The New Cost of American Inequality: $80 Trillion

The Pitch: Economic Update for Thursday, March 6th, 2025

Friends,

Five years ago, Nick Hanauer wrote about a remarkable report from the nonprofit research organization RAND that measured the growing income gap between working Americans and the wealthiest one percent.

For Time magazine, Nick explained that “had the more equitable income distributions of the three decades following World War II (1945 through 1974) merely held steady, the aggregate annual income of Americans earning below the 90th percentile would have been $2.5 trillion higher in the year 2018 alone.” Nick explained that sum of money is “an amount equal to nearly 12 percent of GDP—enough to more than double median income—enough to pay every single working American in the bottom nine deciles an additional $1,144 a month. Every month. Every single year.”

The report, Nick explained, “calculate[s] that the cumulative tab for our four-decade-long experiment in radical inequality had grown to over $47 trillion from 1975 through 2018. At a recent pace of about $2.5 trillion a year, that number we estimate crossed the $50 trillion mark by early 2020.”

“That’s $50 trillion that would have gone into the paychecks of working Americans had inequality held constant,” Nick concluded. “$50 trillion that would have built a far larger and more prosperous economy—$50 trillion that would have enabled the vast majority of Americans to enter this pandemic far more healthy, resilient, and financially secure.”

This week Carter C. Price at RAND updated the numbers in the report, and he found that the amount of money that the wealthiest Americans are sucking out of working people’s paychecks has not only increased, but the total amount of money has grown at an even-more-rapid clip.

In 2023 alone, Price found, the “bottom 90 percent of workers would have earned $3.9 trillion more” had inequality stayed the same as it was in the postwar period through 1975. And the total amount that the wealthy have sucked out of your paychecks has now grown “to the cumulative amount of $79 trillion.”

If it took 43 years for the inequality gap to grow to roughly $50 trillion dollars, how did the wealthy few add another $30 trillion to that inequality gap in just five years? Price offers three explanations:

The economy has grown,

Inflation has risen, and

The share of income going to the bottom 90 percent of workers has declined.

This is a lot to take in, but really the mechanics are pretty simple: The wealthiest 1% are raking in a lot more money than they used to, and they’re not paying taxes on their wealth. At the same time, the share of income of the bottom 90% of American workers has been more or less steadily declining since 1975.

Now, nine out of ten Americans only account for about 45% of total income. Put another way, 9/10ths of all Americans are making less income than the wealthiest 1/10th:

If you’re wondering why it seemed easier for previous generations of Americans to buy a home, pay for vacations, and generally manage the everyday expenses of running a household, the good news is that it’s not just your imagination. You are earning thousands per year less than equivalent American workers 50 years ago, and all that money didn’t just disappear—instead, it’s been hoarded by a tiny fraction of the population up at the tippy top of the economy.

This is the end result of almost 50 years of policy decisions made by trickle-down politicians—policies that kept the minimum wage low and diminished the overtime standard, while also making it harder for workers to unionize. These policies also slashed taxes on the super-rich and legalized stock buybacks, which allowed the wealthy few to funnel corporate profits directly into their personal wealth.

Make no mistake, it’s worse for our economy when that money is hoarded by the wealthiest one percent. Imagine the dynamic economy we’d be living in right now if that $80 trillion were circulating from our paychecks throughout our local communities, creating jobs and businesses.

It’s important to identify the factors of American inequality—how much was taken from workers and where it’s gone—because it helps to dimensionalize the size and scope of the problem, and to come up with policy solutions that meet the scale of this incredible drain on our economy.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Is Another Wave of Greedflation on the Horizon?

Obviously, the top economic story of the week is the 25% tariffs that the Trump Administration levied on Canada and Mexico. Yesterday afternoon, the Trump Administration announced a one-month delay on automotive tariffs, and more carveouts could be on the way if the stock market continues to respond with volatility.

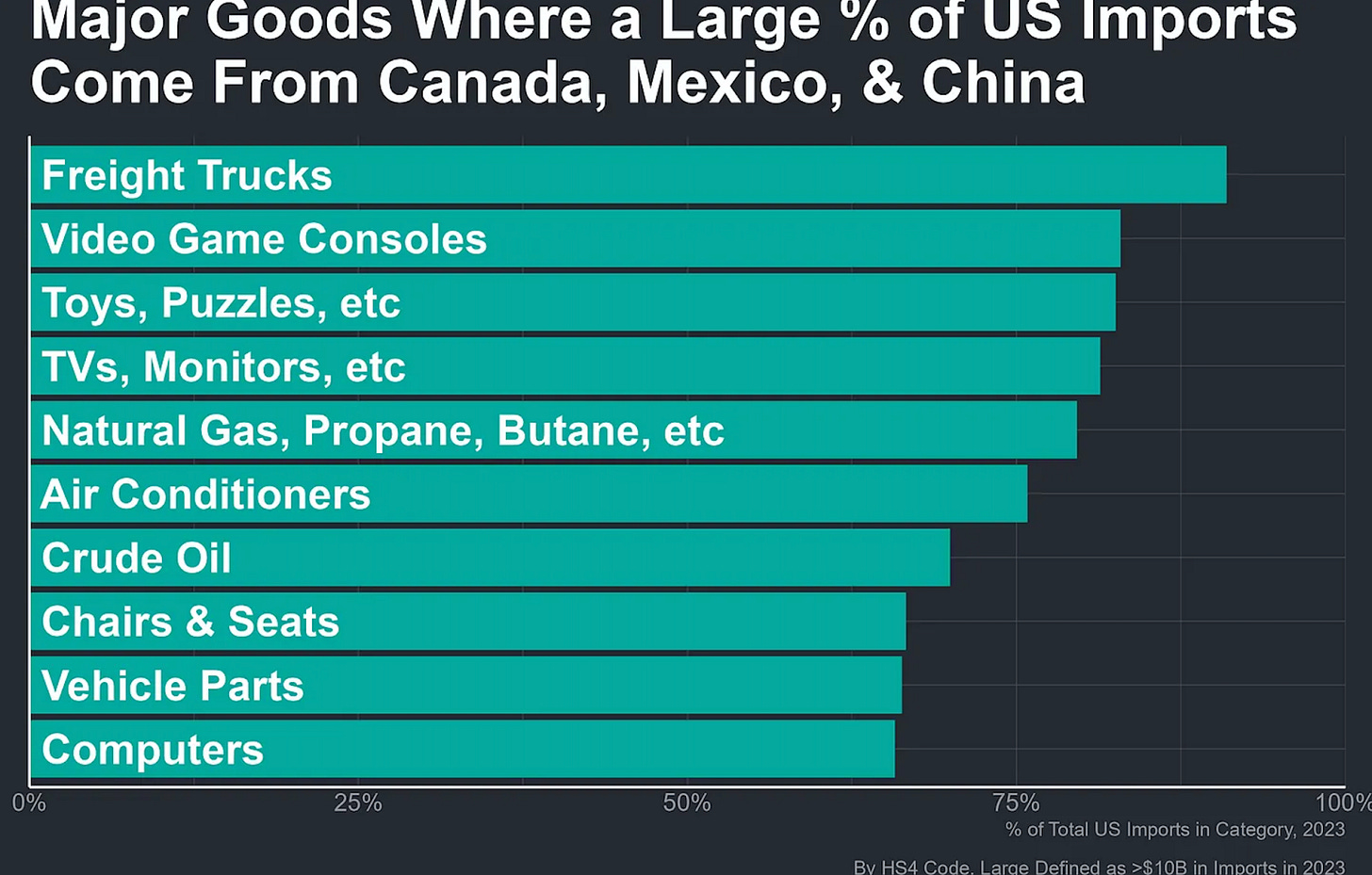

Apricitas Economics has put together an excellent post showing where consumers might expect to see immediate price increases if the tariffs do continue:

But whether the tariffs have been retracted or not by the time you read this, a considerable amount of damage has been done: The tariffs have introduced a whole new level of uncertainty into America’s economic reality. Businesses can’t predict what their products will cost several months in the future, our trading partners don’t know if they can rely on us to provide a steady stream of products, and American consumers don’t know how much they should budget for groceries, gas and other essentials .

On that last point, while fresh Navigator Research polling shows that Americans are divided roughly along partisan lines about whether the tariffs are a good idea or not, the most interesting result to me is that a huge majority of Americans—of every race and political persuasion—understand tariffs will raise prices for American consumers.

That number is important because the last time American corporations noticed that American consumers were expecting price increases—when broken supply chains came back online after pandemic shutdowns—they wasted no time raising their prices far above costs in order to pad their profit margins. Whether tariffs stick around or not, we could see another wave of greedflation emerging from this week’s confusion.

Profits from Those High Egg Prices Are Going Straight to Shareholder Pockets

Last week, I wrote about Cal-Maine, the largest producer and distributor of eggs in the United States. A report from business site Sherwood found that even as egg prices have skyrocketed, Cal-Maine’s profits have soared by almost 100% over this time last year. In other words, Cal-Maine sure seems to be using the bird flu as a pretext to raise egg prices far higher than their own costs, and pocketing the profits. This is exactly what Cal-Maine did during the last major bird flu outbreak, in 2023:

Now, according to Yahoo News, Cal-Maine is doing something with all those excess profits. Specifically, it’s handing $500 million of those profits to shareholders with no strings attached in a stock buyback scheme. Cal-Maine’s farmers or customers won’t see a penny of that half-billion dollars. It won’t result in bigger paychecks for egg producers, healthier conditions for chickens that would prevent future bird flu outbreaks, or cheaper eggs for Americans. Instead, that money will be used to buy back shares from people who own Cal-Maine stock. Only the wealthy few who can afford to hold large shares of stock—including, most likely, Cal-Maine’s CEO and executive board, who are probably compensated in part with stock—will see a big payday from this buyback.

If you want to learn more about stock buybacks, we at Civic Ventures have put together a free comic book explaining why they’re the most important mechanism for trickle-downers to suck that $80 trillion we discussed earlier from the pockets of American workers. I hope you’ll take a look and spread the word. Those buybacks play a key role in Cal-Maine’s actions, which have harmed consumers by raising egg prices much higher than costs and pocketing the difference.

The Economic Models Are Under Attack

Not only is the Trump Administration slashing jobs across the federal government right now, it appears that they’re also attacking the way we measure the health of the American economy.

“U.S. President Donald Trump's administration has disbanded two expert committees that worked with the government to produce economic statistics, potentially affecting the quality of data,” Reuters reported this week. An economist who worked on one of the committees explains that the committees “focused on continually improving economic data produced by the BLS as well as the Commerce Department's statistical agencies, the Census Bureau and Bureau of Economic Analysis.”

And Trump Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick floated the idea of stripping government spending out of the quarterly Gross Domestic Product metric. “You know that governments historically have messed with GDP,” Lutnick said on Fox News, “they count government spending as part of GDP. So I’m going to separate those two and make it transparent.”

First of all, it must be said that the Bureau of Economic Analysis already publishes all the GDP statistics with government spending listed as a component. You can see that reflected clearly in the most recent GDP report. So Lutnick is either unaware of the most basic facts of how the government reports GDP or he’s deliberately misleading the public to create outrage.

In any case, Lutnick is probably pushing for a change to the GDP because the indicator might soon start showing negative results for the Trump Administration. “On Monday, an economic growth model from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta forecast a steep decline for the first three months of this year — a 2.8 percent contraction in economic growth, after nearly three years of solid growth,” wrote Abha Bhattarai in the Washington Post.

Regular readers of The Pitch know that the GDP isn’t the best indicator of the health of the economy. Fifty years ago, when inequality was at its lowest in the modern era and CEOs “only” made 20 to 30 times the pay of their typical employees, GDP might have been a useful economic indicator. But now that CEOs make 344 times the pay of their typical workers, GDP is a better barometer of the economic health of the executive suites and corner offices than it is a measurement of how the average American family is doing.

But while GDP is a dangerously flawed economic metric, stripping government spending from GDP is an idea that would completely detach our understanding of the economy from reality. Ludnick is repeating the trickle-down fallacy that government spending is an inefficient drag on the economy, and that government jobs are inefficient compared to private-sector jobs.

Nick Hanauer wrote for the American Prospect that this trickle-down fallacy has been adopted at the highest levels of the federal government: “the Congressional Budget Office model assumes that all public investments are exactly half as productive as private investments. Public investments return 5 percent annually, while the same amount of private investment returns 10 percent,” Nick noted.

In fact, “it’s not even a little bit true. Think about health care. The U.S. government invests billions in basic research each year and is responsible for funding an incredible range of innovations, from mRNA vaccine technology to new antibiotics. Everyone benefits from this publicly funded research, sparking further innovations and benefits—much of it carried out by the private sector,” he adds.

Jared Bernstein explained in his excellent Substack that if Ludnick’s proposed change went into effect, “a public-school teacher’s output doesn’t count; a private-school teacher’s does. Same with a VA doctor, military cop, or state trooper (if the latter two were private security guards, their output would count).”

And Axios adds, “When the government buys a fighter jet, or builds a road, or educates a child, it reflects the production of goods and services. So if you exclude government spending from GDP, you aren't getting a full picture of U.S. output.”

Removing government spending from the GDP would effectively erase three million government employees from one of the major metrics that we use to measure the economy, and it would ignore all the investments in research, infrastructure, and the hard work of operating and maintaining a society that government makes every day in so many ways. In fact, while I suspect Lutnick is a trickle-down true believer who thinks that the government is an inefficient and wasteful investor, if he were to actually follow through on his threats to strip government spending from GDP, he would see exactly how indispensable government spending is to the daily functioning of the economy.

This Week in Trickle-Down

Speaking of interfering with economic metrics: Congressional Republicans are trying to enact a new economic measurement for their proposed tax plan that would obfuscate the plan’s harm to the economy, reports NBC News. “Extending the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which Trump signed into law in 2017, would cost $4.6 trillion over a decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office, the official nonpartisan scorekeeper,” NBC reports. “That’s under the ‘current law’ metric that has traditionally been used, as the tax cuts are slated to expire at the end of this year. But Senate Republicans want to use a different scoring method called the ‘current policy’ baseline, which would assume that extending tax cuts costs $0 because they’re already law.”

“Private companies added just 77,000 new workers for the month, well off the upwardly revised 186,000 in January and below the 148,000 estimate,” writes Jeff Cox at CNBC. “The report reflected tariff concerns, as a sector that lumps together trade, transportation and utility jobs saw a loss of 33,000 positions.”

“In Indiana, 16 and 17-year-olds can now work the same hours as adults and are no longer restricted by school hours and days,” reports More Perfect Union. “They also can work overnight without an adult and perform hazardous agriculture jobs. Many 14- and 15-year-olds can now work during school hours as well.”

“The quick math on the House budget shows a stark equation: the cost of extending tax cuts for households with incomes in the top 1 percent — $1.1 trillion through 2034 — equals roughly the same amount as the proposed potential cuts for health coverage under Medicaid and food assistance under the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP),” reports the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

This Week in Middle-Out

JV Calin at Daily Kos wrote a short, inspiring manifesto for the middle-out economic future in politics: “What if, instead of giving the top tier the money, we instead give it to the middle and lower class. Not as welfare, but instead, so they can create small businesses and farms,” they write. “So instead of the wealthy creating jobs, we let small businesses create the jobs. Instead of huge corporations creating dehumanizing jobs that only exploit workers, let us create small business jobs that will treat their employees like human beings and pay them more. Instead of wealth circulating at the top, let the wealth go instead to successful business owners in the middle. Instead of labor benefitting those at the top, let it benefit instead the middle and lower classes.”

I encourage you to check out the Economic Policy Institute’s revised tool that shows the cost of childcare in every US state. This is a useful way to visualize the expenses of child care for families across the economic spectrum, and it makes a great state-by-state case for affordable, quality childcare. Here is some data from Washington State, where the average annual cost of childcare is $20,677 per year or $1,723 per month.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Harvard economist David Deming joins the podcast this week to talk through his recent blockbuster article in The Atlantic, which argued that economists at a handful of elite universities—including Harvard—are stifling economic innovation and propping up a stale economic status quo. Deming calls this group “Big Econ,” and he argues that they serve as a monopoly, stifling economic innovation and making it nearly impossible for differing opinions to be heard.

Closing Thoughts

“For two decades, booming stock, housing, and private business markets have driven large capital gains in the United States,” says a new report from the Center on Equitable Growth. “Real capital gains, which are the inflation-adjusted appreciation of a financial or physical asset, have averaged 20 percent of national income over the past two decades, compared to 5 percent prior to 1980.”

“In 2021 alone, according to calculations using IRS and financial accounts data, capital gains totaled almost $6 trillion—a whopping 39.2 percent of national income,” the report continues.

Though capital gains make up a significant portion of our national income, the truth is that only a small fraction of the wealthiest Americans earn much of their wealth through profits from capital gains.

And it’s hard to measure and track the profits of capital gains, which means that most studies of American inequality fail to capture exactly how much wealth the richest Americans actually possess.

For instance, “only realized sales of assets are reported on tax forms since the United States only taxes capital gains upon realization—though not all realized sales are taxed (for example, taxes are deferred on the return to assets held in retirement accounts, and the first $250,000 of a gain from the sale of a primary home is exempted entirely,)” the report continues. “This means a large portion of total appreciation, or the sum of unrealized and realized capital gains, is unreported in these data.”

So how much capital gains wealth has gone unreported? The authors use IRS data to estimate that “between 1954 and 2021, $116 trillion in total capital gains were accrued, but less than 20 percent of that was reported on tax forms and subject to taxation.”

“We cannot say with certainty whether the remaining 80 percent of gains will ever be taxed in the future (e.g., if they are sold in taxable accounts at any point after 2021,)” they explain. “But much of these assets will likely escape taxation, thanks to avoidance strategies such as the so-called stepped-up basis rule that allows tax-free bequeaths of unsold stock to heirs.”

The report offers a staggering summation of how much of that wealth escapes taxation: “We find this results in an effective tax rate on real capital gains of 5.2 percent—significantly below the statutory rate of between 15 percent and 20 percent depending on income level.”

That’s a lot of revenue that could be invested in communities around the country but which instead winds up in the coffers of the wealthy few.

“Our paper suggests that the wealthy have long shielded capital gains from taxation and that raising substantial revenue from a capital gains tax would require closing certain loopholes in the tax code,” the authors write. “As tax policy debates occur throughout 2025 in the U.S. Congress, policymakers interested in raising revenue, reducing income inequality, and making the tax code more progressive should keep these implications in mind.”

At a time when the Trump Administration is reportedly planning on cutting the jobs of tens of thousands of IRS agents—effectively burning the agency to the ground—progressives have an opportunity to rethink taxation in America from the ground up. Two out of three Americans favor the idea of taxing the rich, and Trump’s slash-and-burn approach to wiping out the agency gives us an opportunity to reimagine how taxes should work in the 21st century, and then present our new ideas to the American people. Policies which recognize that wealthy Americans now collect a significant portion of their outsized wealth through capital gains, and which actually get that wealth circulating through the economy again, would be a winning proposition at the ballot box.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach