Friends,

The biggest economic story in the country right now is the 1116-page tax bill that Republicans just passed through the House. President Trump was clear from the beginning about what he wanted House Republicans to pass—slashed taxes for the rich and powerful, slashed programs like Medicaid and SNAP for everyone else.

But due to the size of the bill and the fact that it was rushed through the final vote, we’re only just now getting a sense of what Republicans just sent to the Senate.

For the Washington Post, Catherine Rampell explains that this bill doesn’t just benefit the wealthy at the expense of the poor. It also robs from children to further enrich the old.

“Roughly 2 million children will lose food stamps under new work-hour-reporting requirements alone,” while many “more will probably lose at least some of their food assistance due to other measures, including some shifting more of the cost burden to states or forcing them to cut benefits,” Rampell writes.

The bill will also slash Medicaid, which Rampell points out provides healthcare to 1 in 5 Americans. “This matters to everyone on Medicaid, of course, but especially children, who disproportionately depend on public insurance and need adequate medical coverage in their early years to help them become healthy, productive adults,” she explains. “Today, roughly half of children in the United States are enrolled in Medicaid or its sister program, the Children’s Health Insurance Program.”

The bill also removes the child tax credit “from even U.S.-citizen kids if either of a child’s parents does not have a Social Security number,” Rampell explains. That means that if one of a child’s parents is a citizen and the other is here legally on a student visa, the parents would not be able to collect a child tax credit. This move, Rampell estimates, “would eliminate credits for 4.5 million children.”

Critics have been warning about the bill’s Medicaid and SNAP cuts for months, but there’s a lot more misery for working Americans hiding in the thousand-plus pages of the tax bill. One of the most under-covered aspects of the bill is that it slashes rental assistance programs by 40%. At a time in which housing prices are skyrocketing, nearly half of all renters are cost-burdened, and housing insecurity is growing in red and blue states alike, this is likely to be the policy that will turn the housing crisis into a catastrophe.

This week, two of the major economic modeling organizations—Penn Wharton at the University of Pennsylvania and the Congressional Budget Office—have finally released their models of what the Trump tax bill will mean for the economy. Remember that both of these models tend to use neoliberal economic assumptions about the economy that favor trickle-down economic policies over middle-out economics. (To learn more about these assumptions, read Nick Hanauer’s 2023 piece on the biases in these models.)

But even with those generous trickle-down biases in place, these models still warn that the Trump tax bill could result in economic disaster for working Americans, even as the wealthy few and corporations benefit. Penn Wharton’s model, for instance, flatly warns that the “average household in the lowest quintile – with a household income between $0 and $16,999 – would lose about $1,035” annually if the bill passes as written right now. The news isn’t much better for the next quintile: “incomes between $17,000 and $50,999 would lose $705 on average” per year. And those impacts are actually worse than what those dollar figures suggest—if you lose your Medicaid coverage, you can’t just earn and then spend $1,305 elsewhere to get new coverage. You simply no longer have healthcare.

By contrast, Penn Wharton estimates that families in the top 90-to-99.99% of the economy would take home $44,365 annually, while families in the top .01% would rake in an extra $389,280.

The Congressional Budget Office agrees with Penn Wharton’s assessment, noting in a letter to Congress [PDF] which “estimates that in general, resources would decrease for households in the lowest decile (tenth) of the income distribution, whereas resources would increase for households in the highest decile.” To be clear, that 4% increase in resources for the top decile is a huge amount of money, but it would have no measurable impact on the daily lives of the richest Americans. The lowest decile of Americans losing 4%, however, is a huge deal that would make their lives measurably worse on multiple levels.

And remember, these numbers are from very conservative analysis that uses trickle-down biases when measuring the tax bills. The reality is likely to be much worse than these models suggest. This is quite literally robbing from the poor to give to the rich, and if enacted, it’s likely to be the largest transfer of wealth from the poorest Americans to the wealthiest that any of us have seen in our lifetimes.

Even more damning, the tax bill would steal from everyone’s paycheck. Penn Wharton estimates that under the bill, the “average wage falls slightly in 10 years.” Remember, Penn Wharton doesn’t recognize the importance of the paychecks of working Americans in their economic model. In other words, it doesn’t understand that your paychecks are what create jobs in the economy, which means that it’s likely underestimating the economic damage that the tax bill will do to the economy by not recognizing the knock-on effects of slashing worker paychecks.

And finally, there’s an interesting observation in the Center for Economic Policy and Research’s analysis of the Trump tax bill that spotlights a segment of the economy that will do exceptionally well: Private equity firms.

When measuring a businesses’ earnings, the federal tax code currently, ”uses earnings before interest and taxes, or EBIT. But there is another measure that typically provides a much higher assessment of a business’ earnings,” CEPR notes. “That measure is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization are deducted, or EBITDA. The higher a company’s earnings, the more interest payments they can deduct.”

“For private equity, which is well-known for using high levels of debt when it buys out companies,” CEPR explains, “adding these two letters – DA – could raise tax deductions for the companies they own by up to 15 percent and boost the profits of those companies.”

“This is all very technical, but it is very important. This is a tax break estimated to be worth billions of dollars to the private equity industry,” CEPR concludes. “The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the addition of those two little letters will blow a $9.5 billion dollar hole in tax collections in 2025, and $73 billion from 2025 to 2034; Treasury has an even higher estimate of the 10-year hit to tax revenues of $179 billion.”

So not only does the Trump tax code that Republicans just pushed through the House steal from children to give to older Americans and steal from the poorest households to give to the wealthiest households—it also changes the tax code to give billions of dollars in advantages to the private equity firms that have been laying off hundreds of thousands of Americans, shuttering profitable businesses like Red Lobster, Toys R Us, and Joann Fabrics from coast to coast, and loading up businesses with debt while writing big checks for a handful of wealthy investors.

Trickle-downers love to argue that by directing the economy to invest in green energy and small businesses, middle-out politicians are unfairly putting government in the business of “picking winners and losers.” But that’s exactly what this tax bill does—it gives the rich and powerful a handout while robbing millions of Americans from meaningful investments that have successfully fought poverty and strengthened local communities around the nation.

The entire calculus of this tax bill couldn’t be any more trickle-down: If you’re rich, you’re a winner who deserves even more money, and if you’re poor you’re a loser who deserves to be punished. That’s been the economic law of the land for the last four decades, and Americans overwhelmingly don’t like the economy that trickle-down has created. Doubling down on trickle-down isn’t just bad economics—it’s also hugely unpopular.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Is the Labor Market Hiding Its Weaknesses?

Nitish Pahwa writes for Slate about the fact that even though unemployment data is still holding strong and economic signals suggest that the labor market is healthy, things are much harder for American workers than they may seem.

Pahwa acknowledges that “the topline numbers about the job market are, for all the chaos in America, pretty rosy.” But he warns that an “April 11 report from the think tank Employ America pointed out ‘the increasingly narrow scope of employment growth.’” Employ America found that while private health care and education job openings are still easy to find, “tech, finance, and manufacturing have either slowed their new job offerings or shed opportunities altogether.”

And those rosy numbers aren’t necessarily pointing in the right direction, either. “Across industries, the number of private sector jobs added last month was the lowest we’ve seen in a year. Overall hiring rates are at their lowest level since the pre-COVID era,” Pahwa writes. “Daniel Zhao, lead economist at the employer-reviews site Glassdoor, shared a company study from November that noted how ‘almost 2 in 3 professionals feel stuck in their careers’ thanks to job-market jitters.”

That’s bad news. Wages rise faster when workers know they have the option to find a higher-paying job in the same field. That competition between employers for the best workers is the true mark of a healthy labor market, and the numbers don’t indicate that many workers are benefitting from that competition right now.

“After the fallout from the Great Recession, when interest rates were low and companies began hiring rabidly, a typical line of advice was offered to America’s youth: Study a buzzy field in college, get early career experience while there, refine your credentials, and earn that degree—then, you’ll be guaranteed a comfortable, well-paying job with employers who feel lucky to have you,” Pahwa writes. “Or at least you’ll be able to pay for the basics and have a family in exchange for hard work. That promise has been, once again, deflating, even if it hasn’t fully collapsed … yet.”

Maybe that’s why we’re seeing another spate of labor actions, including the first transit worker strike in New Jersey since 1983, which came to a tentative conclusion this week when The Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen successfully negotiated a raise and better working conditions from New Jersey Transit.

Molly Liebergall looks at the transit worker strike and the recent Starbucks worker actions to protest new dress code requirements and asks if we’re about to see another “Hot Strike Summer” along the lines of the last two, with increased union activity and more workers standing up to demand higher wages and better working conditions.

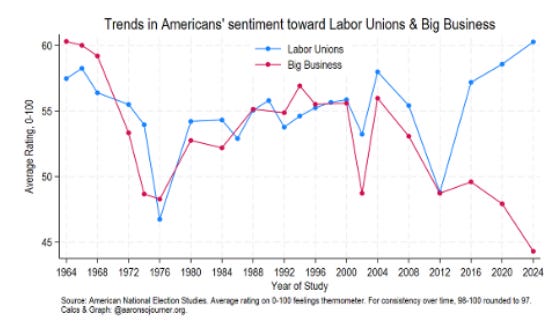

If unions do see increased activity this summer, they’re likely to see vast swaths of support from the American people. The Economic Policy Institute notes that according to new American National Election Studies data, “Americans feel more positively toward labor unions and more negatively toward big business than any time since ANES began asking the question in 1964.”

“Between 1964 and 2012, Americans’ sentiments toward labor unions and big business moved together, surging and dipping in tandem,” EPI notes:

Things started to change in 2012, when “Feelings toward big business stayed flat while feelings toward labor unions warmed to nearly a record high. In 2020, warmth toward labor unions kept climbing to a record high while sentiment toward big business fell to a record low,” EPI notes.

Now, ANES’s new data shows “that warmth toward labor unions climbed even higher while sentiment to big business fell even further, setting new records for warmth to labor unions and coolness to big business.”

Those favorable feelings toward union are basically shared among gender…

…and race:

EPI offers some good analysis about why these numbers have diverged so dramatically in the last decade or so. You see the support for unions rise dramatically along with the Fight for $15 and broader worker actions that took place at that time, which brought attention to how bad the working situation has gotten for workers on the lower end of the income scale. As more and more people spoke up about how wages and benefits declined even as CEO pay broke records, support for unions grew and support for big businesses fell.

But even though union favorability ratings are through the roof right now, union membership has actually declined over the same period. That’s because trickle-downers have continued to make it harder for workers to unionize.

Speaking as a former campaign manager, every time I see a sentiment survey surge up and to the right like these graphs do, I see a huge opportunity for candidates to make a splash by embracing public sentiment. There’s a lot of pro-worker territory for candidates up and down the ballot to plant a flag in by supporting legislation that makes it easier to unionize and by promising to grow worker paychecks while also restricting the unfettered power of big business.

The Trump Administration Says Your Personal Data Doesn’t Belong to You

Late last year, Wired reports, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau established a new regulation that would make it harder for data brokers to sell consumer information “including financial data, credit history, and Social Security numbers.”

“Data brokers operate within a multibillion-dollar industry built on the collection and sale of detailed personal information—often without individuals’ knowledge or consent,” Wired notes. “These companies create extensive profiles on nearly every American, including highly sensitive data such as precise location history, political affiliations, and religious beliefs.”

In these data-driven times, those profiles have become highly valuable. Without you even knowing they have the information in the first place, data brokers can then sell your information to anyone willing to pay the price, including marketers, financial institutions, and law enforcement.

Wired notes the CFPB quietly withdrew the regulation protecting your personal data “on Tuesday morning, publishing a notice in the Federal Register declaring the rule no longer ‘necessary or appropriate.’”

Wired reports that CFPB chair Russell Vought, the Project 2025 planner “who also serves as director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, received a letter on Monday from the Financial Technology Association (FTA) calling for the rule to be withdrawn.” The letter claimed that the rule “exceed[s] statutory authority” and “should be rescinded to restore regulatory clarity, fair competition, and an innovative landscape.”

The regulation protecting consumer data is exactly the kind of rule that the CFPB was established to create—it creates a level playing field for consumers against financial institutions that seek to exploit them, and it acts quickly to respond to rapid changes in technology. The elimination of the regulation is trickle-down at its worst—it takes your valuable information and hands it to the highest bidder, with no regulations put in place to prevent fraud or misuse.

Even worse, the sale of data also presents a grave national security risk. Wired notes that “data brokers have collected and made cheaply available information that can be used to reliably track the locations of American military and intelligence personnel overseas, including in and around sensitive installations where US nuclear weapons are reportedly stored.”

Americans Face Loan Troubles from All Sides

CNBC’s Diana Olick reports that “mortgage rates moved decidedly higher last week,” climbing “to 6.92% from 6.86%.”That might not sound like much, but it’s a big enough increase for potential homebuyers to balk. Olick says the increase “caused a 5.1% drop in mortgage applications compared with the previous week, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association’s seasonally adjusted index.”

“Homebuyers are seeing much more listings on the market than they did even a few months ago,” Olick notes, “but higher interest rates, as well as increasing concern over the state of the economy and inflation, have chilled the usually busy spring season.”

The economy is difficult right now for people with the resources and relative stability to buy a home, and things are worse for people who rely on buy-now-pay-later services like Klarna, which offers installment loans to people considering small purchases.

Klarna typically makes money on fees charged to retailers who offer the service, and on late fees from customers who don’t pay the company back on time. In recent months, Klarna is also expanding its reach, setting up arrangements with food delivery services that enable customers to basically buy burritos and groceries on layaway. But Quila Aquino reports at the Financial Times that Klarna is going through a rough patch that may indicate trouble for lower-income Americans. “On Monday [Klarna] reported a net loss of $99mn for the three months to March, up from $47mn a year earlier.”

The problem? Klarna’s “customer credit losses had risen to $136mn, a 17 per cent year-on-year increase.” Put simply, their customer base is not repaying their loans. Americans squeezed by price increases are turning to Klarna to buy these necessities and then finding that they can’t fulfill their commitment to repay the loans in a timely manner.

This is one of the most troubling signs for working Americans that we’ve seen yet. It indicates that the economic uncertainty we’ve seen in self-reporting consumer surveys over the past few months is starting to have real-world effects as necessities like housing and food become more costly to attain.

This Week in Trickle-Down

Democratic Colorado Governor Jared Polis has vowed to veto a bill that would make it easier for workers in his state to unionize.

“The Federal Reserve and two other agencies are expected as soon as next month to propose easing requirements for certain financial buffers that banks use to absorb losses,” writes Andrew Ackerman. Senator Elizabeth Warren protested the upcoming deregulation, saying that doing so would amount to “juicing shareholder payouts and executive bonuses while reducing money available for absorbing losses and lending to small businesses and households.”

This Week in Middle-Out

Vox offers a deep dive into the idea of quality child care legislation, examining what we mean by “quality.”

EPI celebrates several small steps toward paid parental leave laws that have been adopted in southern states.

The Center for American Progress explains how to bring commercial shipbuilding back to the United States.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

As the national conversation about the Trump tax bill heats up, we’re revisiting a conversation that Nick and Goldy had with federal tax policy expert Samantha Jacoby about the results of the first Trump Administration’s tax bill. Despite promises at the time that middle-class families would see many thousands of dollars in benefits from that tax bill, it turned out to be a massive giveaway for the wealthiest Americans and big corporations.

Closing Thoughts

“Moody's Ratings cut its credit rating on the United States by one notch on Friday, citing an increase in government debt and interest payment ratios,” reports Pete Gannon at Axios. “The Moody's downgrade to Aa1 removes the U.S. government's last remaining triple-A credit rating, diminishing its status as the world's highest-quality sovereign borrower.”

We don’t spend a lot of time talking about the debt and deficit here in The Pitch. Claims that “government budgets should be run like a household” and so should carry no debt are a classic trickle-down scare tactic that have been used to convince voters to act against their own self-interest time and time again.

In fact, debts are a perfectly healthy part of a nation’s economy—and also a healthy part of life for anyone with a household budget, as many families have car loans, home loans, and student loans. The late David Graeber’s excellent book on the subject, simply titled Debt, explains that debt has been an essential and important part of human history from the very beginning.

Most of the mainstream economic models, including the Penn Wharton and CBO models I discussed in the introduction, don’t have a nuanced enough understanding of debt. For instance, the Biden Administration’s investments in working Americans from 2021 through 2022 helped the American economy come roaring back from Covid.

Those investments paid for themselves with growing paychecks and an economy that grew faster than the rest of the world. If we had a less regressive, more middle-out friendly tax code in place, some of the economic growth that went to record corporate profits through greedflation would instead have gone to revenue that in part would have paid off some of the debt incurred to make those investments in the first place.

But the Trump tax bill generates an astounding amount of debt for a different purpose. The CBO estimates that it adds $3.8 trillion to the national deficit. There is no sane economic reason to incur that kind of debt simply so that the wealthiest .01% of the economy can take home an annual extra six figures in income, or so that corporations can pay less in taxes every year. A good simple rule of thumb is that incurring debt is necessary to inspire positive feedback loops that benefit everyone, while incurring debt to enrich a wealthy few even further only creates a negative feedback loop that harms everyone.

If you don’t believe me, you can listen to economists from the libertarian think tank The Cato Institute, who argue to Richard Rubin in the Wall Street Journal that “While Republicans were campaigning on reducing spending and controlling the growth in the debt, once they put pen to paper, their real priorities demonstrate that they care a lot more about cutting taxes.”

“Republicans often argue that deficits won’t actually climb if the bill passes,” Rubin explains. “They are counting on the bill’s tax cuts and Trump’s agenda of deregulation and oil-and-gas production to accelerate economic growth so much that extra tax revenue covers the costs.”

In other words, all that economic growth from deregulation and tax cuts will supposedly trickle down to everyone and fill the hole that they dug in budgets to pay for the tax cuts in the first place. The Cato Institute economist dismissed these claims by telling Rubin that “relying on economic growth has become the magic wand that Republicans are waving at any possible problem.” (Which is an especially problematic argument, given that Democratic presidents have reliably returned better economic growth than Republican presidents throughout the trickle-down era.)

The Moody’s re-evaluation of America’s debt matters in this moment because Republicans are about to add a whole lot more debt for no good reason at a time when international allies are looking at the shaky prospects for the American economy, our unnecessary and harmful campaign of tariffs, and the economic uncertainty created by President Trump since taking office and wondering if America is worth the investment right now.

We haven’t talked much in The Pitch about the troubled American bond market because it doesn’t have much of a direct impact on American workers, but it does signal a lack of faith in the future of the American economy. And the rising interest rates on government bonds are starting to contribute to already-high interest rates on loans like mortgages for Americans, as I noted elsewhere in this issue.

All of this is to say that the best thing we could do to help America’s standing in the international community is also the best thing we could do for the American economy: Drop the tax plan that enriches the wealthy few and instead rewrite the tax code and focus federal policy on investing in working Americans by raising wages and lowering costs.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach