Friends,

I hope you had a relaxing holiday weekend. Every four years, the Labor Day weekend marks an important moment in presidential politics when talk transforms into action. It’s the time when volunteers begin flooding into neighborhoods around the country and campaigns gear up for mail-in voting to begin.

One of the most important questions that people must ask themselves before they vote is which candidate would prove to be better for the American worker. In the middle-out economic worldview, after all, working Americans are the most important part of the economy. It’s their spending—not the wealth of the few at the top of the income spectrum—that powers job creation, and so it’s in all of our best interests to make sure that paychecks are broadly growing.

The Biden White House understands this, which is why they released a report last week showing that “real compensation and incomes are up over the longer-term for American households. On a per-capita basis, from January 2021 to July 2024, real compensation, which includes the impact of both wage and job growth, is up 4.6% ($2,000), and real incomes, after taxes but before transfers, are up 4.9% ($2,300).”

The number is even more impressive if you go back a few months before the pandemic: Even when adjusted for inflation, workers earn $2,700 more per year than they were making in December 2019:

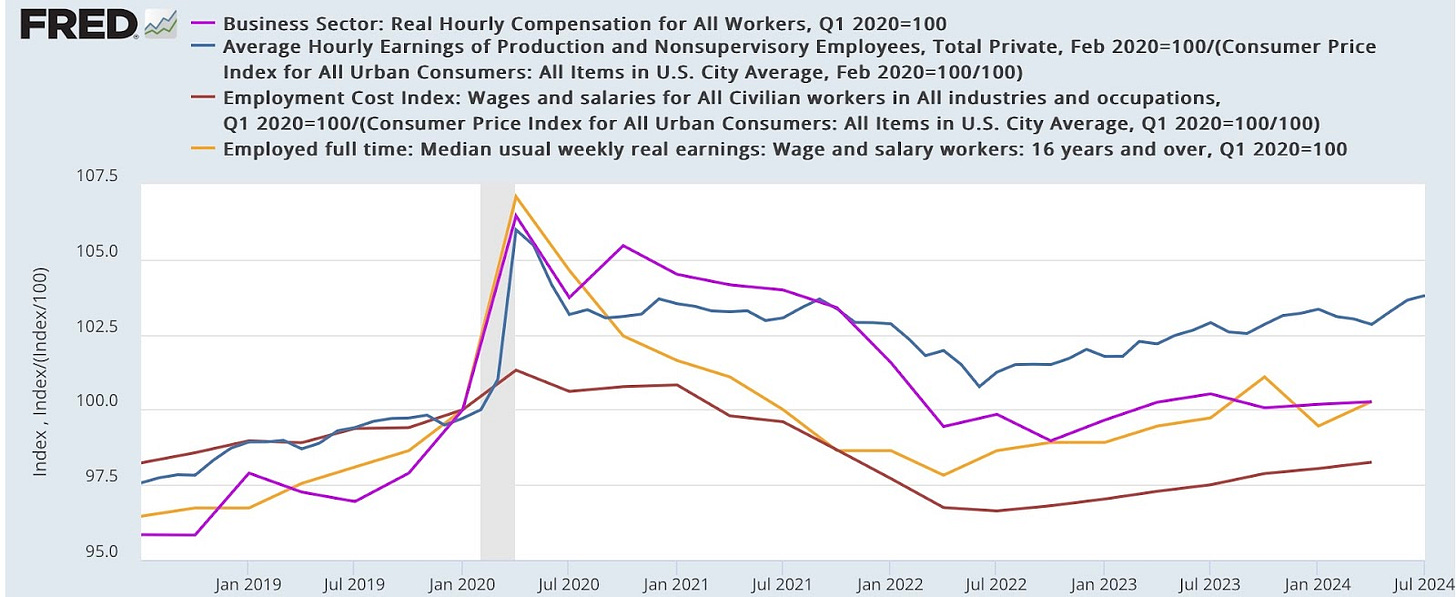

The Angry Bear blog celebrated Labor Day by measuring how much workers have gained since February 2022, which was when the economic recovery from Covid lockdowns began in earnest. They compared four metrics: Real hourly pay for workers; hourly pay for non-supervisory workers; the Employment Cost Index, which measures all salaried and hourly worker wages as well as the cost of benefits over time; and the median usual weekly real earnings of full-time employees.

“Of the four, only one – the Employment Cost Index – is below its pre-pandemic level, down -1.7%,” Angry Bear notes. “This is not nearly as negative as it may seem at first blush, since the boom in job availability meant that many workers switched jobs to higher paying occupations.” Since the ECI compiles the total cost of workers to employees over time, a spate of workers taking new jobs actually drives down the ECI, even though those workers are making more money at the new jobs.

So, since the recovery began, the data shows that “Real average hourly wages are up 3.8%. Real median usual weekly earnings and real hourly compensation are both up 0.3%.”

Even with inflation largely under control and paychecks rising, it’s hard for individual Americans to have a real sense of how the economy is behaving when prices have spiked by as much as we saw over the last three years. That’s why check-ins like these are important: They help to identify the fact that workers aren’t just making more than they were at the beginning of the pandemic or before inflation started spiking—their wages are bigger in real-world terms than they were in 2019, before the pandemic was on anyone’s radar.

That apples-to-apples comparison is a compelling one, but voters should always be asking what their leaders are going to do for them. That’s why it’s important to compare records of candidates up and down the ballot, to see not just the gains they’ve already made for workers, but their plans for what to do next. We’ll continue to look at policy proposals and head-to-head comparisons over the next two months here in The Pitch, and paychecks will always be the metric we prioritize when it comes to the American economy.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

From Coast to Coast, Hotel Workers Are on Strike

“Some 10,000 [hotel] workers, including housekeepers, front-desk staff and servers, went on strike across the United States on Sunday after contract negotiations stalled,” write Katie Robertson and Derek M. Norman at the New York Times. “On Monday, nearly 300 hotel workers joined the strike in Baltimore on the busy Labor Day holiday weekend.”

These strikes are unfolding in some of the biggest tourist destinations in the country, including Hawaii, San Diego, Boston, and Seattle. What’s especially interesting is that the striking workers are calling for improved working conditions, including the reinstatement of basic customer service expectations that have disappeared from the hotel industry over the past few years, in addition to pay raises. Specifically, they’re demanding that their employers finally end the staff and service cuts that the big hotel chains enacted during the early days of the pandemic. Most chains ended daily room cleaning for guests staying more than one night, for example, and the unions are calling for the reinstatement of daily housekeeping.

“A number of hotels have made those changes permanent to cut costs, offering daily housekeeping only on request,” the Times explains. “But some housekeepers say stripping away more frequent cleanings can make the cleaning at the end of stays much more arduous and time-consuming.”

Meanwhile, the International Longshoremen’s Association is considering a strike to protest the automation of their jobs at a gate entering a port in Mobile, Alabama. Peter Eavis reports that the union “had discovered that the gate was using technology to check and let in trucks without union workers, which it said violated its labor contract.”

Longshoremen have a particularly complicated relationship with automation. In the middle of the 20th century, unions negotiated the adoption of more efficient container ship technology in exchange for better-paying, higher-quality jobs. Chris Carlsson explains that the unions won an agreement that “saved shippers and the industry approximately $200 million during the 1960-66 contract period, and guaranteed longshoremen of that time wage increases, job security, increased benefits and pensions, and a large retirement bonus, equalling approximately $29 million in additional wealth for the workers,” although younger longshoremen were unhappy with the fact that the technology would eventually result in fewer available jobs.

These unions are confronting pervasive modern problems that millions of workers face right now—the automation of work and the slashing of customer-facing jobs in the retail and hospitality sectors. These are important fights as inflation continues to cool down and the economy faces a pivot point.

This is a great time for America to get a raise. Even the most trickle-down pollsters are finding that Americans are starting to feel good about the economy. Justin Lahart and Rachel Wolfe report that “When The Wall Street Journal asked 1,500 voters in late August for their feelings about the economy, 34% said it is improving, up from 26% in early July. The share who thought the economy was worsening fell to 48% from 54%.”

This is important because consumer sentiment has been on the decline since prices started rising three years ago. When consumers feel better about the economy, they’re more likely to spend money—and that consumer spending creates jobs.

What’s remarkable about this period of high prices is that consumer spending rose even when adjusted for inflation—likely thanks in part to those growing paychecks that we were talking about in the introduction. “The Commerce Department on Friday reported that consumer spending rose 0.5% in July from June. That put it up 5.3% from a year earlier—or 2.7% after adjusting for inflation,” the WSJ notes.

Additionally, “The Commerce Department on Thursday revised gross domestic product growth for the second quarter higher largely on the strength of consumer spending. Economists expect third-quarter spending will remain solid, and several revised their third-quarter GDP estimates upward on Friday.”

If consumer spending has been solid throughout a period of high inflation, imagine what workers would do with bigger paychecks in a time of steady prices and economic optimism. It’s exciting to imagine the kind of economic growth this whole country might see if middle-out economics gets to kick into high gear.

Kroger Executive Admits to Price-Gouging

“Kroger Co. hiked prices on milk and eggs more than needed to account for inflation, the company’s top pricing executive testified during a court hearing on the US government’s bid to block the grocery chain’s purchase of rival Albertsons Co,” reported Bloomberg last week.

At Common Dreams, Jake Johnson writes, “Andy Groff, Kroger's senior director for pricing, said during a court hearing on the FTC's legal challenge to the company's proposed acquisition of Albertsons—its primary competitor—that Kroger's objective is to ‘pass through our inflation to consumers.’”

“Groff's comment came in response to questioning about an internal email he sent to other Kroger executives in March,” Johnson continues. “In that note, Groff observed that ‘on milk and eggs, retail inflation has been significantly higher than cost inflation.’”

This isn’t exactly news—CEOs have been bragging on earnings calls for the last two years about raising prices way above costs in order to pump up their profit margins to record heights. In 2022, Lindsay Owens rang the alarm bell in the pages of the New York Times:

As Hostess’s C.E.O. told shareholders last quarter, “When all prices go up, it helps.” The head of research for the bank Barclay’s echoed this. “The longer inflation lasts and the more widespread it is, the more air cover it gives companies to raise prices,” he told Bloomberg. More than half of retailers admitted as much when surveyed.

Executives on their earnings calls crowed to investors about their blockbuster quarterly profits. One credited his company’s “successful pricing strategies.” Another patted his team on the back for a “marvelous job in driving price.” These executives weren’t just passing along their rising costs; they were going for more. Or as one C.F.O. put it, they were “not leaving any pricing on the table.”

But in this case, the Kroger executive’s bragging has come back into the spotlight because his company is trying to buy their competitor, Albertsons, and form a single gigantic grocery chain. If a company is willing to jack up prices to pad profits in the middle of a supply-chain crisis caused by a global pandemic, they’ll obviously be willing to slash wages and raise prices when they’ve killed competition in huge swaths of the United States.

Trickle-Down in Space

“Two astronauts, Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore, arrived at the International Space Station on June 6, expecting to stay for just over a week,” writes Clive Irving for the New York Times. “Now they won’t be heading back to Earth until February.”

Outer space might sound far afield of our usual subject matter, but Irving explains that those astronauts were delivered to the Space Station by a Boeing spacecraft, and now they’ve been stranded for months because the ship was “deemed by NASA to be too risky for the return trip because of a host of troublesome technical glitches.”

Boeing has become known for its growing inability to manufacture quality air and spacecraft—remember, an entire fleet of Boeing jets were grounded around the world after several crashes in 2019 and 2020, and just this year, Boeing planes started losing parts mid-flight. This deterioration in quality is the result of years of corporate leaders prioritizing profits above quality, slashing the meticulous safety standards that for decades were Boeing’s pride and joy. (For more information about Boeing’s decline, watch this excellent Pitchfork Economics explainer video.)

But this latest boondoggle isn’t just affecting Boeing’s already-sullied reputation—it’s affecting the future of America’s space program.

“NASA’s Artemis program, aiming to return to the moon by 2026, depends critically on the Space Launch System, a massive launch rocket developed largely by Boeing,” Irving writes.

He continues, “That was successfully tested in 2022 when NASA launched an unmanned spacecraft into a lunar orbit. But it emerged in a report this month that NASA’s Office of Inspector General has serious concerns about Boeing’s work on an upgrade of the rocket needed for a second moon landing in 2028.” Because Boeing can’t be trusted to build a functioning rocket, our national plans to return to the moon might be at risk.

Of course, this is also an indictment of the government’s trickle-down tendency to embrace public-private partnerships rather than investing deeply in its own space programs, as we did during the space race in the middle of the 20th century.

The Alliance for Innovation and Infrastructure points out that investments that the federal government made in the space program back then resulted in the creation of technology that changed the way we live today, including “medical imaging techniques, durable healthcare equipment, artificial limbs, water filtration systems, solar panels, firefighting equipment, shock absorbers, air purifiers, home insulation, weather resistant airplanes, infrared thermometers,” and cell phones. Had those technologies been developed in a public-private partnership, a handful of corporations likely would have been able to monopolize those patents for generations. Instead, we all benefit from those discoveries.

Despite what you may have heard in your Econ 101 course, not every human problem can be solved efficiently through the free market. Government is very good at directing private industries toward outcomes that are better for society—as in the Biden Administration’s investments in semiconductor manufacturing and green energy—and it’s also great at setting and working toward big goals like the space race. Boeing is creating a fantastic argument against letting the free market reach solutions on its own when safety and efficiency are at stake.

This Week in Middle-Out

News broke yesterday that the Biden Administration is preparing to block Nippon Steel’s acquisition of US Steel. “The president had previously outlined opposition to the deal in March, saying it is ‘vital for it to remain an American steel company that is domestically owned and operated,’” reports CNN.

Peter Coy interviewed Senator Amy Klobuchar about her legislation to ban algorithmic price-fixing. The practice allows online vendors (and perhaps someday soon, brick-and-mortar retailers) to use existing knowledge about individual consumer behaviors to change the prices on individual items in order to charge the absolute most that a customer is able to pay. If the algorithm knows you recently got a raise, for instance, the retailer will charge you more for a pair of pants than someone else. “It’s mind-blowing what could go wrong here unless something is done,” Klobuchar told Coy.

Andrew Duerhen at the New York Times explains what’s at stake when the Trump tax plan expires next year. For a potential Harris Administration, there’s a possibility to enact “politically palatable plans for increasing taxes on very high earners and large corporations. The goal is to raise more than enough revenue to cover the costs of extending other tax cuts,” Duerhen says.

The results of a large guaranteed income program that gave cash benefits directly to thousands of people are in, Emma Goldberg reports, and the results are not quite as overwhelming as they have been in some of the smaller guaranteed income pilots of the past. “People gained flexibility to spend on basic needs, but the cash didn’t transform their net worth or their mental or physical health,” Goldberg writes. “Some researchers and guaranteed income proponents argue that the study shows that cash transfers are only a small piece of the larger puzzle of how to improve the financial well-being of low-income people.”

Vox takes a deep dive into the ongoing quest to regulate artificial intelligence in the state of California. If Governor Newsom signs a bill that passed the state legislature into law, Vox explains, it “would offer whistleblower protections to tech workers, along with a process for people who have confidential information about risky behavior at an AI lab to take their complaint to the state Attorney General without fear of prosecution. It also requires AI companies that spend more than $100 million to train an AI model to develop safety plans.”

This week, Kamala Harris announced a plan to jumpstart some 25 million new small businesses in her hypothetical first term. Axios explains that her plan includes “a tenfold increase in the tax deduction for starting a small business — from $5,000 to $50,000,” and a new rule saying “new businesses will be allowed to wait to claim that deduction once they turn a profit.” She would also direct 1/3rd of all federal contract spending to go toward small businesses.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Nick and Goldy engage in a conversation this week about Vice President Kamala Harris’s economic vision, and about the economic platform laid out at this year’s Democratic National Convention. They come to two big conclusions: First: Harris is all-in on middle-out economics. And second, and perhaps most surprisingly: The whole Democratic Party seems to be in lock-step behind her.

Closing Thoughts

We’ve been saying for the better part of a year that the Federal Reserve needs to start cutting interest rates in order to bring down the cost of mortgages, loans, and credit card debt for working Americans. It has been clear for some time that the Fed’s campaign of lowering interest rates were not having an impact on inflation—in fact, those rising prices were due to supply chain disruptions during the pandemic and a wave of greedflation that erupted when corporations took advantage of inflation panic to jack up prices and rake in record profits.

Finally, it seems that the Fed has come around. “The Federal Reserve is ready to cut interest rates, confident that inflation is easing to normal levels and wary of any more slowing in the job market,” writes the Washington Post’s Rachel Siegel. She quotes a speech from Fed Chair Jerome Powell from last month that signaled impending rate cuts: “The time has come for policy to adjust. The direction of travel is clear.”

“We will do everything we can to support a strong labor market as we make further progress toward price stability,” Powell said in his speech. “With an appropriate dialing back of policy restraint, there is good reason to think that the economy will get back to 2 percent inflation while maintaining a strong labor market.”

Many are wondering if the Fed has waited too long to enact these rate cuts. This week’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey saw 237,000 fewer job openings in August than in July, and there are now only 1.1 open positions for every worker seeking work, bringing us back to pre-pandemic levels of employment.

High interest rates aren’t just making the job market tougher—they’re also making housing much more expensive. The Roosevelt Institute reports that in addition to helping lower the cost of housing, lowering interest rates will also benefit “other industries that face high upfront costs, such as renewable energy development, [which] could also invest more in major projects if interest rates went down. And the Fed’s decisions don’t just impact the United States—high interest rates have also exacerbated the debt burden on emerging economies.”

“The question going forward is how readily the Fed’s earlier damage can be reversed,” Robert Kuttner writes at The American Prospect. “Most economists think the economy is still on track for decent growth and low inflation next year. But we could have done even better had the Fed not been so obsessed with inflation, especially since most price increases since pandemic supply chains eased are structural rather than macroeconomic, reflecting excess corporate market power to raise consumer costs.”

We’ll learn the Fed’s ultimate decision when the Fed meets next, on September 17th and 18th. I’ll undoubtedly have much more to say about the matter then.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach