Friends,

If you’re reading this email, you’re almost certainly interested in the developing progressive economic response to trickle-down economics. For over 40 years, leaders in both parties were captured by the lie that economic policies which benefited the wealthiest Americans and corporations would create economic prosperity for everyone else. You’re no doubt familiar with its tenets: tax cuts for the rich grow the economy, regulations harm the economy, and rising wages are bad for the economy. These lies are practically treated as gospel, repeated ad nauseum in halls of power, cable news and Twitter hot takes.

It’s not remarkable that the rich and powerful have figured out how to justify making them more rich and more powerful as an economic benefit for everyone else. It’s a trick as old as time. The remarkable thing is that there was no coherent economic response to these trickle-down lies from the progressive left.

For most of our lifetimes, the left has made moral arguments for policies benefiting the middle- and working-class, and remained completely silent on their broad economic benefits. By not explaining how the economy really works, they effectively abandoned the average person, giving them permission to accept the trickle-down frame that whatever is good for workers is bad for the economy.

Of course, it didn’t used to be this way. For most of the 20th century, American leaders on the left knew that ordinary Americans, not CEOs, were the real job creators—and the economy boomed as a result of it.

Things are now changing very quickly. The dominant trickle-down economic narrative is crumbling and giving way to a new understanding: the point of economic policy should be to help the American worker because this creates economic prosperity for everyone. Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer helped coin the phrase “middle-out economics” years ago, but President Biden has popularized the term throughout his presidential campaign and, especially, over the summer as he signed economic policies benefiting ordinary Americans into law.

This month, journalist Michael Tomasky published a new book digging into the history of this remarkable economic paradigm shift. It’s titled The Middle Out: The Rise of Progressive Economics and a Return to Shared Prosperity, and it serves as both an overview of the economic history of the current paradigm shift and a survey of the leaders in the up-and-coming field of middle-out economics. To my knowledge, this is the first book documenting this pivot in economic history, though it’s certain not to be the last.

Tomasky is plugged into the political zeitgeist, and this book reports on one of the most underrated stories of the moment. I encourage you to read The Middle Out and share it with your friends and family to get the message out about the importance of this moment—and what’s at stake in the coming midterm elections.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Inflation ticks up in a cloud of mixed economic signals

This week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that inflation ticked up 0.1% in July—a significant slowdown from the skyrocketing inflation we saw earlier this year, but a disappointing sign for economists who were hoping to see a drop after last month’s flat inflation report. Even with plummeting gas prices, it seems that housing and grocery prices rose high enough to push inflation slightly higher.

Robert Kuttner at The American Prospect argues that inflation is subsiding “based on a variety of indicators and the economy heading for the proverbial soft landing without a recession—if the Fed doesn’t screw things up with excessive interest rate hikes.” He cites two economists who argue that we’re a long way away from inflation becoming “embedded” in the economy, using several metrics to back up those arguments.

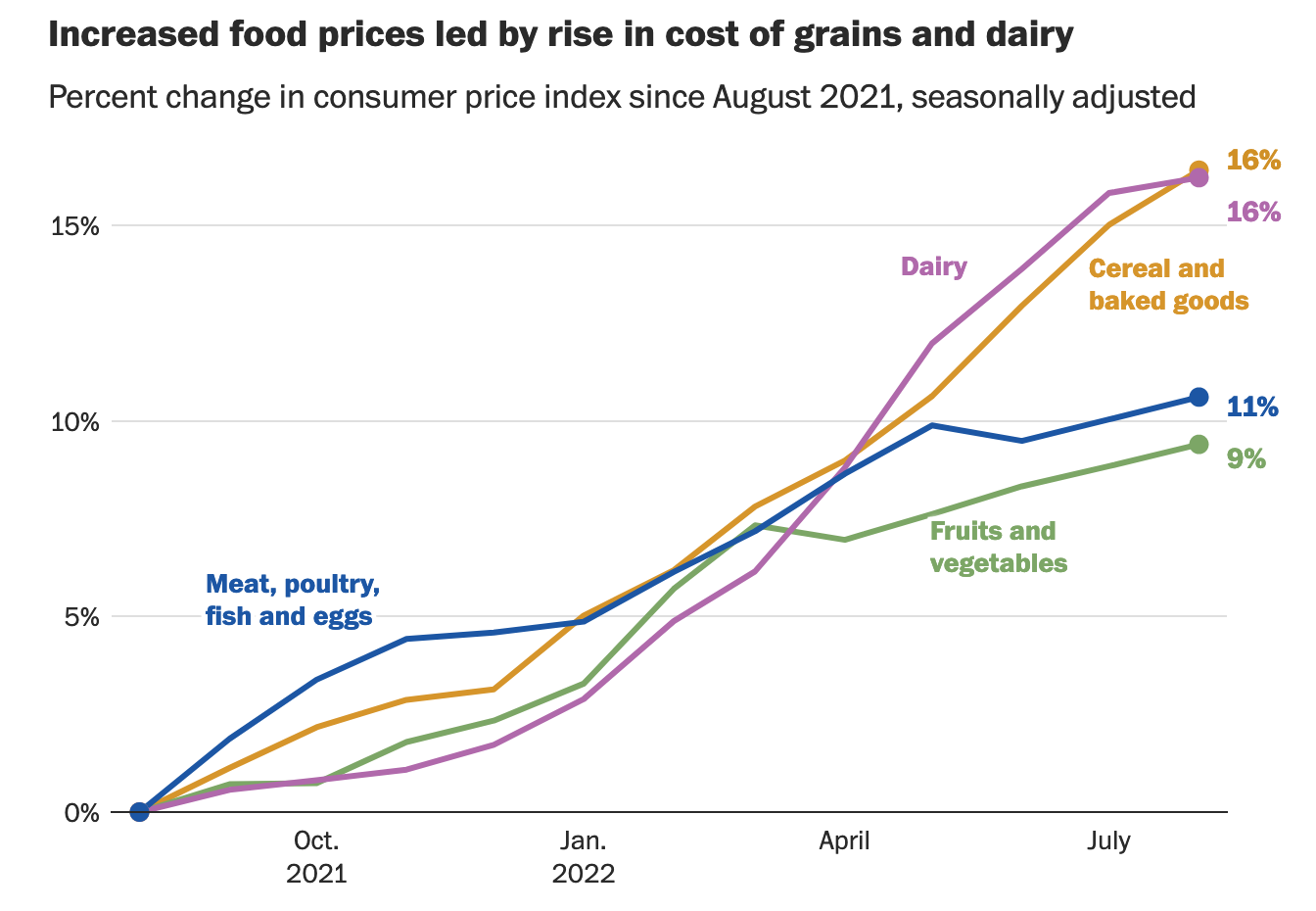

The Washington Post’s Alyssa Fowers and Rachel Siegal did a deep dive into which prices are rising, which are dropping, and how much they’ve increased over the past year. One of the biggest pressure on our wallets is food and grocery prices, and this chart demonstrates how dramatic those increases have been:

At Forbes, former Whole Foods VP Errol Schweizer looks at how the industries that are driving our inflationary price hikes—including transportation, retail, and food producers—are all reporting record profits while also raising prices sky-high. It’s a clear-eyed report from an expert in food and retail policy, and I especially found a lot to appreciate in his paragraph about solutions:

There are policy measures that may ease the pain. The Emergency Price Stabilization Act, introduced by Congressman Jamaal Bowman (D-N.Y.), would tackle supply side price hikes and recommend the use of price controls to limit price increases in key goods and services. Price controls during WW2 kept profits in check while strengthening consumer spending power. Windfall profit taxes and expanded unionization could redistribute the gains more equitably. The USDA has rolled out compelling programs to develop regionally distributed food supply chains. The FTC has stepped up antitrust scrutiny, alongside Congressional hearings investigating grocery consolidation. And worker representation on corporate boards could bring some balance to corporate governance above and beyond timid ESG measures.

Meanwhile, the housing market is cooling around the country, and mortgage rates just hit 6.3%—the highest they’ve been in over two decades, which will very likely slow home purchases even further. And the Federal Reserve’s insistence on going full-steam ahead on rate hikes means that those mortgage rates will almost certainly go even higher. It seems likely that housing prices will continue to drop, though energy costs are a big question mark as we head into cooler autumn months.

Ben Casselman and Lauren Leatherby at the New York Times do a good job of laying out the bizarre contours of our current economy. They explain that the job market is still incredibly strong, and that even though wages have declined when taking price increases into account, incomes are stronger than at comparable times during other economic downturns. This might explain why retail sales and consumer spending are also up compared to historically similar times. At the same time, manufacturing isn’t showing the same kind of slumps that we’ve seen in the past, and the housing market is definitely behaving as though we are living in recessionary times.

“A slowdown that stays confined to one or two sectors doesn’t constitute a recession, which by definition involves a sustained decline in activity across a broad swath of the economy,” the authors conclude. Whatever economic weirdness we’re experiencing right now doesn’t match the accepted definition of a recession—in fact, it defies labels.

Making great strides in the fight against poverty

Jason DeParle at the New York Times shares some unabashedly excellent economic news:

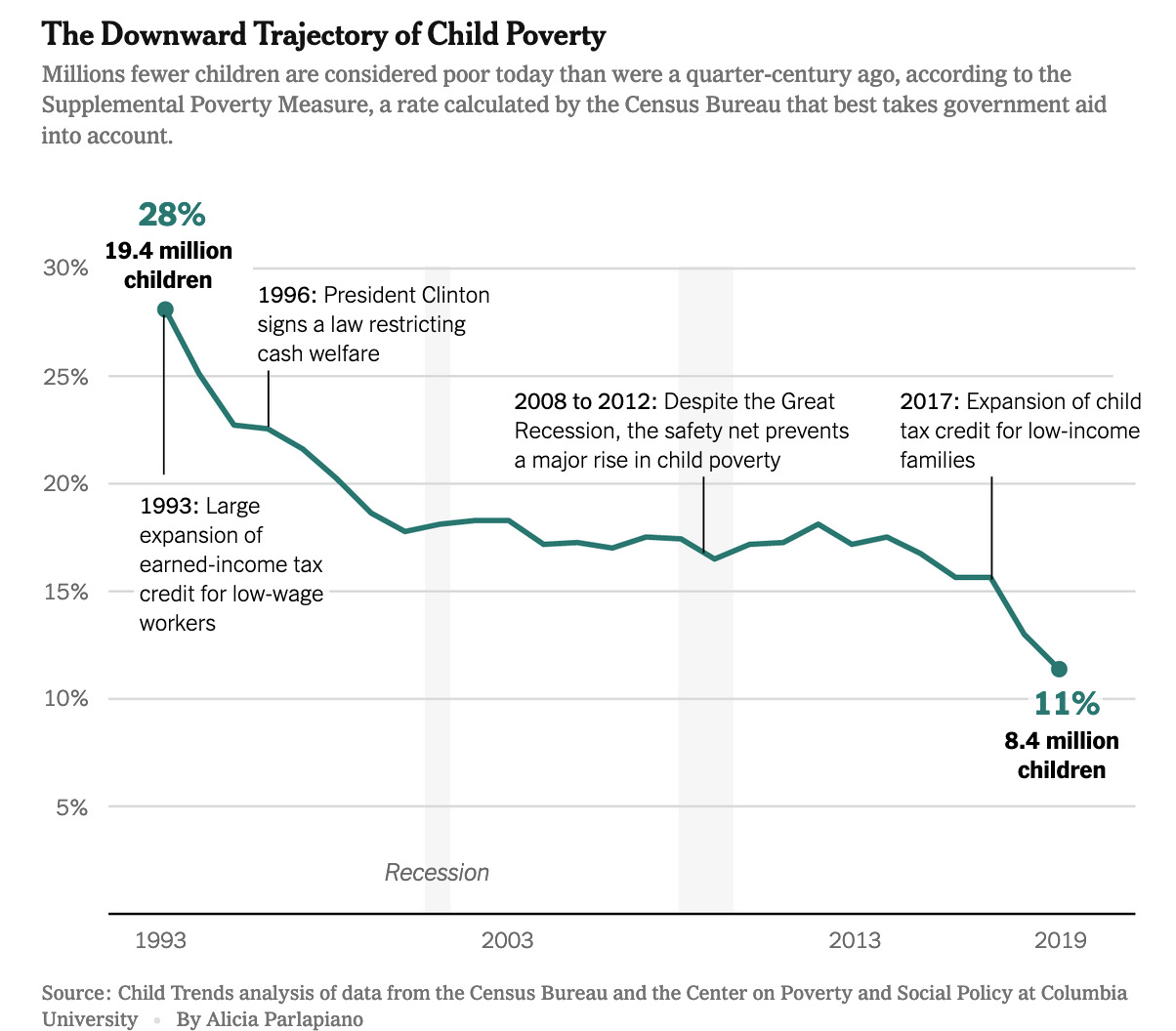

A comprehensive new analysis shows that child poverty has fallen 59 percent since 1993, with need receding on nearly every front. Child poverty has fallen in every state, and it has fallen by about the same degree among children who are white, Black, Hispanic and Asian, living with one parent or two, and in native or immigrant households.

This is not the result of any single policy, though “lower unemployment, increased labor force participation among single mothers and the growth of state-level minimum wages” all play a part, and “the expansion of government aid” deserves a majority of the credit.

Last year saw another huge decrease in the poverty rate, from 9.2 percent to 7.8 percent, with child poverty dropping to 5.2 percent in part thanks to the temporary Child Tax Credit, which Congress allowed to lapse at the end of the year. It’s likely that at this time next year we’ll see a rare uptick in poverty numbers because senators like Joe Manchin failed to make effective government investments in children permanent.

New research on two policies that could promote economic inclusion

Kurtis Lee reports on an important economic policy trend: Since the year 2020, roughly 50 American cities have launched some form of guaranteed basic income pilot program. These GBI programs send hundreds of Americans a few hundred dollars every month with no strings attached. As expected, research from these programs is starting to come in.

One study among recipients of GBI in Stockton, California “found that 28 percent of recipients had full-time employment when the program started in February 2019; a year later, the figure was 40 percent,” Lee writes. How could giving people money result in more employment? For one thing, being poor in America actually takes up a lot of time and energy—poor people have to jump through a series of hoops just to qualify for aid. Without all that unnecessary work, people finally have the time and energy to find a good job, not some exploitative position that treats them like a disposable cog until they burn out and quit.

Another policy that would help with the dissemination and management of GBI payments is public banking. The Roosevelt Institute issued a policy brief explaining how a publicly owned bank would increase savings, end exclusionary racist and sexist banking policies that prevent millions from managing their money in a responsible way, and end the exploitative system of fines and fees that banks use to penalize poor people using their services.

Where did the workforce go?

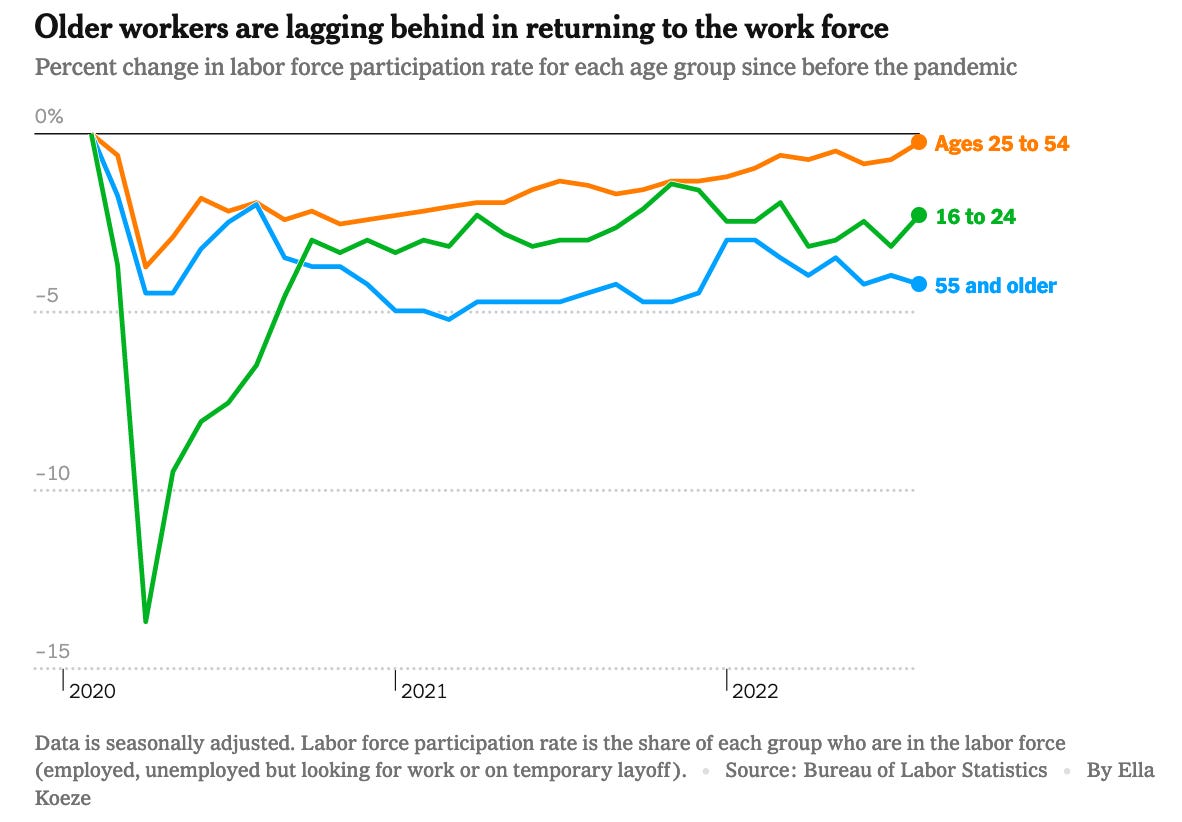

Lydia DePillis at the New York Times interviews some of the Americans who left the workforce at the beginning of the pandemic but have not yet gone back to work. Some of her findings are unsurprising—workers over 55 are more reluctant to rejoin the workforce–but a few of the findings are more unexpected, like the fact that men have been slower to rejoin the workforce than women.

Many of these workers are suffering from long Covid and other health problems. Others want more flexibility than a full-time job will provide them.

This kind of workforce disruption is to be expected after a global pandemic, of course, and we’re really talking about a tiny fraction of people—the vast majority of Americans are back at work. But this gap in labor participation will likely cause long-term ripple effects in the economy as people need financial support and employers compete to bring past employees back into the workforce.

Change is difficult

Greg Ip at the Wall Street Journal reports that the bipartisan CHIPS Act, which invests in American semiconductor manufacturing to prevent future supply chain difficulties, is less popular with Wall Street investors, who have been profiting from China’s low-wage manufacturing industries for decades. It’s another reminder that change—particularly change away from extractive-but-profitable practices—is difficult.

Ezra Klein, for instance, notes that President Biden’s legacy is hinging on the question of whether the physical achievements of his legislative accomplishments—electric car charging stations, manufacturing plants, clean energy infrastructure—can be built in a timely manner. “We haven’t built on this scale, in this country, in decades,” Klein writes, and because political winds in this country are fickle, time is of the essence.

At the same time, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is forcing European leaders to make big energy infrastructure investments of their own. This is a U-turn from the austerity budgets that European leaders embraced over the past decade, and this quote from economist Frank van Lerven should be familiar for any American feeling exasperated at the economic ruin inspired by trickle-down economics:

“For the last ten years and more, we’ve been told that workers and pensioners and the young all have to make sacrifices and we need to live within our means. We’ve seen degrading infrastructure, our health system deteriorated.”

“It was all for nought,” he concluded. “The dogma has been clearly exposed as a narrow political ideology, devoid of macroeconomic thinking, weaponized for narrow political ends.”

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Join us at 10:30 am PT tomorrow for Civic Action Live, when we’ll talk about the week’s biggest economics news, including what the latest inflation numbers mean, the latest developments in the railroad workers labor dispute, and why it’s a big deal that we’re winning the war on poverty.

On the Pitchfork Economics podcast, Nick and Goldy talk with journalist Marcus Baram about his incredible work exploring what the disintegration of overtime standards means for workers around the country. This episode really looks at overtime pay from every angle—from Nick’s realization as an employer that paying overtime has value to Marcus’s conversations with workers who don’t even know that their grandparents used to earn overtime for every hour worked over 40 per week—and it’s a great case for restoring overtime protections to the same levels as when the American middle class was at its strongest in the 1970s.

And Nick joined the Do One Better! podcast with Alberto Lidiji this week to discuss why philanthropy is great, but philanthropic giving alone will not end the scourge of massive income inequality. This is a fascinating conversation about creating change in the world.

Closing Thoughts

Over the past year, most of the conversations about labor unions have revolved around Starbucks employees, Amazon warehouses, and workers at stores like REI and Trader Joe’s. But Americans everywhere are using union power to demand higher pay and better working conditions. For instance, this week 15,000 Minnesota nurses went on strike in the largest public-sector strike of its kind in American history.

And until this morning, railroad workers were on track to launch a strike that potentially could have disrupted transportation and supply chains across the country. That all changed when the Biden Administration announced that they had come to a tentative agreement between the unions and railroad owners. The deal is still subject to ratification by worker vote, so there’s still a long way to the finish line. But it’s still a big accomplishment for a president who has repeatedly centered working Americans in his economic policies.

In the days leading up to today’s announcement, there was a lot of coverage of what a potential strike might mean for ordinary Americans, but much less coverage of what the workers actually wanted from their employers. The Washington Post deserves immense credit for talking directly to labor about their demands. For these workers, their most important demand is not about pay—it’s about time:

Conductors and engineers say that they can be on call for 14 consecutive days without a break and that they do not receive a single sick day, paid or unpaid.

“All we’re asking is folks to be able to go to routine doctor’s visits without pay, but they have refused to accept our proposals,” said Dennis Pierce, president of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen (BLET). “The average American would not know that we get fired for going to the doctor. This one thing has our members most enraged. We have guys who were punished for taking time off for a heart attack and covid. It’s inhumane.”

These workers are compensated well for their time, and they generally received a few weeks of vacation a year and a handful of personal days, but employers demanded them to request time off far in advance. Of course, most health concerns don’t bend to the demands of a schedule. Lauren Kaori Gurley and Jeff Stein report that this unrealistic expectation from railroad bosses was what pushed the White House to take a stand: “Biden had grown animated in recent days about the lack of scheduling flexibility for workers, expressing a mixture of confusion and anger that management was refusing to budge on that point.”

This is a growing front in the ongoing fight for worker power. Here in Seattle, Civic Ventures was part of a push for secure scheduling laws, which call for retail and restaurant employers to give employees two weeks’ advance notice of what their schedules will be. If they diverge from those pre-posted schedules, employers have to compensate their workers for their time. And of course we’re big supporters of restoring the overtime threshold so salaried employees are compensated for time that they put in above and beyond 40 hours a week.

The reason for this is simple: Time is money, and every worker’s time counts. Employers compensate workers for the labor they put in on the clock; they have no right to extend their influence into the hours when the worker is not on the clock. Technology has made it too easy for every worker to be continually available and perennially busy. And these always-on schedules also detract from local economies: What good is a $95,000 annual salary, as some of these railroad workers were earning, if they don’t have any time to spend that money in their community? What good is earning a living if you don’t have time to invest in hobbies, further education, career development, and quality time with friends and family?

Hopefully the White House’s involvement on the behalf of railroad workers will create a national conversation around this invisible cost of labor. The price of a potential strike may be incredibly high, but the cost that’s been extracted from their personal lives—and from our local economies—is too high to ignore any longer.

Be kind. Be brave. Get vaccinated—and don’t forget your booster.

Zach