Our Housing Price Crisis Is a Trickle-Down Problem

The Pitch: Economic Update for September 26th, 2024

Friends,

After years of watching housing prices soar, we’re finally starting to see real policy solutions that could address the scope of America’s housing crisis.

First, one of Vice President Harris’s first announced policies as a presidential candidate was a bold commitment to building three million units of housing in her potential first term, with a focus on starter homes and a $25,000 incentive for first-time homebuyers.

But other substantial housing policies have been announced in the days since. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Tina Smith co-authored an op-ed for the New York Times laying out a broad plan to build more affordable housing in America.

Their plan would “establish a new, federally backed development authority to finance and build homes in big cities and small towns across America.” The authority would ensure that homes are “built to last by union workers and then turned over to entities that agree to manage them for permanent affordability,” including “public and tribal housing authorities, cooperatives, tenant unions, community land trusts, nonprofits and local governments.”

“To fund social housing construction,” Smith and Ocasio-Cortez explain, “our development authority would rely on a combination of congressional spending and Treasury-backed loans, making financing resilient to the volatility of our housing market and the political winds of the annual appropriations process.”

They also explain that it’s important to “repeal the Faircloth Amendment, which prevents the construction of new public housing,” explaining that the 1998 law, which was passed “with the support of both parties,” has “helped entrench a cycle of stigmatization and disinvestment.”

I want to stay on that point for a moment: The Faircloth Amendment was a trickle-down deregulation bill that basically capped the number of public housing units that could be built with federal funds at 1999 levels. This means that federal leaders haven’t been able to respond to millennials, an even larger generation than the postwar Baby Boomers, flooding into the housing market. In other words, the federal government has been handcuffed by trickle-down regulations as housing prices have soared and hundreds of thousands of Americans have become unhoused.

Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer addressed that last point in a piece for the Nation back in February of 2020. He argued that the growing number of unhoused Americans is, at root, an economic problem. “Despite all the fearful rhetoric about addiction, mental illness, and crime, our homelessness crisis is largely driven by a shortage of affordable housing—and affordability is simply the quotient of income divided by cost,” Nick wrote. “The math is simple: Across America, housing costs have been rising faster than incomes for decades, with every $100 increase in median rent entailing a 15 percent increase in homelessness. And trickle-down economics is largely to blame.”

And trickle-down has made housing affordability such an all-encompassing issue that even the federal government alone can’t solve it. We need local and state lawmakers to take action that is specifically tailored to regional housing needs.

A few weeks ago, I mentioned in The Pitch that in King County, which encompasses my home of Seattle, a County Councilmember named Girmay Zahilay proposed a Regional Workforce Housing Initiative,” which aims to direct “at least $1 billion in excess debt capacity to build and maintain rent-restricted housing units, with rents set to reflect the true cost of development and operation.” And next year, Seattle voters will have their say on an initiative that would fund the city’s newly formed social housing developer program.

The surge in housing prices is making America unaffordable for far too many people. It’s punishing the middle class and forcing a whole swath of the poorest Americans onto the streets. It’s preventing too many American families from generating wealth and finding a path to economic stability. All of which is to say that this is not a problem that can be solved with one simple fix. It requires a “yes, and” mindset—we need bold leaders at all levels of government to reject the trickle-down housing model and instead come up with solutions that rebuild housing in America with a middle-out mindset.

Those who understand the scope of our housing crisis understand that the localities that don’t address the problem by adding huge amounts of housing will likely find themselves left behind in the years to come. On housing, there are really only two paths forward: A middle-out approach that invests in working families and directs the public and private sector toward outcomes that work for everyone, and a trickle-down approach that treats housing as another way to hoard wealth in the hands of a few, at the expense of everyone else.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Where the 2024 Presidential Candidates Stand on Economic Policy

Yesterday, Vice President Kamala Harris delivered a speech at the Economic Club of Pittsburgh that outlined her economic plans in greater detail. Harris made the case for empowering the American middle class by both cutting costs and also improving opportunities for them to grow their wages. Doing so, she argued, would establish “strong shared economic growth” for everyone in the economy, not just the wealthy few at the top. For instance, she made the call to encourage affordable child and senior care because “when that happens, our economy as a whole grows stronger,” as the Americans who previously had to stay home to take care of the most vulnerable members of their families are allowed to rejoin the workforce.

Harris also outlined plans to encourage growth in American industries that would make us more resilient and less reliant on other nations. For the Washington Post, Jeff Stein explained that Harris laid out “a policy push she hadn’t previously backed: Government industrial policy to promote specific economic sectors. She in particular referenced, among other industries, Artificial Intelligence, quantum computing, clean energy manufacturing and aerospace.” Just as the Biden Administration encouraged the manufacturing of semiconductors here on American soil, a potential Harris administration would work with private businesses to invest in growing technologies with an American workforce.

During the speech, Harris’s aides handed out an 84-page policy book (PDF) outlining the specifics of those policy plans. There’s simply too much policy to include everything here, but it fleshes out Harris’s previously stated plan to lower grocery costs and housing costs for Americans. In addition to a first-ever national ban on price-gouging, Harris seeks to promote small businesses and competition in both the food production and grocery retail business, for example, and on the housing side she seeks to create tax incentives in order to direct the private construction and real estate industries to fill the huge demand gap among lower-income Americans who need housing.

With its call to invest in American workers while also incentivizing private businesses to prepare for the future, Harris’s plan follows the tenets of middle-out economics. She understands that the economy grows from the middle out, not the top down—and she also understands that the resulting economic growth is good for everyone in the economy.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump’s economic plans are getting more scrutiny as the election approaches. Alan Rappeport at the New York Times outlines points made by Trump in an economic-focused speech he delivered on Tuesday: “The former president proposed creating ‘special’ economic zones on federal land, areas that he said would enjoy low taxes and relaxed regulations,” Rappeport explains.

Trump also “called for companies that produce their products in the United States — regardless of where their headquarters are — to pay a corporate tax rate of 15 percent, down from the current rate of 21 percent. Businesses that try to route cars and other products into the United States from countries like Mexico would face tariffs as high as 200 percent.”

As their economic plans become clearer, it’s more and more obvious that these two candidates are at opposite ends of the spectrum: While Harris understands that economic growth comes from working-class Americans, Trump seems to keep trying to find more and more elaborate ways to get more and more money into the hands of the wealthiest people and corporations, with the promise that that increased wealth will trickle down eventually.

While the difference between the two candidates has probably been clear to readers of The Pitch for a while now, the fact is that a growing number of Americans are noticing the difference between the Harris and Trump economic plans. That’s at least part of the reason why a growing number of voters are positively rating Harris’s understanding of the economy when compared to Trump.

Which Grocery Monopoly Do You Live Under?

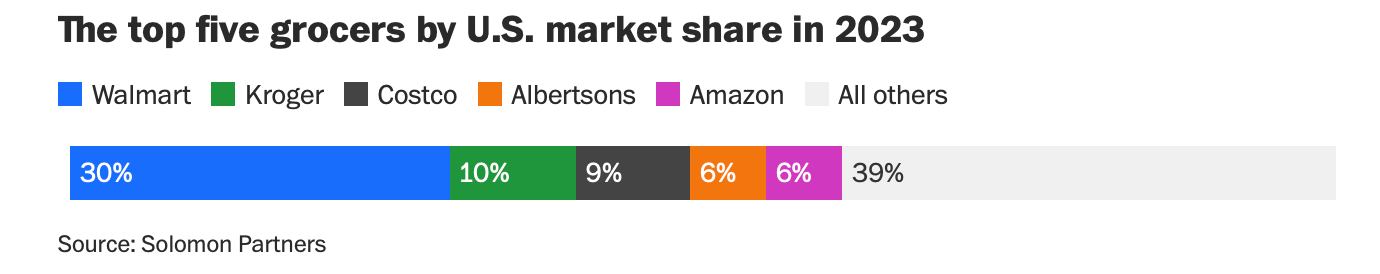

The Washington Post has put together a fascinating feature demonstrating the lack of competition nationwide in the grocery industry. “In 2023, just three corporations — Walmart, Kroger and Costco — generated about half of the $1 trillion in U.S. grocery sales,” the Post notes.

The popular perception of a monopoly is one corporation owning the vast majority of an industry, and so most mainstream Econ 101 professors would probably argue that the above graph doesn’t demonstrate monopoly control over the grocery industry. Even the biggest grocery chain, Walmart, doesn’t quite control a full third of the market. But the problem is the unfettered free market that economists have always held up as the most efficient way to solve problems isn’t actually available to Americans.

While the above graph makes it look like all Americans can choose from a broad wide range of grocery-store options, including five major players and a robust market of other options that makes up 40 percent of all grocery stores, the truth is that we are geographically bound to our local grocery store market. And most of us live in a place where one or two chains absolutely dominate the market.

Or, as a lawyer for the Federal Trade Commission recently argued in a court in Oregon, “If a shopper in Portland is faced with higher prices, they can’t practically go somewhere in Eugene” to buy their groceries.

For example, here’s the Washington Post’s breakdown of the grocery stores in King County, WA, where I live:

About 116 of the 330 grocery stores in King County are owned by either Albertsons or Kroger. And you also have to bear in mind that King County is immense—over 2000 square miles in total and encompassing more than 40 towns and cities with a total population of 2.2 million people, which means that many residents have a much smaller range of options within 30 minutes of their homes.

And all of the above is even worse when you remember that Albertsons is currently trying to merge with Kroger, which would put over a third of all grocery stores in King County under the control of one enormous grocery chain. That’s why the FTC is arguing to break up the merger before it happens, and states like Colorado and Washington are also combating the potential merger.

What the Post doesn’t do is connect the final set of dots: This march to consolidation helped to make the greedflation we saw at grocery stores over the last three years possible. If the market for grocery stores was truly competitive, stores would have pushed back on the exorbitantly higher prices that manufacturers were charging in order to jack up their profit margins. But, since most of the big five grocers dominate particular regions of the country, their customers had no choice but to pay. And then the grocers themselves got in on the act, hiking up prices even further.

In a Fiery Speech, Government Antitrust Crusader Calls Out Economic Academia

Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter, who heads the Antitrust Division of the Justice Department, recently delivered a speech that offered a scathing assessment of economics experts. Specifically, Kanter insinuated that the wealthiest people and corporations have bought access into, and sway over, many of the learning institutions that educate new economists and inform leaders who establish and defend the financial rule of law.

“All over the world, money earmarked specifically to discourage antitrust and competition law enforcement is finding its way into the expert community upon which we all depend,” Kanter said, adding that “conflicts of interest and capture have become so rampant and commonplace that it is increasingly rare to encounter a truly neutral academic expert.”

“If a paper was shadow-funded or influenced by corporate money, it can pass that influence and whatever flaws or biases it introduced into the papers that build on it,” Kanter argued, adding that “this insidious ripple effect is difficult — if not nearly impossible — to detect.”

What does this ripple effect look like? “Academic consultants can make as much as $1,000 an hour as experts for companies trying to merge; one University of Chicago professor named Dennis Carlton has earned over $100 million from work like this,” Robert Kuttner explains. “Corporate consulting is frequently not disclosed in academic or popular writing. Judges are taught through corporate-underwritten events, like one coming up next month at George Mason’s Law and Economics Center on blockchain and crypto, how to rule in cases involving corporate interests.”

Peter Coy talked to University of Miami law professor John Newman, who explained that “People who cloak themselves in the trappings of neutrality are taking advantage of the good will and reputation that professors at universities have built up over centuries without suffering the sacrifices that go with that.”

There are no binding rules that forbid this kind of coziness between big corporate interests and academics. But the end result of all this money flowing into the hands of the people who do the research that influences our laws is that the power dynamic between the haves and the have-nots continues to grow in favor of the super-rich—and those protections become enshrined in law.

In the last decade or so, that corruption has been an open secret, whispered about in private but never spoken aloud. Kanter finally called it out in public, and in so doing, he shined a spotlight on system-wide corruption. It will take years of hard work to untangle this network of conflicts of interest and academic payola, but thanks to Kanter, it can no longer be ignored.

This Week in Middle-Out

Striking Boeing workers in Washington state say they’re willing to hold out “as long as it takes” for the company to meet their demands of higher wages and a restored pension system.

Meanwhile dockworkers at ports on the East Coast and the Gulf Coast are preparing to go on strike on October 1st. These workers earn roughly a third less than their West Coast counterparts, and are demanding raises that bring them on par with their peers.

The National Labor Relations Board is trying to make Trader Joe’s recognize a union in one of its New York stores. Meanwhile, workers at a second Apple Store have ratified a union contract.

The Department of Justice has sued Visa for monopolizing debit card transactions, which the DoJ argues “affects the price of nearly everything.” Americans make about 100 billion debit card transactions nearly every day, and Visa has a hand in roughly 60% of them.

The Federal Trade Commission took action against the three biggest pharmacy benefit managers in the nation, accusing them of inflating insulin prices for working Americans. “The legal action targets CVS Health’s Caremark, Cigna’s Express Scripts and UnitedHealth’s Optum Rx,” reports the New York Times, and the three are accused of “inflating insulin prices and steering patients toward higher-cost insulin products to increase their profits.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

The podcast celebrates its milestone 300th episode with a look back at some of the very best answers to the questions that Nick and Goldy ask all their guests: Why do you do this work? Nick and Goldy reflect on the amazing assemblage of economic talent that has appeared on the podcast in the last 300 episodes, and they also, for the very first time, answer the question themselves.

Closing Thoughts

I wanted to call your attention to last Sunday’s 60 Minutes profile of FTC Chair Lina Khan. Reporter Lesley Stahl follows Khan, the youngest FTC Chair in history, on a series of listening tours around the United States. It’s an important profile of one of the most consequential members of the Biden Administration, and the whole video serves as a compelling introduction to middle-out economics.

From the very top of the video, when Khan explains the importance of competition in a capitalist market to ordinary citizens who have come out to hear her speak, you can tell she’s a talented economic communicator.

“Too often fewer and fewer companies are controlling more and more of the market. And what that means is companies can start ripping you off, hiking prices, stealing from you,” Khan said. She immediately turned that into an indictment of greedflation, in which big corporations jack up the costs on products in service of pumping up their profit margins.

And then there’s this exchange:

Lesley Stahl: What about the argument that when companies merge prices often come down, because of efficiencies, scale?

Lina Khan: But even if those efficiencies arise, if the company's not checked by competition it won't have an incentive to pass those benefits on to the consumer because those consumers may not have anywhere else to go.

In her short time as FTC head, Khan has collected a seemingly bottomless arsenal of examples of rampant corporate malfeasance. She shows Stahl a tiny piece of plastic attached to the cap of an asthma inhaler that a company used to extend the patent on that asthma inhaler. As a result, the inhaler is sold for $7 in France, where the patent extension wasn’t granted, and the exact same device sells for $500 in the United States.

“Khan's doggedness represents a shift in policy, a mandate to reverse decades of a hands-off strategy toward mergers and acquisitions,” Stahl reports. “It was introduced by Ronald Reagan and adopted by all presidents since, including Clinton and Obama, until President Biden put an end to it.”

Stahl doesn’t use so many words, but she’s describing the monopolistic worldview of trickle-down economics. And she correctly identifies President Biden, and Biden staffers like Kahn, as the first leaders to consistently do battle with trickle-down economics in more than 40 years.

Even in this hyper-siloed digital age, a 60 Minutes profile still carries a lot of weight in today’s media environment. And this profile of Khan comes at an interesting time. As Vice President Kamala Harris’s campaign began picking up steam this summer, reports started leaking that big Democratic donors—the billionaire class and CEOs—began pressuring Harris to fire Khan if she were to win the presidency this fall.

Khan should wear those donor complaints as a badge of honor: If some of the wealthiest people in the country want you fired because you’re blocking corporate mergers and fighting to keep prices down for ordinary workers, you must be doing something right.

Harris hasn’t spoken one way or the other about whether she would retain Khan in a potential Harris White House. But this 60 Minutes profile arrives at just the right time to accurately portray Khan as exactly the kind of middle-out champion the American people need in charge at the FTC. Hopefully Harris will take notice—because the American people sure have, and they approve of what Khan is doing.

Onward and upward,

Zach