Friends,

We’re still in the first hundred days of the second Trump administration, and the uncertainty surrounding Trump’s tariff program has thrown the entire economy into turmoil. Remember, the huge tariffs that caused chaos in global markets two weeks ago are theoretically only on a 90-day pause, and consumers are just starting to see the result of the near-universal 10% tariffs that Trump enacted—not to mention the 145% tariffs on Chinese products.

Economics is not a science, and nobody can accurately predict what’s going to happen in the next few weeks and months. That’s why consumer and business sentiment surveys, which we’ll explore later on in this issue, are so important right now—when nobody knows what’s going to happen, the uncertainty itself becomes a meaningful factor in how the economy behaves.

If you’re looking for some kind of insight into what might happen Barry Ritholz at the Big Picture blog has put together a post laying out three potential futures for the program of tariffs—a best-case scenario, a middle scenario, and a worst-case scenario. Ritholz is an astute economic observer, and the scenarios he lays out are clear-headed and easy to understand.

And if you’re still struggling to understand how high tariffs will impact nearly every item you encounter while shopping, you should read this thread by Derek Guy, who has risen to social-media fame as “the menswear guy.” Guy explains how tariffs impact a simple $100 pair of sneakers that you might buy at the local Foot Locker store, driving up prices every step of the way and putting retailers in peril.

But remember that when the tariffs are levied, they aren’t distributed evenly across the economy. David Dayen at The American Prospect got a hold of a letter that giant grocery retailer Albertsons sent to suppliers in the days before the Trump Administration levied huge tariffs across the board. That letter informed grocery suppliers that “with few exceptions, we are not accepting cost increases due to tariffs.”

“In other words,” Dayen explains, “regardless of higher supplier costs from components of their goods sourced from China or other countries, [suppliers] would have to absorb those increases if they want to sell to Albertsons.”

Tariffs will raise prices up and down the supply chain for groceries. We just mentioned above that retailers will pay more for their products and then pass the higher prices on to customers. How, then, can Albertsons simply refuse to pay those higher prices? The answer is clear: Monopoly power.

“Albertsons holds a significant market share in the grocery market, particularly in the western United States. Competitors like Walmart and Kroger are even bigger (Albertsons unsuccessfully tried to merge with Kroger last year),” Dayen explains. “Independent grocers, however, typically don’t have the same ability to dictate terms to suppliers, and therefore will have to take whatever they can get.”

Because they control access to millions of consumers, monopolies have the power to force their suppliers to swallow the higher costs, while smaller competitors do not. And given their behavior during the pandemic, when Kroger and Albertsons both raised prices higher than costs and pocketed the additional revenue as pure profits, it’s not too big of a leap to believe that even if Albertsons does avoid paying higher tariffs by squeezing their suppliers, they might still take advantage of a high-tariff environment by charging customers at their grocery stores more in order to boost their profits.

Some businesses, though, are being very transparent about their price increases. As Natasha Khan reports for the Wall Street Journal, “companies are starting to tack tariff surcharges onto invoices as a separate line item.”

Some of the line items, Khan reports, “are a $5 flat fee, while others represent as much as 40% of the subtotal. The tactic is a way to pass on at least some tariff costs to consumers—especially on Chinese-made goods, with levies totaling 145% since January—while passing the buck to President Trump.”

“I’m not sure the average person truly understands that this is going to cost them more money everywhere,” one executive of a showerhead company told Khan, mentioning that he is also encouraging other businesses to add tariff notifications to their invoices and bills.

Some business leaders—such as BigBadToyStore’s founder and president, Joel Boblit—are emailing detailed letters to their customers explaining how the tariffs will affect their supply chains. On Wednesday evening, after Trump paused most tariff increases but not for China, Boblit told customers that the Wisconsin company would apply a tariff-related fee to preordered items.

“I absolutely hate increasing prices to you, but the tariff situation is beyond our control,” he wrote, pledging to reduce or remove the charge if the tariffs declined.

He told customers they could cancel if they didn’t want to pay the additional fee. The charges would be 15% to 40% of the preorder price, he estimated.

Americans have been doing business under a cloud of uncertainty for two months now, and the tariff situation continues to be kicked down the road, rather than settled. As we’ll see in the next section of this newsletter, Americans have communicated in the clearest language possible that they’re concerned about these tariffs and are likely to hold back on purchases if they’re kept in place.

At this point, tariffs aren’t just a staring contest between the Trump Administration and other nations—it’s a staring contest between the Trump Administration and American workers. And since workers are the true job creators and the source of growth in the American economy, we’d better hope, for all our sakes, that Trump blinks first.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

American Manufacturers Expect the Economy to Go Downhill

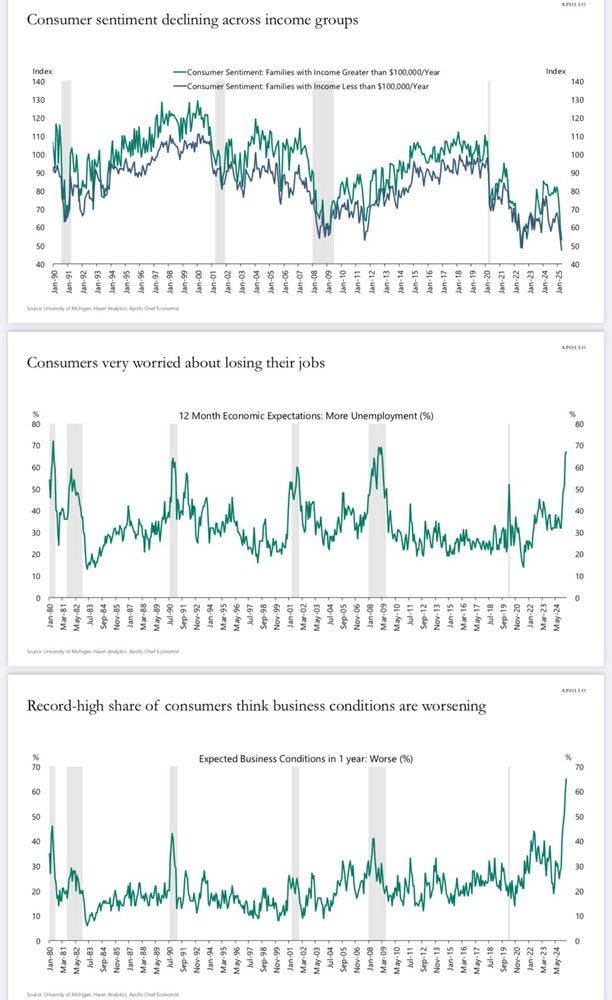

The changes happening across our federal government are happening very quickly, but our economic models are still functioning at their traditional cautious speed. Until we start to get concrete data showing how tariffs and the widespread cuts across the federal government have affected the economy, we have to continue to rely on sentiment reports, which show how people feel about these changes and how those changes will affect their daily lives. Torsten Sløk, the chief economist at Apollo Academy, has compiled a report that reflects how dire American sentiment about the economy has become in the past few weeks. The latest data shows that American consumer confidence is now weaker than it was during the 2008 economic crisis, and that “consumers’ worries about losing their jobs are at levels normally seen during recessions.”

At the same time, “Households’ income expectations are declining,” and “Inflation expectations are rising at an unprecedented speed.” Most remarkably, these feelings of economic insecurity are shared “both for households making more than $100,000 and less than $100,000.” It’s very rare to see that kind of shared sentiment all the way up and down the wage scale—another indicator that the current uncertainty is abnormal.

Meanwhile, the New York Federal Reserve’s monthly survey of manufacturers also shows dismal expectations for the next six months on every metric from new orders to hiring to “general business conditions,” which the Fed reports has fallen “to its second lowest reading in the more than twenty-year history of the survey.”

“Firms expect conditions to worsen in the months ahead, a level of pessimism that has only occurred a handful of times in the history of the survey,” the New York Fed concludes. And this survey seems to be backed up by real-world results: We’ve already seen several manufacturers lay off workers due to earlier tariffs established by the Administration.

“Late last month, in response to the metals tariffs, the steelmaker Cleveland-Cliffs laid off more than 1,200 workers across Michigan and Minnesota. In California, the window-maker Milgard Manufacturing is laying off nearly 400 workers and shuttering its Ventura County factory,” writes Nitish Pahwa for Slate. “Thousands more factory workers have recently been axed in industries ranging from tractors to food production, batteries and electronics, sports apparel, packaging, construction, and board games.”

The economy is very complex and prone to defying our expectations. It’s impossible to say whether any of these assumptions will prove to be correct. But when American manufacturers—the same group of people that the Trump Administration claims to want to help with this wave of tariffs—are nearing historic low levels of confidence, you have to wonder who is actually benefiting from these tariff policies. Senator Cory Booker, among others, has his suspicions.

Home Ownership Is Out of Reach for a Majority of Americans

“The average rate on the popular 30-year fixed mortgage surged 13 basis points Friday to 7.1%,” writes Diana Olick at CNBC. “That’s the highest rate since mid-February.” Emily Peck at Axios notes that those mortgage rates are spiking because the Trump Administration’s tariff shock “sparked a Treasury bond selloff,” which made the cost of borrowing skyrocket.

Peck also notes that tariffs are driving up construction costs: “60% of builders said their materials costs have gone up by an average of 6.3% this year, adding $10,900 per average single-family home.” The home construction industry is anticipating higher prices for imported lumber and other materials, which is slowing down construction rates.

“Forget about housing in this environment, with mortgage rates back up, consumers certainly concerned about the job market, housing will also be on the weak side,” Nancy Lazar, chief global economist at Piper Sandler, said on Friday.

These high mortgage rates, in conjunction with high housing prices, are putting home ownership out of reach for tens of millions of Americans. “The median price of a new single-family home in the U.S. is about $460,000, according to the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), a trade group for residential construction companies,” writes Tobias Burns at The Hill. “Based on mortgage rates at 6.5 percent and current underwriting standards from banks, that price is out of range for about three-quarters of all U.S. households, the NAHB found in March.” Of course, now mortgage rates are about a half a point higher than the rate the NAHB used to calculate those totals, which is probably pushing housing out of reach for more families.

And it doesn’t get much better if you’re bargain hunting for fixer-uppers in less desirable areas. “Even houses that cost $300,000, substantially less than the median sales price of $398,000 for existing homes in February, are too expensive for 57 percent of households,” Burns writes.

In January, Zillow projected that home prices would rise 2.9% in 2025. In February, Zillow lowered their projection to 1.1%, citing the economic uncertainty we were discussing earlier. Then, in March Zillow lowered its projection of home price increases again, this time to 0.8%. Higher mortgage rates could easily more than make up for that decline in housing prices, which would cost buyers more per month while simultaneously meaning less profit for home sellers.

And just because price increases are cooling dramatically, Lance Lambert at Fast Company writes, doesn’t mean that home sales will increase. Lambert notes that Zillow is “predicting that the housing market will only see 4.1 million U.S. existing home sales in 2025. That would mark the third straight year of suppressed sales of existing homes.”

“For comparison, in pre-pandemic 2019, there were 5.3 million U.S. existing home sales,” Lambert writes. That toxic interplay between high mortgage rates and high prices means that the housing market isn’t expected to loosen up anytime soon.

It should be crystal clear to everyone at this point that the free market isn’t going to resolve the housing price crisis on its own. It’s going to take several levels of government intervention, from partnerships with private businesses to a robust public housing option, to rebuild the housing supply and to rebuild American confidence in housing stability.

This Week in Trickle-Down

The Trump Administration is reportedly ending the IRS Direct File program, which allowed Americans to calculate and file their taxes directly with the IRS for free, rather than paying exorbitant prices for private companies like H&R Block or Intuit’s TurboTax software to do taxes for you.

“President Donald Trump directed his health department on Tuesday to work with Congress on revamping a law that allows Medicare to negotiate prescription drug prices, seeking to introduce a change the pharmaceutical industry has lobbied for,” Reuters reports. “Drugmakers have been pushing to delay the timeline under which medications become eligible for price negotiations by four years for small molecule drugs, which are primarily pills and account for most medicines.”

NPR reports that Elon Musk’s so-called “Department of Government Efficiency may have accessed privileged union information when the team was supposedly searching the National Labor Review Board for inefficiencies: “technical staff members were alarmed about what DOGE engineers did when they were granted access, particularly when those staffers noticed a spike in data leaving the agency. It's possible that the data included sensitive information on unions, ongoing legal cases and corporate secrets — data that four labor law experts tell NPR should almost never leave the NLRB and that has nothing to do with making the government more efficient or cutting spending.”

Speaking of DOGE, the New York Times notes that “Musk has promised to cut $1 trillion from the next fiscal year’s federal budget by Sept. 30,” but “last week, he seemed to revise that goal down to $150 billion, which is where DOGE puts its estimated savings on its website.” Even if you believe Musk’s arbitrary slashing wiped out inefficiencies, it seems as though government was much more efficient than the trickle-downers claimed it was—nearly seven times more efficient, in fact.

This Week in Middle-Out

Ezra Klein wrote about the biggest regret of most Biden Administration staffers: They supported the right policies, but they didn’t deliver them fast enough. “Speed connects voters with the consequences of their votes,” Klein writes. “To survive, liberal democracy does not just need to deliver; it needs to deliver fast enough that voters know who to thank — or blame — for what they’re getting. Right now, it is delivering so slowly that the lines of accountability are confused.” This is a lesson that middle-out leaders must learn if they want to win voters over with their policies: You have to deliver results in a timeframe that is short enough that people connect you with the benefits you’re supporting.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Author Mark Dunkelman joins Nick and Goldy this week to talk about his book Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress and How to Bring It Back. They have a terrific conversation about why it feels like grand civic projects are so much harder to accomplish these days. They also explore how to bring big infrastructure and community ideas to life—without sacrificing the smart and important regulations that keep us all safe.

Closing Thoughts

It has been a particularly rough news week, with every day seemingly bringing a new horrific story of innocent people dragged from their communities and shipped to foreign prisons without due process. It feels as though the social and civic norms that have stood for my entire life are crumbling. We keep The Pitch focused on political economy, but I wanted to take a second to acknowledge the enormity of the crisis, and to remind you that if you feel lost and scared when you check the news every day, you are absolutely not alone.

I also wanted to call your attention to this thoughtful essay by David Dayen in the American Prospect that echoes some of the thoughts I’ve been having lately.

Dayen doesn’t sugarcoat the damage that the Trump Administration is causing to our most cherished institutions, both inside and outside of the borders of this nation. But that is just one political movement that is unfolding in America right now.

“It is simultaneously true that we’re seeing the most powerful authoritarian movement in American history and the rise of an emerging opposition that has the raw material to become even more powerful,” Dayen writes.

That opposition isn’t coming from within the walls of Congress, but the streets of America in red and blue states. Dayen explains that this week, “in Nampa, Idaho, an arena was filled to capacity to hear Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez talk about preventing oligarchy from taking hold in America. The day before, it was over 20,000 in Salt Lake City; before that, it was 36,000 in Los Angeles, 19 months before any national election that could change the balance of power in Washington.”

“A week earlier, around three million people took to the streets to register dissent against virtually everything the Trump administration is doing, from tariffs to renditions, from the destruction of government agencies to the attempt to memory-hole our history,” Dayen writes.

“People are finding the connection in being together, feeling like they must become part of something bigger than themselves if we are to emerge from what for many is an American nightmare,” he continues. “You certainly come across cynics who believe that this mass movement has no plan, no theory of taking powerful men down and stopping the slide into despotism.”

Those cynics, Dayen writes, forget “how mass publics can tip over dominoes that get larger forces in motion to act.”

The millions of people in cities and towns around the country who have spoken up against corruption and wealth inequality may not make the headlines of newspapers every day, but those people are out there. They’re protesting at town halls, and they’re making art to convince people to get rid of their Teslas to signal their disapproval of Musk’s dismantling of government agencies. All those people share a common belief, and with every major rally and event they’re making more steps toward coalescing around a common purpose and a way forward.

There is a lot of destruction happening in the federal government right now. Once that destruction stops (or is stopped), there will be a quest for a new way of doing things. Americans won’t be satisfied with a return to the New Deal or the neoliberal way of governance that got us into this mess in the first place. We’re seeing people in Idaho and Salt Lake City stand up to protest a government run by and for the wealthy few, and this rising coalition is going to want real solutions to these new problems.

That’s where we come in. The people who read this newsletter understand that there are other ways that governments and economies can run—ways that work out better for everyone. Every week, we’re thinking about how to design the economy in a way that serves the vast majority of Americans, including more people in both our economy and our democracy.

This is vital work, and I’m proud to be doing it with you.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach