Friends,

Labor Day weekend is always a great time to reflect on the state of labor in America. And this year, with its “Hot Labor Summer,” marks an especially important moment to think about the progress that American workers have made, and what benefits, wages, and other improvements newly empowered American workers, both unionized and un-unionized—might push for next.

Hot Labor Summer kicked off early this year, when railroad workers’ unions announced on April 20th that they had finally secured paid sick days for railroad workers. Railroad companies had previously threatened sick workers with termination for taking an unplanned afternoon off to visit the doctor, and the issue of scheduling dominated railroad labor negotiations throughout 2022.

Pundits accused the Biden Administration of selling workers out when they brokered a new contract which did not include paid sick days and Congress voted to impose that agreement without adding the sick days last November, but unions gave the president credit for continuing to negotiate on their behalf until their demands were met. “We’re thankful that the Biden administration played the long game on sick days and stuck with us for months after Congress imposed our updated national agreement,” [IBEW Railroad Department Director Al] Russo announced in April. “Without making a big show of it, Joe Biden and members of his administration in the Transportation and Labor departments have been working continuously to get guaranteed paid sick days for all railroad workers.”

The epicenter of labor actions then moved to Los Angeles. After decades of studio consolidation and Big Tech “disrupting” existing revenue models for TV shows and movies, Hollywood screenwriters went on strike, demanding that studios and streaming companies share viewer metrics, revise the now-outdated royalty system, and establish a clear set of rules for the use of artificial intelligence in writing screenplays for television and film.

Let’s be clear that these workers might not have had to strike if government had functioned as it should. Over the last 40 years, Congress has deregulated the TV and film industry, and trickle-down regulators from both parties allowed giant entertainment corporations to snap each other up and be bought in turn by multi-national conglomerates that put profits above sustainable practices like a living wage.

Not long after screenwriters took to the streets, over 100,000 actors joined the writers on picket lines—the first time in decades that both unions have struck together—and in addition to higher wages the Screen Actors Guild demanded that studios give up on their proposed plans to own the digitized rights to actors in perpetuity.

A SAG representative explained that actors were striking in part because studios “proposed that our background performers should be able to be scanned, get paid for one day's pay, and the company should be able to own that scan, that likeness, for the rest of eternity, on any project they want, with no consent and no compensation."

Show business isn’t the only LA industry to face a reckoning for its shoddy treatment of labor. Los Angeles hotel workers also demanded higher wages and affordable housing. Hotel and hospitality workers increasingly can’t afford to live in the cities where they work, and the 15,000 cleaners and service workers of UNITE HERE Local 11 quickly became a figurehead for an entire industry’s frustration with low wages. Thousands of LA municipal workers went on strike in early August to protest similarly low wages. And 85,000 healthcare professionals at California Kaiser Permanente facilities could be going on the biggest healthcare worker strike in American history in October unless their employers agree to demands including hiring more workers to meet the heavy patient load.

Hot Labor Summer also spread to Detroit, where auto unions were deep in negotiation with the three biggest car manufacturers in America. The workers argue that they deserve higher wages and better working conditions as their employers’ pivot to the manufacturing of electric vehicles Detroit auto workers were buoyed by an agreement between United Auto Workers and an Ohio battery manufacturer called Ultium Cells to raise worker pay by 20%. As auto manufacturers pivot from internal combustion engines to electric vehicles, the whole industry is pushing through a cloud of uncertainty; everything from gauging consumer demand to measuring the coverage of EV infrastructure around the country is still an inexact science. It makes sense for manufacturers to actually center the people who know the products—the workers—by raising their wages and encouraging them to stay on the job.

“Ultium said the interim wage increase will be retroactive, with active current hourly employees receiving back pay for every hour worked since Dec. 23, 2022,” writes Kalea Hall at the Detroit News, adding that “The UAW said in a statement that the ‘breakthrough agreement’ will raise wages by $3 to $4 an hour, adding it will continue to bargain for more wage increases.”

Auto manufacturers understand that their industry is on the cusp of revolutionary change, and they’re eager to rewrite the rules so that they can own a share of the prosperity this green new deal will produce. In Georgia, 1400 workers at a Blue Bird bus manufacturing plant that is currently set to produce electric school buses as part of President Biden’s green energy investments voted to unionize in May. Additionally, the Biden Administration is working to ensure that new manufacturing jobs in America will be high-quality, good-paying jobs, not the extractive lowest-common-denominator employment model that emerged during the trickle-down era.

While some strikes and negotiations are still ongoing, a few workers have already won significant gains. UPS, for instance, avoided a strike by more than 300,000 workers by agreeing to add air conditioning to delivery fans, eliminating forced overtime shifts on workers’ days off, and raising drivers’ total annual compensation to $170,000. And American Airlines pilots successfully negotiated a 46% increase in compensation and an impressive list of workplace protections just a couple weeks ago.

These unions are negotiating from a place of power right now. Unions are currently viewed positively by an eye-popping 71 percent of all Americans—the highest such approval rating since 1965—but union membership in America is still near an all-time low.

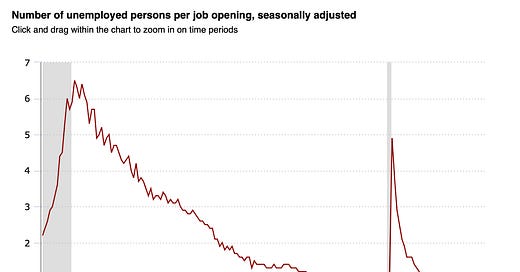

Still, even American workers who are not currently in a union possess more bargaining power than they’ve had for most of their lives. While the unemployment rate and job creation numbers are not quite as record-breaking as they were last year, unemployment is still near record lows and wages are finally climbing higher than prices. As the new monthly labor leverage ratio shows, workers have plenty of options, and most employers know it. There’s still more than one open job per unemployed worker, allowing people who are unsatisfied with their job to either negotiate for better pay or to find a better job elsewhere.

We talk a lot in this newsletter about the importance of growing the paychecks of American workers. And hourly wages are a vital metric—perhaps the most important single metric to gauge the health of the American economy. After all, those wages translate almost directly into consumer spending, and consumer demand is what spurs job creation.

But if you go back and scan all the above stories of union actions, you’ll likely find a common thread that unites these American workers: They’re not just motivated by wages. They also want to improve their workplaces.

Consider those hard-fought paid sick days that railroad employees kept fighting for, even after they won bigger paychecks last year. And Reuters noted that the agreement American Airlines reached with their pilots wasn’t just about dollar signs, either: “Quality-of-life improvements represent nearly 20% of the increased value of the new contract, the union said. For example, pilots would get premium pay if the company reassigns them from a trip they bid on, or have asked to fly.”

Those pilots aren’t alone in finding their current scheduling requirements to be untenable. As Big Tech has intervened in most parts of our daily lives over the past two decades, American workers have sacrificed a lot in the data-driven quest for workplace efficiency. Retail workers and restaurant employees in many states are subject to last-minute schedule changes that can see entire shifts wiped out, or the expectation that they come in to work a shift at the last minute.These workers risk getting fired by not responding to a “come to work” text from their bosses received at 4 am on their day off.

During the pandemic, many American workers received paid sick and family leave for the first time in their lives, only to lose that benefit when pandemic-era benefits were rolled back. Likewise, pandemic-era protections for affordable child care are disappearing and workers have been slow to return to the child care industry after lockdowns.

It’s fantastic that unions are leading the fight to reforming work to reflect the reality of life in the 21st century, and it’s huge news that the National Labor Relations Board just passed a new rule making it easier for workers to form a union—especially if they work for an employer who tries to illegally interfere with the union drive.

But most American workers are not in a union. That’s why we’re starting to see an array of policy prescriptions at the city, state, and federal level that address these problems for American workers.

Here in Seattle, Civic Ventures fought for and helped win Secure Scheduling legislation that requires large retailers and restaurant chains to pay more for last-minute schedule changes, and requires them to post schedules at least two weeks in advance. Some 1.8 million workers around the country are protected by similar “fair workweek” laws that allow employees to plan their lives and protect their free time.

The Biden Administration is working to lower childcare costs through funding requirements and other rulemaking methods that don’t require Congressional approval.

Private employers and a few state and local government offices are offering four-day, 32-hour workweeks at 40-hour payrates—an idea that appeals to a whopping 81% of full-time American workers.

The US still continues to fall behind most of the industrialized world by not having a federal paid sick and family leave law in place, but 17 states do have such laws on the books.

Various states and localities are finding ways to deliver the security of traditional work to gig economy workers, including a Seattle law that prevents sudden and inexplicable “deactivation” for gig workers, and a minimum wage for gig workers in New York City.

We’re also seeing a bigger push to pass stronger overtime protections for workers. The Biden Administration recently updated overtime rules to ensure that salaried employees paid up to $55,000 a year earn time-and-a-half for every hour over 40 hours they work in a week, and states are passing more robust protections that return overtime protections closer to historic levels. Washington state, for instance, recently implemented rules which, when fully phased in, will restore overtime protections to salaried employees paid up to 2.5 times the state minimum wage — a salary of about $81,000 a year. Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer says the American middle class was strongest when the federal overtime threshold was at its peak because it ensured that workers were either paid more for their time outside regular job hours, or they had more free time, or a mixture of both.

Cynics might dismiss policies like child care and scheduling as outside the realm of economics, but that would be a grave failure of imagination. At the bottom of it all, economics isn’t about money; it’s about people. And there’s more to middle-out economics than just spending money on goods and services.

Americans love to work, but we know that free time has value, too. People use their free time to engage in hobbies, to start small businesses, and to travel—all of which supports the economy. When parents can’t afford childcare, the lowest-earning adult has to leave the workforce to take care of the kids. When workers are forced to come in while sick, they risk the health of their customers, coworkers, and family.

And wages matter for more than just the workers getting the paychecks When workers are compensated poorly, that can create negative effects for everyone else, as when there aren’t enough air traffic controllers to keep national air traffic running safely and on time, or when a city can’t hire enough bus drivers to maintain enough coverage to get other workers to the office on time.

Next year, the White House, many Senate seats, and every single Congressional district will be up for a vote. This year, the American people are sending a message to those candidates: After the Great Recession and its intolerably slow recovery, followed by a global pandemic and its attendant inflation crisis, the workplace status quo simply isn’t enough anymore.

America needs a raise, to be sure. But Americans also want to write a new workplace contract that enables us to do our jobs to the best of our ability and to be the excellent parents, friends, and neighbors that we know we can be. When more of us can fully participate in the economy to the fullest—as workers, customers, neighbors, and citizens—that’s good news for everyone. The American people understand all this, and they will reward those candidates who promise to fight for them.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach