Friends,

We’ve talked in the past about the unreliability of polls that ask Americans to rate their feelings about the economy and economic issues. People’s perceptions of the economy and their own economic circumstances have always been complex but the dynamics are wonkier than ever.

For one thing, most people don’t feel rich—no matter how much money they have. This Bloomberg report, for instance, points out that many Americans wealthy enough to rank in the top ten percent of earners feel like they’re just scraping by: “In a nationwide survey of over 1,000 objectively wealthy Americans — defined in this case as making at least $175,000 a year, roughly the amount required to crack the top 10% of US tax filers — a full quarter told us they were either ‘very poor,’ ‘poor,’ or ‘getting by but things are tight.’ Half described themselves as just ‘comfortable.’”

According to this Bloomberg poll, there’s even a group of households earning more than $5 million per year who consider themselves “very poor, poor, or getting by.”

If being in the top 10% doesn’t give you a feeling of economic security, imagine how Americans in the other 90% must feel.

When it comes to feelings about the economy, partisanship affects how someone judges the economy. Members of the party that currently sits in the White House have always tended to feel better about the economy than the party out of power. But there are some new and more dramatic swings, particularly for Republicans.

Conor Sen highlighted a big partisan gap this week in a new Quinnipiac economic poll of Republicans. “57% of Republicans describe their personal financial situation as excellent or good, but 77% of those same Republicans say the economy is getting worse, and 95% of Republicans disapprove of the way Joe Biden is handling the economy,” Sen writes.

Every poll shows this partisan disparity on the economy. Even the University of Michigan’s gauge of consumer sentiment is affected.

According to Jennifer de Pinto, CBS News recently ran a poll asking Americans how they felt about the economy. She writes, “52% of Democrats said the economy is good, compared to just 15% of Republicans who said so.”

That’s quite an astounding gap—especially when you look back at the history of the poll. “In CBS News polls conducted throughout the 1990s, the economy rating gap between the Democrats and Republicans — the difference between the percentage of each saying good — averaged 11 points. That average has more than doubled to 30 points since then,” de Pinto writes.

There’s always been a bit of a partisan gap on economic issues, but the gap grew much bigger when we entered the hyper-partisan “red-state, blue-state” era of the 2000s. On the Republican side, this gap seemed to completely detach from the economic reality around 2015—which, perhaps not coincidentally, is the point that Donald Trump entered the presidential race. In fact, this partisan divide has grown so large, and is so lopsided on the Republican side, that it now risks making polls rating the state of the economy essentially useless.

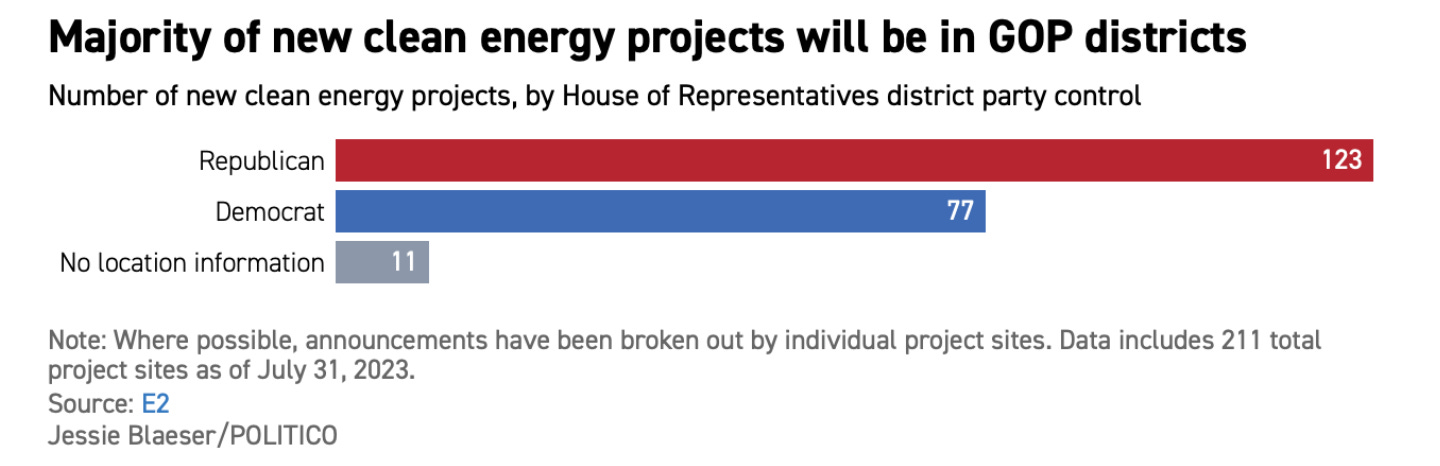

You can see the real-world impacts of this weaponized partisan economic gap in a recent Politico story that collects anecdotes from red states benefiting from President Biden’s big investments in manufacturing. Even though most of those clean-energy projects are in red states…

…some of those red-state residents are rejecting the reality of the economic benefits pouring into their communities. The most extreme example is an interview with a Trump supporter named Bill McAnally, who owns a diner in Inola, a community that is about to see a huge influx of manufacturing jobs:

“It’s a great deal,” said McAnally, 68, since Enel, through its affiliate 3Sun USA, expects to generate 1,000 manufacturing jobs in 2025. “All it does is help my business.”

But when told by a reporter that Enel plans to take advantage of tax credits included in Biden’s climate law, McAnally abruptly changed his tune.

“I don’t support it now,” he said. “The federal government doesn’t need to get involved. We all support bringing in green, but we don’t want to give them all this free money.”

Let’s not take any of this too seriously. The Politico story is basically a series of cherry-picked anecdotes of the most extreme examples of hyperpartisanship. A tiny handful of obsessive Republicans might reject bigger paychecks just because a Democrat helped create their job, but most people will happily take the higher wages, and celebrate all the spending that those wages create in the community. That’s why Republicans who rejected the Biden Administration’s spending bills happily embraced the benefits that those spending bills produced in their own communities.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The Question of the Moment: How Good Is the Economy Right Now?

“It’s no secret the United States appears to have sidestepped economists’ worst fears of a recession,” writes the Washington Post’s Abha Bhattarai, “But now the summer of 2023 is shaping up to be a period of unexpected expansion. With unemployment near 50-year lows, inflation edging down and wages rising faster than prices, businesses and families are still spending: Orders for American-made goods spiked in June and fresh data this week shows that retail and restaurant sales climbed for the fourth straight month in July.”

In fact, this week the Atlanta Fed shocked the economic world by estimating the Gross Domestic Product will grow by an eye-popping 5.8% in the third quarter of 2023:

The GDP might be climbing because American manufacturers are manufacturing again. “Investment in construction of manufacturing facilities has doubled from 2021 to 2023, compared to an increase of a mere 2 percent from 2017 to 2021,” notes the Roosevelt Institute. “The contribution to GDP from manufacturing construction is the highest since 1981, according to the Council of Economic Advisers, while the overall levels of inflation-adjusted private investment in manufacturing are the highest since modern records began in the 1950s.”

We need to insert a couple of our standard caveats in big bold print here: First, we shouldn’t trust positive predictions any more than we trusted the negative predictions from mainstream economists earlier this year. And second, GDP is a flawed measurement of the economy which measures the health of the wealthiest people and corporations. It doesn’t always capture the economic experience of working Americans.

But the fact that retail sales continued to grow at a rapid clip last month is very encouraging. It shows that consumers feel relatively secure about their personal finances, and their consumer spending is also a good sign for the creation of jobs in the months ahead.

A few warning lights are blinking. For one thing, student loan payments are set to resume soon, which is sure to diminish spending and increase economic anxiety among low-wage workers with student debt. And for another thing, the Fed’s campaign of high interest rates are making mortgages too expensive, and Millennials are falling behind previous generations in terms of home ownership, which is the way that most families accrue and pass on generational wealth. We also can’t forget that gasoline and grocery prices are the economic indicator that most people interact with on a weekly basis. If those prices continue to rise, as they threaten to do right now, millions of Americans will feel the pinch.

Even though many of our leading institutions have changed their economic outlooks from stormy to sunny, our elected leaders can’t lose sight of their goals here: They need to be creating, promoting, and passing policies that lower costs and raise paychecks if they want to keep up all this good momentum.

Workers Continue to Make Impressive Gains

Our friends at the Center for American Progress made a video explaining how the workers at a Georgia school bus manufacturing facility took advantage of President Biden’s green-energy investments as a moment to unionize:

Last week, I wrote about how, in this Hot Labor Summer, one union victory seems to inform the next in a virtuous cycle of worker gains. We can expect a lot more workers to look at the $170,000 annual total compensation (including wages and benefits) secured by UPS drivers in their recent union negotiation as a big inciting event for many workers—especially in the delivery/warehouse space.

But despite these recent high-profile victories, unionization is still near an all-time low. Government should be advocating for the vast majority of workers who don’t belong to a union. Jessica Goodheart at Capital and Main writes about a newly revived commission in California that could help raise wages for workers who have been left behind for too long.

“The Industrial Welfare Commission, originally established in 1913 to regulate workplaces that employed women and children, has powers that rattle corporate interests, including issuing wage increases,” Goodheart writes. “Lawmakers specifically wanted to ensure that the commission would not stray from its purpose and become a management ally. The bill, AB 102, that provided $3 million in funding for the commission requires that it issue orders that strengthen, as opposed to weaken, labor protections.”

The Financial Industry Still Needs Regulation

Jordan Miller at the Roosevelt Institute sounds the alarm bell on a new development in the financial industry: Almost a year after the cryptocurrency industry imploded in remarkable fashion, many financial institutions have started to invest peoples’ retirement funds in crypto.

“In June 2023, Charles Schwab, Fidelity Digital Assets, Citadel Securities, Sequoia Capital, and a variety of other high-profile founding partners, announced they were teaming up to invest in EDX Markets,” Miller writes. These big-name institutions control trillions of dollars that Americans have invested toward their retirement, and now they’re putting billions of those funds into a crypto exchange.

“Letting institutional investors place risky bets with clients’ money without clear accountability or robust regulation could lead to a financial disaster,” Miller writes. “This type of gamble is reminiscent of elements of the Great Recession, when it was assumed that the exposure to risky investments was contained within the trading desks of large banks; but as it turned out, these risks had also spread to many other components of the financial system.”

Miller warns that this move gives EDX a “veneer of respectability” that could serve as a green light to other financial institutions to invest in the crypto exchange. At the very least, Congress should be investigating this decision to see if Schwab, Fidelity, and the rest have done their due diligence into EDX’s stability. And hopefully, we’ll soon see some sturdier regulations on the cryptocurrency space as a whole, because it’s clear that not even a humiliating collapse and the imprisonment of prominent crypto leaders isn’t enough to wipe the industry out entirely.

Meanwhile, the banking industry continues to demonstrate the need for tighter regulations of their own. After Silicon Valley Bank collapsed at the beginning of this year, Axios reports that half of the big corporations in this country “changed the banks holding their cash and short-term investments after SVB collapsed, per a Clearwater survey of 155 treasurers managing more than $500 million.” What’s behind that huge transfer of corporate savings? After Roku and other companies were revealed to have hundreds of millions of dollars just sitting in accounts at SVB, other corporations didn’t want to be caught with their pants down after a potential banking collapse. Clearly, corporations have been complacent with their savings for too long.

And the banking industry in general still hasn’t recovered the appearance of stability that it enjoyed before the SVB collapse. Moody’s has already cut the credit ratings of ten small-to-midsize American banks and six bigger banks this month, and Fitch warns that it may downgrade banks, including industry giant JP Morgan Chase, which would require those banks to “pay investors more to buy their bonds, which further compresses profit margins,” as well as possibly locking some banks “out of debt markets entirely” and “trigger[ing] unwelcome provisions in lending agreements or other complex contracts.”

In other words, it could become a lot more expensive to be a bank in the United States, and that affects virtually every American in one way or another. Stronger financial regulations could have prevented bankers from falling asleep at the wheel and throwing their institutions into risk.

Global inequality is decreasing

After two centuries of growing global income inequality, the Gini coefficient, which measures the level of inequality between nations, has dropped steadily over the last twenty years, reports Axios, adding, “That means the world is more equal now than at any point since about 1875.”

It’s important to note that the level of inequality within countries—essentially the gap between the richest citizen of a nation and the poorest—has ticked up over the same time period. (Though these numbers are only updated through 2018 and since the pandemic, in America at least, inequality has finally started to fall for the first time in decades.)

Some will interpret this lessening inequality as bad news for the United States’s global economic leadership, but that’s outdated, winner-take-all economic thinking. Just as it’s good for all restaurants when every dishwasher can afford to eat in restaurants, it’s great news for global trade when the poorest citizens of the world can participate in the economy. Middle-out economics doesn’t just apply to the United States—we can build enough prosperity for the entire human race.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Nick and Goldy answer a few listener questions in a wide-ranging AMA podcast episode. I especially appreciated their response to a listener who asked if she should feel guilty about investing for her retirement in mutual funds, which often profit from rapacious Wall Street behaviors. Goldy’s response really distilled down an important nuance about systemic problems and individual behaviors—on both ends of the income scale. “You are doing nothing wrong by participating in the only system that exists,” Goldy assured the listener, “ just like it’s not Nick’s responsibility to take all of his fortune and give it to the government or spend it himself trying to solve problems unilaterally just because the system is rigged in his favor. What it is Nick’s responsibility to do, which is what he does, is to try to work to change that system so that it works for everybody.”

Closing Thoughts

Now that widespread predictions of a recession have failed to materialize and inflation has slowed down without the widespread layoffs and unemployment that high-profile economists were calling for, it’s a good time to re-examine the mainstream economic response to inflation, to sort out who was right and who was wrong. For the Washington Post, Jeff Stein looks at comments made by former Obama economist Larry Summers, who was the biggest cheerleader for widespread layoffs in order to bring inflation down. Summers, for his part, is still hiding behind the fact that inflation hasn’t hit the 2% rate that many economists have decided, for no real mathematical reason, is the ideal rate for economic stability. (Others argue that 3% is a healthier and more realistic goal.)

Summers aside, the economics profession seems to be entering a rare moment of self-reflection. For instance, in his latest column, Paul Krugman tries to examine why so many economists were so deeply wrong over the past two years.

Krugman correctly says orthodox economists “should ask themselves whether inflation pessimism was in part caused by a form of bias that has had negative effects on a lot of economic policymaking — not partisan bias, but the urge to sound serious by calling for hard choices and sacrifice.”

But I’d argue that the economists were not just trying to “sound serious.” Instead, they were engaged in trickle-down thinking. They believed that the vast majority of Americans needed to sacrifice through massive job losses so that the wealthy few—who mainstream economists incorrectly believe are the creators of economic growth—could rebuild the economy anew.

This was the dominant economic policy after the Great Recession, and it caused the decade-long sluggish economic recovery that ran right up to the beginning of the pandemic. Instead, widespread consumer spending, spurred on by bigger paychecks, encouraged the economy to grow through the inflationary period caused by supply-chain snags, which saved the economy for everyone, including the wealthy few.

Also this week, the Obama Administration’s Economic Council of Advisors Chair, Jason Furman, looked at the lowering inflation rates and strong employment levels and asked, “Do economists need to throw out our models and start over?” Not so fast, he concludes in the next paragraph: “While no macroeconomic theory is perfect, and humility is always in order, a closer look at the data suggests this would be an overreaction.”

So both of these reflections conclude that while many mainstream economists made wrong-headed predictions that often turned out to get the situation exactly backwards, the underlying economic models that informed those economists are still correct and not in desperate need of repair.

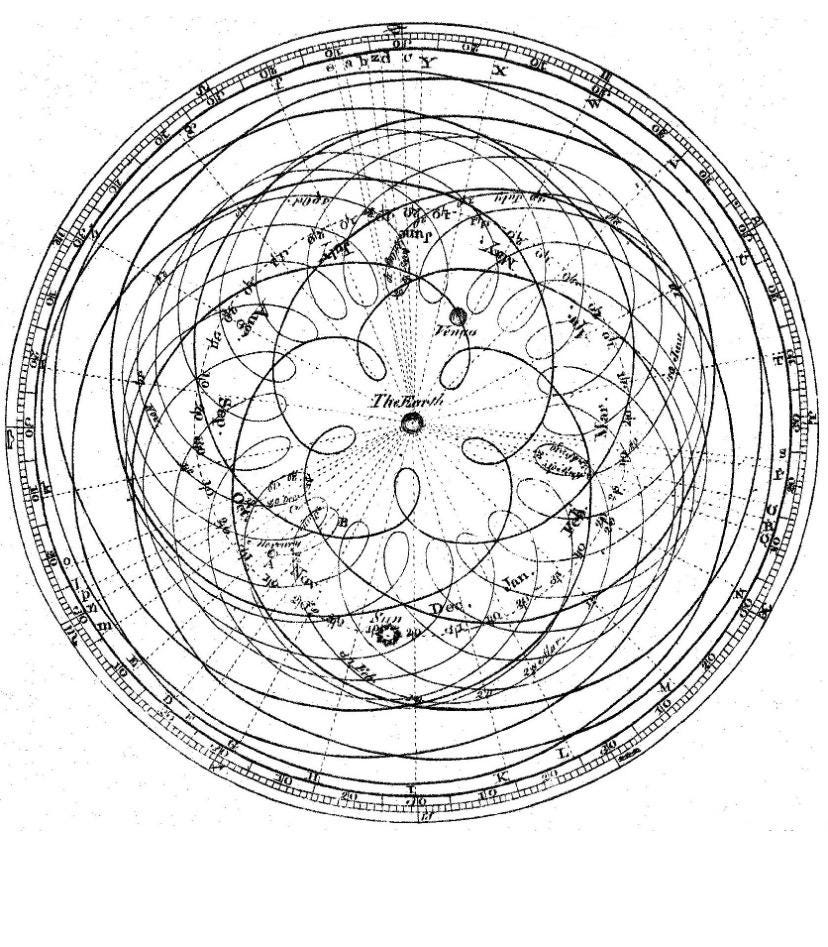

The way that some economists are tying themselves up in knots to prove that their models are still accurate and good is very reminiscent of the Copernican revolution. When Copernicus proved that the Earth revolved around the sun, and not the other way around, the orthodoxy kept building more and more outrageous justifications for why their models were correct, even though the obvious truth was that the earth simply wasn’t the center of the universe. When confronted with Copernicus’s elegant explanation of how the solar system actually worked, the experts of the time instead twisted their argument into more and more complex models, like this:

What we’re seeing now, even from serious and sharp economic thinkers like Krugman and Furman, is an inability to fully accept the idea that the economy is powered by the paychecks and spending of the vast majority of Americans. Instead, they’re still measuring the economy using the old-fashioned neoliberal models that insist economic growth is powered by a handful of the richest Americans and corporations—even as a growing body of evidence proves that the opposite is true.

Change is difficult. It’s a hard thing to reorient your understanding of the universe. You can’t just wake up one morning and shake off decades of training and experience that tells you the world operates in a certain way, just because evidence argues otherwise. But when that body of evidence grows, and when reality continues to follow the contours of the new understanding, the best thinkers are willing to accept change. I believe we’ll see more converts to middle-out economics in the months and years to come.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach