Friends,

This week, 47,000 International Longshoremen’s Association workers went on strike for the first time since 1977 at docks across the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico. Workers are demanding higher pay after years of inflation effectively shrunk worker paychecks.

President Biden, the Washington Post reports, is firmly on the side of workers. To the media, Biden “highlighted record profits” at the companies which employ the workers, “along with high executive pay and payouts to shareholders, as well as the shipping and port companies’ multinational ownership.”

Biden explained, “It’s only fair that workers, who put themselves at risk during the pandemic to keep ports open, see a meaningful increase in their wages as well.”

This is important because Biden has the legal power through the Taft-Hartley Act to order the workers back to work and order the union and their employers into an 80-day “cooling-off” session. But Biden has firmly closed the door on that option, telling reporters that he doesn’t “believe in Taft-Hartley.” Vice President Harris, too, has issued a strong statement of support for the striking workers.

Since it began less than five weeks before Election Day, this strike will serve as a political litmus test. Unlike, say, the United Auto Workers strike of earlier this year, American families are likely to feel some impact of this strike almost immediately. These ports combined handle more than half of the goods that enter the United States, so supply chain disruptions are sure to follow.

“The effects of the strike were immediately apparent Tuesday, with 38 container ships waiting at anchorages offshore, compared with just three Sunday, according to data firm Everstream Analytics,” the Washington Post notes. “Together they are carrying the equivalent of almost 270,000 twenty-foot long containers.”

Coverage of this strike will serve as an opportunity to observe the priorities of your preferred news organizations in action. When you read your favorite newspaper or website’s coverage of the strike, take note of where the paper explains the worker demands, and where and how it explains the impacts of the strike on consumers. Count how many CEOs and corporate spokespeople the reporters talk to, how many economists and what perspectives those economists are arguing for, and how many workers and union representatives they quote.

Peter S. Goodman’s table-setting piece published by the New York Times before the strike provides a fairly even-handed overview of the stakes that workers face. Goodman explains that dockworkers perform hard, dangerous work, and he asks the central question about automation that workers face in this strike: Who controls, and benefits from, technological advances? After all, if you replace all workers with robots, who’s going to be able to afford your goods? That’s a question that has gone unexamined for most of the trickle-down era, as big corporations shipped jobs and facilities overseas, but the dawning middle-out era has brought it back to the fore.

The port strike is unlikely to be the only labor movement in the headlines this fall. Stellantis workers will vote on a potential strike soon after their employer went back on promises made during the larger United Auto Workers strike earlier this year, including “promises to revive operations at a shuttered factory in Belvidere, Ill., and of planning to move production of the Dodge Durango, a large sport utility vehicle, from Detroit to Canada.”

Even the arts sector is getting into the act. National Symphony Orchestra performers went on strike against the Kennedy Center late last month. Their strike lasted less than a day before management put forth a tentative 18-month plan that workers agreed to.

“The new contract, according to the Kennedy Center, is valued at $1.8 million in new costs, and will increase wages by 4 percent in the first year and 4 percent in the second year, with negotiations to commence in early 2026,” the Washington Post reports. “The package also includes expanded health-care options, paid parental leave, updates to audition and tenure processes, and funding of a third full-time librarian position requested by the musicians. The new contract will bring the base salary for musicians to $165,268 in year one and $171,879 in year two.”

I have yet to see any reporters pick up on the “Crisp Labor Autumn” messaging I suggested a few weeks ago in The Pitch, but it seems clear that even though the labor market isn’t as hot as it was two years ago, workers are still emboldened to step up and demand higher wages, more benefits, and better working conditions. It’s a clear sign that after 40 years of wage cuts, merciless corporate profiteering from extractive globalization, and neoliberal anti-union cheerleading from politicians on both sides of the aisle, workers have gotten the middle-out memo and are ready to fight for what they’re worth.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Where Is the Economy Right Now?

In last Friday’s inflation report, we learned that August’s inflation rate came in at 2.2%, down from July’s 2.5% and very close to the 2% target that government agencies consider to be a healthy inflation rate. (I’m duty-bound to point out here that there is no real academic research behind the 2% ideal—it’s just the number that international agencies have settled on.)

“Altogether, the report offers further proof that price increases are swiftly fading,” reports Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell then announced that we could expect the Fed to lower interest rates twice more this year, though he seemed to suggest that we should expect quarter-point drops, rather than another big half-point cut in interest rates like the Fed delivered last month.

But the economy is still behaving in strange ways that confound economic experts. We’ve observed throughout the past few years that even as prices rose, consumer spending also stayed high, for instance.

And now, Axios’s Neal Irwin and Courtenay Brown report, there’s another case of mixed signals: “A common rule of thumb is that rising unemployment should coincide with a slowdown in economic growth,” they write. “That relationship looks broken. GDP in the second quarter was up 3% from a year earlier — a span in which the unemployment rate rose by half a percentage point.”

If I had to hazard a guess, I’d wager that GDP is strong because American paychecks are still growing faster than inflation, and that consumer spending has kept the economy strong. It also seems that the job market has slightly slowed recently because of the Fed’s efforts to keep interest rates high.

Another theory is that the job market is contracting because immigration to the United States has slowed down this year. “An influx of migrants in 2022 and 2023 enlarged the supply of workers and enabled rapid job growth despite an already tight labor market,” Irwin and Brown write. “A border clampdown this year may have reversed the trend, which would make a slowdown in job growth in the last few months less an alarming sign about the economy and more a mechanical effect of fewer new migrants entering the workforce.”

The Economy Is Strong, but Housing Affordability Is the Weak Link

Despite those mixed signals around prices and jobs, the economy seems to be in solid shape. Moody’s Analytics economist Mark Zaidi tweeted about this on Sunday. “I’ve hesitated to say this at the risk of sounding hyperbolic, but with last week’s big GDP revisions, there is no denying it: This is among the best performing economies in my 35+ years as an economist,” Zandi wrote.

“Economic growth is rip-roaring, with real GDP up 3% over the past year. Unemployment is low at near 4%, consistent with full employment. Inflation is fast closing in on Fed’s 2% target - grocery prices, rents and gas prices are flat to down over the past more than a year,” he continues. “Households’ financial obligations are light, and set to get lighter with the Fed cutting rates.”

Zandi acknowledges the real problems facing American workers: “lower-income households are struggling financially, there is a severe shortage of affordable homes, and the government is running large budget deficits. And things could change quickly. There are plenty of threats,” he writes. “But in my time as an economist, the economy has rarely looked better.”

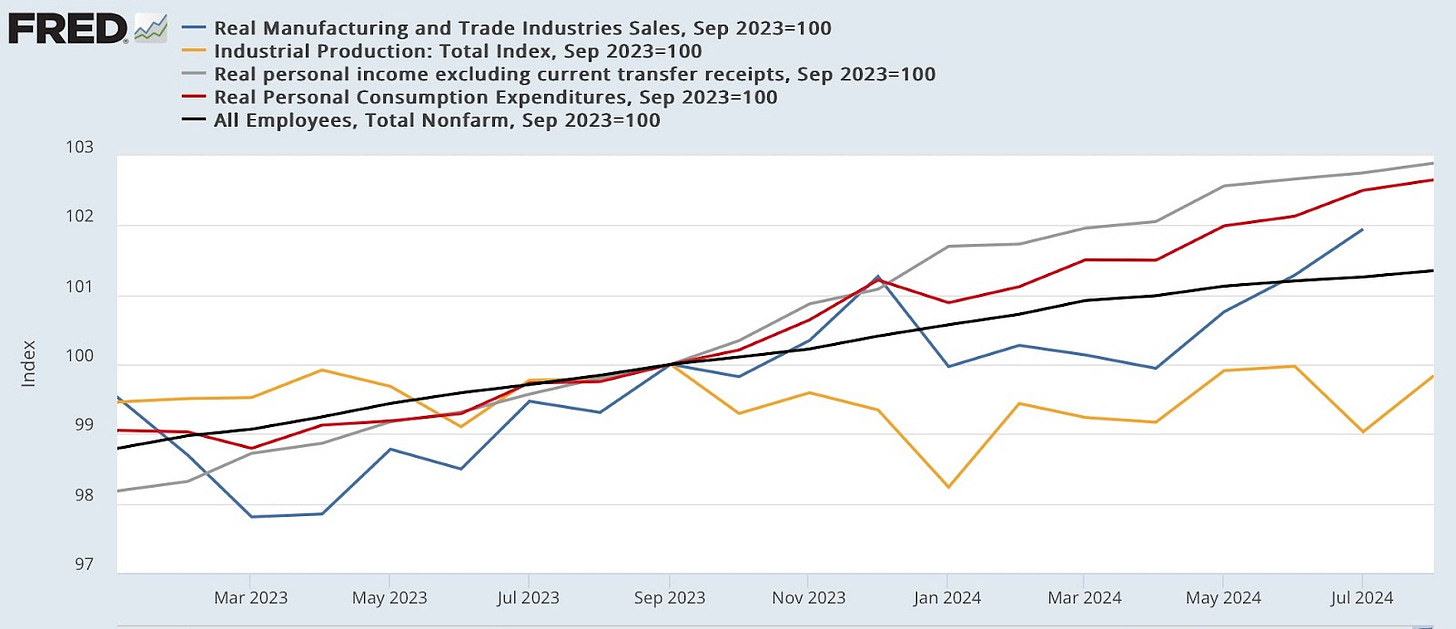

Angry Bear Blog agrees with Zandi, noting that since just before the pandemic “real disposable income is up 10.6%,” and the economic “nowcast,” which measures “real income (less government transfers), real sales, real spending, industrial production, and jobs,” is up by every metric except for industrial production, which has been down for the entire 21st century as China began to dominate the global industrial space.

But our strong economy is not evenly distributed. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the biggest economic issue of the year is the skyrocketing price of housing. Far and away, rising housing costs are causing the most misery for working Americans, and leaders must work to find solutions to this problem as soon as possible. I wrote at length about housing last week, so I’ll direct you there for more information. But I did want to highlight two graphics that were circulating around social media on Tuesday night after the VP debate, which included a lengthy segment on housing. The first is a graphic that compares the Republican and Democratic housing plans…

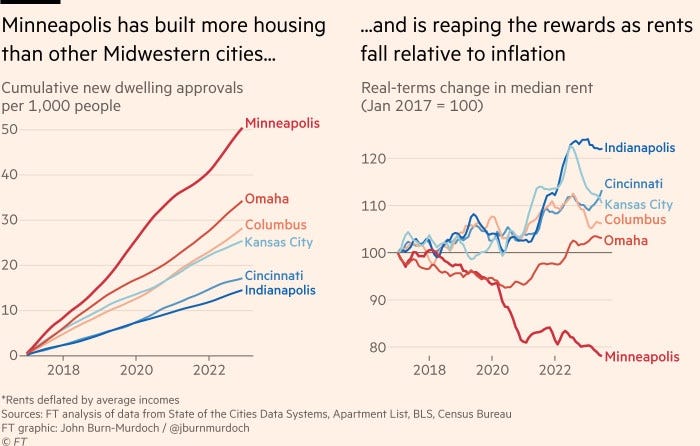

…and the second is a graphic showing the direct correlation between housing construction and housing prices:

If your housing plan calls for the construction of housing on federally owned land, which is often far away from populated areas, and for the forced deportation of millions of people who don’t own homes in order to somehow make housing more affordable, you don’t have a serious housing plan.

Examining California’s $20 Fast-Food Worker Minimum Wage

You may recall that the state of California recently established a first-in-the-nation sectoral wage policy, in which a Fast Food Council made up of workers and business owners would establish working conditions, training standards, and a minimum wage for fast food restaurants in the state. That council established a fast food minimum wage of $20 per hour, and a new study from UC Berkeley examined the effects of that minimum wage on workers and customers.

First, and most importantly, the researchers discovered that raising the minimum wage “increased average hourly pay by a remarkable 18 percent, and yet it did not reduce employment.”

For customers, the researchers found that the increased minimum wage “increased prices about 3.7 percent, or about 15 cents on a $4 hamburger (on a one-time basis), contrary to industry claims of larger increases.”

They continue:

About 62 percent of the increased costs were passed on to consumers in higher prices, suggesting that restaurant profit margins, which were above competitive levels before the policy, absorbed a substantial share of the cost increase. Since demand for fast food is highly price-inelastic, the price increases likely raised restaurant revenue.

I don’t know about you, but I’m happy to pay 15 cents more for a hamburger if it means that workers are paid a wage that means they can afford to eat in restaurants, too. This study is yet another data point in a vast and growing body of evidence that shows raising the minimum wage doesn’t kill jobs and close businesses—in fact, it grows the economy for everyone.

This Week in Middle-Out

Michigan lawmakers are considering two bills that could make their state a leader in the care economy. According to Ethan Bakuli at Capital & Main. “one bill would formalize standards for [home care workers]. The other enables workers in Michigan’s Home Help Program to collectively bargain for wages, benefits and training statewide.” These bills would cover some 35,000 home care workers in the state of Michigan.

MSNBC reporter Ali Velshi’s conversation with Biden Administration Trade Representative Ambassador Katherine Tai is a peek into what it means to have a middle-out trade policy. “Trickle-down just doesn’t work,” Tai said, adding that “Tariffs and trade can and – in our view – must be used as part of a strategy for growing the middle class and empowering the working class.”

“Latino entrepreneur growth rates over the past decade have risen 10 times more than non-Latino business rates,” writes Beto Yarce, the Pacific Northwest administrator of the US Small Business Association, for the Spokane Journal of Business. That’s a significant share of the more than 19 million small businesses that have been created since President Biden took office.

Congressional Democrats wrote letters to nearly three dozen companies that have paid their CEOs more than they’ve paid in taxes since the Trump tax plan was signed into law in 2017. According to the letter, those “35 companies raked in $277 billion in domestic profits and paid their executives $9.5 billion—more than they paid in federal income taxes." The Democrats were spurred to action by a recent report which found that CEO pay “has soared 1,085% since 1978 compared with a 24% rise in typical workers’ pay.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Sociologist Nikhil Goyal joins Nick and Goldy on the podcast this week to talk about his new book, Live to See the Day: Coming of Age in American Poverty. By focusing on the lives of three young people living in Kensington, Philadelphia, Goyal illustrates the effects of intergenerational poverty on a micro scale. While most episodes of Pitchfork Economics are focused on larger policy issues and heady conversations about economic theory, this one gets into exactly what effects those economic policies have on individuals. And it just so happens that Goldy was born in Kensington, so he offers an even more personal perspective on the experiences detailed in Goyal’s book.

Closing Thoughts

It seems that you can’t visit a news site anymore without bumping into a story about private equity behaving badly. The varied ways that private equity squeezes profits out of the misery of the American people are so inventive and elaborate that some of them sound like the master plot of a James Bond villain.

At the Guardian, Damian Gayle writes, “Private equity firms are using US public sector workers’ retirement savings to fund fossil fuel projects pumping more than a billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere every year.” Gayle explains that private equity organizations “have plowed more than $1 trillion into the energy sector since 2010.”

Those workers—and in some cases even the pension managers—might not know that their retirement investments are funding pollution that exacerbates climate change. Gayle explains that private equity scoops up dangerous and unclean assets which even the banks that fund Big Oil consider to be “risky investments. Thanks to limited disclosure rules, regulatory loopholes and complex corporate structures, some of the dirtiest assets have come to be owned by relatively obscure investment outfits,” and they’re funded by the retirement accounts of average American workers.

The American Prospect reports that another private equity firm leeched some $850 million from BioLab, the company behind the toxic east Atlanta chemical fire that forced 90,000 Georgians to shelter in their homes over the weekend. BioLab’s safety record seems to be getting worse and worse—another chemical fire in Louisiana this summer was at a BioLab facility, for instance—and it’s not too hard to draw a line between the company’s cavalier handling of toxic chemicals and the nearly billion dollars that have been airlifted away from the company to line the pockets of their PE overlords.

Also at the Prospect, Luke Goldstein writes that private equity firms have bought up Video Relay Services, which he explains is “a niche area of telecommunications connecting deaf people to sign language interpreters at call centers around the country, so that they can communicate with family and friends, conduct work, or even call in medical emergencies.“

These services are funded by the federal government, but they’re managed by, you guessed it, two private equity firms. Those firms love Video Relay Services “because they can fleece a taxpayer slush fund with few repercussions for degrading product quality for deaf people and squeezing workers. Despite receiving an increase in government subsidies last year, those funds haven’t trickled down to workers in wages and benefits.” Goldstein reports on a culture of union busting and unfair labor practices at relay services.

And we can’t forget that private equity has its claws deep into the American medical system. The CEO of Dallas-based Steward Health Care abruptly resigned after he failed to appear before a Senate panel investigating how Steward imploded. The company, which is owned by a private equity firm, quickly offloaded nine Massachusetts hospitals after running out of money. The company’s hospitals have also racked up long lists of patient safety issues including preventable deaths.

In all of these cases, no one person is to blame. There’s not a single CEO who can be thrown in prison and publicly disgraced to put an end to this behavior. In fact, these outcomes are the logical end result of private equity. Let me put it another way: These chemical fires, patient deaths, and climate catastrophes are what happens when private equity behaves exactly as expected. When you deregulate financial markets, you get complicated firms that buy up troubled and niche assets, pump them full of debt, slash wages and lay off workers, and then suck out all the profits.

The European Union and the United States are looking more closely at applying a regulatory structure to private equity. Senator Elizabeth Warren has sponsored a bill called the Stop Wall Street Looting Act that would prevent some of the worst of these behaviors. Without regulatory structures in place, the extraction, devaluation, and collapse of targeted companies is the whole point of private equity. Stopping that kind of behavior, and instead diverting the financial sector’s energies toward serving the public good, is the whole point of regulation.

Onward and upward,

Zach