Friends,

Much has been written about the “vibe shift” and the remarkable rhetorical transformation on display in last week’s Democratic National Convention, with a slate of younger politicians from around the country stepping into bigger roles within the national party. On the first evening of the DNC, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez made the case for middle-out economics by delivering the kind of progressive economic sentiment that has become her trademark.

“In Kamala Harris, we have a chance to elect a president who is for the middle class because she is from the middle class. She understands the urgency of rent checks and groceries and prescriptions,” Ocasio-Cortez said.

Later, she explained that America’s economic strength comes from the middle out, not the top down. And she argued that middle-out economics is patriotic. “You cannot love this country if you only fight for the wealthy and big business,” Ocasio-Cortez said. “To love this country is to fight for its people, all people, working people, everyday Americans like bartenders and factory workers, and fast food cashiers who punch a clock and are on their feet all day in some of the toughest jobs out there.”

But while middle-out economics received dozens of shout-outs from many talented young leaders, I want to call attention to a couple of speeches by Democrats who have been in the public eye for years. Let’s start with Delaware Senator Chris Coons, who introduced his friend President Biden on Monday night at the DNC.

After getting his start as a young volunteer for President Reagan, Coons has a record that would be pretty unsurprising for any Democrat who entered politics in the early 2000s—he made his name as a young politician for balancing the budget of Delaware’s New Castle County by cutting social safety net spending. He’s been a strong Democrat on matters like abortion and gun responsibility, but his economic voting record was pretty neoliberal, including voting against a national $15 minimum wage.

That’s why Coons caught my attention during his speech on Biden’s record: “Joe got passed and signed into law the most consequential legislation of any president in 60 years: Helping our veterans, advancing gun safety. cutting prescription drug prices, fighting climate change, rebuilding bridges and broadband, bringing manufacturing back to America,” Coons explained.

But more than just reciting a laundry list of achievements, Coons correctly identified why those policies matter: “Together, Joe and Kamala helped rebuild our economy from the bottom up and the middle out, not from the top down,” Coons said. “And they made our families safer and our country stronger at home and abroad.”

Coons used to treat investments in working Americans as so many neoliberals do: a tradeoff that was ultimately harmful to economic growth. To be clear, this was the widespread belief among Democrats throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Last week, though, Coons demonstrated a real understanding of how the economy actually grows: From the bottom up and the middle out, with investments in working Americans growing the economy for everyone.

Even more important was Wednesday’s speech from former President Bill Clinton. Clinton’s legacy is complicated. But there’s little doubt that he was part of the ascendancy of neoliberalism among Democrats in the 1990s. After campaigning in 1992 with a focus on the middle class, he and his administration made neoliberal choices that left working Americans worse off. He signed free trade policies like NAFTA that gave too much power to corporations and the wealthy, he signed off on welfare reform that stripped investments from those at the bottom of the economy, and his team championed banking deregulations that harmed consumers.

Last week, Clinton showed that his understanding of the economy has evolved. “We’ve got to ask ourselves this question if we’re going to hire a president: Do you want to build a strong economy from the bottom up in the middle out, or do you want to spend the next four years talking about crowd size?”

It’s hard to overstate the importance of this shift. For the last 40 years, Democratic leaders bought into the trickle-down understanding of how the economy grows. Wealth trickles down from the top, the argument went, so it was important to transfer wealth to the already-wealthy, and power to those who were already powerful. Those rich and powerful people would then create jobs that would benefit everyone.

But we now know that the trickle-down argument—as simple as it may sound—was not only wrong, it was entirely backward. And not only do younger politicians understand that working Americans are the source of our country’s economic growth, but the old guard is also coming around to that understanding, embracing the new way of understanding our economy. This is a huge deal, and a hopeful sign for the future of political economy.

In politics, it’s always tempting to question the purity of people who are new to your cause, or to relitigate battles of the past. I believe that in transitional moments like this, it’s important to throw the doors of the tent wide open and welcome new arrivals, rather than heckle them about why it took them so long to arrive. That’s the thing about middle-out economics: There’s room for everyone, and we’re all better for it.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Two Market Manipulation Schemes Caught Red-Handed

The Biden Administration has made progress this week on two cases of big corporations trying to kill competition through market consolidation. Lee Hepner explains in a Twitter thread that the Federal Trade Commission is arguing this week against the Kroger-Albertsons merger, which “would put 41 retail grocery brands, 5,000 grocery stores, 4,000 pharmacies and 700,000 employees under one roof.”

“Competition for workers between Kroger and Albertsons has the effect of driving up wages, benefits, and working conditions for over 700,000 employees,” Hepner explains.

The merger would, if approved, cut annual worker wages by an estimated $334 million. We know this because less than ten years ago, the large grocery chain Albertsons bought the Safeway grocery store chain, and the American Economic Liberties Project found that the purchase was “an unmitigated disaster for competition in the retail grocery market,” closing stores around the country and resulting in the elimination of thousands of grocery workers’ jobs. The Albertsons-Kroger merger, which is much larger than the Albertsons-Safeway merger, would likely have a much greater impact.

And the Justice Department also issued its full charges against RealPage, the software used by corporate landlords to set rent prices in apartment buildings across the United States.

Lindsay Owens on Twitter explains that the charges reveal RealPage “wasn't just a computer program spitting out high prices.” The company also brought together corporate landlords who were ostensibly competing for customers in major metro areas around the country “to swap info and hear lectures on how to ‘push up pricing,’” which sounds an awful lot like collusion to me.

The RealPage software allowed landlords to raise prices by killing competition in local housing markets. It also established a software lever to ensure that prices don’t drop too low. But don’t take my word for it: In the Justice Department’s 100-page charges against RealPage, they quote landlords who praised the software: “"I always liked this product because your algorithm uses proprietary data from other subscribers to suggest rents and terms. That's classic price fixing," one landlord gushed to RealPage.

The report also quotes RealPage's Vice President of Revenue Management Advisory Services explaining that "there is greater good in everybody succeeding versus essentially trying to compete against one another in a way that actually keeps the entire industry down." And in marketing materials, RealPage crowed that the software “helps curb landlords' instincts to respond to down-market conditions by either dramatically lowering price or by holding price when they are losing velocity and/or occupancy” and it also helps landlords profit by “driving every possible opportunity to increase price even in the most downward trending or unexpected conditions."

In other words, RealPage was publicly boasting about its ability to rig the game in landlords’ favor by allowing them to kill competition and jack up prices on customers even in times when rents traditionally decline.

In addition, the Biden Administration continues to push back against corporate consolidation. Just this week, the New York Times reported that both federal officials and the United Steelworkers union are fighting back against a proposed US Steel/Nippon merger that would drive up the price of steel, cut wages for Pennsylvania steelworkers, and generally kill competition in the metal production space.

Two Charts Demonstrate the Power of Investing in Working Americans

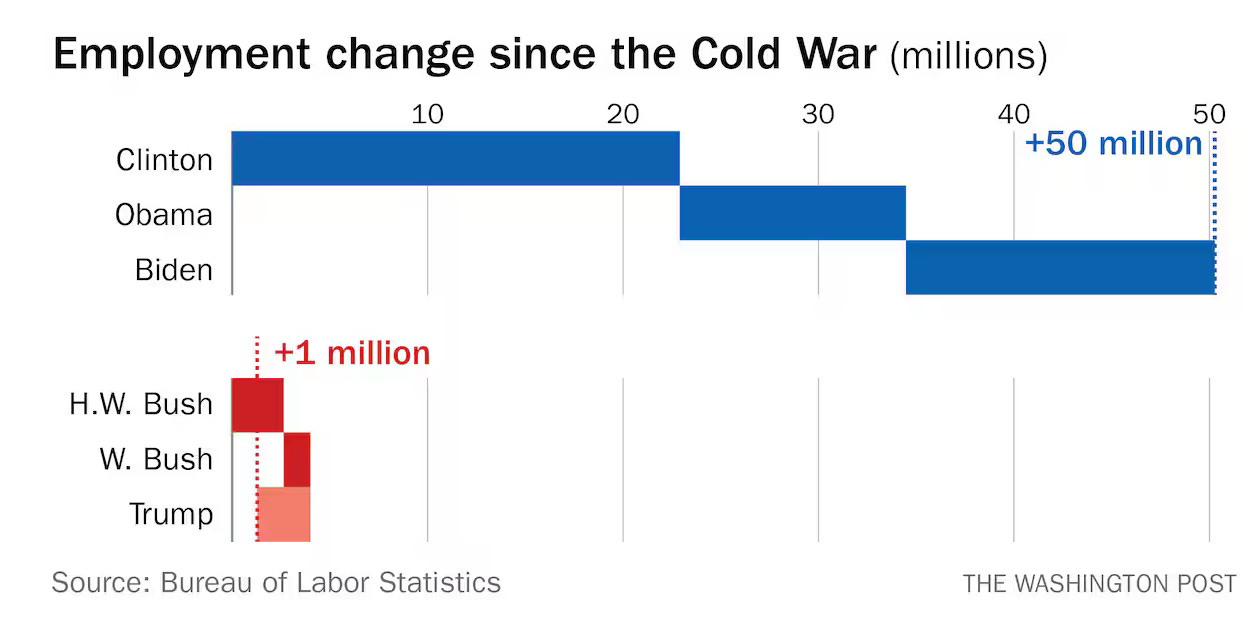

Bill Clinton put the capstone on the middle-out conversion that I mentioned in the introduction when he spotlighted a remarkable metric in his DNC speech. “You’re going to have a hard time believing this, but so help me, I triple-checked it,” Clinton said. “Since the end of the Cold War in 1989, America has created about 51 million new jobs. I swear I checked this three times. Even I couldn’t believe it. What’s the score? Democrats 50, Republicans 1.”

Even the fact-checkers agreed: “The number of jobs created from 1989 through March 2024 — under Republican Presidents George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush and Donald Trump, and Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and Joe Biden — was 50.6 million. Of that number, a bit over 1 million, or about 2.6%, were created during the Republican presidencies,” reported Poynter.

The Washington Post’s Phillip Bump also explored the numbers and found them to be true.

How can this be? Several of the fact-checkers tried to explain this metric away by saying that Democratic presidents tended to take office during economic recoveries from downturns: The George H.W. Bush-era recession, the Great Recession of 2008, the economic downturn during pandemic-era lockdowns. However, that distinction seems to be missing the forest for the trees: Those jobs were created because Democratic presidents invested deeply in working Americans. Republican job growth was anemic because they slashed taxes on the wealthy and cut regulations on the powerful, which harmed the whole economy.

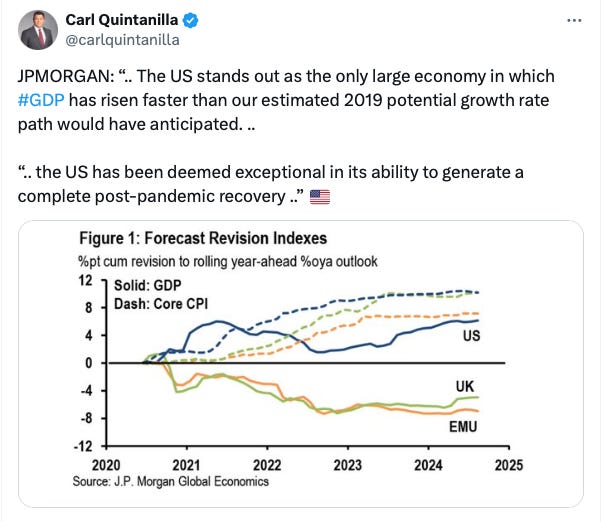

We already know that America’s economy has recovered from the pandemic-era economic decline faster than virtually every other nation in the world. But we’re not only ahead of other nations—our economic growth is even outpacing pre-COVID projections. Here’s what it looks like when your economic policy invests deeply in American workers:

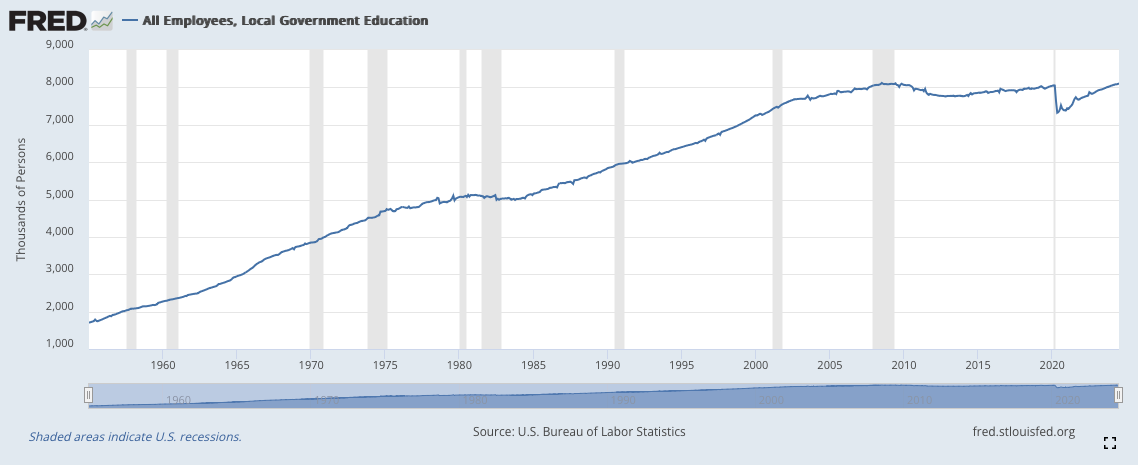

Compare this chart to America’s incredibly slow economic growth after the Great Recession—including some sectors that hadn’t recovered all the jobs lost in 2009 by the time the pandemic began. For instance, America’s public education system still has yet to hire as many workers as it had employed in the months before the economic collapse of 2008.

When you take all this data into account, you have a very clear picture of what happens when you invest recovery funds in the tippy-top of the economy, as we did in 2009, as opposed to widely investing in Americans, as we did in the last three years. The difference is as plain as night and day.

The Economy Isn’t Evenly Distributed

The 19 million jobs that Bill Clinton bragged about the Biden Administration creating weren’t distributed evenly across every municipality. For the New York Times, Ben Casselman and Ella Koeze have compiled a fascinating dataset showing exactly which counties across the nation have gained jobs and which have lost jobs over the past four years.

“As of 2023, more than two in five U.S. counties — 43 percent — still hadn’t regained all the jobs they lost in the early months of the pandemic, according to annual data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics,” they write. “Some of those places were struggling long before 2020. Others had been thriving economically and were knocked off course by an airborne shock few saw coming.”

And the kinds of jobs have changed, too. During pandemic lockdowns, “Restaurants, hotels, movie theaters and other in-person businesses laid off millions of workers, while warehouses and trucking companies went on a hiring spree to meet the surge in demand,” they write. “Those shifts have reversed, but gradually and incompletely: The United States has more truck drivers and fewer waiters, as a share of the work force, than it did in 2019.”

The housing affordability crisis also looks very different in different parts of the country. “The housing crisis has moved from blue states to red states, and large metro areas to rural towns,” writes Conor Dougherty at the New York Times. “In a time of extreme polarization, the too-high cost of housing and its attendant social problems are among the few things Americans truly share. That and a growing rage about the country’s inability to fix it.”

Dougherty travels to Kalamazoo, Michigan to explore how smaller towns in the Rust Belt are adjusting to the higher prices that have swept into their community. And while Kalamazoo, like every other community, has issues with housing supply, Dougherty concludes that “Americans’ wages have fallen so far behind the cost of living that each day more and more families — blue collar and professional, in expensive coastal cities and smaller Midwestern ones — find they simply cannot afford a place to live.”

Where did those wages go? To the pockets of the wealthiest 1% of the economy, which has gotten some $50 trillion richer over the past few decades, thanks to trickle-down economic policies that pull money from the pockets of working Americans. No wonder it’s harder for Americans to afford housing.

There’s also a huge gap between giant corporations and small businesses in America. For the Washington Post, Jaclyn Peizer explains that while large grocery stores are raking in profits from greedflation and saving money on sweetheart deals with distributors, small grocery stores are struggling to stay afloat.

“Though there is no national database for such stores, a dozen business owners and experts who spoke to The Washington Post say their risks have been compounded by the rapid expansion of dollar stores, growing power of big-box retailers and rise of dynamic pricing.”

For many rural areas of the United States, these independent grocery stores are the only source of milk, produce, and other staples. It’s yet another example of why the trickle-down understanding of free markets—in which the most efficient, broadly beneficial solutions always win—does not reflect how the world really works. And it’s another great reason why our leaders should combat corporate consolidation like the proposed Kroger-Albertsons merger.

This Week in Middle-Out

Axios explains that the Treasury Department is likely to be the government agency that eventually establishes regulation of cryptocurrencies, though it doesn’t seem to be moving very quickly. “Treasury has called for more effective oversight of cryptocurrency markets. And it's called for the federal government and Congress to fill regulatory gaps,” Brady Dale writes. “But what it hasn't done, is issue a tone-setting statement that clarifies for other parts of the government either that the industry should be, on balance, fostered or forced away.”

For the New York Times, Jen Harris kicks off a package comparing the economic policies of Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump with a look at the two economic principles that seem to be guiding Vice President Kamala Harris’s economic policy: “call them ‘build’ and ‘balance.’ The first focuses on pointing and shaping markets toward worthy aims; the second corrects upstream power imbalances so that market outcomes are fairer and need less after-the-fact redistribution,” she writes.

And Jason De Parle compares Harris’s and Donald Trump’s anti-poverty plans. Harris, he writes, “backs a $15 federal minimum wage, which Republicans have fought, and is a vocal supporter of programs like subsidized child care and paid family leave meant to help balance work and family.” On the other hand, “Mr. Trump’s poverty plans are otherwise vague, but his record is one of animosity toward the programs Ms. Harris would defend or expand. He sought to remove millions of people from Medicaid and food stamps, many of them low-wage workers. He has sought to reduce the number of people with subsidized housing and raise their rents.”

Binyamin Appelbaum looks at the Harris housing plan. “Ms. Harris’s plan has problems and shortcomings and, because it is an actual plan, it is possible to scrutinize its details and to criticize its choices. But it’s important to maintain a focus on the bigger picture,” he writes. “Ms. Harris has a plan, and Mr. Trump does not. She is open to reasoned arguments and advice, and he is not. If Ms. Harris is elected, there is a chance that we may make some progress on the housing crisis. If Mr. Trump is elected, we will not.”

Ana Swanson explores the dueling visions on tariffs and trade: “Ms. Harris has sought to differentiate herself from Mr. Trump’s trade proposals, which include tariffs of 10 percent to 20 percent on most imports, as well as levies of more than 60 percent on China. Many economists say that level of tariffs would drive up prices for consumers…the left-leaning Center for American Progress Action Fund calculated that the tariffs could increase costs on a middle-income family by $3,900 per year,” Swanson writes. “Ms. Harris has not said much about how she would approach tariffs, including whether she would impose additional levies on China. But Charles Lutvak, a spokesperson for the Harris-Walz campaign, said in a statement that Ms. Harris would ‘employ targeted and strategic tariffs to support American workers, strengthen our economy, and hold our adversaries accountable.’”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

On this week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics, Yannet Lathrop of the National Employment Law Project and prominent urban planning expert Dr. T. William Lester join Nick and Goldy to explore the legacy of the Fight for $15 and to examine where the minimum wage fight may go next.

Closing Thoughts

At Stat, four authors explain how private equity is harming America’s healthcare system. “Using dollops of investors’ cash and massive loans, private equity firms have taken over hundreds of hospitals, thousands of nursing homes, and tens of thousands of medical practices, leaving the hospitals, nursing homes, and practices — not the investors — on the hook to pay off the debt,” they write.

I encourage you to read the whole piece, which digs deeply into the pernicious effects of PE’s so-called “investments” in the industry. “Nationwide, in the two years after a private equity takeover, hospitals lost on average nearly one-quarter of their real estate, buildings, and equipment. That’s equivalent to a $28 million loss per hospital,” the authors write. Even worse, these losses are also taking the form of unnecessary patient illness and misery: “after private equity takeovers of hospitals, patients experienced more falls and more bloodstream infections from their IVs, signals of deteriorating care quality.”

Private equity firms also tend to swoop in and buy as many practitioners as possible in given geographical markets, thereby killing local competition. That’s probably why, “When a private equity company buys a clinic or a doctor’s practice, their prices increase by 20% and the number of visits also rises sharply.”

Some states have laws on the books that prevent giant profit-seeking financial organizations from taking control of medical institutions. But in most of those states, PE firms have exploited loopholes that allow them to take control. That’s why the authors make a firm declaration of the kind of policy solutions this situation requires: “An outright ban on private equity ownership of doctors’ practices is the only surefire way to assure that these companies aren’t pulling medical strings,” they write.

“A similar ban should apply to hospitals and nursing homes, most of which were built with taxpayer dollars channeled through grants, tax exemptions, and capital payments that are folded into Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements,” they conclude. That sounds good to me. It’s hard to make a compelling case for an industry that exists to load up useful, profitable businesses with toxic amounts of debt and saddle customers with poor experiences and rising prices.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach