Reserve and a call to stop lowering interest rates—it’s a clear sign that the Fed is finally on the right track again.

This Week in Middle-Out

The New York Times looks at the very different child tax credit proposals from Vice President Kamala Harris and Donald Trump. Trump’s policy “denies the full benefit to the poorest quarter of children because their parents earn too little and owe no income tax,” while Harris’s plan would include those families on the lower end of the income scale, which we know from the pandemic-era CTC results in a rapid decrease in child poverty numbers.

Americans in 24 states will be able to directly file their taxes with the IRS for free next year, reports Axios. The limited trial run of the free filing program last year saw more than three million Americans file directly with the IRS, saving them more than $5 million in filing fees at firms like Intuit and H&R Block..

The New York Times looks at the Biden Administration’s investments in tribal nations, which “included $32 billion in short- and longer-term assistance for tribes and reservations: aid for households and tribal government coffers, community development grants, health services and infrastructure; as well as access to the $10 billion State Small Business Credit Initiative program, which previously excluded tribal nations.” That investment has reversed trends of poverty among Native Americans and spurred economic growth in tribal communities.

A new law in Maine helps mobile home owners buy the land that their homes sit on. It has already created “the largest resident-owned community in Maine,” after 300 mobile-home owners bought out their community’s landlord.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

This week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics is a reissue of a conversation Nick and Goldy had with Brendan Ballou, who serves as Special Counsel for Private Equity in the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, about why private equity is out of control. The last few years have seen more and more businesses under the sway of private equity, with workers laid off and value extracted from businesses ranging from Toys R Us to hospitals and veterinary clinics. This is a substantive conversation that digs into how we can unspool the damage caused by private equity.

Closing Thoughts

On Monday, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to three economists, Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson.

“They received the prize for their research into how institutions shape which countries become wealthy and prosperous — and how those structures came to exist in the first place,” writes Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times.

“The laureates delved into the world’s colonial past to trace how gaps emerged between nations, arguing that countries that started out with more inclusive institutions during the colonial period tended to become more prosperous,” Smialek explains.“ Their pioneering use of theory and data has helped to better explain the reasons for persistent inequality between nations, according to the Nobel committee.”

First, as a point of pride, I’d like to mention that we at Civic Ventures are very familiar with Acemoglu’s work in particular. Just last year, he appeared on an episode of our Pitchfork Economics podcast to discuss his latest book, laying out how wealthy people have traditionally profited from progress and technology, and explaining how economics can shift that paradigm so that technological progress works for everyone. And in 2019, he also appeared on a Pitchfork Economics episode about automation and work.

The work of this particular group of Nobel winners has been on our radar for a very long time. In fact, Acemoglu and Robinson’s book Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty was a foundational work of middle-out economics that helped Nick Hanauer and our team at Civic Ventures understand the scale and history of global wealth inequality.

The Prize committee honoring Johnson, Robinson, and Acemoglu with a Nobel is yet another sign of a dramatic shift in the economics profession. Their work is devoted to understanding the massive systemic and historic powers that shape a nation’s economic fortunes. They have measured the huge impact of what is essentially the international version of generational wealth, proving that not every nation begins with the same opportunities that others enjoy.

This might seem obvious to you or I, but it is a significant departure from classical economics. The Econ 101 understanding is that the free market is the perfect arbiter of winners and losers every time. If you are the best computer programmer in your labor market, Econ 101 assumes, you will rise to the top, and your pay will reflect your superior talent. By extension, if your nation sits on a unique store of mineral wealth, or if your soil and climate are better suited to growing certain fruits and vegetables, then your nation will prosper on the global stage.

So much of modern economics is devoted to proving that this old Econ 101 understanding of the world is, at best, a gross oversimplification and more likely a complete misunderstanding of how the world really works. The market is just one economic signal in a world full of them. Factors like where we were born, what family we were born into, and what kind of wealth we have access to are all significant determinants of how we’re likely to end up in life.

And these three economists just won the Nobel for proving that, by extension, no nation is destined to be impoverished—any number of factors, including its particular history of colonization, the power of neighboring nations, and its kind of governance, all play a role in determining whether a nation prospers or not. Their research indicates that a free and fair democracy is a powerful signal of a nation’s strong wealth—but that democracy alone “is not a panacea.”

“Representative government can be hard to introduce and volatile, for one thing,” Smialek explains in the Times. “And there are pathways to growth for countries that are not democracies, [Acemoglu] said, including rapidly tapping a nation’s resources to ramp up economic progress.”

Their research does conclusively show that authoritarianism does not cultivate a nation’s economic growth. When fewer people participate in their government, the economy suffers. But that doesn’t just mean democratic nations can rest on their laurels, either—they should consistently work to include more people in their democracies and their economies.

“Democracy needs to work harder, too,” Acemoglu explained in a press conference. “Many people are discontent, and many people feel like they don’t have a voice — and that’s not what democracy promises.”

These three Nobel Laureates are doing important work that pulls a number of complicated data streams together in order to create a more nuanced portrait of who gets what and why. Their work has helped to overturn decades of bad and lazy economic thought. But their findings are actually very straightforward: Life is better for everyone when more people have a better life. When we all participate in government and in economic growth, we all do better.

Onward and upward,

Zach