Friends,

“The Federal Reserve left interest rates unchanged for a third meeting in a row on Wednesday,” wrote Colby Smith in the New York Times yesterday. “The unanimous decision to stand pat will keep interest rates at 4.25 percent to 4.5 percent. Rates have been there since December after a series of cuts in the second half of 2024.”

The Fed’s own press release said that the decision to keep interest rates flat was reached even though “recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace,” with “labor market conditions remain[ing] solid.”

“Inflation remains somewhat elevated,” the Fed noted, and though the organization’s stated purpose is to maintain “maximum employment” and a (somewhat arbitrary) 2 percent inflation rate, the Fed was holding interest rates flat. This was an expected move—most economists expected the Fed to keep things in stasis at the moment due to uncertainty about President Trump’s tariffs.

In fact, the Fed notes in its report that “Uncertainty about the economic outlook has increased further,” and that “the risks of higher unemployment and higher inflation have risen.”

We’ve been writing about the economic uncertainty that American workers and business owners have been feeling since it became obvious that Trump’s many campaign promises to institute a strict regime of tariffs wasn’t just an empty threat. Smith notes in the Times that “Some companies have already started to warn about sluggish sales as consumers have turned much more downbeat about the outlook; the fear is that the uncertainty will further chill business activity.”

The Times staff interpreted Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s statements at yesterday’s press conference to mean that the Federal Reserve would continue to keep interest rates flat until either the tariffs are lifted or economic growth deteriorates and reverses. Since interest rates are the biggest lever of power that the Fed controls, keeping their powder dry until the economy dives or recovers is probably the most prudent move they could make.

But that flat interest rate is bad news for the Americans who are priced out of buying a home because mortgage rates remain remarkably high. And it’s bad news for the Americans who are struggling with credit card debt. All told, that adds up to about a third of all Americans—100 million or so people who have been at least partially frozen out of the economy because borrowing rates have been too high for the last three years.

So now the American people are stuck between a president who is single-handedly threatening to keep prices high through a campaign of exorbitant tariffs on foreign goods and a Federal Reserve that’s keeping interest rates high in an attempt to eventually prevent the economy from tanking if those tariffs do raise prices for most Americans. Nobody in that contest is championing lower prices or raising wages for working Americans right now, and the current spate of terrible approval ratings for the president suggest that the American people understand that they don’t have an advocate in charge.

In his press conference after the Fed’s announcement, Powell made a statement that really summed up what most American workers, business owners, investors, and even elected officials feel right now as tariffs loom over everything: “It’s really not at all clear what it is we should do,” Powell said.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Some Points of Weakness in a Strong Jobs Report

Last Friday’s jobs report continued the multi-year trend of relatively solid labor market numbers, accompanied by a very slow but steady decline in opportunities for working Americans.

“The U.S. labor market added 177,000 jobs last month, outperforming expectations for about 140,000, and the unemployment rate held steady at 4.2%,” wrote former Biden White House chief economist Jared Bernstein in his indispensable newsletter. But when you view the growth of worker paychecks on an annualized quarterly basis, “there’s some evidence of slower wage growth,” Bernstein writes. “Hourly wages were up 2.6% by this measure, the lowest since 2021, and have, as the figure shows, been trending down,” meaning that workers have been getting smaller and smaller raises since the huge spike in pay that we saw during 2021.

Paychecks are the most underrated economic metric, of course, because those worker paychecks are what create jobs in local economies. If those paychecks aren’t growing in a time when costs and expenses are rising, that’s a bad sign for economic growth overall.

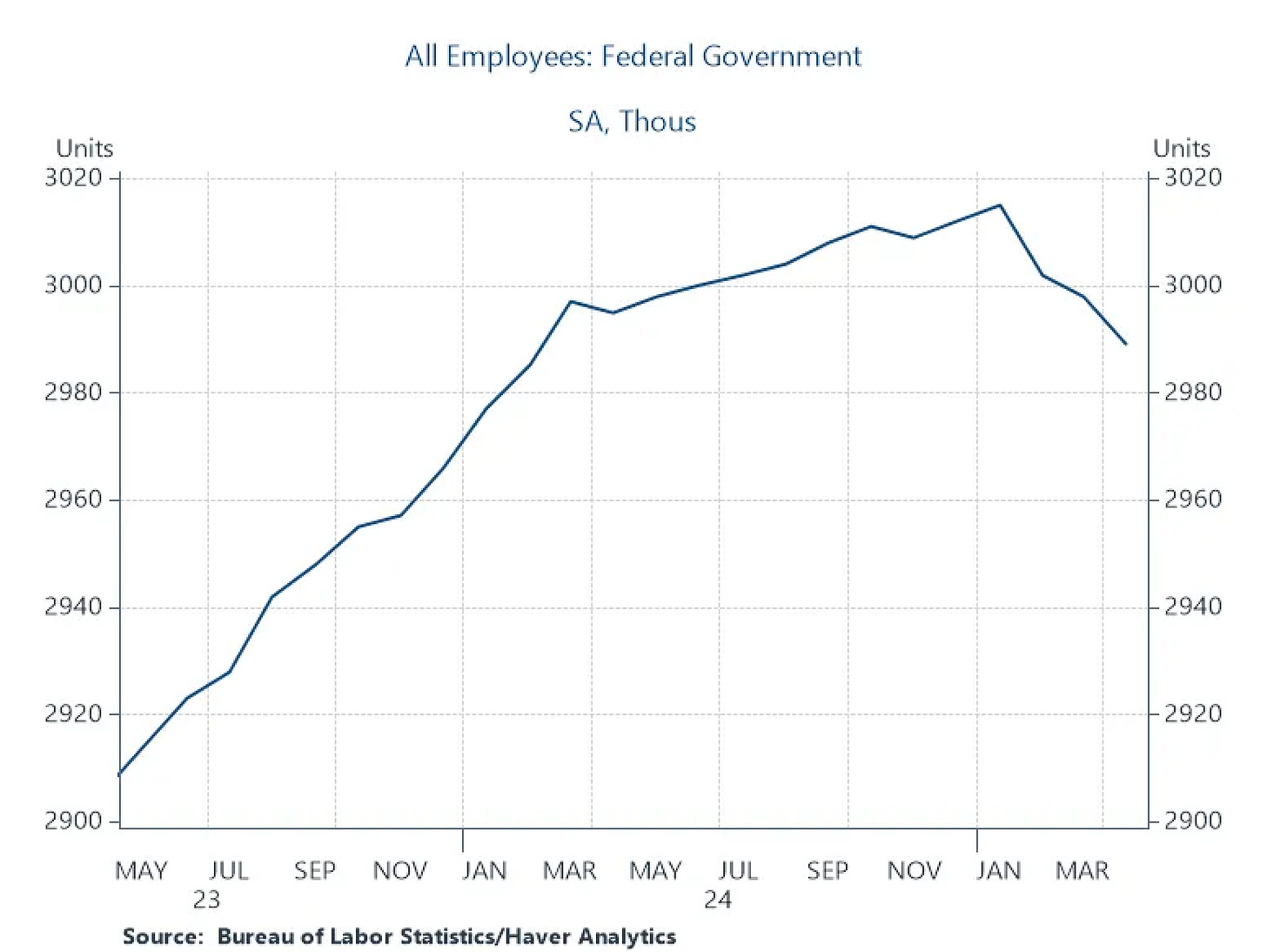

And the federal job cuts made by the Trump Administration’s DOGE team have continued to pile up, with 26,000 federal jobs lost since Trump took office. Many other federal workers are currently in limbo, with judges’ court orders keeping laid-off workers employed until their arguments can move through the court system.

Bernstein concludes that consumer demand and spending are still strong, and the job creation numbers are still on the positive side of the ledger, which means there’s still a chance that we can avoid spiking unemployment numbers if the tariffs are stopped.

The Burning Glass Institute’s Director of Economic Research, Guy Berger, points out that for roughly two years our labor market has been in an interesting state of equilibrium: Workers aren’t being laid off en masse, but hiring hasn’t exactly been through the roof, either. While that results in strong unemployment reports like we saw last month, it also means that young workers aren’t finding employment.

“High school grads in their late teens have averaged an unemployment of 14.5% over the last 12 months, an increase of 2.5 percentage points relative to early 2023,” Berger writes.

And recent college graduates are doing better than their high school graduate counterparts, but it’s still harder for them to find work: Berger says that college grads in their early twenties are averaging “an unemployment rate of 6.6%, an increase of 1.2 percentage points relative to mid-2023.”

As we saw during the Great Recession, when young workers leaving school have a hard time entering the job market, that isn’t just a temporary inconvenience—it creates a serious gap in their lifelong earning potential. Students who entered the job market during the Great Recession, for example, were found to “earn approximately 17.5 percent less per year than comparable peers graduating in better labor markets,” reports Brookings. “This lower wage effect is highly persistent, fading away only after 17 years of work.”

Obviously, today’s recent graduates aren’t in that kind of economic danger yet. But the job market is heading in the wrong direction. Tomorrow’s American workforce needs more hiring opportunities, not fewer.

Tariffs Set the Stage for a New Wave of Corporate Greedflation

Matt Stoller spotlighted an important report from the St. Louis Fed that put a price tag on the greedflation that we saw during the pandemic, in which big corporations took advantage of inflation expectations by raising prices much higher than costs and pocketing that extra revenue in the form of record profits.

Specifically, from the beginning of the pandemic, “domestic non-financial corporate profits doubled, to $4 trillion a year. As a percentage of total economic output going to profits, they went from 13.9% to 16.2%, while the labor share modestly declined,” Stoller explains.

Additionally, those doubled profits weren’t invested back into the companies to improve customer experiences or raise worker pay. Instead, they were simply airlifted away to an elite class of shareholders in the form of stock buybacks. And as the below graph from the report shows, these runaway profits from price-gouging were a uniquely American phenomenon:

As you can see on the green line at the bottom of the graph, the rest of the world’s corporate profits as a share of national income actually declined a little bit from the beginning of the pandemic, while American corporations soared and stayed aloft to the present day. (And interestingly American financial industries have stayed level throughout the pandemic, which is perhaps a testament to the banking regulatory structure leaders put in place after the Great Recession.)

Stoller then builds on the lessons from this report to warn that corporations are likely to use the expectations of higher prices from our current tariff crisis to yet again jack up prices far above costs and take their profit margins even higher.

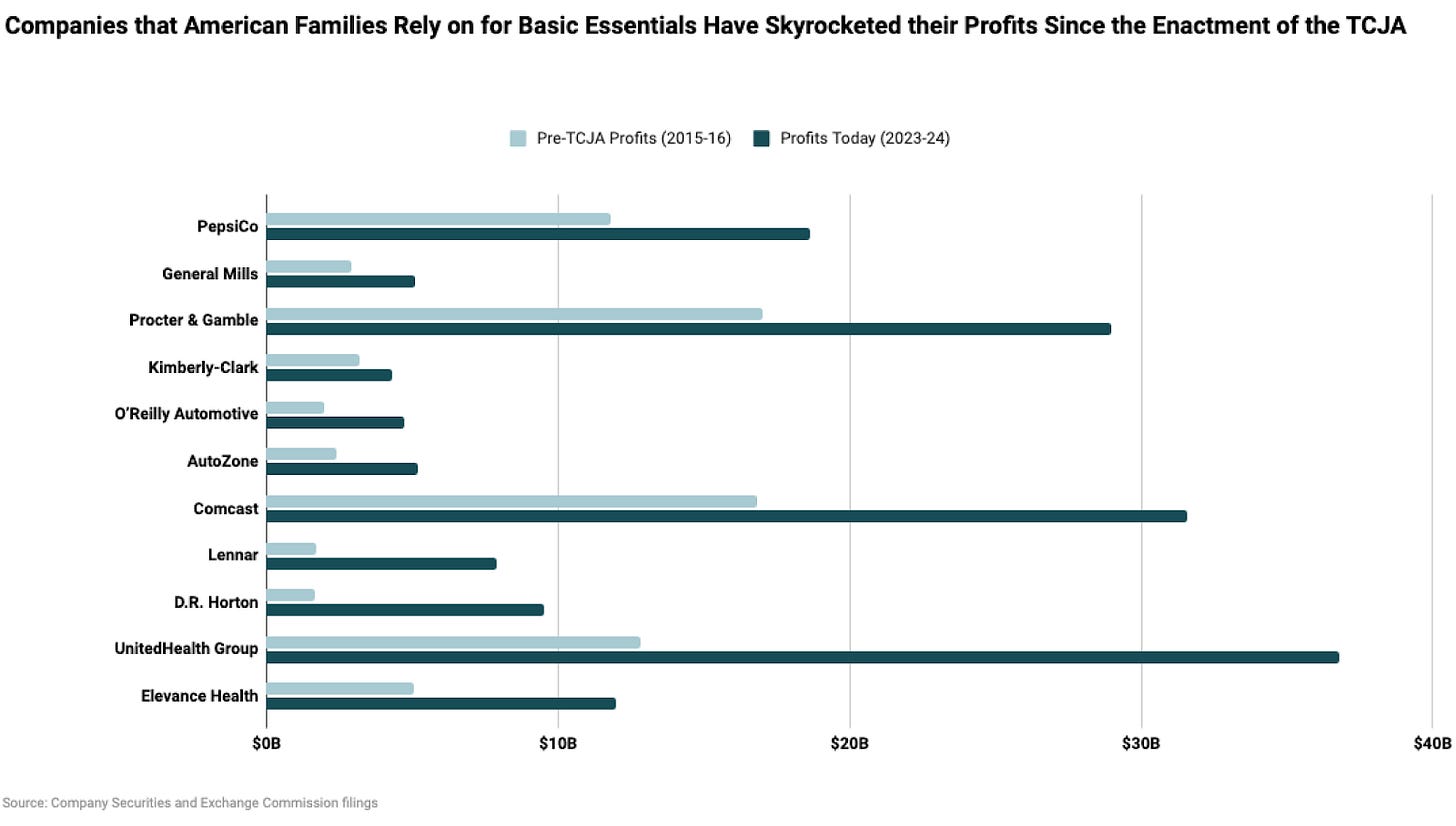

And a new report from Groundwork Collaborative looks at the prices and profit margins of 11 major corporations that benefitted from President Trump’s 2017 tax plan, which dramatically slashed the corporate tax rate. Groundwork found that those 11 corporations alone have “raked in nearly $500 billion in profits and enriched their shareholders by $463 billion while paying just $140 billion in federal income taxes.” Many of these corporations then went on to gouge prices during the pandemic, enlarging their profit margins even higher.

When Trump and House Republicans unveiled their tax plan in 2017, they promised that most American households would make between $4000 and 9000 extra every year. That money never materialized. And thanks to pandemic-era inflation and its attendant greedflation, consumers wound up paying 30% more for groceries in the years after the pandemic, while profits for grocery companies like General Mills soared by 75%.

Greedflation wasn’t a one-time aberration during the pandemic—in fact, the Groundwork report proved that greedflation isn’t really over, and that corporate profits are still climbing higher even today. American corporations are uniquely skilled at ripping off consumers in times of crisis and then handing those ever-increasing profits off to shareholders with no strings attached.

The good news is that we know how to solve this problem. We have to break up monopolies, lock down on stock buybacks with higher taxes, and establish stricter regulations ensuring that workers get a share of the same profits that shareholders do. Once we stop a tiny class of elite shareholders from looting exorbitant profits for personal gain, price-gouging and greedflation will stop erupting every time the market faces any kind of disruption.

This Week in Trickle-Down

“Defense spending, border security and health care for veterans are the biggest winners in President Trump's budget proposal — while programs to support housing, health and climate stand to take massive cuts,” writes Axios’s Ben Berkowitz. “The fiscal blueprint cuts discretionary non-defense spending by $163 billion — a 22.6% cut.”

Meanwhile, Congressional Republicans’ proposed cuts to Medicare would result in the widespread closure of rural hospitals, warns the Center for American Progress, which notes that “190 rural inpatient hospitals are already at risk of immediate closure in 34 of the states that have expanded Medicaid.”.

“Medicaid is the only way to access affordable sexual and reproductive healthcare for many low-income women and young people—it pays for a range of reproductive health services, including birth control and family planning, annual wellness exams, breast and cervical cancer screenings, prenatal and postpartum care, and STI screenings and treatment for conditions like HIV,” writes Kierra Jones at Ms. “If Medicaid funding is slashed, these essential services would become far less accessible. Millions of Americans could lose their coverage entirely, leading many American women and young people to worry if they will face higher out-of-pocket costs for basic care.”

This Week in Middle-Out

For those trickle-downers who believe that taxes shrink wealth, a new study proves that raising taxes is actually good for everyone, including the wealthiest few: “Two years into Massachusetts’ millionaires’ tax and a higher tax rate on $250,000 in capital gains in Washington state shows that the millionaire class grew by 38.6 percent in Massachusetts and 46.9 percent in Washington, respectively,” reports the Institute for Policy Studies. “Their wealth grew by more than $580 billion in current dollars in Massachusetts and $748 billion in Washington state between 2022 and 2024.”

IPS also reports that “In New York and Rhode Island, the total wealth of those with at least $1 million in assets grew as well. From 2010 to 2024, these four states saw a total wealth increase of about 200 percent, from $3.7 trillion to $11.2 trillion.”

A judge ruled that Apple abused its monopoly power as the proprietor of the App Store and ruled that the company “is no longer allowed to collect fees on purchases made outside apps and blocks the company from restricting how developers can point users to where they can make purchases outside of apps.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Legal scholar and former Biden advisor K. Sabeel Rahman joins Nick and Goldy for a thoughtful and surprising conversation about his theory that American democracy needs a 21st-century upgrade. When wealthy people and corporations can simply ignore the law, Rahman suggests, then the rule of law is meaningless. He makes a pitch for a conversation to plan a new democratic “operating system” for the United States which truly puts the power in the hands of the people.

Closing Thoughts

Ocean travel is economical, but it’s very, very slow. This week, the first wave of container ships from China to be subject to tariffs levied by President Donald Trump on April 2nd have finally begun pulling into U.S. ports. So we’re really just beginning to see the impact of what those tariffs will cost American consumers—and many experts believe that we won’t fully understand their impact until midsummer at the earliest.

But we’re starting to get an early wave of data that’s dimensionalizing the hit that consumers will be taking in this trade war. Americans for Tax Fairness released a report tallying the price tag of Donald Trump’s first month of tariffs.

They conclude that in April alone, “taxes on foreign imports spiked to $96.3 billion just in the first quarter of 2025, up $14 billion, or 17%, from the same period in 2024.”

“Trump’s tariff agenda (even with its recent pauses and backdowns) translates into an 18% effective tax rate on all imported goods by the end of 2025,” Americans for Tax Fairness concludes. This tax rate on consumers is “the highest since 1934, when America was in the throes of the Great Depression.”

The tariff rate is now higher than America’s corporate tax rate:

Unlike the corporate tax rate, which is paid by wealthy corporations, the tariffs are ultimately paid by American consumers when they buy products. And as middle-out economics teaches us, working Americans buy more products than the wealthy few ever could, which means that poorer Americans are paying a bigger share of tariffs than the wealthiest one percent.

Americans for Tax Fairness concludes that “while the bottom 60% of households take home roughly one-fifth of national income, they will pay nearly one-third the price of Trump’s tariff regime.”

“Meanwhile, the top 1% highest-income households—those that take in over $940,000 a year— will pay only one-tenth of the Trump Tariff Tax, even though they get well over one-fifth of national income,” they note.

It’s important to share that final point far and wide: Tariffs are actually exacerbating economic inequality because they punish working Americans more than the wealthy few.

And lastly, though we spend a lot of time in this newsletter talking about the negative effects of trickle-down policies that enrich the wealthy few at the expense of everyone else, it’s important to note that technically this tariff regime isn’t even technically trickle-down economics—it’s a callback to the mercantilism that existed in the 1800s, before trickle-down economics was even invented.

It will be interesting to see if, in the days ahead, trickle-downers realize that their economic system, that took hold over both parties for most of the last 40 years, is under assault from the Trump Administration. I’m curious to see how trickle-down institutions might respond if they realize that their dominance in the Republican Party is at risk of being replaced.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach