Friends,

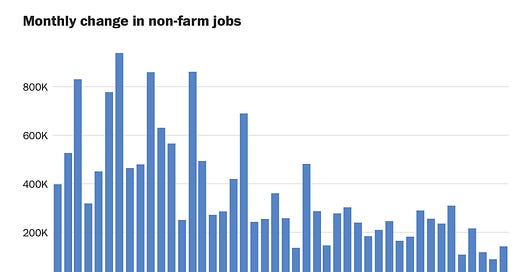

On Friday, the Department of Labor released the August jobs report, and the results showed continued slowing in job growth. The economy added 142,000 jobs, and the unemployment rate slightly ticked up to 4.2%.

On Twitter, Washington Post economics reporter Heather Long writes that even though the economy is still adding jobs, there are 7.1 million unemployed people in America now, compared to 6.3 million a year ago, and 161.4 million Americans employed versus 161.5 million a year ago. The Black unemployment rate has also risen to 6.1% from its all-time low of 4.8% in April of last year. The good news is that jobs are still being created, and wages have risen by 3.8% over the past year, almost a full percentage point more than the 2.9% inflation rate.

I’ve been writing for weeks that it’s time for the Federal Reserve to finally start lowering interest rates, and in aggregate, these numbers indicate that it is now long past time for the Fed to take action.

The weakening job market revealed in these latest figures is the direct result of the Fed’s intense campaign to raise interest rates over the past three years, ostensibly to combat inflation. The idea was that by making it more expensive to take out loans, employers would slow down growth and the economy would stall, which would bring prices back down. Some economists, including Obama economist Larry Summers, were calling for millions of Americans to lose their jobs, and the Fed seemed to agree with the idea that workers had to feel pain in order to bring the economy back to normal.

The problem is, that’s not how the economy actually works. Those price increases were the result of pandemic-era lockdowns—we broke global supply chains by turning the economy off and then turning it back on again. And then corporations took advantage of those price increases to raise prices even higher, far above their costs, and pocket the rest in the form of excess profits.

So now interest rates have been higher for longer than at any point in the 21st century. Those higher rates are making housing more expensive, they’re raising the rates on credit card debt, and—yes—they’ve resulted in a slowing job market.

Next week, the Fed gathers to discuss potential interest-rate cuts. Most mainstream economists believe that the Fed will only drop rates by a quarter of a percentage point. But because the job market is suffering right now, a growing number of economists and economic reporters are calling for the Fed to take stronger action and lower rates by half a percentage point. That includes Nobel laureate Joseph Stligliz, who argues that the Fed should make a big move because they raised rates “too far, too fast” which “put the economy at risk.”

I tend to agree with the Stiglitz camp.

The Fed’s three-year-long campaign to raise rates is clearly holding the American workforce down right now. Most other metrics—including rising wages, strong consumer spending, and an increasingly optimistic economic outlook from American consumers—point upward. By cleaning up their own mess, the Fed has a chance to return the job market to its full potential. And when workers are able to get good-paying jobs, that’s good for everyone in the economy.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Housing Is More Than a Matter of Interest

As I said above, lowering the interest rate will also make housing more affordable by lowering the cost of mortgages and making credit more affordable to ordinary Americans. But Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times explains that lowering the interest rate will not cure all of America’s housing woes.

“While the shift in central bank stance is already translating into somewhat lower mortgage rates in many countries, borrowing costs are not expected to fall back to the levels that prevailed during the 2010s,” Smialek writes. “Several economists said 30-year mortgage rates in the United States, for instance, could end up in the 5.5 to 6 percent range, down from their 7.5 percent peak last year but still up notably from the 4 percent that was normal before the pandemic.” What that will make it cheaper to get a mortgage, it won’t necessarily translate into more housing construction, nor will it get landlords to lower rents.

All the costs of building housing have also spiked in the last five years, and not enough housing is being built to fill that need. I recommend reading Smialek’s article because she makes it clear that housing affordability isn’t just an American problem—like the global pandemic, it’s a problem that is affecting virtually every nation in the developed world. And systematic problems like this often require multiple solutions and a lot of time to resolve.

One of the big problems with housing in America, economist Edward L. Glaeser writes for the New York Times, is local zoning limits—especially in the most desirable locations. “Areas with the most upward mobility limit building the most, which makes America more permanently unequal,” he writes.

Glaeser proposes withholding federal funds for local issues like transportation unless communities allow for lots of housing to be built. He explains that “the legislation could establish minimum construction levels over three years for all counties with median housing values above $500,000. States with high-price, low-construction counties would have to figure out how to overrule local zoning codes themselves or lose federal transportation funding.”

Direction of federal funding is not an unusual tactic. In the same way that the federal government threatened to withhold some transportation funding for states that didn’t raise the drinking age to 21, they can incentivize states and localities to reinvestigate their local housing policies in order to address the housing crisis that is making America unaffordable for too many workers.

Taking the Temperature of America’s Healthcare System

One of the best ways to measure the health of any nation’s economy might just be to examine its health care system. Americans famously pay more for health care than any other nation on earth, but many Americans are having a harder time than ever when it comes to accessing that health care.

Tina Reed at Axios cites a recent report that found “17% of patients had to wait one to three months for their latest doctor's appointment,” with particularly long wait lines for “neurology (26%), ear, nose, and throat (26%), psychiatry (20%), and OB/GYN (17%). Primary care stood at 19%.”

In general, 43% of respondents said they are waiting longer now for medical care than they were in the past. Anecdotally, many patients are reporting that they get less time per visit with their doctor, and Reed reports that “NYC Health + Hospitals recently told primary care doctors to cut appointment times in half to 20 minutes.”

Reed dubs this phenomenon “medical shrinkflation,” arguing that Americans are spending more for health care and receiving less medical care in return. Why are we seeing this now? “tens of thousands of doctors have left the field due to burnout and other factors, and surveys indicate even more plan to retire early,” Reed writes, adding that “Red tape around insurance and rising out-of-pocket costs are leaving patients frustrated and confused, and in some cases burdened by more medical debt.”

For Capital & Main, Mark Kreidler reports on another reason why Americans are seeing less return for their greater investment in medical care: Private equity firms are buying up hospitals and medical service providers, saddling them with debt, slashing budgets, and jacking up costs for patients.

Kreidler reports that the California state legislature considered a bill in February of this year that would have endowed the state attorney general with the power to investigate and even halt private-equity takeovers of businesses in the healthcare field.

I want to make sure that you read this list that Kreidler has compiled of the damage that private equity has caused in healthcare. It’s a sobering account of what profit-seeking at all costs can do to a field that should always place humanity over profit:

In the first two years after being taken over by private equity firms, hospitals on average are stripped of nearly 25% of their assets, including land, buildings and equipment.

Private equity investment in hospitals is associated with a 25% increase in patient falls and hospital-acquired conditions like blood poisoning (sepsis), as standards and quality of care decrease while staff sizes dwindle.

When private equity buys a doctor’s practice or a clinic, prices go up 20% and so do the number of visits, including big increases in follow-ups that often prove unnecessary.

The equity companies often dump the health care acquisition between three and seven years after buying, according to a watchdog group – or they allow the entity they bought and drained to fall into bankruptcy. The Private Equity Stakeholder Project found that 21% of the 80 large health care companies that filed for bankruptcy in the U.S. last year were owned by private equity firms. So far this year, the figure is 23%.

Thanks to the tireless lobbying efforts on behalf of the rich and powerful, the bill that was introduced in the California legislature in February has been stripped of much of its power. Amendments were added to the bill that would not allow the attorney general to examine private equity buyouts of privately owned hospitals, and it would carve out an exemption for dermatology clinics, which are a favorite target of private equity, but a diluted version of the bill could still be passed into law.

Healthcare is one of those fields that we talked about in last week’s Pitch, in which unrestrained trickle-down economics actively harms society as a whole. It’s why most other wealthy nations have enacted some form of government-run health insurance or single-payer health care programs—because we can’t allow the people who own our hospitals and doctor’s offices to prioritize quarterly profits over the health and well-being of their patients. (Notably, one of the common critiques from American politicians about national health care systems in other countries is that they are associated with long waits for care — which is exactly the negative outcome we are now seeing in the U.S. private for-profit system.)

We need government to advocate for people, and to make investments and regulations that ensure medical health professionals are able to make a good living while still providing excellent care for their communities. When it comes to healthcare, the free market doesn’t have your best interests at heart.

Meet the Low-Wage 100

The Institute for Policy Studies released their annual report on corporate executive excess, which spotlights the 100 companies with the highest inequality between the wealth in the corner office and the wages of employees.

“The 100 S&P 500 corporations with the lowest median wages — the Low-Wage 100 — last year paid their CEOs an average 538 times what they paid their most typical workers,” the IPS reports.

And while all these companies undoubtedly crow about their profits on quarterly earnings calls, the fact is that while low wages might look good in an earnings report, they’re bad for long-term economic growth: “Extreme pay disparities lower employee morale and productivity and raise turnover rates,” IPS writes. And wage disparities also stop workers from participating in the economy and reinforce long-standing racist and sexist systems by “widen[ing] gender and racial disparities, since women and people of color make up a disproportionately large share of low-wage workers and a tiny share of corporate leaders.”

The report is not all bad news. As we’ve seen in the broader economy, paychecks at the Low-Wage 100 have actually grown, with “the Low-Wage 100’s average median worker pay [increasing] by 9 percent, from $31,672 in 2022 to $34,522 in 2023.”

But the disparity is still immense. These companies all have the money to raise worker wages in order to address the disparity between executives and frontline workers. We know this because all but seven of the Low-Wage 100 have bought back shares of their own stock in the past five years, handing hundreds of billions of dollars in corporate profits away to shareholders with no strings attached.

Before the Reagan Administration, stock buybacks were illegal. In those days, corporations would have invested those profits back into the companies, raising worker wages and improving the customer service experience. But now, those profits are airlifted away from the company and put into the hands of investors—including CEOs and corporate executives, many of whom are compensated in stock.

What do these buybacks look like in practice? According to the report, over the last five years hardware chain Lowe’s was the worst offender, having “spent $42.6 billion on buying back its own shares, a sum large enough to have given each of the firm’s 285,000 global employees an annual $29,865 bonus for five years,” IPS reports. “In 2023, Lowe’s CEO Marvin Ellison enjoyed total compensation of $18.2 million. The retailer’s median annual worker pay: a mere $32,626.”

In second place is Lowe’s Rival Home Depot, which “spent $37.2 billion on share repurchases between 2019 and 2023. That outlay would have been enough to give each of Home Depot’s 463,100 global employees five annual $16,071 bonuses. Home Depot median pay stands at just $35,131,” IPS reports.

The report offers several common-sense solutions to end the huge disparity between the corner office and the warehouse floor, including taxing and regulating stock buybacks, tying a corporation’s tax rate directly to the pay gap between the CEO and the median employee’s wage, and directing government funds to companies with more equal pay structures, thereby incentivizing better behavior from businesses.

You can find the full IPS report (PDF) at this link.

What We Talk About When We Talk About Taxing Billionaires

Now that the wealth held by American billionaires has nearly doubled in the last seven years to $5.8 trillion—yes, with a “t”—we’re seeing more and more discussions about potential ways to tax that wealth.

Michael Linden of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth partnered with Elizabeth Pancotti to make the case for a so-called “Minimum Billionaire Tax,” which Vice President Kamala Harris has proposed on the campaign trail.

“When it comes to taxes, the ultrarich really are different and really are getting away with paying extremely low tax rates,” they write. “One recent analysis found that the average federal income tax rate for America’s 400 wealthiest families was only about 10 percent. That’s far lower than many middle-class families pay.”

Part of the problem is that billionaires don’t draw paychecks like working Americans do—their wealth comes from capital, which the authors describe as “owning an asset like a stock, a piece of property, or a business.” They explain that some 70 percent of billionaire income comes from the ownership of capital.

That wealth isn’t taxed in the same way that our paychecks are. That’s because “the tax on an increase in the value of a capital asset is only assessed when the asset is sold. And if that asset is passed on to an heir, the increase in value of that asset is never taxed at all,” they write, adding that “rich people can and do employ a range of techniques to reap the benefits of an increase in their net worth while avoiding selling their assets and thereby triggering the tax.”

That’s where the Billionaire Minimum Tax would kick in. “Under the proposal, anyone with at least $100 million in net worth (all ~10,000 of them) will have to pay a minimum of 25 percent in income taxes on all of their annual income, regardless of whether all of that income was ‘realized,’” Linden and Pancotti explain.

“This proposal would create a backstop against the ability of the superrich to avoid paying income taxes and ensure that, at a minimum, they are not allowed to pay lower real tax rates than middle-class families,” they conclude. “This is a commonsense and elegant solution (and one that even arch-conservative Art Laffer supported, not to mention 59 percent of voters).”

I urge you to read the full piece, which outlines the pros and cons of a Billionaire Minimum Tax. But also keep in mind that since this is unexplored territory, there are lots of different ideas being discussed. Because super-rich people often take loans against their capital, allowing them to spend their wealth while still owning their assets, some people believe that simply taxing those loans would be the most effective way to address billionaire wealth.

And for what it’s worth, Obama Administration economist Jason Furman has come out in favor of a tax on unrealized capital gains applied to people whose assets are valued at over $100 million. His recent discussion with Kyla Scanlon on the topic is a very approachable introduction to the problem of taxing wealth.

This is such an important public conversation. The more that Americans become aware of income inequality, and the more that Americans begin to understand the way billionaires accrue and grow their wealth, the more popular the idea of tax reform becomes.

When people understand how billionaire wealth functions, they realize that taxing the super-rich isn’t a matter of punishing anyone for success. I happily pay my share of taxes every year, and I want to make sure that billionaires pay their share, too. This is about rewriting the rules of the system to address how wealth really works in the year 2024. When we all pay into the tax system, we will all benefit from the investments that will follow.

This Week in Middle-Out

Esteemed labor economists Arin Dube and Ben Zipperer have published an important new meta-analysis which finds that “most studies to date suggest a fairly modest impact of minimum wages on jobs,” specifically that “only around 13 percent of the potential earnings gains from minimum wage increases are offset due to associated job losses.” Importantly, they find that “estimates published since 2010 tend to be closer to zero” — in other words, that newer research generally shows that raising wages does not eliminate any jobs at all.

A rising minimum wage also has positive impacts well outside what we think of as “the economy.” New research published in the journal Injury Prevention finds that higher wages may reduce firearm suicides. “A US $1.00 increase in a state’s minimum wage above the federal minimum wage was associated with a 1.4%…decrease in firearm suicides,” the authors write.

The economics section at the top of this week’s presidential debate was brief, but included a couple revealing quotes. Vice President Harris underscored her plans to support families and small businesses, emphasized her dedication to “lifting up the middle class and working people of America” and rejected the idea of “middle-class people paying for tax cuts for billionaires.” Meanwhile, former President Trump, in a rare moment of clarity, described his economic policy as “an open book” because “Everybody knows what I'm going to do. Cut taxes very substantially.”

Not many public policy priorities command supermajority support, so it’s worth noting that three in four Americans support a national paid family and medical leave program, according to Navigator Research, with 42% saying paid family and medical leave is “very important.” It would be tough to name another issue that has such good politics and such good economics.

Councilmember Girmay Zahilay of my own King County, Washington is proposing to tap $1 billion of unused county debt capacity to build publicly-owned middle-income housing. According to the plan, people of varying income levels “would live in the same buildings but pay rents on a sliding scale according to income.” The goal is for the housing to be “self-sustaining,” says Zahilay, because “the higher rents paid by the higher-income residents would help subsidize the lower rents paid by the lower-income residents as well as the ongoing operating costs.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

This week, economist Colin Mayer joins Nick & Goldy to discuss his new book, Capitalism and Crises. Mayer argues that the current profit-driven mindset of corporations tends to create crises, but that it’s possible to redirect corporations so they profit from solving human problems, instead of causing them.

Closing Thoughts

The Wall Street Journal’s Paul Kiernan looks into the numbers behind immigration. While immigration skyrocketed during the early part of President Biden’s time in office, it has dipped dramatically over the last year and is now approaching the highs of the Obama and George W. Bush presidencies.

“Immigration has lifted U.S. population growth to almost 1.2% a year, the highest since the early 1990s,” Kiernan writes. “Without it, the U.S. population would be growing 0.2% a year because of declining birthrates and would begin shrinking around 2040.”

Those immigrants are participating in the workforce. “Of recent immigrants age 16 or older, 68%—the participation rate—are either working or looking for a job, compared with 62% for U.S.-born Americans. In raw numbers, that likely amounts to more than five million people, equal to roughly 3% of the labor force,” Kiernan writes.

“Recent immigrants’ participation rate is likely to climb further in coming years. It often takes more than six months for someone who has entered the U.S. to receive a work permit,” he adds. “Labor-force participation for foreigners who arrived from 2004 through 2019 is a lofty 73%, according to census data.”

Recent immigrants are particularly likely to perform manual-labor jobs or to work in software development:

Bear in mind that these are largely fields that have been struck by waves of under-employment in the years after pandemic lockdowns ended—back when restaurants and stores had “nobody wants to work anymore” signs posted in their windows. And what’s more, all of those immigrants—including the undocumented immigrants—are paying taxes and buying food, clothes, and shelter in their local economies. They’re contributing a great deal to the economy, as well as contributing to our communities.

But in a time when one political party waved “Mass deportations now” signs at their convention, it’s important to think about what the economy might be like without a steady wave of immigration, and how the public life of our democracy might be affected.

For the New York Times, meat-packing industry journalist Ted Genoways reports that if Trump’s proposed mass deportations happened, the cost of food would skyrocket. “The fact is, America’s largest meat producers are dependent on the immigrants Mr. Trump is threatening to round up and deport,” Genoways writes.

“If he is elected and makes good on his promise to bar refugees, those producers could lose a vital source of labor overnight. If he succeeds in rescinding certain protections for asylum seekers and speeds the process of deportation trials, the entire industry could be brought to a halt. Meat processors are only just recovering from the ravages of the pandemic,” he adds. “This would push them to the breaking point — and perhaps crash the whole food system.”

We have a recent example of what that might look like, Genoways writes. “During the early stages of the pandemic, we got a glimpse of what happens during periods of even brief closings of packing houses: the destruction of livestock when there is no place for them to go, lost wages for workers and sales income for farmers, shortages in grocery stores and skyrocketing meat prices for consumers and devastating ripple effects for small towns already struggling to survive.”

The same would be true for fruits and vegetables and other farmed products, and any of the other fields illustrated on the graph above.

Many observers suggest that deporting millions of people simply isn’t practically possible. And while it’s a bit strange to debate the logistics of such a gruesome enterprise, it’s also true that simply issuing a credible threat of stepped up deportations could have significant economic effects. Perhaps most importantly, it would stoke fear among immigrant workers and their families, making them less inclined to challenge low wages or unsafe working conditions, and pushing them into the shadows of our communities.

Any practitioner of middle-out economics will tell you that immigration helps grow the economy and brings out the best of America. Welcoming people from all over the world is one of our super powers. Any president who calls for the mass deportation of 15 to 20 million people is actually calling for an economic disaster and will weaken America.

Be kind. Be brave. Onward and upward.

Zach