Friends,

On Friday afternoon, grocery chain Kroger announced its intention to merge with Albertsons, another national grocery chain. The merger would combine Albertsons brands nationwide like Safeway, Shaw’s, Osco, and Star Market with Kroger brands like QFC, Fred Meyer, and King Soopers. “If approved by regulators, the nearly $25 billion deal would be one of the biggest in US retail history,” writes CNN’s Nathaniel Meyersohn.

It’s really stunning for two of the largest grocery chains in the nation to announce an all-cash merger in a year when corporate greed has forced grocery prices up by 13%. The press release announcing the merger throws some lip service toward a promise that the merged grocery chain will dedicate a billion dollars to lowering prices for consumers. But that seems hard to believe, given that Kroger recently announced a $1 billion stock buyback program which enriched the shareholder class at the same time it closed stores rather than offer a $4 pandemic-era “hero pay” to its employees.

Because the Kroger and Albertsons chains overlap in many parts of the country including California, western Washington, and Virginia, stores in those areas will be closed and workers will be laid off if this merger goes through—and it goes without saying that stores with a strong union presence will likely be targeted for closure over stores with less union power.

So consumers and workers are likely to lose out on this deal. Who will win? A private equity firm called Cerberus Capital Management—unbelievably named after the mythological three-headed dog who guards the gates of Hades—which orchestrated the merger and stands to take home $7 billion if it goes through. And Albertsons’ executive team would pocket a total payout of nearly $100 million.

But the handouts to the investor class don’t stop there. Eileen Appelbaum notes that “as part of the transaction, Albertsons Companies will pay a special cash dividend of up to $4 billion to its shareholders of record on October 24, 2022. A dividend of this size could bankrupt the debt-ridden supermarket chain.”

This last bit is particularly devious: Albertsons is basically forking billions over to the investor class in an effort to financially weaken itself so Kroger “can argue that Albertsons will face bankruptcy if the merger is not approved.”

Leaders like Senator Elizabeth Warren have already sworn to stop this merger. Representative Katie Porter announced yesterday on Twitter:

Many pundits have predicted that the merger won’t go through—though it should be noted that most of those analysts haven’t acknowledged the $4 billion Albertsons buyback suicide plan that would imperil the company and make a merger a necessity for its survival. And multi-billion dollar mergers don’t stop themselves. Our leaders will have to make some important decisions to grind this thing to a halt before workers and consumers have to pay the price.

Once you dig past the corporate cheerleading-speak, there’s an air of desperation to this merger announcement, a clear acknowledgement that it’s for nobody’s benefit but the executive shareholder class. It’s too soon for polling results to come in, but I’d place a good-sized bet that most people know this deal won’t work out in their favor—past experience (as well as a basic understanding of how economics really works) demonstrates that less competition is bad for consumers.

It’s up to our leaders to stand up and do everything in their power to unspool this merger—all of it, from the buybacks to the profiteering to the axing of good union jobs. We say often in this newsletter that doing popular things is popular, and the corollary to this rule is that fighting wildly unpopular decisions is wildly popular. This is a significant moment in the battle against extractive, vulture capitalism, and middle-out politicians can use it as an example of how to invest in the many over the wealthy few.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

A growing consensus against raising rates

Last week, we warned that the Federal Reserve’s interest-rate increases didn’t seem to be bringing inflation down. An excellent Guardian piece by Tom Perkins has collected other dissenting voices into a chorus: “Experts say raising rates ‘isn’t working’ and that the real culprits are corporate pricing, energy costs and supply chain [disruptions]”—and the fact that two of the largest grocery chains in America are trying to rake in billions of dollars through a merger only further demonstrates that this inflationary crisis bears no relation to the crisis of the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Perkins investigates the supply chain issues caused by the pandemic and rising energy costs brought on by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Policies in the United States and the European Union are working toward resolving at least some of the pain inspired by those two factors. But the bigger problem is greedflation—corporations raising prices not because they are necessary but simply because they can get away with it.

“An April Guardian analysis of 100 top corporations SEC filings found 80 had increased net profits between 2019 and the corresponding quarter in 2021 or 2022, while inflation had eaten into most workers’ wage gains,” writes Perkins. And several corporations, including Colgate, have publicly refused to back down from their slate of price increases.

You’d expect financial firms to suffer in times of high inflation, since people have less money to invest, but big banks and investment firms are still thriving. “Goldman Sachs, Johnson & Johnson and Lockheed Martin reported quarterly profits that beat analysts’ expectations on Tuesday, a day after Bank of America, Charles Schwab and other bellwether firms reported surprisingly robust results,” reports Isabella Simonetti for the New York Times.

Also for the Times, Emily Flitter digs into the Bank of America report for a little more information. “The second-largest bank in the country earned $7.1 billion in profit in the third quarter, an 8 percent drop from a year earlier but more than analysts were expecting. Consumer deposits grew 1 percent, and credit card spending rose 13 percent,” she writes.

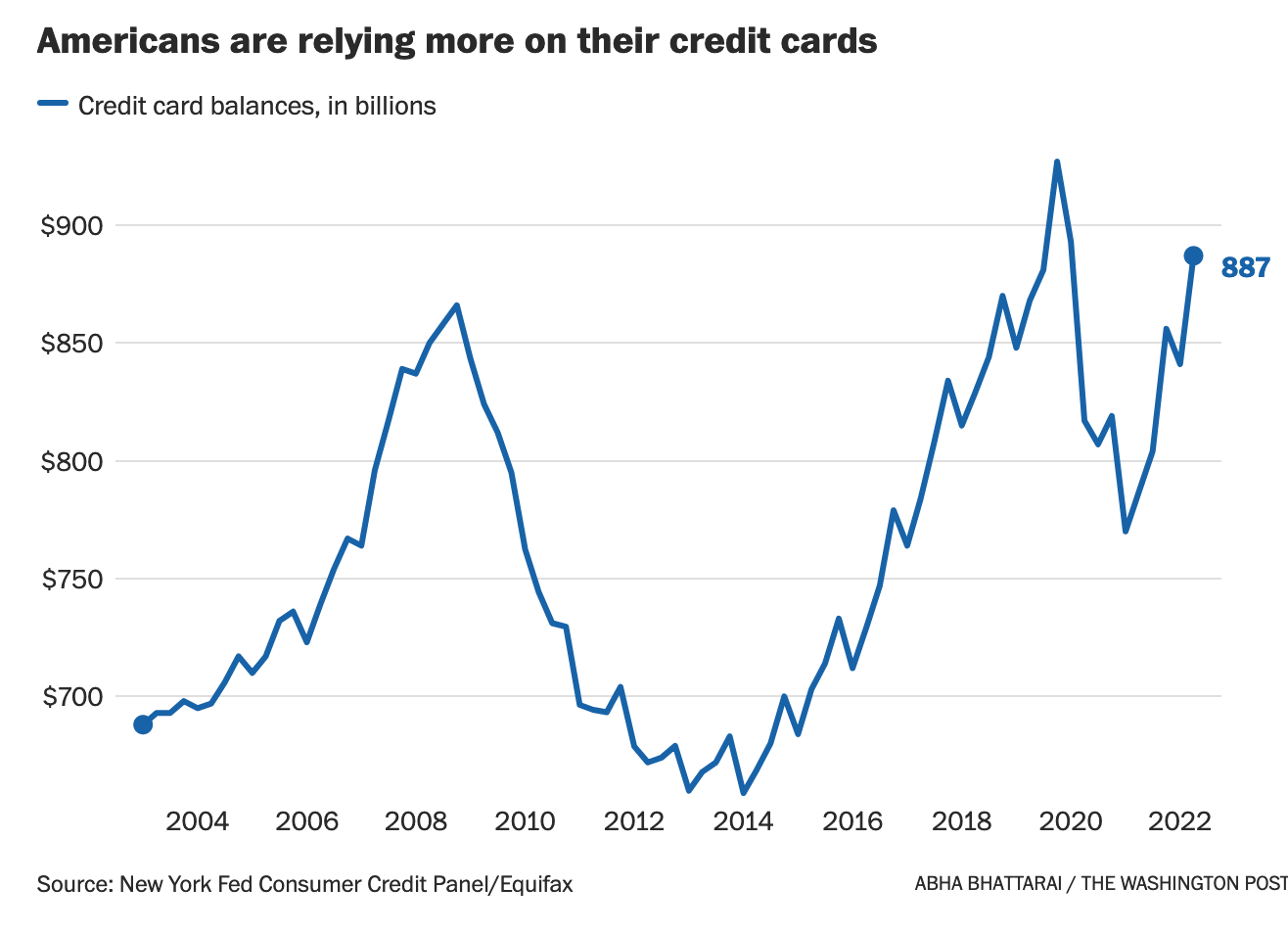

That 13-percent increase in credit-card spending at Bank of America exactly mirrors the 13-percent increase in America’s total credit card debt over last year. According to Abha Bhattarai at the Washington Post, our total debt has ballooned to $887 billion dollars.

As the debt has increased, so have credit card interest rates: “Average credit card rates, at 18.7 percent, are at their highest level in 30 years and will probably continue rising,” Bhattarai writes. Americans are spending more just to stay afloat due to rising prices, and the price for that spending, when the bills come due, will be higher than many people will be able to afford.

The rent (algorithm) is too damn high

You should definitely pay attention to this ProPublica story by Heather Vogell explaining how many of the rent increases that have happened in America recently are the result of one algorithm. After a merger between two large property management software firms, a company called RealPage created an algorithm in a program called YieldStar that takes private data and local rental rates into account when formulating new rents and rent increases. Now that 70 percent of the apartments in a single Seattle neighborhood are owned by management companies that use this software, the rent increases seem to be magnifying.

There are questions of violation of consumer privacy and corporate collusion here: YieldStar incorporates all of its clients’ data into the algorithm—even at supposedly competing apartment buildings across the street from each other that are owned by different landlords. With that in mind, the algorithm starts to potentially bump against the idea of price-fixing.

“RealPage discourages bargaining with renters and has even recommended that landlords in some cases accept a lower occupancy rate in order to raise rents and make more money,” Vogell writes. “One of the algorithm’s developers told ProPublica that leasing agents had ‘too much empathy’ compared to computer generated pricing.”

Firms using YieldStar take in almost 5 percent more rent than at comparable property management firms in the same market. And pushing up those rents does push some people out—one account in the story found that turnover increased by 15% in YieldStar properties, but revenue increased by 7.4% in the same year. While human landlords may generally prize stable, responsible tenants, YieldStar’s algorithm plays a numbers game, maximizing short-term profits over occupancy or duration of a tenant’s stay in a property.

“The net effect of driving revenue and pushing people out was $10 million in income,” one property manager said, adding, “I think that shows keeping the heads in the beds above all else is not always the best strategy.”

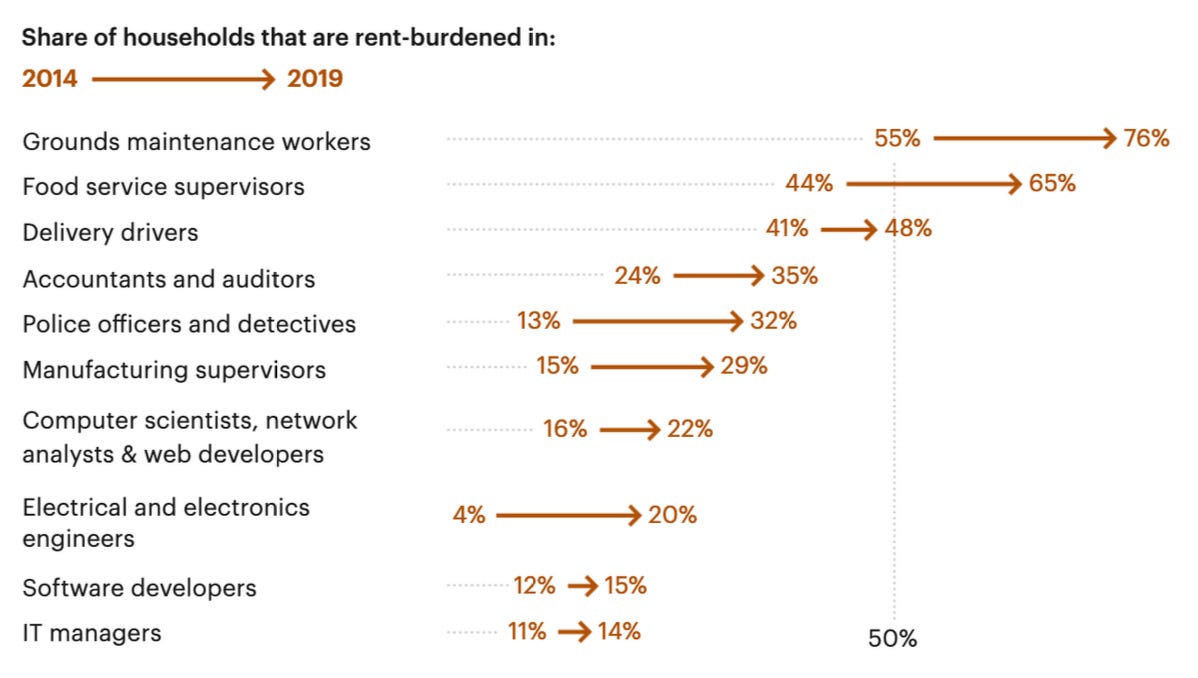

The young tech employees and other professionals living in big downtown properties can afford to pay the escalating rents. But middle- and working-class Americans are being priced out of buildings in cities around the country. I found this chart in the ProPublica story to be particularly fascinating: In Seattle, workers in service industry jobs became rent-burdened at an alarming rate from 2014 to 2019.

Again and again, we see that prioritizing short-term profits over long-term stability might result in some truly spectacular quarterly earnings statements for a while. But the flip side of those big profits is an ever-growing pool of human misery—evictions, people being priced out of the market, an increase in unhoused populations—that eventually swells big enough to flood the entire system. And when rents increase to consume two-thirds of your salary, you’re not going to have money to spend in your community, stifling economic growth to feed big landlords.

Conditions like this are why, Conor Doughterty reports for the New York Times, renter unions and pro-renter activist organizations have “brought organizing muscle and policies like rent control to cities far beyond the high-cost coasts.” His piece profiling several renter activist organizations in Kansas City is required reading.

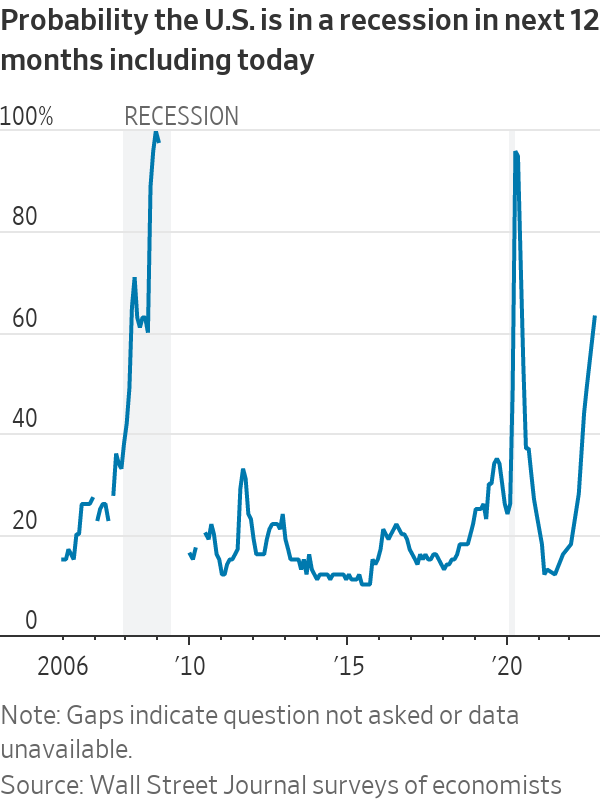

Economists predict a recession within the next 12 months

The Wall Street Journal’s survey of economists delivers some bad news: “On average, economists put the probability of a recession in the next 12 months at 63%, up from 49% in July’s survey. It is the first time the survey pegged the probability above 50% since July 2020, in the wake of the last short but sharp recession,” Harriet Torry and Anthony DeBarros write.

For what it’s worth, the GDP contraction those economists predict is on the small side—they expect GDP to shrink by .2 percent in the first quarter of next year and .1 percent in the second. But this report should come preloaded with a number of caveats: First of all, economists’ predictions are frequently wrong.

And second of all—and even more importantly—the GDP is not the economy. It doesn’t reflect the lives of ordinary Americans. What economists refer to as a “minor contraction” of GDP will likely result in layoffs and skyrocketing unemployment for many thousands—even millions—of Americans. One economist’s “small recession” is a life-changing disaster for American households.

This week in middle-out economics

Here are the middle-out policies that made headlines this week:

President Biden invested $2.8 billion into grants to increase U.S. production of electric vehicle batteries in 12 states including North Dakota and North Carolina. These grants will fund the creation of battery production factories and ore mining facilities, reshoring jobs from China and working toward the Biden Administration’s goal of ensuring that half of all vehicles sold in America in 2030 are electric.

This election season, New Mexico voters could make universal pre-K and childcare a right, reports Rachel M. Cohen at Vox. “The measure would authorize lawmakers to draw new money from a state sovereign wealth fund to provide a dedicated funding stream for universal preschool and child care, and bolstering home-visiting programs for new parents,” she writes. The policy is polling well across party lines, with even Republicans coming in 56% in favor. Turns out, creating a program that economically benefits everyone is pretty popular.

Despite fears from experts that child abuse would rise during the early days of the pandemic, new analysis finds that child abuse actually declined in 2020, “in large part due to the substantial government investment in keeping families financially afloat during the economic shutdown,” Caleb Brennan reports at The American Prospect. Economically stable parents are less likely to criminally neglect or abuse their children.

The Roosevelt Institute just released five major lessons from its recent forum on reinventing industrial policy through a progressive lens, including the importance of keeping climate change in mind with every decision, creating new frameworks for our international trade policies, and investing directly into communities that have traditionally lost out from past industrial booms.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Join us at 10:30 am PT tomorrow for Civic Action Live, when we’ll talk about the growing chorus against the Federal Reserve’s push to raise rates, the recently announced merger between grocery giants Albertsons and Kroger, and why it’s bad news that fewer employers are investing in their workers.

On the Pitchfork Economics podcast, Nick and Goldy talk with author, journalist, and publisher Michael Tomasky about his new book, The Middle Out: The Rise of Progressive Economics and a Return to Shared Prosperity. If, like many people, you just started hearing about middle-out economics this year, you might find this podcast about the deep roots of its origins to be particularly illuminating.

And for Insider, Paul explored the expanding inequality of the housing market, in which homeowners increasingly use their houses as a significant share of their retirement income and in so doing price out an ever-growing share of the potential home-buying market.

Closing Thoughts

Feeling adrift from a Republican Party overwhelmed by Trumpism, former Mitt Romney advisor Oren Cass has been working to forge a new economic vision for American conservatives at his think tank American Compass. Cass’s latest column at the Financial Times highlights an economic issue that Americans on both sides of the aisle should agree is a vital one.

“Business leaders who complain constantly of ‘talent shortages’ or ‘skills gaps’ may, in fact, have only themselves to blame,” Cass writes. He asks, “Why do employers believe they should have access to whatever labor they need at whatever wages they choose?” He cites as examples, “the software executive who expects an unlimited supply of eager coders, or the plant manager who believes well-trained technicians will line up at his door.”

Rather than asking why nobody wants to work anymore, Cass argues, it might be time for employers to take a long look in the mirror and ask why they don’t want to pay workers for their expertise, and why they’re unwilling to invest in the training and development of employees to meet new demands.

To illustrate what he means, Cass links to The American Opportunity Index, a survey of America’s 250 biggest employers across nine different metrics in order to determine “the opportunity a firm affords workers or helps create beyond it, as indicated by the access to work it provides, the upward mobility workers experience, and the pay it offers.”

Of those 250 firms, Cass notes, “Those in the top quintile for providing access are hiring four times as many candidates without prior experience as those in the bottom quintile. Those in the top quintile for mobility are two-and-a-half times more likely to fill openings by promoting from within and twice as likely to have senior management following that route.”

“In short,” Cass concludes, “most companies could be casting a wider net in hiring, offering better pay, or investing more effectively in workers’ success and progression.” It used to be that employers would develop and educate their workers to rise in the ranks and to meet new challenges over the course of their careers. But the past 40 years of globalization and widespread low wages has inspired employers to consider workers to be disposable single-use tools: they hire workers to perform very specific tasks, and then they toss them out when those needs have been met.

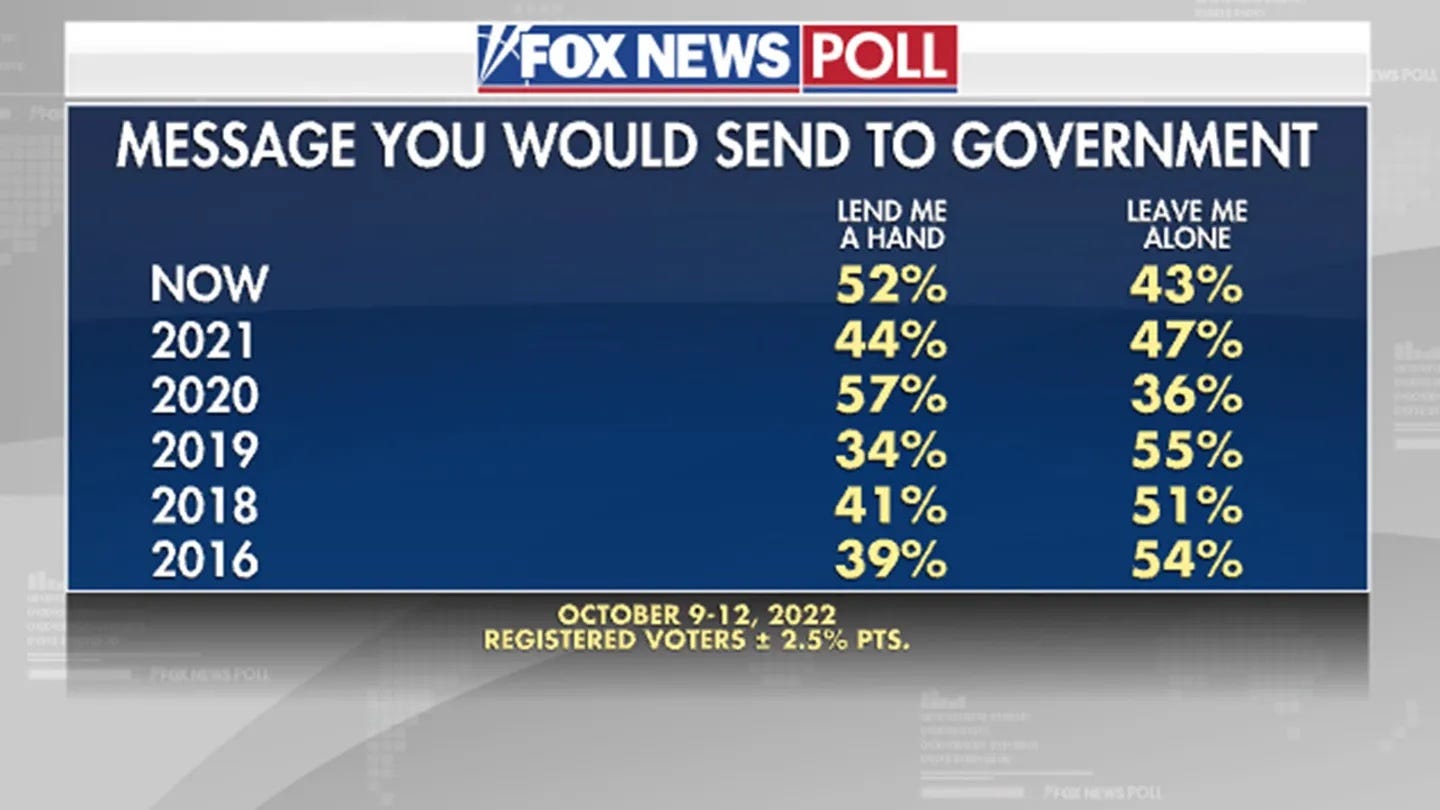

Cass and I would very likely come to different conclusions about how to resolve this problem, but it’s refreshing that we both recognize it as a problem—that’s the starting point for meaningful political discussion, regardless of party. And given that even Fox News polls now find that the majority of Americans, for the second time since the pandemic began, want the government to “lend me a hand,” as opposed to “leave me alone,” it seems that the public desire for problem-solving is on the rise.

Be kind. Be brave. Get vaccinated—and don’t forget your booster.

Zach