Friends,

“Historically, consumer attitudes regarding the economy have closely tracked prominent macroeconomic indicators like GDP, unemployment, equity prices, and inflation,” write researchers Ryan Cummings, Ben Harris, and Neale Mahone in a new report for Brookings. “But since the pandemic, this relationship has fundamentally changed. By most measures, consumer attitudes about the economy have been divorced from the underlying economic conditions, with consumers feeling as poorly about the economy as they did in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession.”

The relationship between how people currently feel about the economy and how the economy behaves seems to be fundamentally broken. As the Brookings report finds, the American people are spending even more since 2021 than experts predicted they would before the pandemic—and yes, that number is adjusted for inflation. People are behaving as though they believe the economy is strong, even though all the indicators say they believe the economy is terrible.

So what’s going on? For the excellent Substack newsletter Briefing Book, Ryan Cummings and Ernie Tedeschi look at some changes in the University of Michigan Survey of Consumer Sentiment, which is the gold standard measurement of consumer attitudes and is considered one of the fundamental metrics of American economic health by political and economic experts alike.

First, Briefing Book begins with the same question raised by Brookings:

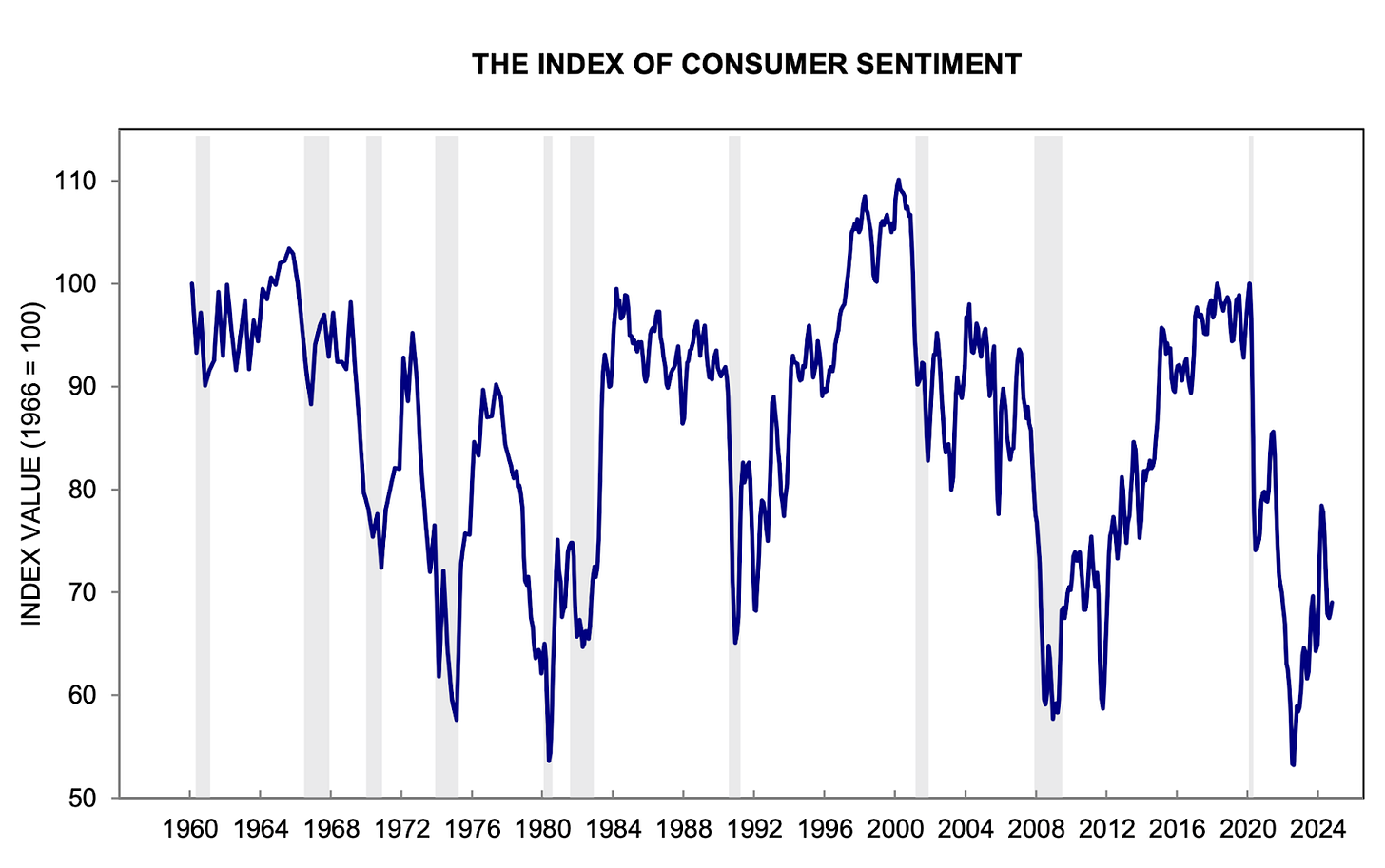

One of the enduring mysteries of the pandemic is, “Why are people so down on the economy when the underlying data are so strong?” In February 2020, the University of Michigan (“UMich” for the rest of this piece) index of consumer sentiment stood at 101, above the 90th percentile of the historical distribution. In October 2024, despite a low 4.1 percent unemployment rate, strong retail spending, and inflation that has largely returned to target, the index stands at 68.9, in the 15th percentile of the historical distribution and well below where we would predict given pre-pandemic relationships with key economic data. For reference, the index level is now lower than it was 15 years ago in September 2009, when the economy was barely emerging out of the recession brought on by the global financial crisis and the unemployment rate was 9.8 percent, more than double its current value.

Here’s UMichigan’s most recent chart of consumer sentiment over the last fifty years, which shows a huge dip in consumer sentiment during the pandemic, and another big slide when inflation skyrockets in late 2021 and 2022. That’s to be expected. But then, when you look all the way to the right of the chart toward the present day, the line, which was climbing steeply as price increases eased, began falling again.

So what’s happening here? The cost of housing is still unsustainably high, but it hasn’t skyrocketed in the past few months. Could it be partisanship in a tense election year?

We’ve talked in the past about the problem with self-reporting economic polls—in highly polarized times, people are much more likely to express dissatisfaction with the economy when the opposing party is in charge, regardless of their own personal economic health. That could be a factor.

But Briefing Book believes it has located a problem with the poll itself: “Due to the increasing costs of collecting surveys through the phone as well as a desire to ensure that the sample is representative, in April 2024 the UMich Survey of Consumers officially began incorporating responses from the web via a mailer that contained both a link and a QR code that would link a respondent to the survey.” Over the span of several months, the survey gradually incorporated more and more online respondents and gradually phased out responses collected from telephone surveys.

Briefing Book’s researchers find that “online respondents are dragging down sentiment primarily through more negative answers about conditions for durable goods and personal financial conditions.” In fact, “During the three month period from April-June 2024–when both online and phone responses were collected–the difference between online and phone respondents for these two questions are substantially large.”

That disparity means that “by June, online respondents were nearly 30 percent more negative in their assessment of buying conditions than phone respondents.” That’s not the only difference between phone surveys and online respondents. Those who fill out forms online are much more likely to choose “not applicable” options, which shows that they’re not engaging as thoroughly with the surveys online as phone respondents were.

Briefing Book’s analysis ultimately finds that UMichigan online survey respondents are likely to gauge the economy as 8.9 points worse than their phone respondents were. That 8.9 point difference exactly matches the difference between the UMichigan study and the Morning Consult survey of consumer sentiment that has developed since the new methodology went into effect. As you can see, both the Morning Consult survey and the 8.9-point-revised UMich survey track perfectly

Let’s be clear: This is not the unveiling of some conspiracy theory intended to throw the presidential race into doubt. It’s a wonky methodological problem caused by a necessary change in the collection process of a good-faith study that likely has knock-on effects on other polling models and political analysis. But even accidents made in good faith can have big repercussions. Perceptions of sentiment themselves affect sentiment, so if the survey is artificially low it could compound negative perceptions, creating actual lower sentiment data in the next survey.

But it’s also an important reminder that survey data can only get you so far when you’re trying to understand the world. It’s so important for smart people to question those assumptions and continually ensure that they’re not assessing the world through a lens that’s warped with bad data. It happens to everyone. This is something you should keep in mind when you’re doomscrolling through your favorite polling aggregator over the next week-and-a-half.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Existing-Home Sales Continue to Sink

“Sales of existing homes in the U.S. are on track for the worst year since 1995—for the second year in a row,” write Nicole Friedman and Gina Heeb at the Wall Street Journal.

“Existing-home sales in September fell 1% from the prior month to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 3.84 million, [the National Association of Realtors] said, the lowest monthly rate since October 2010,” they continue. “September sales fell 3.5% from a year earlier.”

The WSJ correctly identifies the reason for these record low sales: First, interest rates are still historically high, thanks to the Federal Reserve’s yearslong campaign of raising rates. And second, housing supply is drastically below where it needs to be—as in, we need millions of new homes to get back to where we need to be to meet demand. That low supply has concentrated the housing market and raised home prices and rents.

Also for the Journal, Ryan Dezember points out a silver lining in the dark cloud of housing. “More homeowners are borrowing against the rising value of their properties, suggesting that the worst of the remodeling slump has passed,” he writes. “The latest reading of a closely watched gauge of repair and renovation spending predicts a return to growth next summer. Spending should reach an annual rate of $477 billion by this time next year…That would approach the record annual rate of $487 billion reached a year ago, before high rates took a toll.”

The increase of interest in repair and renovation signals, at least, that consumers are thinking about big projects again. This is good news because it recognizes that spending is going strong and that consumers are feeling secure enough to plan for big purchases. It also suggests that people feel more comfortable taking out mid-sized loans again, and that if the Fed continues to lower interest rates perhaps mortgages will be within reach of a share of the population that has been frozen out by high rates.

Healthcare Giants Are Crushing the Little Guy

“Health insurance giants Cigna and Humana have rekindled merger talks that they had abandoned late last year,” reports Axios. “This would create a new titan in a health-care industry dominated by them, rivaling current insurance leaders UnitedHealth and Aetna.”

Axios theorizes that this merger might be on the front burner again due to headlines about election polling tightening up. “When Cigna and Humana talked merger last year, it was like waving a red handkerchief in front of Biden's antitrust regulators,” Axios notes. “But if Trump tops Harris next month, expectations are for much more lax oversight of corporate consolidation.”

You’d be hard-pressed to find an American who is enthusiastic about even more corporate consolidation in the healthcare sector, but that’s absolutely what would happen under a prospective second Trump administration.

The evidence that corporate consolidation is bad for healthcare is everywhere. For the New York Times, Reed Abelson and Rebecca Robbins explain how giant Pharmacy Benefit Managers, the middlemen who “employers and government programs hire to oversee prescription drug benefits, have been systematically underpaying small pharmacies, helping to drive hundreds out of business.”

Why would pharmacy benefit managers want pharmacies to shutter? “The pattern is benefiting the largest P.B.M.s, whose parent companies run their own competing pharmacies. When local drugstores fold, the benefit managers often scoop up their customers, according to dozens of patients and pharmacists.”

As a result, only three PBM firms—CVS, Optum Rx, and, here’s that name again, Cigna—handle nearly 80 percent of American prescriptions.

As we know, when there’s no competition in a market, prices rise. These three firms are more interested in achieving market dominance than in competing for consumers by aggressively lowering prices. We could expect to see more of the same rising prices and market concentration in the insurance sector if the Cigna/Humana merger were to go through.

The Economics World Compares Trump and Harris

For the New Yorker, John Cassidy looks into the economic repercussions of Donald Trump’s proposed policies, if they are enacted under a second Trump term. Economists believe, Cassidy writes, that “Trump’s policies would depress G.D.P. and employment growth, raise inflation, and bust the budget. Moody’s examined a Republican-sweep scenario, in which Trump permanently extends the 2017 G.O.P. tax cuts, carries out mass deportations, and imposes tariffs of ten per cent on all imports and sixty per cent on Chinese goods. Between 2024 and 2028, the analysis concluded, inflation-adjusted G.D.P. would grow at an annual rate of 1.3 per cent—much lower than the 2.8-percent annual rate seen since Joe Biden came to office.”

Cassidy continues, “Analysts at the Penn Wharton Budget Model fed Trump’s campaign promises into their computers and extended the outlook to ten years. They predicted a smaller impact, but it was still negative: by 2034, G.D.P. would be 0.4 per cent lower relative to baseline, and the amount of debt would rise by 9.3 per cent.”

Cassidy covers the outcomes of many different models, which test many of Trump’s proposed economic policies. So the results are understandably all over the map, though they all point downward for ordinary Americans.

Of course, Penn Wharton has been on the trickle-down side of many a study—their economic models are often biased toward the wealthy few over working Americans. In fact, it’s always worthwhile to investigate the assumptions behind any economic model before taking it as an article of faith. After all, the economic mainstream aggressively argued that President Biden’s middle-out economic agenda would hurt the economy, when in fact the exact opposite turned out to be true: America’s economic recovery from the pandemic beat out the rest of the world by a considerable margin.

But the sheer volume of Cassidy’s report—the fact that every single economic model agrees Harris’s policies would create growth, while Trump’s would hurt the economy—is worth taking into consideration. Unanimity is a compelling argument.

Only one thing would be certain under a Trump presidency: The wealthiest few Americans would get much richer. That explains why some of the richest men in Silicon Valley have come out hard in support for Trump.

Meanwhile, yesterday, 23 Nobel Prize-winning economists—that’s more than half of the living Nobel economic Laureates—published an open letter confirming that Vice President Harris’s economic platform would be “vastly better” for the American economy.

“While each of us has different views on the particulars of various economic policies, we believe that, overall, Harris’s economic agenda will improve our nation’s health, investment, sustainability, resilience, employment opportunities, and fairness and be vastly superior to the counterproductive economic agenda of Donald Trump,” the Laureates write.

They cite the Trump campaign’s proposed “high tariffs” and “regressive tax cuts for corporations and individuals,” which they say “will lead to higher prices, larger deficits, and greater inequality.”

“Simply put, Harris’s policies will result in a stronger economic performance, with economic growth that is more robust, more sustainable, and more equitable,” the Nobel winners write.

It’s easy to be flippant about this—23 winners of the Nobel Prize are not going to sway any undecided voters in Waukesha County, Wisconsin. But as an endorsement of a middle-out economic agenda that invests heavily in working Americans, it’s significant.

This letter can be viewed as a repudiation of trickle-down economics, and that’s a big deal in the economics world. After all, in 1986, the Nobel for economics went to James M. Buchanan, an architect of trickle-down policy who argued that “no self-respecting economist would claim that increases in the minimum wage increase employment.” And other avowed trickle-downers have won the prize in the years since.

But the pendulum has swung hard since those days, and today’s best economists have a much better understanding of how the economy actually grows—from the middle out, not the top down.

This Week in Middle Out

Last week, the Federal Trade Commission announced a new rule that would make it easier to cancel subscriptions. “The click to cancel part of the rule simply says that, if a consumer is in a subscription, it should be as easy to get out of the subscription as it was to get in,” an expert tells PBS.

The FTC has been busy. This week, they announced a new rule that bans fake product reviews online. The rule prohibits “the sale or purchase of fake reviews and allows the FTC to impose civil penalties on violators,” writes Samantha Kelly at CNET. “It also bans misleading testimonials, such as reviews generated by AI or written by individuals who have no actual experience with the business, its products or its services. In addition, the rule forbids the buying or selling of social media followers for commercial gain.”

The International Monetary Fund says that the American economy again leads the world after U.S. economic growth again exceeded expectations. The Economic Policy Institute looks into the economy’s strength in more detail.

Meanwhile, the Peterson Institute for International Economics celebrates the Biden Administration’s investments in American manufacturing.

And while the judicial branch continues to block the Biden Administration's broad student loan forgiveness programs, the White House recently celebrated a milestone of one million student loans forgiven for public service workers.

The Roosevelt Institute and the Center for American Progress look at the Biden Administration’s trade policies and uses them to formulate what a middle-out foreign trade agenda should look like.

Here’s an interesting policy that is on the rise in progressive states across the country: “New Mexico's state treasurer, Laura Montoya, tells Axios a new baby bonds program could be a ‘game changer’ and help erase economic gaps in her state, where about 75% of all children are born into families using Medicaid,” writes Russell Contreras. “Depending on what legislators decide, the state could start a child with $500 to $2,000 or more into a savings account at birth to be available after they turn 18, she says.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

This week, the Pitchfork Economics team is revisiting a 2023 episode about who benefits from automation. The insights from the episode—that wealthy people overwhelmingly profit from technological progress while most people’s economic status either stays flat or declines—are just as fresh today as they were last year. But the real reason we’re re-running this episode is to celebrate its guest: Daron Acemoglu, who last week won the Nobel Prize for Economics with two associates and this week signed on to the above-mentioned Nobel Laureate letter supporting Vice President Kamala Harris’s economic policies.

Closing Thoughts

Our friends at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy have put together a guide to the most important tax measures that voters will face on state ballots this Election Day.

As you might expect, the proposed measures range from progressive to regressive. Illinois voters could send a message to their leaders calling for the implementation of a 3% surtax on annual income over $1 million. Nevada voters could exempt diapers from the state sales tax, an exemption which has been approved by 19 other states.

And then there’s North Dakota, where “voters will decide whether to eliminate property taxes across the state,” ITEP notes. “In 2023, property taxes raised $1.4 billion a year in North Dakota to fund schools, libraries, emergency responders, and other services.” If passed, that measure “would force the state government to replace that lost property tax revenue, and there is no plan to raise new revenue at the state level to keep public services funded at current levels.”

I probably don’t need to tell you how disastrous a complete abolition of property taxes with no plan to replace lost revenue would be for a state, but the Tax Foundation has produced a level-headed look at the potential consequences of such a decision. And on a broader economic scale, without investments in families across the state, the North Dakota economy is likely to contract, creating a downward spiral.

Other states that have embraced trickle-down tax cuts are likely to suffer the consequences soon. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has published a report on the trend of automatic tax cuts, which states have adopted to be triggered after certain conditions have been met. “West Virginia is on track for an automatic 4 percent income tax cut in 2025, due to trigger provisions included in the state’s massive 2022 tax cut plan, and is now cutting further through legislation adopted during a special legislative session that just adjourned,” the Center writes. “Kentucky policymakers, who passed legislation that same year to phase out personal income taxes entirely, are already having to admit that the state's current financial outlook makes such plans untenable. And in Colorado, financial experts are warning about tight times ahead due, in part, to a series of triggered tax cuts on the horizon required by that state’s harmful set of tax and budget limits.”

These states are simply following the example of more than 40 years of trickle-down leadership on the federal level. Beginning with President Ronald Reagan, trickle-downers framed all taxation as a penalty on economic growth. If you cut taxes, they argued, the unfettered power of business would more than make up for the losses to revenue that followed. As we saw in the failed Kansas tax-cut experiment and as we’re seeing in Kentucky right now, those cuts actually result in widespread economic misery as families drop out of the economy and businesses lose customers.

In many ways the 2017 Trump tax plan, which cut taxes for corporations and the wealthy, was the ultimate trickle-down statement on taxes. “The legislation slashed corporate income taxes dramatically, from 35 percent to 21 percent,” notes Mother Jones. “ Not surprising, given that, according to the nonprofit Public Citizen, more than 7,000 lobbyists—on behalf of a who’s who of Corporate America—helped hammer out the bill’s details. That’s 13 lobbyists per lawmaker.”

And what did Trump’s tax plan deliver to the economy? It basically hyper accelerated the trickle-down tax plans of the past 40 years, delivering $50,000 per year to the richest 1% of all Americans, a much smaller $1500 raise to the wealthiest 10%, and virtually zero economic growth for everyone else.

It is time to change the conversation around taxes. Leaders need to embrace progressive taxes that grow the economy from the bottom up and the middle out. I found the Washington Center for Equitable Growth’s description of the three primary progressive tax mechanisms to be illuminating:

First, progressive taxes are a key tool for addressing and mitigating corrosive concentrations of wealth and income. Excessive inequality is itself a drag on growth. Because taxes can be used to reduce inequality, they can be designed to enhance inclusive growth.

Second, taxes generate revenue that can be used to fund growth-enhancing public investments, such as universal child care and the mitigation of climate change, and to reduce long-term fiscal risks. A lack of revenue, conversely, can lead to underinvestment and a riskier fiscal trajectory.

Third, taxes can directly shape markets and economic choices. They have largely been used to reinforce counterproductive behavior and reward the already-economically powerful, but they can instead incentivize pro-growth innovation and competition.

All three of those mechanisms are important because they invest revenue deeply into working Americans while helping direct the flow of markets in such a way that they improve outcomes for everyone—not just the wealthy few.

For decades, trickle-downers framed their opponents as unabashed fans of taxation. The truth is that taxation isn’t the end goal of policy—taxes are a mechanism that we can use to build the economy that we want to see in the world. The end result of trickle-down tax slashing has been a handful of impossibly wealthy centibillionaires and stagnating wealth for everyone else. Middle-out tax plans can result in economic growth for everyone and an economy that’s devoted to finding solutions to big problems like our housing crisis and climate change.

No matter what happens in this year’s election, one of our biggest resolutions for 2025 should be to change the way we talk about taxation, moving from a punitive trickle-down frame into a middle-out vocabulary that recognizes that taxes are one of the most important policy solutions for building a new middle-out economy that prioritizes working families over corner offices. If you want to learn more about how to think and talk about taxes in a middle-out way, I urge you to visit the Hub for Growth’s resource page, which offers a new perspective on middle-out taxation.

Onward and upward,

Zach