Friends,

“In stark contrast to prior decades, low-wage workers experienced dramatically fast real wage growth between 2019 and 2023,” write the Economic Policy Institute’s Elise Gould and Katherine deCourcy. This is a sharp reversal of the 40 years of growing income inequality we saw during the trickle-down economic era.

To refresh your memory: After World War II, American wage growth marched more or less in lockstep, with all Americans—regardless of wealth—earning higher wages as the American economy grew. But when Ronald Reagan ushered in the era of trickle-down economics, slashing taxes and regulations in order to line the pockets of the wealthy few, the wealth of the top 5% detached from everyone else and never looked back.

But then something amazing happened: In 2019, the numbers started to change. Over the last four years, the wage growth of the lowest-income ten percent of American workers began to skyrocket, while the top 10 percent stayed basically flat.

“The fast growth over the last four years, particularly for low-wage workers, didn’t happen by luck: It was largely the result of intentional policy decisions that addressed the pandemic and subsequent recession at the scale of the problem,” EPI notes.

Specifically, we saw that growth thanks to “enhanced and expanded unemployment insurance, economic impact payments, aid to states and localities, child tax credits, and temporary protection from eviction, among other measures” passed during the pandemic. “These measures also fed the surge in employment, which gave low-wage workers better job opportunities and leverage to see strong wage growth,” EPI writes.

Since so much of this growth is tied to pandemic-era programs that have long since lapsed, we’re not guaranteed to see these wage gains continue in coming years. And remember—we haven’t undone 40 years of consistent, systemic wage inequality through four years of gains. Just because we saw some impressive growth in a short amount of time doesn’t mean that it’s suddenly an easy thing for Americans to afford housing, food, and other necessities.

The most important lesson we can take from this data is that economic policies have tremendous effects on the everyday existence of Americans. Four decades of basically unchallenged trickle-down policies that enrich the wealthy few and extract wealth from everyone else had exactly the desired effect, hollowing out the middle class and leaving a few billionaires with more wealth than just about anyone in human history could imagine.

But because policy is a choice, we can also choose to use our policies to prioritize the broad majority of American workers, rather than the wealthy few. EPI argues that we can close the gap between the wages of the haves and the have-nots by increasing the minimum wage and making it easier for middle-class workers to unionize and bargain for better wages, among other policies. And best of all, everyone would win as working Americans supercharged the economy with their increased spending power, creating jobs and investing in their communities.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The State of the Economy: Housing Is Still Too Expensive

“Existing-home sales surged 9.5% in February to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 4.38 million, the largest monthly increase since February 2023,” writes the National Association of Realtors. However, even with that unexpected increase in existing-home sales, overall February home sales in the US “declined 3.3% from the previous year.”

Why aren’t Americans buying homes? Well, for one thing interest rates remain sky-high thanks to the Federal Reserve and mortgages now stand at 6.87%, which adds tens of thousands of dollars to the cost of a home over the lifespan of a 30-year fixed mortgage.

For another thing, home prices keep rising. NAR reports, “median existing-home sales price elevated 5.7% from February 2023 to $384,500 – the eighth consecutive month of year-over-year price gains.” As a result, “the inventory of unsold existing homes increased 5.9% from one month ago to 1.07 million at the end of February, or the equivalent of 2.9 months' supply at the current monthly sales pace.”

(It’s worth mentioning here that the housing market is flying in the face of the traditional Econ 101 argument that the market perfectly determines the correct price for every situation. An Econ 101 professor would claim that because people aren’t buying houses due to high prices, those prices would eventually come down. In reality prices keep climbing, contrary to the rules of supply and demand that we’re all taught in Econ 101.)

And remember, housing prices are one of the most consistent contributors to inflation in the United States right now, so it’s unlikely that we’ll get inflation fully under control until housing prices come down. The Fed doesn’t have a magic wand to fix this problem, but decreasing interest rates will go a long way to making the market more friendly to prospective buyers.

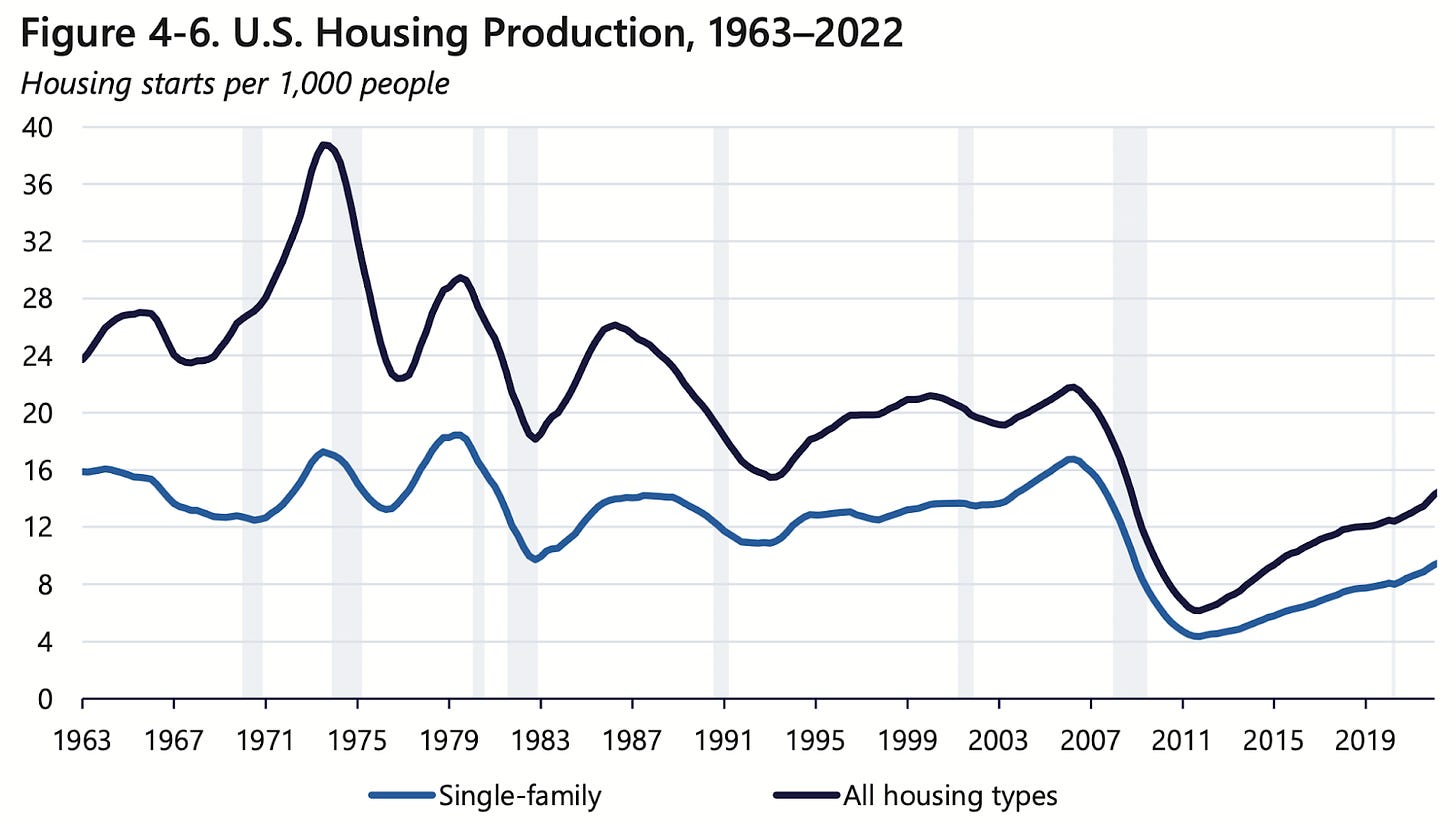

But as you can see in the chart below, we are simply not building enough housing to meet demand.

This chart is from a new report, released last week by the White House, which offers some solutions to fix this housing affordability crisis.

“The administration is backing a plan to pressure cities and other localities to relax zoning restrictions that in many cases hinder affordable housing construction,” reports the New York Times. The report also calls on construction firms to increase manufactured home production, which can be built at nearly half the cost of traditional housing, and suggests that increased government funding would address housing shortages in rural areas that don’t have as many resources for homebuilding.

“A quarter of tenants — about 12 million households — now spend more than half their income on rent,” the Times notes. “Prices are so high that if a minimum-wage employee worked 45 hours a week for a month, a median rent would consume every dollar he or she made.”

Those high housing prices could explain why consumers on the middle and lower portions of the income scale are slowing their spending down. Courtenay Brown at Axios reports, “Bank of America Institute recently analyzed card spending and found that after ‘being a point of strength during 2023, it appears that lower- and middle-income households' spending growth has been softening,’ though it remains in positive territory year over year.”

This also explains why so many consumers still report feeling so pinched by inflation. Since the Consumer Price Index assumes only about a third of Americans’ incomes should go to housing but the reality is that housing takes up a half of their income, so those larger wages we talked about in the introduction simply won’t go as far.

This isn’t a warning light yet, but it’s a sign we want to watch closely. Consumer spending, of course, is how the economy grows. Consumer demand creates jobs and increases investments in local communities. And while Courtenay notes that wealthy household spending is still riding high, there simply aren’t enough wealthy households to keep the economy growing at the pace we need it to grow. That’s why we aim our policies at growing the paychecks of all American workers—not just the few at the top.

Taking a Bite Out of Apple?

“The Justice Department and a group of state attorneys general filed a sweeping antitrust case against Apple on Thursday, accusing the $2.6 trillion company of violating antitrust law through its control of the iPhone, and raising costs for consumers, developers, artists and others,” writes Josh Sisco at Politico.

Readers who are old enough to remember the 1990s probably have some memory of the last major antitrust lawsuit of our lifetimes before the Biden Administration, which helped to loosen Microsoft’s tight grip on the personal computing market through its Windows operating system. That’s probably the closest analogy to this current move against Apple.

Given the widespread popularity of Apple products and general good feelings that consumers have about Apple as a brand, this lawsuit might not be as popular as similar current antitrust actions against, say the proposed Kroger-Albertsons merger. But when you drill down into the Justice Department’s charges, it certainly does look as though Apple is engaging in anti-competitive behavior.

“The main thrust of the case is how Apple intentionally locks consumers and developers into the iPhone ecosystem, by designing its products to not be interoperable, worsening the quality of consumer experience and throttling competition,” writes Luke Goldstein at The American Prospect.

Goldstein uses Apple’s CarPlay operating system as an example of the ubiquitousness of Apple’s reach. “Its system is projected to be installed in 97 percent of new vehicles, according to CarPlay’s own figures, and Apple has pursued a number of exclusive partnerships where it would be the default device in vehicles,” he writes, adding that this partnership has become so important to the Big 3 automakers that “auto companies have to adapt elements of their production to fit new iOS updates for CarPlay or other features Apple adds on.”

Essentially, Apple now has so much information about these cars and how they’re used that it could eventually compete with automakers on their own turf, or at the very least “collect the lion’s share of the profits on product sales, without needing to make the capital investments or manage the labor workforce.”

The New York Times notes that the case covers a wide spectrum of areas in which they argue that Apple is squelching competition: “smart watches, digital wallets, cloud-based gaming, messaging apps…and so-called “super apps” [like CarPlay] that bundle different programs.”

Naturally, a case like this is going to take a good long while to resolve, and there will be plenty of opportunities to discuss the importance of competition in the marketplace as we learn more about this lawsuit. This is sure to be a centerpiece of the antitrust discussion going forward.

Child Care Benefits Are Great for Employers, Too

We have made the case many times here that affordable child care is great for American workers. The pandemic clearly demonstrated that when parents don’t have access to child care providers they get less work done, they call out of work frequently, and many even leave the workforce entirely. Still, even though we saw firsthand the importance of childcare, only 12% of employers of full-time employees offer child care benefits—and that percentage is cut in half for part-time employees.

But a new study from Moms First and Boston Consulting Group takes a different approach to this argument. They’ve collected data at firms like UPS and Etsy which offer child care benefits, and they’ve found that child care benefits create positive results for employers, too.

“For every $1 spent on child care benefits, employers saw a net gain of between $0.90 and $4.25 through reduced absenteeism, less lateness, and lower rates of attrition,” writes Emily Peck at Axios. In other words, at a bare minimum, this report argues that child care benefits pay for themselves—and they may even be a source of greater profitability in terms of productivity and employee retention.

This is a smart study, because it’s framed in the tenets of middle-out economics. By proving that benefits for working Americans grow the economy for everyone, this study transforms how we think about child care—it’s not just a moral imperative, but a net good for everyone. Now let’s make it a reality.

Be Suspicious of AI Economic Claims

For Vox, economics and tech reporter Dylan Matthews explores how AI will change the American economy. If your jaw doesn’t drop when you read the claims in this paragraph, you might need to ask your doctor if you’re suffering from TMJ:

In 2020, the AI researcher Ajeya Cotra at grant maker Open Philanthropy released a report arguing that AI powerful enough to drive a surge in economic growth to 20 to 30 percent a year is coming, and more likely than not will emerge before 2100. The following year, her colleague Tom Davidson conducted a more in-depth investigation of the potential for AI to supercharge growth and concluded that per capita economic growth rates as high as 30 percent a year resulting from AI are plausible this century.

In fairness to Matthews, he does follow this astonishing paragraph with a clarifying point: “This is an extremely ‘big if true’ claim. Since good record-keeping began shortly after World War II, the US has averaged 3.2 percent economic growth per year. Since 2000, growth has been much more anemic, averaging 2.2 percent.”

But even including the above paragraph in a piece of reported analysis stretches the bounds of journalistic credulity. Giving an entire paragraph over to two claims that global economic growth will pop by an unprecedented 30% a year thanks to an unproven technology is the opposite of responsible journalism. Repeating their claims wholesale in a reputable, quality source of journalism like Vox allows disreputable AI companies to pull these quotes and use Vox’s journalistic reputation to attract investors and users to their products.

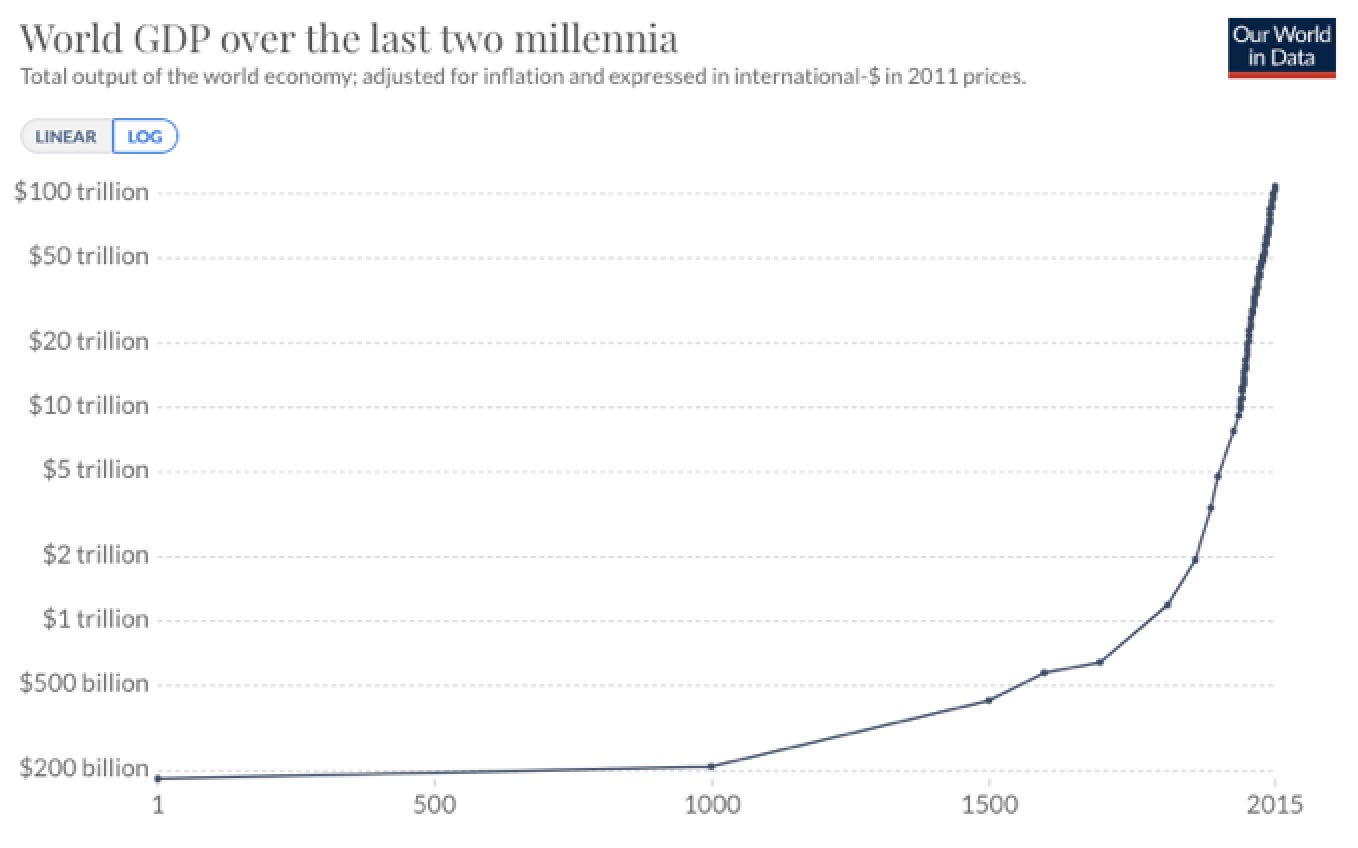

It’s even sketchier when you look at one of the reports Matthews quotes, which uses an eye-popping chart showing global economic growth going all the way back to 1 AD to justify their claims about the potential economic results of artificial intelligence:

Obviously, it’s too early for anyone to claim with any authority what the actual economic effects of artificial intelligence might be. But at this early stage, it’s best to keep a level head and assume that any outsize claims of a total transformation of our lives are hyperbole. Products like artificial intelligence need a strong base of evangelists in order to attract users and investors, and the evangelists are out there in force right now.

Which is not to say that the hype and concern swirling around artificial intelligence is entirely a bunch of hot air. Some people—mainly contract writers, marketers, and other people hired for piecemeal creative work—have already lost their jobs to artificial intelligence, and it’s very likely that we’ll see other shifts in our daily lives. But if the creation and proliferation of the internet in our lifetimes didn’t raise the global economic output by double digits, it seems unlikely that artificial intelligence will deliver double-digit growth. Let’s keep our wits about us and not buy the AI snake oil.

This Week in Middle Out

You’d generally expect the person you put in charge of managing your retirement funds to put your best interests first, wouldn’t you? Shockingly, Tara Siegel Bernard notes for the New York Times, that expectation “doesn’t generally apply, for example, when workers roll over their pile of money into an I.R.A. when they leave a job or retire from the work force.” That means a significant chunk of the population has handed their retirement over to people who aren’t legally required to prioritize their best interest: “Nearly 5.7 million people rolled $620 billion into I.R.A.s in 2020, according to the latest Internal Revenue Service data,” she writes. A new Biden proposal is working to close this ridiculous loophole, requiring virtually every professional who touches your retirement funds to try to get you the most out of your investment. (And in the Department of Elections Having Consequences: The Obama Administration passed a similar rule years ago, which the Trump Administration then reversed.)

The Biden Administration canceled another $5.8 billion in student debt for 78,000 public service workers last week. They’ve now canceled a total of $143.6 billion in student loan debt for nearly four million Americans over the past three years.

“Visa and Mastercard have agreed to cap the so-called swipe fees they charge to merchants that accept their credit cards, as part of a class-action settlement that could save merchants an estimated $30 billion over five years — the latest development in a nearly 20-year legal battle,” writes Tara Siegel-Bernard at the New York Times. The settlement plan, which caps and slightly rolls back swipe fees that merchants pay on each card transaction for the next five years, still has to be approved by a judge before the case is resolved.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

University of Massachusetts Amherst economist Arin Dube joins Nick and Goldy this week to talk about his remarkable new study which shows that the 40-year streak of growing income inequality that has disconnected the wealthy few from the rest of working Americans has finally reversed. (We discussed some similar findings in the introduction of this email.) Dube’s research shows that American paychecks have started growing again, particularly at the low end of the income scale. They discuss how this incredible change has occurred and how we can keep growing the paychecks of workers from the middle out and the bottom up.

Closing Thoughts

Last week, the Federal Trade Commission issued a report about the rising prices that Americans have been paying at grocery stores since 2021, concluding that “Some firms seem to have used rising costs as an opportunity to further hike prices to increase their profits, and profits remain elevated even as supply chain pressures have eased.”

We’ve been talking about greedflation in this newsletter for a couple of years, but the mainstream media has taken a long time to shift its coverage on the issue. Back when it first emerged, economists and pundits scoffed at the idea that corporations were taking advantage of price increases caused by supply chain disruptions by hiking prices even further and raking in record profits. They called the concept a “nonsense idea,” “demagogic rhetoric,” and a “myth.”

The FTC study, using publicly available data, “found that in the first three quarters of 2023, food and beverage retailer revenues reached 7 percent over total costs,” writes the New York Times’s Madeleine Ngo. “That was up from more than 6 percent in 2021 and the most recent peak of 5.6 percent in 2015.”

Arguments against the reality of greedflation were already crumbling as studies and expert analysis proved that grocery prices rose faster and longer than supply-chain disruptions, even as food manufacturers and grocery store profits rose much higher than normal. This very sober and deliberate FTC study should be the final nail in the coffin of the greedflation-deniers.

But the study goes even further than all the other recent studies, finding that greedflation itself was simply a symptom of an even greater problem in the grocery sector: “In its report, the F.T.C. concluded that supply chain disruptions did not affect companies equally across the grocery industry,” Ngo writes.

Corporate consolidation has killed competition in the grocery sector, and now a few big grocery chains are crowding out their much smaller competitors. This report makes another great case for the FTC’s recent challenge of Kroger’s acquisition of the Albertsons grocery chain.

If more grocery retailers were competing for customers in the sector, greedflation likely wouldn’t have tipped out of control the way that it did. When only a handful of giant corporations are responsible for a majority of the sales in a major sector of the economy, bad things start to happen for consumers. After 40 years, we finally have an administration in place that recognizes this economic truth, and governs accordingly.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach