Friends,

The biggest economic story of the week is the United Auto Workers union strike. Late last week, UAW President Shawn Fain announced that the unions would follow what he calls a “Stand-Up Strike” strategy, in which union members walk off the job at strategic locations rather than one massive walkout across all UAW job sites. As I write this, UAW workers are striking at manufacturing plants owned by all three American car makers—a first in the history of the union.

Robert Kuttner’s explanation of the strategy—and the history behind Fain’s decision—is a must-read. He says the pop-up strike idea “conserves the strike fund, which would only last about 90 days if all workers were out,” enabling the UAW to strike for much longer than it would during a full walkout.

“Second, it also allows the union to inflict the most damage for the least cost by taking advantage of supply chain vulnerabilities,” Kuttner continues. “And third, management not knowing which plant will be struck keeps the companies off-balance.”

Fain is framing this strike as an important milestone in the fight against income inequality, “a battle of the working class against the rich, the haves versus the have-nots, the billionaire class against everybody else.” So it makes sense that he’s using a middle-out strike strategy which understands that workers know the weak spots of their organizations at least as well as than management does, because they have to work around those weak spots every day.

Coverage of the strike is already riddled with the same tired old trickle-down threats. The New York Times talked with a Chamber of Commerce rep who is supposedly—less than one week in!—already worried about “the long-term financial viability of these three companies” due to the strike, and another former union rep who frets over the Big Three auto manufacturers moving their business to Mexico. You can also expect a flurry of headlines warning of the “economic impact” of the strikes, which always account for the theoretical short-term impacts to corporate profits, but never account for the long-term benefits for workers—and through workers, to the local economy.

It’s important to recognize these concern-troll comments for what they are, and to put them in context. These automakers operate plants around the world—including in so-called “high-cost” areas like Canada and the European Union. And the auto sector is highly organized most everywhere it exists—except for in the American south.

And it’s silly to claim that this strike or the wage gains that unions are calling for threaten the livelihoods of this company when workers are simply asking for the same wage increases that management has given to themselves—especially when these companies have already raked in $21 billion in profits this year so far, and handed $5 billion of those profits away to shareholders in the form of stock buybacks this year.

At the end of this email I have a lot more to say about the political ramifications of this strike, but if you’re looking for an article that examines the strikes from a ground-level perspective, I highly recommend this Washington Post article by Lauren Kaori Gurley which interviews two striking UAW members. It puts the consequences of this strike into perspective, explaining how auto workers have been consistently undercut and undervalued for the past few decades.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The Federal Reserve Needs Corrective Lenses

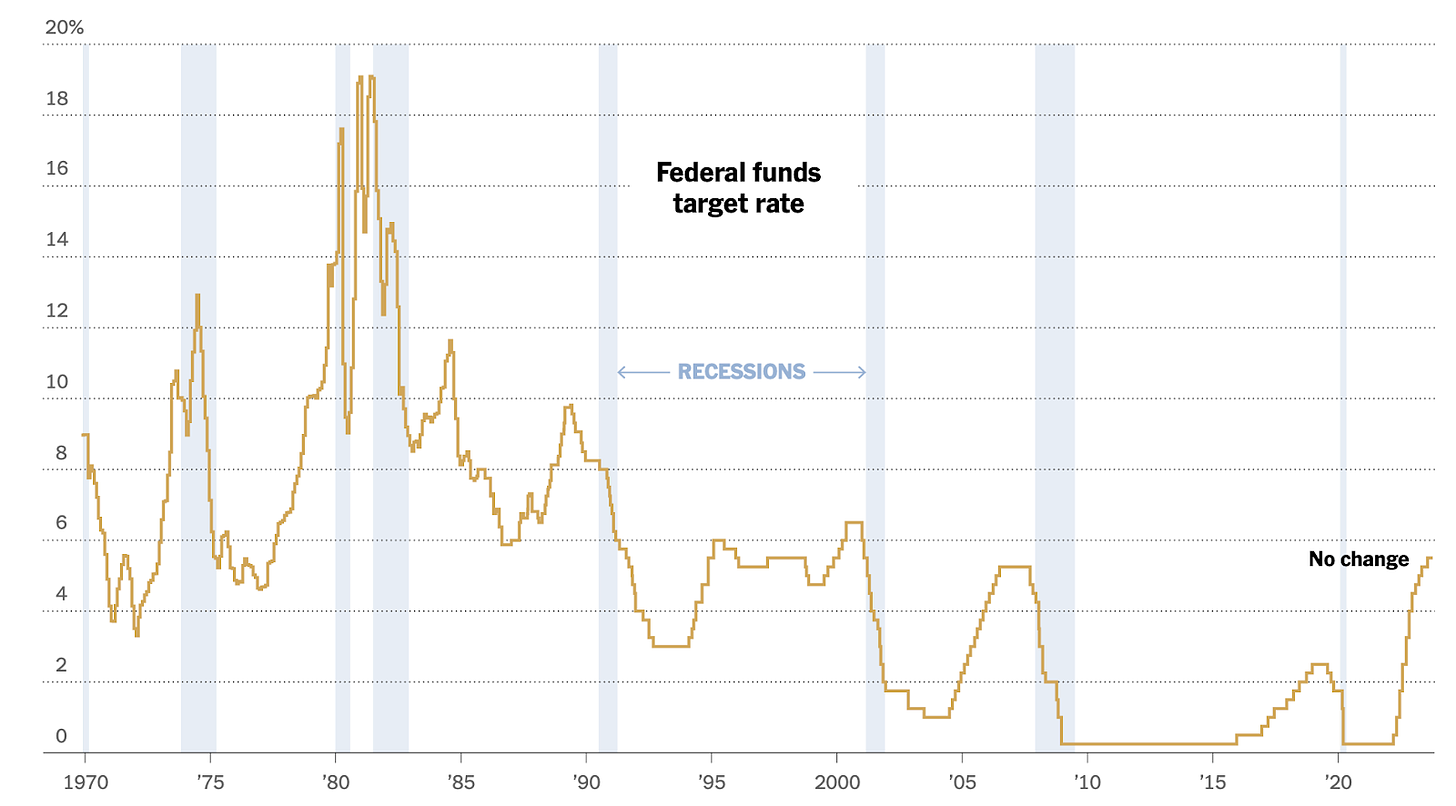

The Federal Reserve yesterday announced that they were leaving interest rates unchanged at 5.5% this month, but they expect at least one more interest-rate increase this year and they expect interest rates to remain high through 2025 or so.

The Fed remains generally optimistic about a so-called “soft landing” for the economy—meaning they expect inflation to die down without a recession—and in fact they’ve revised their expectations to be even more optimistic than in previous estimates. Ben Casselman writes, “The Fed sees inflation gradually returning to 2 percent over the next three years but without unemployment rising much above 4 percent. They expect growth to slow significantly but they don’t expect G.D.P. to contract (at least not over a full year).”

When taking Fed predictions in mind, though, you have to remember that very few of their predictions lately have played out as expected. When they started raising interest rates over a year ago, the Fed originally expected millions of Americans to lose their jobs by now. It’s pretty clear that they are not able to predict how the job market will respond to their policies with any degree of accuracy. But the millions of Americans who have seen their wages increase over the last two years should be grateful that the Fed’s predictions of mass layoffs were wrong.

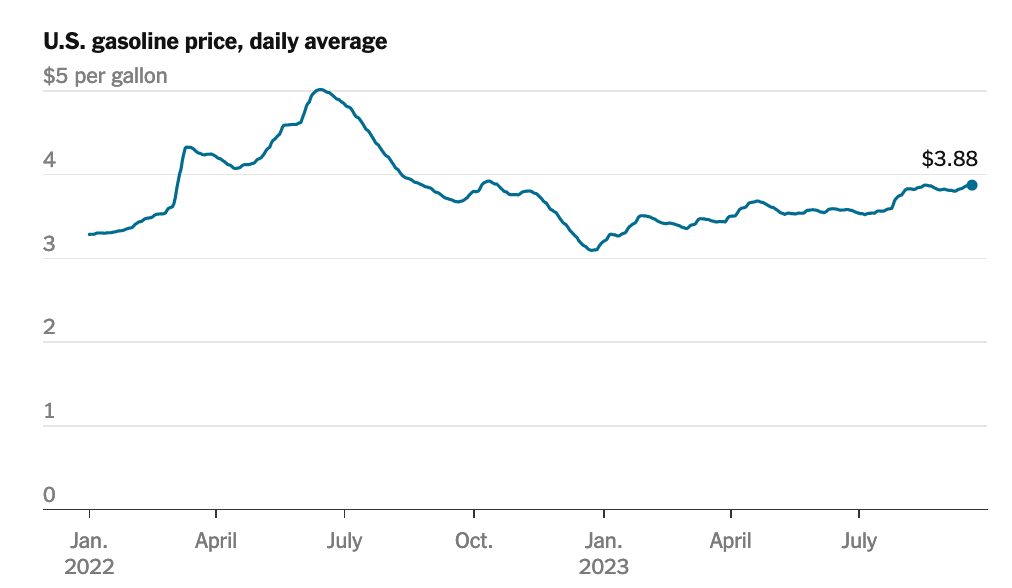

But while inflation has largely stayed flat in recent months, gas prices have slowly but surely risen almost 20 percent since the beginning of the year thanks to decreased Russian and Saudi oil production. Energy prices are a leading contributor to inflation, so these gas prices are a particular source of worry as the Fed considers their next move. Experts remain hopeful that those prices will decline over the next few months, though as we just noted above, expert economic predictions in general are a sucker’s game.

Mind the Gap

The Center for American Progress has analyzed last year’s Census data and come away with some pretty remarkable findings about the gender pay gap in America.

“Last year, women working full time, year-round earned a median income of $52,360, which was $9,990 less than the median income of men working full time, year-round, or 84 cents on the dollar,” CAP writes, and a 78-cent per dollar gap among part-time workers. That’s a significant decrease in the gender gap from even ten years ago, when the gap “was 77 cents on the dollar among full-time, year-round workers and 71 cents for all types of workers.”

So the gender pay gap is now the smallest it has ever been in American history, which is a remarkable sign of progress. But there’s still a long way to go, and the disparities grow even greater for women of color. “In 2022, Black and Hispanic women working full time, year-round typically earned 69 cents and 57 cents, respectively, for every dollar earned by their white, non-Hispanic male counterparts,” CAP writes, adding that “When accounting for all Black and Hispanic women working, they typically earned 66 cents and 52 cents, respectively, for every dollar earned by white, non-Hispanic men.”

Though the gap is shrinking, it still leaves a mammoth hole in the lifetime earnings of women, costing the average woman in a full-time year-round job almost 400,000 dollars over the course of her lifetime—and for a Black woman, that number almost totals a million dollars in lost wages compared to her white male counterpart.

When you look at the cumulative loss, it’s staggering. CAP writes “since 1967, the first year for which U.S. Census Bureau data on earnings by gender are available, working women have cumulatively lost $61 trillion in wages to the gender wage gap.”

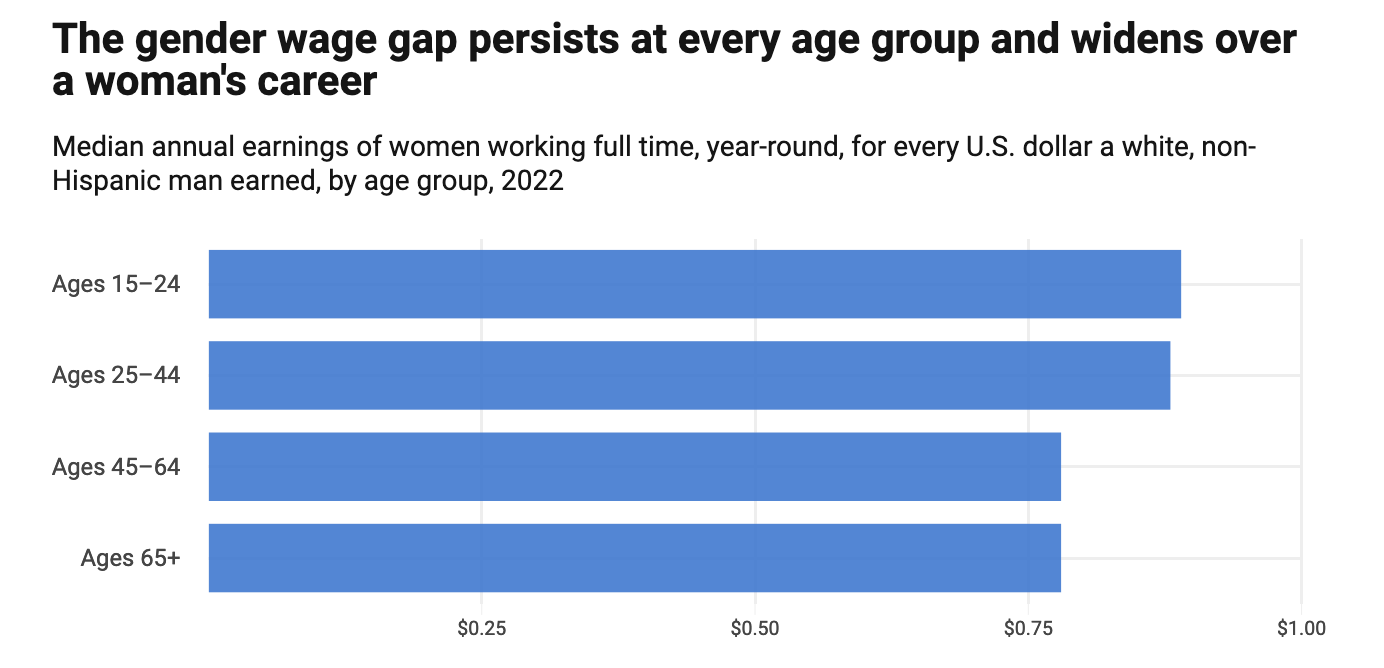

When these numbers are released every fall, a little cottage industry of trickle-downers pop up on the usual social media sites to claim that the gap is the result of women leaving the workforce to have children, as though that explains everything. First of all, women shouldn’t be economically penalized for having children—and countries with paid maternity leave and affordable childcare policies tend to do better at closing the gender pay gap—but second of all, even women entering the workforce for the very first time earn less than their male counterparts:

This pay gap is the result of institutional sexism and centuries of discrimination—but it’s been reinforced by specific policy choices that our leaders have made, and it can be undone by employing smart economic policies. We can take pride in the fact that the gap is now at its lowest level in history—that’s a sign that our policies are working—but we must also commit to finally closing the gender pay gap once and for all. We know how to do it, and many of the policies that can fix this problem—like affordable childcare and paid family leave—are tremendously popular. We just have to pass them into law.

Health Check: How’s the American Consumer Doing?

One of the central tenets of this newsletter is the middle-out economic understanding that working Americans create jobs with their consumer demand, not CEOs and the super-rich. But lately there have been several red flags that indicate there might be less of that consumer demand to circulate through local communities: Specifically, student loan payments are resuming, housing costs are still sky-high, and pandemic-era child care subsidies are ending this month.

Current indicators seem to show that consumer spending isn’t about to fall off a cliff. Brooke DiPalma writes at Yahoo Finance that “Over the holiday shopping season, which runs from Nov. 1 to Dec. 24, US retail sales excluding automotive are expected to rise by 3.7% from last year, according to the latest Mastercard SpendingPulse survey.”

The Mastercard survey tends to be fairly accurate. Last year, the same survey predicted a 7.1% holiday spending increase, falling short of the actual 7.6% result by just half a percentage-point. If this year’s predictions turn out to be within that range, holiday spending will be slightly above pre-pandemic levels.

While last year’s holiday season was all about goods, this year’s appears to be more about services. The survey predicts more Americans will be eating out during the holiday season, “with restaurant sales expected to grow 5.4%, more than the 3.9% growth expected for grocery sales.”

It’s fair to ask if people will just be floating this spending on credit cards—after all, US credit card debt just passed $1 trillion last month. In a tweet thread, Moody’s Analytics Chief Economist Mark Zandi calls that concern “misplaced.” He says that consumer borrowing was up earlier in 2023, but it has declined as inflation has leveled off throughout the year, and delinquency rates are still very low.

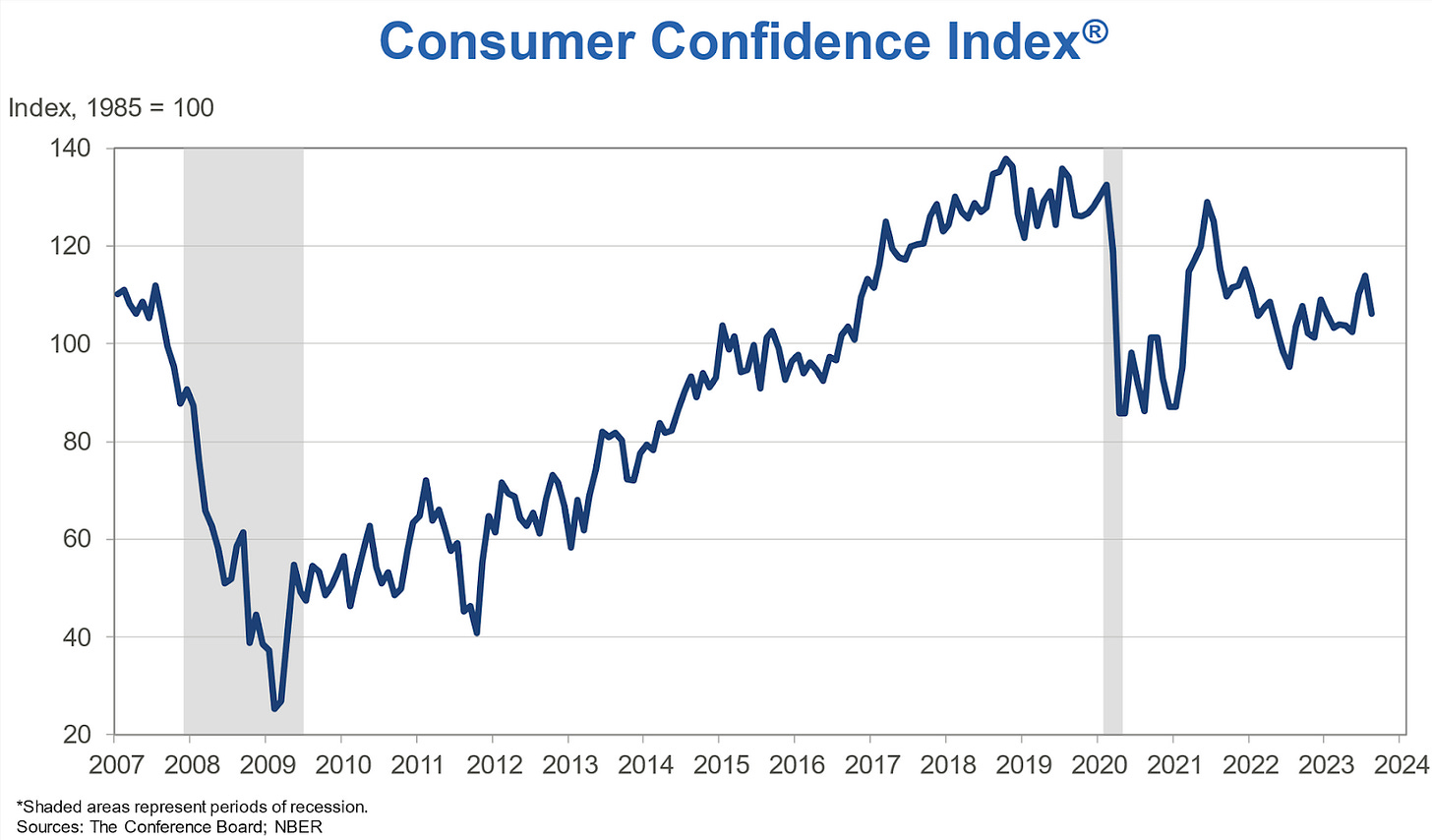

It’s important to stay vigilant for any economic warning signs that Americans are pulling back on spending. Consumer confidence did drop in August as Americans continue to face sticker shock from inflationary spikes and rising gas prices. But with wages growing higher than inflation for most of this year and that attendant consumer demand showing no signs of flagging, it appears that the American consumer is still hanging tough.

This Week in Middle-Out

Tim Wu wrote an editorial for the New York Times making the case that the judge in the Google antitrust case “should force Google to sell off its Chrome browser (which has a roughly 63 percent market share) and ban the company’s ‘pay for default’ deals with the operating systems for Apple and Android phones.” Doing so, Wu argues, will “effectively establish the rules governing tech competition for the next decade, including the battle over commercialized artificial intelligence, as well as newer technologies we cannot yet envision.”

The New York Times outlines the many ways banks are trying to lobby against new banking regulations which “would mark the completion of a process toward tighter bank oversight that started in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the beginning of the government’s regulatory response to a series of painful bank blowups this year.” The lines on this debate are very clearly drawn: On one side, you have giant financial institutions that want to be able to grow without any oversight, and on the other hand you have Americans that don’t want the economy to blow up every few years or so.

Lawmakers in Maine are trying to ensure that the state’s growing offshore wind-energy industry creates good-paying union jobs.

A new bill in California, if signed into law, would require large companies to be transparent about their carbon emissions: “By requiring businesses to provide the complete picture on their [greenhouse gas] profile, California is betting that market forces will put pressure on companies to cut down on their emissions.”

Jack Meserve at Vox explains the many ways that state programs “humiliate” single parents who apply for government support.“Depending on the state where they live, a single parent may have to agree to help the government recoup child support in order to receive child care assistance, food stamps, cash welfare, or Medicaid,” Meserve writes. “They may have to establish parenthood of their child, provide estimated dates and locations of conception, home or work addresses of the other parent, or even sign away their right to child support payments to the state.” We already know that middle-out policies which simply give money to parents nearly eliminates childhood poverty, but many states—not all of them conservative red states—continue to stigmatize single parents.

Until I read this Washington Center for Equitable Growth paper, I didn’t realize that fully a third of all mergers and acquisitions in America over the last two years were funded by private equity firms. That’s bad news for the American people because private equity tends to stripmine all the value from firms they acquire, leaving mass layoffs in their wake. The paper offers several tax solutions that will discourage this trend of vulture capitalism and raise important revenue for investments in the American people.

This Week on Pitchfork Economics

On this week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics, Maggie Goodlander from the Justice Department joins Nick and Goldy to explain the Biden Administration’s new proposed rules for mergers and acquisitions. The corporate consolidation we’ve seen over the past 40 years has killed competition, allowing big corporations to drive prices up and wages down, but the new rules would improve competition in the marketplace by making it harder for big corporations to buy each other.

Closing Thoughts

For the Washington Post, Jeff Stein explains that the United Auto Workers strike that began last Thursday is already becoming a litmus test for 2024 presidential candidates. In a break from his recent predecessors, President Biden has come out forcefully on the side of the auto manufacturing unions. “Over generations, autoworkers sacrificed so much to keep industry alive and strong,” Biden said. “The companies have made some significant offers, but I believe they should go further to ensure record corporate profits mean record contracts.”

As they usually do, the candidates at the back of the Republican pack responded by doing the opposite of what Joe Biden says. Senator Tim Scott was asked at a town hall event what he would do about the strike if he were president. He responded, “I think Ronald Reagan gave us a great example when federal employees decided they were going to strike. He said, ‘You strike, you’re fired.’ Simple concept to me, to the extent that we can use that once again.”

Nikki Haley took a similarly anti-union stance in an appearance on Fox News, calling Biden “the most pro-union president” and then saying "when you have a president that's constantly saying ‘go union, go union,’ this is what you get. The unions get emboldened, and then they start asking for things that companies have a tough time doing."

It’s certainly not a very wise choice to be so anti-worker at a time when national polls show support for labor unions is at its highest level in decades. That’s probably why Donald Trump is trying to thread the needle between appearing to support workers while also supporting the CEOs in the corner offices of those auto manufacturers.

“Trump is planning a rally in Detroit next week with union workers, including autoworkers, during the next GOP primary debate, although it is unclear if he will also visit the picket line,” Stein writes. But on Truth Social, which is his direct line to his most rabid fans, Trump took a very different tone by arguing instead that American auto manufacturers shouldn’t transition toward building electric vehicles, calling it a “disaster for both the United Auto Workers and the American Consumer,” and warning that “If this happens, the United Auto workers will be wiped out, along with all other auto workers in the United States.”

This is a pretty classic Trump riff: change the conversation and flood the zone with trickle-down fear-mongering about some oncoming disaster that only he can avert. Trump is trying to avoid talking about unions by shifting the topic to electric cars, insinuating that the unions wouldn’t need to strike if their bosses simply shifted back to manufacturing gas-guzzlers all the time. And while ensuring job security in the EV transition is absolutely a central reason for UAW to strike right now, Trump’s argument still makes no sense—it’s nostalgia for a lost past, plain and simple.

Stein says that Democratic leaders including Hakeem Jeffries and Ro Khanna have joined striking workers on UAW picket lines, and many on the left are arguing that President Biden should follow suit and join the protest. This seems like a smart idea, and one that would highlight a distinction between the middle-out economics of Biden and his Democratic predecessors. Despite his campaign promises, President Obama never joined a protest while in office.

And UAW leadership has made it clear that Trump is not welcome on their picket lines. Union President Shawn Fain issued a great statement explaining why: “Every fiber of our union is being poured into fighting the billionaire class and an economy that enriches people like Donald Trump at the expense of workers. We can’t keep electing billionaires and millionaires that don’t have any understanding what it is like to live paycheck to paycheck and struggle to get by and expecting them to solve the problems of the working class.”

Biden walking the picket line wouldn’t be a crass photo opportunity. It would send a powerful message that he’s on the side of workers in a way that nobody can question, and it would draw a clear distinction between Biden and his Republican opponent.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach