Growing the Economy From the Bottom Up & Middle Out

The Pitch: Economic Update for April 10th, 2025

Friends,

One of the foundational understandings of middle-out economics is that income inequality has exploded over the last forty-plus years, and that inequality is bad for the economy and the democracy. That’s because working Americans create economic growth with their paychecks – or to paraphrase Nick Hanauer: a thriving middle class is the cause of economic growth, not the other way around. When you impoverish working people and shrink the middle class, you stunt your economy, harm your democracy, and create havoc across society.

Only recently have we put a price tag on that inequality, thanks to a new report from the nonpartisan RAND Corporation. Since 1975, nearly $80 trillion has been sucked out of the paychecks of the bottom 90% of working Americans and deposited into the coffers of the wealthiest 1%. That’s why modern American families have to work twice as hard in order to earn half as much wealth as similar families did 50 years ago. The numbers here are staggering and if you wanted to explain what’s wrong our country in one chart this one would do it:

But not all is lost. Our friends at the Economic Policy Institute have put together a new report that proves that we can make different choices that help solve this problem. With the right policy solutions, we can turn the tide of income inequality. How do we know that it’s possible? Because over the last five years, we made a small dent in income inequality by growing the paychecks of the Americans at the bottom half of the wage scale.

“Between 2019 and 2024, there has been a notable reversal of long-term trends in wage growth. Low-wage workers experienced historically fast real wage growth (adjusted for inflation) and the strongest wage growth compared with workers at all other parts in the wage distribution,” write Elise Gould, Katherine deCourcy, Joe Fast, and Ben Zipperer at EPI.

“The hourly wage for the lowest-paid workers at the bottom 10% grew a tremendous 15.3% over this period,” they write. “The wage growth at the lower end of the wage distribution was exceptional, significantly faster than their average growth in the prior 40 years and faster than higher-wage workers over the same five-year period.”

And those wage gains helped share the wealth among groups that have traditionally been left behind in the 21st century American economy: “Black and Hispanic workers, young workers, and workers with lower levels of educational attainment experienced relatively fast wage growth over the last five years,” the authors conclude.

The below chart from the report is breathtaking: The poorest decile of American workers is on the left and the richest are on the right. The dark blue bars represent the annualized wage growth of workers in each decile from 1979 to 2019. You can see that wage growth was fairly small for all groups, and the less you earned the lower your wages grew.

The light blue bars, though, represent the wage growth each group saw between 2019 and 2024. You can see that the lowest decile saw nearly 3% growth in that period, with the 2nd decile coming in at a strong 2.2%. (Note that every income group saw their wages rise significantly over the last five years, which puts the lie to the trickle-down argument that every economy is made up of winners and losers in a zero-sum game.)

The authors prove that while state and local minimum-wage increases did increase the paychecks of low-wage workers, they weren’t the only reason for that remarkable rise in wages. What’s the reason for this striking shift? “Policymakers responded to the pandemic recession with actions that made a real difference in people’s lives: Wages grew for those who needed it most,” the authors write.

There’s no mystery about what caused these gains for the lowest-wage workers: “An expansion of child tax credits, unemployment insurance benefits, food assistance, and direct payments all contributed to the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and made the labor market the strongest it has been in a generation,” the authors write, concluding that “Thoughtful policymaking going forward can help ensure that lower-wage workers continue to see improvements in their standard of living.”

Of course, these gains were a drop in the bucket compared to the 40 years of consistent losses that working Americans saw in their paychecks. And there’s another gap between wage growth and the accumulation of wealth—wages need to grow consistently over time for workers to gain back the wealth that previous generations have to lost. This is not a mission-accomplished moment for the American economy. But it does prove that income inequality isn’t some universal truth like gravity.

The authors recommend that to keep this shift toward a more equal economy going, leaders should raise the minimum wage federally and in states that keep their wages artificially low. And they suggest that leaders enact other policy solutions, including ending the Trump Administration’s policies of slashing government jobs, cutting assistance programs that invest in working Americans, and halting the waves of deportations.

While the economic status quo will no doubt try to poke holes in this report and complicate its conclusions, it really is just this simple: We made a significant difference in the lives of Americans with smart policies that invested in workers, and we saw real results in the existential fight against inequality. We know what worked. We can do it again.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Inflation Cools…for Now

“Inflation cooled unexpectedly sharply in March,” Colby Smith reports today for the New York Times. “The Consumer Price Index climbed 2.4 percent last month from a year earlier, a far slower pace than February’s 2.8 percent increase and the lowest annual rate since September,” Smith continues. “Over the course of the month, prices fell 0.1 percent.”

The core inflation number, “which strips out volatile food and energy items, slipped to 2.8 percent in March, following a 0.1 percent monthly increase,” Smith writes. “Overall, that is the slowest annual pace for “core” inflation since 2021.”

Under virtually any other conditions, this would be good news—a surprising positive sign that price increases are slowing for American families. But Smith reports that “economists warn that the positive news is unlikely to last with costly tariffs now in effect against China and other trading partners.”

“We don’t see tariffs as a one-time price shock. We see them as having significant second round effects,” said James Egelhof, chief U.S. economist at BNP Paribas. “We expect that tariffs will first impact goods prices and then ultimately move through wages as the labor market remains fairly tight. That feeds back and affects other goods prices and services as well and creates a cycle in inflation."

We’ll of course have more to say about the chaos surrounding tariffs, and their potentially huge impact on prices, a little later on in this newsletter.

Consumer and Small Business Sentiment Continues to Plunge

It seems as though every week, there are new negative consumer sentiment numbers to report. This week is no different, as Axios reports that “Consumer confidence dropped precipitously on Monday, as Americans absorbed news on stock market plunges and sky-high tariffs.”

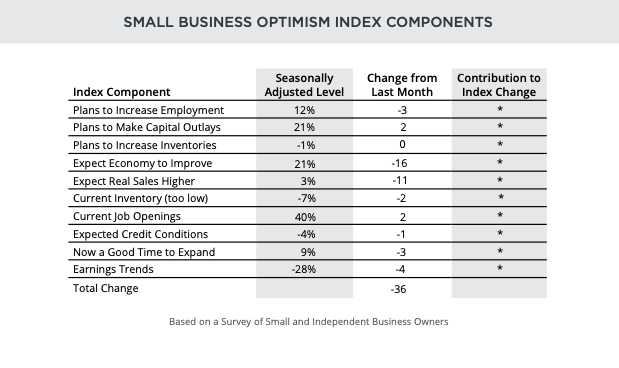

That glum sentiment is matched by new numbers in the March report (PDF) from the National Federation of Independent Businesses. The NFIB’s “optimism index” shows that small business owners are roundly expecting economic conditions to worsen. From cutting plans to hire workers to scuttling plans to add inventory and expand businesses, the whole report is bad, but the numbers on “expect economy to improve” and “expect real sales higher” particularly dipped, with double-digit decreases over February:

It’s easy to feel a little jaded after seeing week after week of plunging self-reported sentiment numbers while big economic indicators like unemployment and inflation numbers keep coming in either at a steady clip or slightly down. What could all that sentiment amount to, after all, if American workers keep the economy humming along?

This week, those plunging numbers have broken through into the first solid non-sentiment based economic indicator in the form of the February consumer borrowing report. “US consumer borrowing unexpectedly declined in February for the first time in three months,” as well as “a decrease in motor vehicle and other non-revolving loans,” reports Bloomberg.

“Outstanding credit-card and other revolving debt edged up $128 million. Non-revolving debt, such as loans for vehicle purchases and school tuition, declined $938 million, the first drop in nearly a year,” they continue.

This looks to me like the economic uncertainty behind those bad consumer sentiment numbers escaping containment and entering the real world. If nobody is sure what shape the economy will be in next year, one of the first things most people would do is cut back on big expenses that would incur monthly payments for the next few months and years.

Kicking the Tariff Can Down the Road

As I write this, it looks as though President Trump has delayed many of the sweeping tariffs that he introduced one week ago, claiming that they will eventually be enacted in 90 days. Currently, there are still three-digit tariffs on Chinese imports and ten-percent tariffs on most other nations—though nobody seems to know for sure which tariffs have been levied on which nation and which tariffs have been lifted.

To be clear, this isn’t a “pause” on tariffs, regardless of what newspapers have been reporting. The ten percent tariffs that Trump left in effect are still higher than any tariff levied by the United States in the last nine or so decades, and they will cost American families anywhere between two and four thousand dollars this year—and that calculation doesn’t even take the supposed 145% tariffs on Chinese goods into account.

While—again, as I write this—the stock market responded to Trump’s tariff reprieve by soaring into the positive after days of declines, and then plummeting again this morning, it seems highly unlikely that any Wall Street response to this weeklong misadventure, in which the highest tariffs were actually in place for less than 24 hours, will help those declining economic confidence levels I was talking about above.

Remember, the stock market is not the economy. It’s a mood ring that reflects the fickle emotions of the super-rich executives on Wall Street. But to business owners on Main Street who are wrestling with high costs and unpredictable consumer patterns, this continual two-step with tariffs being levied and repealed seemingly at random makes it almost impossible to plan for the future. And for Americans who are weighed down with high housing costs, big grocery bills, and fluctuating energy prices, any necessary big purchases seem more like unacceptable risks.

For The Atlantic, Annie Lowrey offers a look at the economic future for most Americans if Trump’s ongoing program of tariffs continues. She does this by visiting towns on the Canadian border that are already feeling the impacts of tariffs and Trump’s aggressive economic moves:

“Residents of border towns see their shopping malls and greasy spoons half empty. They read stories in the local paper about rising construction costs and Canadians detained at border crossings,” Lowrey writes.

“They notice the lack of hiring signs. They hear about the trade war on the evening news. As a result, many are reducing their own spending in expectation of a downturn: putting off home repairs, delaying the purchase of a new car, canceling vacations, eating in instead of ordering out.” She continues:

“It is definitely having a rippling effect, and it’s been immediate,” says Michael Cashman, the supervisor of the town of Plattsburgh, New York, 20 minutes south of the border. “These may seem like small trade restrictions in Washington. But they’re devastating for our region.” He told me he was “deeply concerned” about sales-tax revenue dropping. Plattsburgh is preparing to pull back on public spending “until there is more clarity in the forecast.” Of course, the town cutting its budget would worsen the downturn.

“What is happening in Plattsburgh and Sault Ste. Marie is happening in rural Nebraska, Kentucky’s bourbon country, and Las Vegas too—in every community that relies on foreign tourists, foreign imports, foreign exports, and cross-border traffic,” Lowrey concludes. In my own state of Washington, towns that border on Canada including Blaine and Bellingham are seeing their own impacts from tariffs and trade uncertainty.

One of the qualities that makes it hard for Democratic leaders to rhetorically grab hold of Donald Trump is that he doesn’t always adhere strictly to the same trickle-down script that Republican leaders have followed for more than forty years. But one of Trump’s most foundational core beliefs is also a core trickle-down concept: In every deal, he believes, there are winners and there are losers.

Middle-out economics argues otherwise. While competition is essential to inspire innovation and to keep wages high and prices low in a capitalist economy, true economic value is created through cooperation, not competition. Good trade policies are positive-sum, not zero-sum.

It’s impossible for the United States to grow coffee at scale, for instance. So we buy coffee from other nations. We roast those beans and package them, and our restaurant chains bring their coffee to nations around the world. Here at home, those imported coffee beans support a $343 billion industry, with the National Coffee Association estimating that “Every $1 in coffee imported to the United States ends up creating an estimated $43 in value here at home.”

Only an incredibly short-sighted person would argue that America loses out on the sale of coffee beans from Brazil to America. By closing our channels of trade, the Trump Administration is trying to pull us back to a trickle-down past where a wealthy few profit while everyone else struggles to make ends meet.

This Week in Trickle-Down

“President Trump wants to use a 19th-century fuel to drive 21st-century technology,” reports Jon Keegan at Sherwood. “Trump is expected to sign an executive order today boosting the declining coal industry, positioning the fossil fuel as a cheap and reliable way to meet the staggering power demands of Big Tech’s AI dreams.”

“Trump’s Justice Department has indicated they will no longer pursue any investigations of crypto fraud,” reports Miles Klee at Rolling Stone. That’s according to a new memo from U.S. Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche, who represented Trump in the 2024 trial in which he was convicted on 34 felony counts of falsifying business records.”

The Center for American Progress has compiled an interactive map allowing you to see how many cuts the Department of Government Efficiency has made that will directly affect your state and Congressional district.

This Week in Middle-Out

Nine House Democrats have formed a “Monopoly Busters Caucus,” according to Axios reporter Andrew Solender. “Representatives Pramila Jayapal, Chris Deluzio, Pat Ryan, and Angie Craig say they founded their caucus “to fight corporate greed and promote a pro-worker, pro-consumer, and pro-small business economic agenda.”

“EPI’s analysis shows that raising the federal minimum wage to $17 by 2030 would impact 22,247,000 workers across the country, or 15% of the U.S. wage-earning workforce,” writes Ben Zipperer. “The increases would provide an additional $70 billion annually in wages for the country’s lowest-paid workers, with the average affected worker who works year-round receiving an extra $3,200 per year.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

This week’s podcast episode offers listeners a chance to listen in on a middle-out economics conference that took place last week in Washington DC. It features a live conversation with three Democratic Representatives—Ro Khanna, Delia Ramirez, and Jim Himes—about how the Democratic Party can win elections by embracing middle-out economics.

Closing Thoughts

Last Sunday, Commerce Secretary Harold Lutnick on Meet the Press explained why he thought Trump’s tariff agenda was a good thing for the American economy: "The army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little screws to make iPhones -- that kind of thing is going to come to America," Lutnick announced.

Many on the right praised Lutnick’s comments, suggesting that good factory jobs would return to America thanks to high tariffs. That, in turn, inspired a round of manufacturing nostalgia in the political discourse, reminiscing about a time when skilled workers “actually made things” in America, and they were rewarded for that work with good pay, steady employment, and a good pension on which they could retire.

Make no mistake: The nearly 10% of working Americans who work in manufacturing today are doing important work. And there will always be a role for manufacturing in the American economy. But Lutnick is pulling a clever trickle-down con with his pro-manufacturing argument, here: He’s trusting Americans to believe that factory jobs are by their nature good-paying jobs with excellent benefits. And that’s just not the case.

And Lutnick is also ignoring the fact that conditions in factories manufacturing iPhones in China have been so bad that there was a spate of suicides throughout the 2010s, along with accusations that contractor Foxconn was running the factories like a “labor camp.”

For MSNBC, Jessica Calarco debunks some of this latest wave of manufacturing nostalgia. “Those who credit manufacturing jobs for a glorious past America mistake correlation for causation. They think their parents and grandparents had the “good life” because of jobs in manufacturing,” Calarco writes.

“In reality, their parents and grandparents had that life because of unions, pensions, high marginal tax rates, and strong social policies,” she explains, “with a little post-war exceptionalism and a lot of racism and sexism thrown in.”

Because manufacturing peaked in America at a time when the middle-class was at the peak of its economic powers, the lifestyle of “getting married, living in a ‘nice’ house in a ‘nice’ neighborhood, raising kids on one breadwinner’s income, taking slideshow-worthy summer vacations, and retiring comfortably at age 65” is associated with manufacturing.

“Today, many Americans perceive that lifestyle as harder to access than it used to be, and they often assume that they can’t have it because of declines in domestic manufacturing,” Calarco explains.

But for one thing, access to that lifestyle was highly restricted along race and gender lines. “From the 1950s through the 1970s, for example, Black men and white men in the U.S. were employed in manufacturing at roughly similar rates,” Calarco writes. “Yet, the average white man working the industry was paid substantially more than his Black counterpart — a difference of more than $10,000 a year in today’s dollars.”

“Meanwhile, the women who had stepped in to staff the factories during World War II were pushed out of manufacturing jobs and often out of the workforce entirely,” she continues.

And the only reason white men were compensated well was because they worked at a time when “roughly one in three U.S. workers were union members, compared to only about one in ten today. Unions helped increase manufacturing wages and reduce wage gaps between front-line workers, managers, and CEOs,” Calarco writes.

It also helps that the tax rates on those CEOs was high: “At the federal level, the highest marginal tax rate increased rapidly after World War II, peaked at 92% in 1953, and remained above 70% until the early 1980s, after which it fell dramatically to just 37% today,” she explains.

So we have to be clear that the factory jobs on their own were not the cure to income inequality—unions fought for higher wages and worker protections, lawmakers passed regulations that kept bad actors in line, and a sane tax structure raised revenue that invested deeply in infrastructure and community benefits.

Part of the impetus behind the Fight for $15 was the idea that, as Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer has pointed out, Starbucks baristas have just as much to contribute to the economy as automobile line workers. But we’re continually told that service jobs are less valuable than factory work. That is patently untrue: Starbucks pulled in just shy of $25 billion in gross profit last year, a total that is much higher than Ford’s $656 million profit in 1972, which only works out to $4 billion in today’s dollars.

As Nick likes to say, you’re not paid what you’re worth—you’re paid what you can negotiate:

It all boils down to this: In postwar America, factory workers had the leverage (thanks to unions) and the institutional support (thanks to a strong regulatory structure) to demand high salaries and good benefits. With that kind of support, today’s workers could do the same—whether they work in factories or in retail sales.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach