Friends,

During election years, we hear a lot from pundits about the importance of centrism. Self-described centrists love to position their policies smack in the center of some idealized zone midway between the right and the left. Editorial writers will often decry both Republican and Democratic politicians while solemnly intoning that the truth always lies somewhere in the middle.

For the New Republic, Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer wrote a new piece that challenges the conventional wisdom of what centrism is and puts forth a new definition.

“Self-described centrists often pride themselves on reaching across the aisle to negotiate bipartisan compromise. But ideological centrism can’t be as simple as just splitting the difference,” Nick writes. He uses the minimum wage as an example: “Splitting the difference between $15 and $0—that’s the essence of the Project 2025 proposal, which would allow states to opt out of enforcing a minimum wage at all—would set the federal minimum wage at just 25 cents more than the current $7.25-an-hour rate that has been relentlessly eroded away by inflation for the 15 years that have passed since the last increase in the federal minimum wage.”

“That’s not centrism,” Nick argues. “That’s defending the status quo, a quintessentially conservative instinct that has long been associated with the political right.”

Because America’s wealth inequality has grown unchecked for the better part of 40 years, defending the status quo amounts to balancing the wealth of the richest 1 percent of the population against the needs of everyone else. This classic centrist position is by definition a trickle-down worldview.

Since practically the first day of her presidential campaign this year, political columnists have urged Harris to “pivot to the center, right now.” They have called on her to take on more conservative positions that will upset the Democratic faithful, as though their anger is somehow the key to winning an election. The conservative positions they insist she adopt are almost always economic policies that benefit the wealthy while offering little-to-no benefits for 99 percent of the population.

By contrast, Nick explains that “a majoritarian centrism focuses its policies more on outcomes than on ideology.” He applies a two-point test to determine whether a policy is truly majoritarian. First, “Is the policy broadly beneficial?” And second, “Is the policy broadly popular?” Nick then applies that two-part test to Vice President Kamala Harris’s proposed policy platform.

“Among Harris’s signature proposals is to cut taxes on more than 100 million working- and middle-class families through restoring and enhancing the Child Tax Credit, or CTC, and the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, with the costs paid for by increasing the tax on stock buybacks, enacting a billionaire’s tax, and raising the capital gains tax rate for those earning more than a million dollars a year,” Nick writes. “All of these proposals score as both broadly popular and (unless you’re a recalcitrant trickle-downer) broadly beneficial, so they are majoritarian centrist to their core.”

Nick goes through each of the main pillars of Harris’s proposals, including housing affordability measures, small business assistance, and taking on Big Pharma. Each of those proposals would support the vast majority of Americans by investing deeply in the Great American Middle Class, making them centrist through and through.

“Of course, the obvious question, the one that is always hurled at Democrats who propose good things, is “How are you going to pay for it?” And the answer is that policies that grow the middle class pay for themselves,” Nick writes. “Not in the first year, maybe not over 10 years, but certainly in the long run, because, as Harris recently explained in a speech to the Economic Club of Pittsburgh, the middle class is ‘the growth engine of our economy.’”

I encourage you to read and share Nick’s piece, which unspools one of the most pernicious fictions created by America’s political class. We must refute this lie that the ideal policies rest directly between the two poles of partisan politics. It’s only by investing directly in the majoritarian middle class that we can undo the damage that trickle-down economics has done to our economy.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

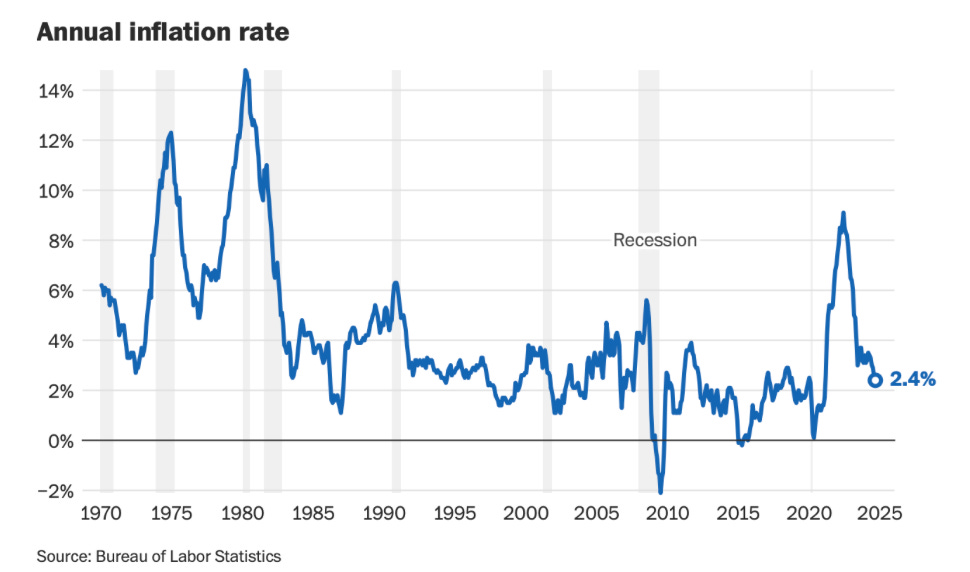

Inflation Eases in September

This morning, the Commerce Department announced that the consumer price index dipped slightly to 2.4%, the lowest annual decline since February 2021. The number came in a little higher than economists’ predictions, largely because food and housing prices increased slightly last month.

“The bulk of September’s monthly increase was driven by a rise in prices for housing and food, which increased by 0.2 percent and 0.4 percent, respectively,” writes Andrew Ackerman in the Washingotn Post. Energy prices fell 1.9 percent over the month, driven by a decrease in gas prices. Prices for used cars and trucks dropped 5.1 percent for the year but increased 0.3 percent on a monthly basis in September after three months of declining prices.”

The dip in inflation is a good positive signal for the Federal Reserve, which will meet to discuss another potential interest-rate drop the day after Election Day next month, and it continues a series of strong economic indicators including good jobs numbers and rising paychecks.

Delivering Big Wins for Workers

The Longshoremen’s strike that I wrote about last week is already fading into memory, thanks to the Biden White House. Just two days after the strike began, Biden praised the East and Gulf coast port workers for reaching a tentative agreement that saw them return to work until at least January while negotiations on a long-term contract continue. Now the union and the alliance have until January 15th to come to some sort of agreement on automation.

“Employers, represented by the United States Maritime Alliance, have offered to increase wages by 62 percent over the course of a new six-year contract,” reports the New York Times. “That increase is lower than what the union had initially asked for, but much higher than the alliance’s earlier offer.”

The Washington Post credits the Biden Administration for working with the union and the alliance to find a resolution months in advance of the strike. The night before the deal was reached, Acting Labor Secretary Julie Su “ slept for less than three hours, staying up on the phone with [Dockworkers union President Harold] Daggett past 2 a.m., then taking a call with the shippers at 5:30 a.m.” Biden’s National Economic Council Chair Lael Brainard and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg also contributed to the end of the strike.

“Today’s tentative agreement on a record wage and an extension of the collective bargaining process represents critical progress towards a strong contract,” Biden wrote in a statement. “Collective bargaining works, and it is critical to building a stronger economy from the middle out and the bottom up,” he added.

Meanwhile, the other two big labor actions we talked about last week are still underway. Boeing and the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers have reached a stalemate, so the strikes at Boeing manufacturing plants in Washington and Oregon will continue, and Stellantis is trying to sue the United Auto Workers to stop the union from going on strike. UAW workers argue that their employer has gone back on several terms agreed to during negotiations earlier this year.

As these unions demand more wages and benefits from their employers, the labor market is still working in their favor. “U.S. employers added 254,000 jobs and the unemployment rate ticked down to 4.1 percent in September, signaling strength in the labor market heading into the height of the election season,” writes Lauren Kaori Gurley at the Washington Post.

“The past several months of steady job growth have been plenty enough to keep the American labor market firmly out of recession territory, economists say, especially as GDP growth remains hardy, productivity is strong and consumers continue to spend,” Gurley explains. “In September, the service sector industry recorded a surge in hiring, according to the report by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. But job gains across most sectors added more evidence that the Federal Reserve can stay on track with gradual lowering of interest rates to ensure inflation doesn’t rear back up.”

And the New York Times explains that many of those jobs are being created at “a record surge” of newly formed small businesses. “Businesses formed from 2020 to 2022 had created 7.4 million jobs by the end of 2022, according to data released by the Census Bureau last month, contributing to the strong rebound in the broader labor market,” the Times reports. “More timely but less comprehensive data suggests that these businesses have continued to add jobs in the past two years.”

This is another example of a middle-out economy in action: When workers in one part of the economy thrive, so do workers in completely different parts of the economy. When Boeing workers have more money to spend, they eat at more restaurants, buy more clothes for their kids, and spring for massages, creating jobs across the economy. In the same way, workers at startups are improving outcomes for unionized machinists at Boeing factories. When the labor market is strong, all workers benefit.

American Medical Care Is World-Class. Accessing That Care Is the Problem.

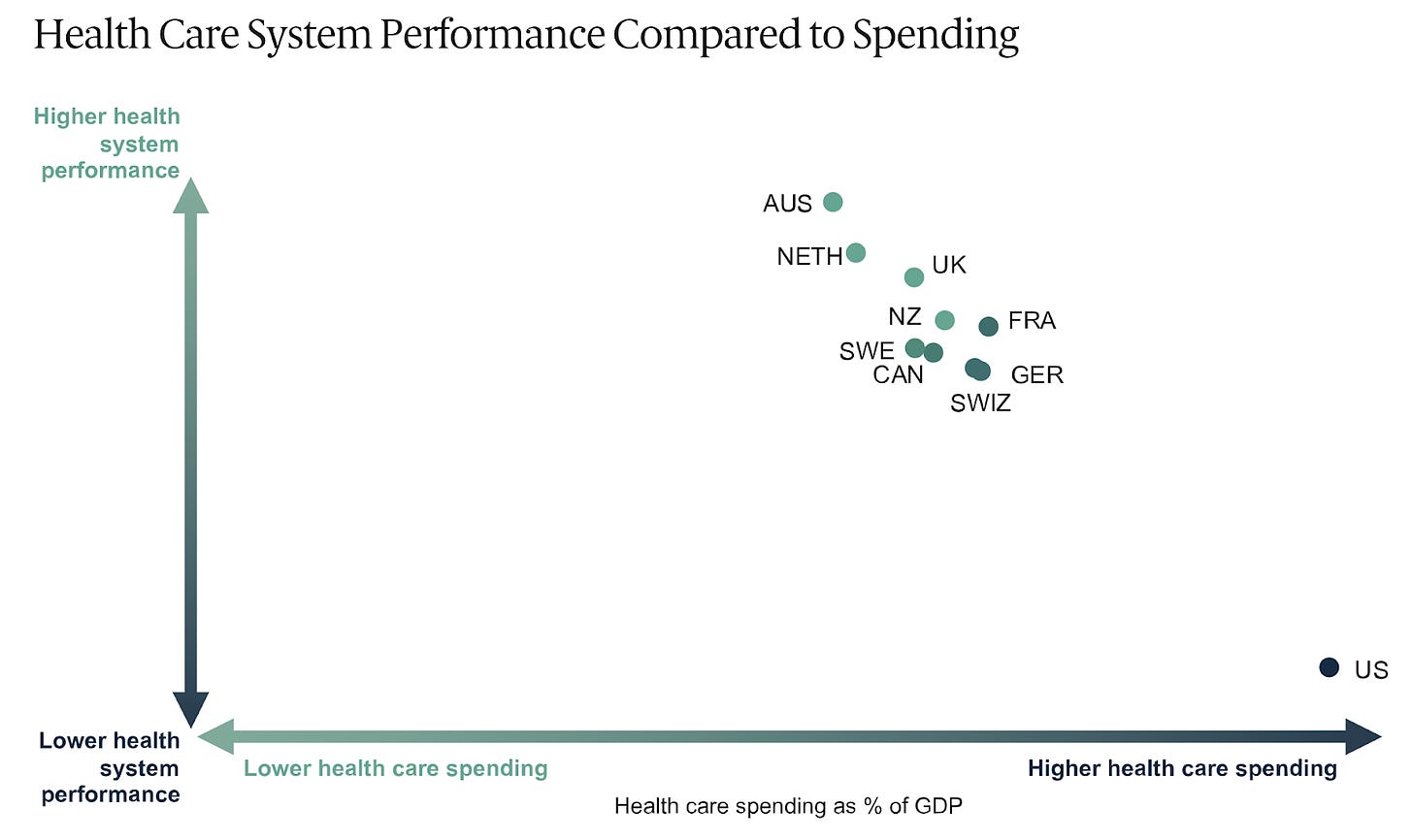

The Commonwealth Fund, an American healthcare watchdog, just issued their eighth annual report comparing the health care systems of 10 nations: “Australia, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.” “We examine five key domains of health system performance: access to care, care process, administrative efficiency, equity, and health outcomes.”

Their findings are, unfortunately, predictable. They report, “in the aggregate, the nine nations we examined are more alike than different with respect to their higher and lower performance in various domains. But there is one glaring exception — the U.S….Especially concerning is the U.S. record on health outcomes, particularly in relation to how much the U.S. spends on health care.”

The summary concludes, “The ability to keep people healthy is a critical indicator of a nation’ capacity to achieve equitable growth. In fulfilling this fundamental obligation, the U.S. continues to fail.”

Of the ten nations, the US comes in dead last in health care system performance, meaning how efficiently it delivers care to patients. It also comes in last on performance compared to spending.

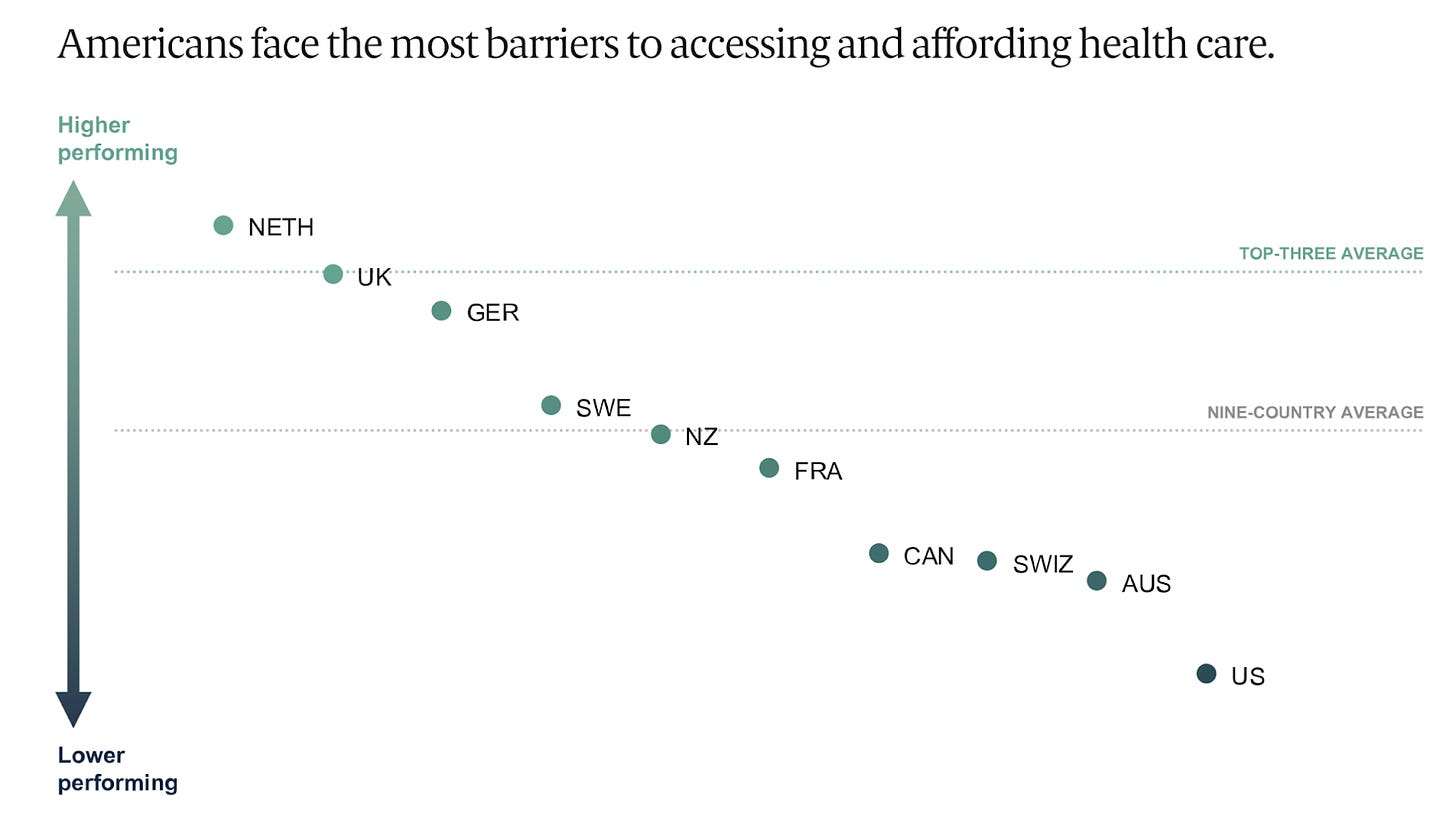

Americans also face the most barriers to accessing and affording health care, and our system is the most unequal of all the nations included in the study. Put more simply, the majority of Americans face tremendous barriers to accessing and affording health care—especially Americans of color and Americans on the lower end of the income scale.

All these low ratings combine into a dire portrait of American health. “The U.S. ranks last on four of five health outcome measures. Life expectancy is more than four years below the 10-country average, and the U.S. has the highest rates of preventable and treatable deaths for all ages as well as excess deaths related to the pandemic for people under age 75,” the report concludes.

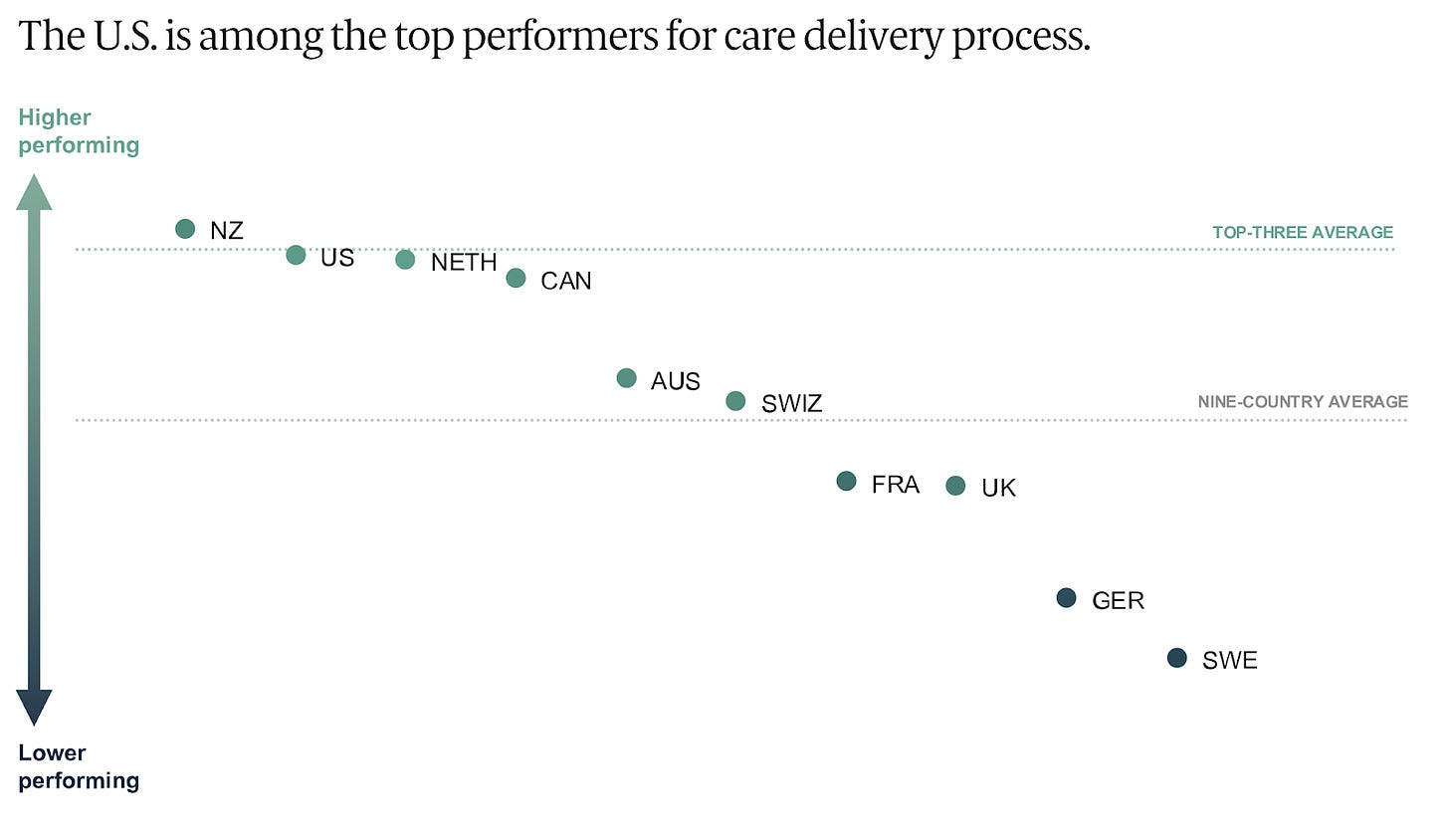

The one area in which the United States leads most of the world, coming in second in the Commonwealth Fund’s report after New Zealand is in “care delivery process,” which the report defines as “whether the care that is delivered includes features and attributes that most experts around the world consider to be essential to high-quality care.”

That is great news—it means that once Americans finally clear the many hurdles of cost, equity, and accessibility that our healthcare system places in their way, the care that American doctors and medical facilities provide is excellent. Our goal, then, should be to remove those hurdles.

Obviously, the Affordable Care Act has immensely improved healthcare access and affordability in the United States, but this report is a reminder that we have a long way to go before our system even matches the global average among our peers.

The report offers a wide range of potential solutions for the US to pursue in order to improve our healthcare system, including investing in the education and training of primary care providers, ending consolidation in the form of hospital mergers and giant acquisitions (including those by private equity firms) in the healthcare space, and big investments in America’s public health programs. There’s a lot more detail in the report, and I urge you to read it in full.

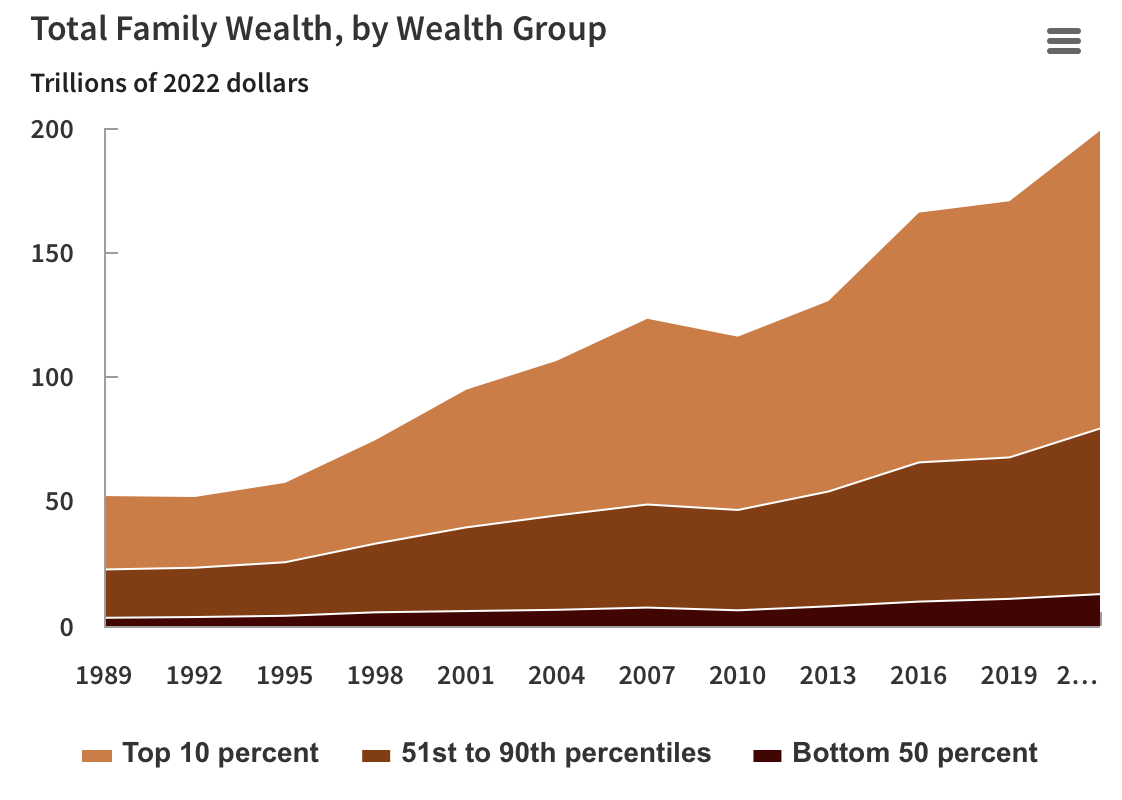

American Inequality, In One Chart

The good news is that a new report from the Congressional Budget Office finds that American household wealth has grown significantly over the past 33 years. “Adjusted for inflation, the wealth held by families in the United States almost quadrupled between 1989 and 2022, rising from $52 trillion (in 2022 dollars) to $199 trillion, at an average rate of about 4 percent per year.”

The bad news is that wealth is distributed very unevenly. “In 2022, families in the top 10 percent of the distribution held 60 percent of all wealth, up from 56 percent in 1989, and families in the top 1 percent of the distribution held 27 percent, up from 23 percent in 1989,” the CBO notes.

“The share of wealth held by the rest of the families in the top half of the distribution shrank from 37 percent to 33 percent over the same period. Families in the bottom half of the distribution held 6 percent of all wealth in both 1989 and 2022,” they conclude. One look at the chart issued with the report shows you how lopsided the wealth distribution has become:

Let’s be clear: This redistribution to the wealthiest families is absolutely intentional. It’s the result of the adoption and implementation of decades worth of trickle-down policies that slash taxes for rich people, deregulate the powerful, and lower wages for everyone else.

The Biden Administration has started to reverse these policies with middle-out economic investments in the vast majority of Americans, but it’s going to take years of sustained middle-out leadership to turn this tide around.

This Week in Middle Out

“The Environmental Protection Agency finalized a rule Tuesday requiring water utilities to replace all lead pipes within a decade, a move aimed at eliminating a toxic threat that continues to affect tens of thousands of American children each year,” reports the Washington Post. The regulation would also lower the amount of lead allowed in drinking water.

Politico reports on the minimum-wage increases that will be on the ballot in states around the country. Some standouts include a vote to increase Massachusetts’s tipped minimum wage from $6.75 an hour to $15, a Missouri wage increase that would also establish paid sick leave, and a $15 minimum wage increase in Alaska that would “prohibit companies from punishing workers for choosing not to attend captive audience meetings, employer-sponsored gatherings that discuss political or religious topics.”

The US Department of Agriculture is “investing in 116 projects across the nation to expand access to a clean and reliable electric grid, safe drinking water and good-paying jobs for people in rural and Tribal communities. Part of the funding…will make water infrastructure in rural areas more resilient to the impacts of climate change and severe weather.”

Wednesday’s episode of The Daily podcast offers a clear-eyed, smart look at how the fight over NAFTA realigned American politics, shifting Democrats away from working Americans and igniting a populist fire in the Republican Party. My one big quibble with the episode is that it doesn’t acknowledge the Biden Administration’s middle-out investment in factories and working Americans, choosing instead to end with Donald Trump’s big talk on trade as a candidate in 2016 and largely ignoring his failure to follow up on those promises as a president.

Manufacturing jobs have finally risen above pre-pandemic levels, reports Emily Peck at Axios. This marks “the first time since the 1970s that the manufacturing industry has recovered all the jobs lost during a recession.”

Vice President Harris this week proposed expanding Medicare to cover home health care, a move which would offer investments for Americans in the so-called “sandwich generation” who are raising children and providing intense care for aging parents. Harris also proposed adding vision and hearing care to Medicare coverage.

Paul Krugman looks at the good economic news of the past few months and concludes that “our success at getting to the good place where we are right now shows that progressive economic policies are, in fact, feasible.”

NPR explains how some states and local communities are stepping up to fill the gap left when Congress allowed the Child Tax Credit to expire.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Professor Zephyr Teachout joins Nick and Goldy this week to talk about Vice President Kamala Harris’s proposals to combat price gouging. Teachout explains the Econ 101 thinking is that the free market will always regulate price distortions because competition will drive prices down. But during the pandemic, she says, “what we saw instead was the same big players were using their dominant position to not only rake in extra profits, but they were scaring away competitors.” She adds that lots of states, including conservative trickle-down bastions like Florida and Texas, have their own price-gouging laws on the books, so Harris’s proposal would simply enhance those laws on the federal level.

Closing Thoughts

As I write these words, our nation’s eyes are turned squarely to Florida, where Hurricane Milton has proven to be one of the worst hurricanes to ever land on American soil. Millions of people are right now going through something unthinkable for most of us, uprooted from their daily lives and living in uncertainty, unsure if their homes and jobs will be there for them when they return after the storm has passed. They’re in all our thoughts right now.

Milton is the second major hurricane to strike the American south in two weeks. We’re still learning the extent of the damage caused by Hurricane Helene, which tore a path through North Carolina in late September. Helene’s wake is still creating repercussions for all of us.

For NPR, reporter Sydney Lupkin reports on a factory “in Marion, N.C., about 35 miles east of Asheville,” which “is owned by Baxter International, and it's the company's biggest plant. It makes IV fluids - sterile water, saline fluids mixed with some carbohydrates.” The Marion factory alone produces 60 percent of the nation’s IV fluids, according to the New York Times.

Helene rendered the factory inoperable when it swept through Marion, flooding it and filling it with mud. Now, “Baxter is limiting orders to prevent panic buying that could make things worse and to make sure that the existing supply of IV solutions is distributed evenly,” Lupkin reports. Baxter predicts the factory will come back online by the end of the year, but they refuse to offer an estimate for how long it will take the factory to return to full capacity. In any case, it will certainly take many months, not weeks, before the Marion factory is completely online.

“One hospital executive told me he was only allowed to order 40% of his usual IV supply,” Lupkin says. “Baxter also sent a letter to hospitals suggesting they reevaluate their IV fluids protocols to make sure they're going to the people who really need them and not being wasted. The FDA says it may look at temporarily allowing imported IV fluids to avoid shortages.”

This factory outage could affect hospitalized Americans across the country. For instance, Lupkin says, “an ER patient might be given an anti-nausea medication and asked to try to drink Gatorade or Pedialyte to hydrate rather than getting an IV.”

The Marion factory’s closure spotlights a significant failure in our medical supply chains. How is one factory responsible for producing a necessary medical product for six out of ten Americans who need IV treatments? The Times explains that “this episode aligns with the factors experts list as those that amplify the risks of disruptions to patients: The products are cheap, giving few suppliers incentive to make competing products. Given sterility requirements, the barriers to enter the field are high.”

In other words, the free market has failed the American medical system yet again. Without competition in this space, one manufacturer essentially has monopoly power over an important piece of the American health care system, and that harms all of us. Given the fact that climate change is increasing the number of once-in-a-century weather disasters to practically every year—even in locations like Appalachia which were previously considered “climate sanctuaries” that were unlikely to see flooding and other climate-caused disasters—we can’t afford to allow concentration to put all our eggs in one basket anymore.

The Helene disaster should inspire our leaders to consider making middle-out investments in strengthening the medical supply chain and increasing competition by building multiple factories that make necessary medical supplies. Doing so would create jobs, better prepare us for an uncertain future, and, most importantly, save American lives.

Onward and upward,

Zach