Documenting Inequality

The Pitch: Economic Update for June 8th, 2023

Friends,

Despite the dire predictions of economists, last Friday saw the publication of another amazing jobs report, with 339,000 jobs added to the economy in May. Wages were still up, though they’re not climbing at the astonishing pace we saw over the last year. Paychecks grew by only a third of a percent over April and 4.3% over last May.

“The hiring numbers suggest that employers remain eager for workers even in the face of high interest rates and economic uncertainty,” writes Sydney Ember at the New York Times. “Many are still bringing on employees to meet consumer demand, especially for services.”

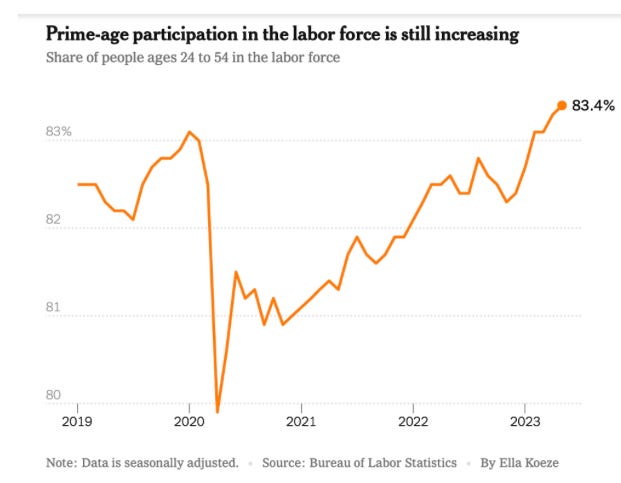

By many metrics, we’ve grown beyond comparing our current economic signals to pre-pandemic times. In fact, labor force participation for people ages 24 to 54 last month hit levels unseen since 2007—before even the Great Recession.

And the job market is strong for younger workers, too. “Teen summer wages have risen in recent years, even after accounting for inflation,” Ann Carns writes for the New York Times. Last summer, the median hourly pay for teenagers rose to $14, from $11.50 in 2019.

Trickle-down prophets of doom like Larry Summers continue to announce that millions of Americans need to lose their jobs to preserve the health of the economy as a whole. But jobs have been surging since the economy reopened from pandemic lockdowns, and while they’re not being created at the same rate as they were in those early days, the monthly jobs reports have slowly and steadily eased down from “historically exceptional” to merely “much better than average.” And to be clear, these working Americans are holding our economy aloft, despite rampant price increases caused by greedflation.

There’s still much to do. Wages must continue to grow to overcome decades of paycheck stagnation, and prices need to continue to come down so that workers can finally feel the benefits of those higher wages. The exciting part is that most Americans know that workers need a raise. A new Data for Progress study finds that the vast majority of Americans support raising the minimum wage to $20 per hour:

Polling also finds people, regardless of party affiliation, believe that “a typical American needs to earn $26 an hour to have a decent quality of life.” It’s clear that the strong job market is emboldening Americans to reassess the value they’re bringing to their employers after decades of vast and growing income inequality. With an election year around the corner, it seems clear that any politician who promises to prioritize the paychecks of working Americans is likely to ride into office on a wave of voter approval.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

While Corporations Jack Up Prices, Will the Fed Make Workers Pay the Bill?

For the New Yorker, Zachary Carter profiles an economist named Isabella Weber, who withstood a tremendous amount of ridicule and derision from mainstream economists when she proposed that inflationary price increases were largely happening due to corporate price-gouging.

To Weber, people like [Larry] Summers were looking at the situation from the wrong side. The focus ought to be on sellers, not buyers. The pandemic had upended global supply chains, making it harder for corporations to acquire the stuff they needed to make their products. This should have squeezed their profit margins. Instead, as the economy began opening up, corporate profits were wildly outpacing growth in consumer spending power.

But in the year and a half since Weber became the subject of near-universal scorn, a funny thing has happened: The mainstream media has finally started to recognize greedflation as a leading factor for the price increases that we’re all paying at grocery stores, and Weber has transformed from a pariah into an expert. Weber is taking the moment to spotlight legislation that combats price-gouging. She’s particularly interested in one proposal from the New York attorney general’s office, which Carter says…

…would draw particular scrutiny to price increases of ten percent or more during a period of “abnormal market disruption.” Critically, this threshold would apply not only to consumer prices but also to price increases further up the supply chain. If such a disruption caused a baby-formula shortage, for instance, retailers could be fined for raising the price of baby formula on the shelves, and baby-formula producers could also be sued for raising the wholesale price charged to retailers.

Even though experts around the world are now beginning to understand that corporate greed, not bigger paychecks, are the main contributor to inflation, the Federal Reserve continues to stubbornly and mistakenly blame workers for higher prices—and it’s raising rates with the intent of shrinking paychecks and deflating the job market.

Due in large part to those high interest rates, 2023 has delivered the largest number of corporate bankruptcies since the tumultuous post-Great Recession year of 2010.

Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times tries to read the tea leaves on the Fed’s next decision, and she finds a consensus among bankers that they may “skip” another interest-rate hike this month. But the Fed mistakenly continues to point to the fact that more Americans are working and taking home bigger paychecks as a sign that interest rates should continue to rise.

And meanwhile, despite the fact that Americans are hard at work, CEOs and bankers continue to forecast a recession that’s just around the corner and will arrive any day now. (For the record, that recession has been consistently “around the corner” since 2021, when the job market just started coming back to life.) These panicked cries of impending doom—which give cover for businesses to shrink wages and lay off workers while profits continue to rise—have long since passed beyond the realm of credulity and into ridiculousness. This week’s prediction of economic disaster from a captain of industry actually made me laugh out loud when I first saw it on Twitter:

If a non-recession recession falls on the economy, does it make a sound? For the Wall Street Journal, Sarah Chaney Cambon explains “Why the U.S. Remains far from Recession,” mostly crediting America’s strong workforce for the economy’s health. That article ends with a very telling paragraph: “Economists surveyed by The Wall Street Journal in April put the probability of a recession at some point in the next 12 months above 50%. But they have said that since October, and the recession appears no closer.”

As if in response to the above cheery economic take, Gwinn Guilford at the Journal argues that we’re on the verge of something called a “full-employment recession,” noting that while workers are still on the job, their productivity has declined. Timothy Noah at the New Republic tackles Guilford’s claims directly, arguing that if employers want to see productivity increase, they can pay workers more. Workers who make more money are likely to stay at jobs longer and be more productive.

Frankly, all these “full-employment recession” and “non-recession recession” claims feel like the desperate work of a status quo scrambling to come up with reasons not to raise the paychecks of workers.

Rebalancing Power in the Workplace

Kellen Browning writes for the New York Times that a decade-old push to frame “gig work” like driving for Uber and food delivery apps as a positive development for workers seeking flexibility has run out of gas. Browning notes that striking screenwriters in Hollywood are demanding more guaranteed schedules from their employers, and arguing that studios can’t just “employ us one day a week like we’re Uber drivers.”

The “gig economy” now has become shorthand for a lopsided, exploitative relationship in which the employer demands odd and unpredictable hours from workers and then declares the odd and unpredictable hours to be a benefit for the worker—all in exchange for lower pay and little to no benefits.

Another uneven business relationship has been undergoing a shift in perception in recent years. Owning and operating a franchise used to be seen as a ticket into the middle class, but Michael Corkery writes that corporations have made it impossible for franchise owners to get ahead. “There has been rising concern about whether franchisees need more protection in their contracts with franchisers,” Corkery writes. “That concern has found a sympathetic ear in the Biden administration and in several state legislatures, and has resulted in multiple proposed limits on franchisers’ powers.”

Meanwhile, other state leaders are working hard to strip workers of protections and give more power to employers. Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds, at the end of May, signed a bill into law rolling back child labor protections that would make it easier for employers to force workers as young as 14 into late-night shifts and jobs in dangerous workplaces like industrial laundries and “facilities manufacturing or storing explosives or articles containing explosive elements.” And The American Prospect’s Harold Meyerson notes that a bizarre Supreme Court ruling against a cement-mixer drivers’ union could make it easier to send striking workers back to work.

But other states are working hard to rebalance the employment dynamic so that the game isn’t rigged toward employers and away from workers. The Guardian’s Steve Greenhouse celebrates a package of laws which passed in Minnesota that establish “paid family and medical leave, prohibits non-compete clauses, bars employers from holding anti-union captive audience meetings, and strengthens protections for meatpacking workers and Amazon warehouse employees.” (I’d like to note with not a little bit of pride that my home state of Washington passed many of those same protections over the last decade.)

And a bill in New York state could protect workers in nail salons, who are regularly exposed to toxic chemicals in the daily course of their work. “It would create a council made up of workers, employers, and public representatives that would work with the state Department of Labor to oversee minimum workplace standards and shape future industry policy,” writes Prem Thakker. “It would also crucially establish an independent committee of experts, overseen by the labor commissioner, to establish a minimum pricing model for nail services in the state, to ensure competing businesses aren’t stuck in a pricing race to the bottom.”

In combination with the renewed discussion about anti-price-gouging laws, it’s interesting to see government taking more of an interest in pricing as a regulatory lever. For so long, economists and leaders have bought into the trickle-down fiction that the free market perfectly establishes prices, but the past two years of greedflation has proven that perhaps the market doesn’t know best when it comes to pricing goods and services.

Is Marketcrafting the Next Big Regulatory Revelation?

America’s food system is currently being throttled by monopolies. Stacy Mitchell writes for the New York Times that giant grocery store chains are driving up prices across the industry. “Major grocery suppliers, including Kraft Heinz, General Mills and Clorox, rely on Walmart for more than 20 percent of their sales,” Mitchell writes. “So when Walmart demands special deals, suppliers can’t say no. And as suppliers cut special deals for Walmart and other large chains, they make up for the lost revenue by charging smaller retailers even more, something economists refer to as the water bed effect.”

Meanwhile, America’s pork producers have oversupplied the market. An Econ 101 producer would tell you that an overabundance of pork should result in lower prices for consumers, but that hasn’t happened. Instead, while retail prices of pork remain high, hog farmers are abandoning their operations, and big agriculture firms like Smithfield are closing whole sow farms in an effort to reconfigure their supply chains. Domestic consumer demand for pork has declined, too, because “the end of pandemic-era food-stamp benefits earlier this year also has cut into U.S. shoppers’ pork purchases.”

Thankfully, our leaders are acting now to stop other industries from growing to monstrous size and swallowing markets whole. The Securities Exchange Commission has sued Binance, the world’s largest crypto exchange, for allegedly “placing investors’ assets at significant risk” by mismanaging billions of dollars in customer funds. The SEC is also cracking down on Coinbase, the United States’ largest crypto exchange.

And while new and erratic industries like crypto seem like easy targets for regulatory agencies, even well-established companies like those that make up Big Oil are undergoing a new level of scrutiny. Lawsuits filed around the country are trying to hold oil companies responsible for the widespread damage of the climate crisis. Next Monday 16 young Americans, ranging in age from 5 to 22, will take the state of Montana to court over its pro-fossil-fuel policies, which the young people argue are endangering their future.

Speaking of young people, David Dayen warns that the resumption of student loan payments at the end of the summer is an “oncoming train wreck.” Assuming that lenders can navigate the logistical snarls inherent to restarting millions of payments all at once, those payments will also interfere with the budgets of millions of workers around the country, potentially throwing many into dire financial straits. Dayen offers another path for President Biden to forgive those debts if the Supreme Court rejects his current path of debt forgiveness as pandemic relief.

But we don’t have to leave regulation in the hands of the courts. Chris Hughes and Peter Speigler applied a new word to define how the Biden Administration could grow a green energy economy from the middle out. The word is “marketcrafting,” and it covers a variety of approaches that leaders can take to use public policy to shape private industry practices.

“They are marketcrafting rather than merely market-affecting because they alter foundational decisions about what market actors do through the use of rulemaking, public investment, or competition policy, among others,” Hughes and Spiegler write. “Policymakers engineer markets, harnessing their power to accomplish a collective good.”

For the Democracy Journal, the authors continue the conversation: “Marketcraft encompasses a wide range of state action. It includes large-scale public investment programs like those supporting the CHIPS and Science Act or the New Deal-era Tennessee Valley Authority, as well as the creation of public options as alternatives to private provision of goods and services, like Medicare and the U.S. Postal Service.”

This means when it comes to progressive policies like employer-provided quality childcare and livable wages, the government can both lead by example and also incentivize employers to follow government’s lead in order to access federal and state investments.

Regular readers of the Pitch might not be surprised by any of this. We’ve already seen this technique in the form of the Biden Administration’s CHIPS Act and other green-energy initiatives. But it’s not just enough for a leader to do something meaningful—if they want to truly affect policy for future administrations, it’s important to put a name and guiding philosophy on the practice. So, marketcraft it is.

Thinking about marketcraft as a philosophy of governing also changes the way we think about regulations. Ask the average American and they’ll likely describe regulations as a set of prohibitive laws governing how industry acts. By leading through example and by shaping the way industry achieves their goals by incentivizing positive societal outcomes, marketcraft expands the perception of what regulations can do, and how regulation can achieve results. I don’t know about you, but I do love a good rebrand.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to ourMedium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

On this week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics, filmmakers Sean Claffey and Dave Pederson join Nick and Goldy to discuss their new documentary exploring the American crisis of wealth inequality, Americonned.

Closing Thoughts

On June 13th, the film Americonned will be available to rent and own on VOD platforms everywhere. It’s a documentary that looks directly at the growing crisis of wealth inequality that has been plaguing the nation for the past 40 years. The film features a wide slate of experts, ranging from labor organizer Chris Smalls to Labor Secretary Marty Walsh to SEIU Local 87 President Olga Miranda to Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer, about how corporations and the powerful have managed to seize control of the levels of power in order to further concentrate their wealth and power—at the expense of trillions of dollars that used to belong to the working and middle classes.

Here’s a trailer for the film:

If you’d like to learn more about why filmmakers Dave Pederson and Sean Claffey made Americonned, you can listen to this week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics, which features a wide-ranging interview with them about the ideas behind the film. The process of documenting income inequality stretched thousands of miles across 13 states, and it consumed years of their lives.

In that episode, Pederson recounts that he was especially moved when his research revealed all the real-world impacts of this inequality. Those shrinking paychecks have disastrous effects in the lives of Americans: “We see it in the news. Suicides are up. Drug abuse is way up. Drug overdoses are way up. These are all related, this has real effects on people, and they are suffering on a daily basis,” Pederson explains.

Speaking as someone who reads and listens to a variety of articles, podcasts, and books about income inequality almost every day, something about the visual medium conveys that human cost in an especially compelling way. Good documentaries—by which I mean films that look at an issue from a variety of perspectives using firsthand accounts—are a great way to bring people into a conversation.

If you have been trying to convince your friends and family to become more involved in the economic conversation, I urge you to host a screening of Americonned at your home, or bring them to one of the screenings happening around the country this month. We can always use more people to fight against inequality, and this documentary provides a unique opportunity to recruit your social circle to the cause.

And if your friends and neighbors like Americonned, be sure to recommend The Pitch and our podcast Pitchfork Economics as outlets where they can learn more about who gets what and why.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach