Friends,

“Dollar General reported better-than-expected Q1 earnings yesterday and raised full-year estimates—not in spite of tariff price hikes, but because of them,” writes Matty Merritt at Morning Brew.

Dollar General is uniquely positioned to measure the economic health of poor Americans because nearly two-thirds of its customers live in households that earn less than $30,000 annually. Last quarter, the retailer’s sales were 5% higher, and Merritt reports that “the average amount spent per transaction went up 2.7%.”

At the same time, customer traffic dropped by a third of a percentage point. This was a common trend we saw during the greedflation-inspired price spikes of 2022—fewer customers spending more per transaction—and while Dollar General reported these statistics as good news in its quarterly report, most of their customers probably experienced it as economic pain.

Another corporation’s annual reports offered more insight into the economic lives of working Americans. Soup and snack manufacturer Campbell’s Co. saw overall sales rise in the last quarter, even as sales of several of their snack foods like crackers and chips dipped by 4%.

Dee-Ann Durbin at the Associated Press explains, “Campbell’s saw the highest level of meals cooked at home since early 2020 in its fiscal third quarter, which ended April 27. Campbell’s noted sales of its broths rose 15% during the quarter while sales of its Rao’s pasta sauces were up 2%.”

Other figures back up Campbell’s assertion. Durbin noted in early May that McDonald’s store traffic dropped by 3.6% in the first quarter. “That was the biggest U.S. decline McDonald’s has seen since 2020, when a pandemic shuttered stores and restaurants and other public spaces nationwide,” Durbin notes.

McDonald’s claimed that it was not unique in this decline in foot traffic. Across the fast-food industry, “traffic from consumers making $45,000 per year or less was down by double-digit percentages,” Durbin reports, adding that “traffic from middle-income consumers was down nearly as much. Only traffic from those making $100,000 or more remained solid.”

The claims from Campbell’s and McDonald’s are mirrored by the most recent report from the US Inflation Calculator, which shows that from April 2024 to April 2025, the price of making food at home rose by 2%, while the price of food away from home rose by nearly double that, at 3.9%. During that same period, real worker wages only grew by 1.4%.

Putting all these figures together, it looks as though low-income families are cutting consumption and trying to find ways to stretch their dollars as far as possible, and middle-class families aren’t too far behind.

Self-reporting economic information from Navigator research seems to back this up: Thanks to “perceived lack of stability and increased costs, nearly half of Americans say they are not going out to restaurants, movies, and other recreational activities (47 percent), are saving less than they would like (46 percent), and are cutting back on purchasing daily goods like groceries (42 percent),” Navigator said.

Because they’ve been primed by 40 years of trickle-down propaganda to measure the health of the economy through corporate profits and the wealth of the 1%, our media and economic models aren’t prepared to catch slowdowns at the bottom of the wage scale like this. But if the slowdown in spending continues and is worsened by high prices caused by tariffs, it could result in job losses and an accelerating negative feedback loop of decreased consumer demand.

Americans at the lower end of the income scale are the essential workers who kept the American economy going throughout the lockdown days of Covid, and they’re the consumers whose spending power helped our economy come roaring back from the supply chain shocks that rocked the world in 2022. If these warning signals are correct and they are in trouble now, the whole economy will be in trouble.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The Not-So-Great Stay

“The number of Americans filing new applications for jobless benefits increased more than expected last week and the unemployment rate appeared to have picked up in May,” reports Lucia Mutikani at Reuters, who adds that the surprising rise in jobless benefit applications suggests that “layoffs were rising as tariffs cloud the economic outlook.”

“Initial claims for state unemployment benefits rose 14,000 to a seasonally adjusted 240,000 for the week ended May 24,” Mutikani writes, adding that there is some sign that President Trump’s program of tariffs are starting to affect workers: “Unadjusted claims for Michigan jumped 3,329. The automobile industry has been hit with a 25% duty on parts,” she writes. (And those auto manufacturing jobs were lost before this week’s 50% tariffs on steel and aluminum were established by the Trump Administration.)

“A report from the Bank of America Institute noted a sharp rise in higher-income households receiving unemployment benefits between February and April compared to the same period last year,” Mutikani writes, adding the report “also showed notable rises among lower-income as well as middle-income households in April from the same period a year ago.”

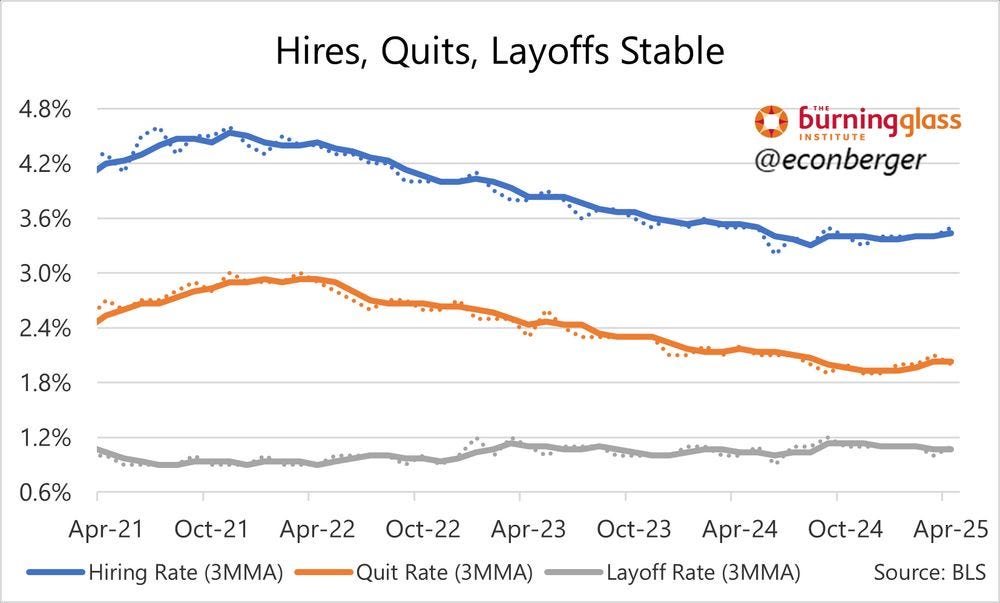

But none of that bad news showed up in this month’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) report from the Department of Labor. In fact, job openings unexpectedly increased a bit, improving the outlook for job-seekers. But on the whole, things stayed mostly the same. Economist Guy Berger reports that hires and quits have remained stable for the month, and layoffs continue to be historically low and surprisingly stable.

Unlike the “Great Resignation” we saw during 2022 and 2023, when workers were leaving jobs in high numbers and taking similar positions for much higher wages, we’re now not seeing workers quitting or being fired in large numbers. Berger characterizes this moment as “The Great Stay.”

Economist Aaron Sojourner agrees, writing “1.79 American employees quit their job in April for each employee fired by their boss (layoffs+discharges), down from 2.10 in March due to both declining quits & rise in firings.” He explains that this quit-fire relationship is the Labor Leverage Ratio, “a proxy for employee bargaining power.”

Workers, sensing uncertainty in the economy and a difficult labor market for hiring, are staying put. The job market “is frozen in place. Huge uncertainty makes doing nothing appealing. No hiring. No firing,” Sojourner writes.

Sojourner adds that all this stillness in the job market means worker bargaining power “fell to pre-pandemic levels, reversing recent increases” in the paychecks of workers.

It remains to be seen if the signs of “cracks” in the labor market reported by Mutikani in Reuters this week will show up in tomorrow’s monthly unemployment report from the Department of Labor, or if May’s jobs report will reflect the stasis of the monthly JOLTS numbers. At the moment, it looks like the most positive measurements show the labor market treading water.

Americans Aren’t Building Right Now

Bill McBride reports that construction spending for the month of April declined by .4%, below economists’ expectations. Worse, this month’s construction report showed that American construction “spending for the previous two months were revised down significantly.”

The biggest dip in construction spending, unfortunately, comes in private residence construction. We’re now spending a whopping 8.9% less on the construction of private residences than we were in 2022, when spending was at its peak:

“On a year-over-year basis, private residential construction spending is down 4.8%,” McBride writes. This is potentially bad news for housing prices. If new houses don’t become available at anything near the rate of housing demand, it’s hard to envision an end to the housing crisis that has now reached nearly every state in the union.

Meanwhile, American manufacturing contracted for the third consecutive month in May, according to the ISM manufacturing index. The decrease in new export orders—meaning other countries ordering products manufactured in the US—”continues to be the fastest since the coronavirus pandemic, and excluding COVID-19, the reading is the lowest since the Great Recession (39.4 percent in March 2009),” according to ISM.

The toplines on the ISM report are almost entirely bad news, with contractions in new orders and backlogs, manufacturing employment contracting, deliveries slowing, raw material inventories contracting, and prices increasing. Obviously, this rapid decline is a direct result of the campaign of tariffs enacted by President Trump.

Respondents to the ISM survey are very plain about the causes of their higher prices and contracting manufacturing numbers: “Most suppliers are passing through tariffs at full value to us,” a chemical product manufacturer reported. “The position being communicated is that the supplier considers it a tax, and taxes always get passed through to the customer. Very few are absorbing any portion of the tariffs.”

An appliance and appliance part manufacturer wasted no words: ““The administration’s tariffs alone have created supply chain disruptions rivaling that of COVID-19.” As we’ll see in the next section, these manufacturers aren’t the only ones who are unhappy with the tariffs.

Working Americans Dislike Tariffs

Earlier in this newsletter, I mentioned a Navigator polling report showing that nearly half of all Americans are cutting back on purchases due to economic uncertainty caused by the tariffs.

The whole Navigator report is worth your time. Here’s the topline: “A majority of Americans (56 percent), including 61 percent of independents, disapprove of President Trump’s handling of the economy. Majorities describe the economy as ‘volatile’ (67 percent) and ‘uncertain’ (67 percent) rather than ‘stable’ (28 percent).”

This poll is interesting because it helps establish that while inflation headlines have mostly vanished from newspapers, high prices still dominate our lives. Two-thirds of Americans, including roughly half of all Republican respondents, told Navigator that their costs are going up.

Americans broadly agree on tariffs. Only one-third of Americans believe that tariffs are good for the economy, and two-thirds of Americans believe that tariffs are raising costs.

And here is perhaps the most fascinating discovery in the whole poll: Navigator asked Americans if they believed that the economic pressure caused by tariffs would eventually be worth it in the long run—that is, if they believed that tariffs would bring manufacturing back to the United States and grow a stronger economy.

“By an 11-point margin, Americans say that the economic pain caused by tariffs will not be worth it in the long run (38 percent worth it- 49 percent not), driven by 70 percent of Republicans who believe tariffs will be worth it,” Navigator reports.

But it wasn’t the partisan divide that surprised me. Rather, it was the class divide. Check out the detail from this graph showing belief that tariffs will be worth it in the long run, divided into household wealth. The blue line denotes the number of people who believe tariffs will eventually improve the economy. The red line represents those who believe tariffs will harm the economy. Purple means “I don’t anticipate any economic pain” and grey means “I don’t know.”

The only majority pro-tariff group are households that earn more than $100,000 per year. Tariffs only seem to appeal to the Americans who are most likely to be able to absorb the additional thousands of dollars per year that tariffs are projected to cost working families.

This Week in Trickle-Down

“The Trump administration on Friday unveiled fuller details of its proposal to slash about $163 billion in federal spending next fiscal year, offering a more intricate glimpse into the vast array of education, health, housing and labor programs that would be hit by the deepest cuts,” reports Tony Romm at the New York Times.

The Economic Policy Institute warns that the Trump tax cuts as passed by House Republicans would kick 15 million Americans off of health insurance.

This Week in Middle-Out

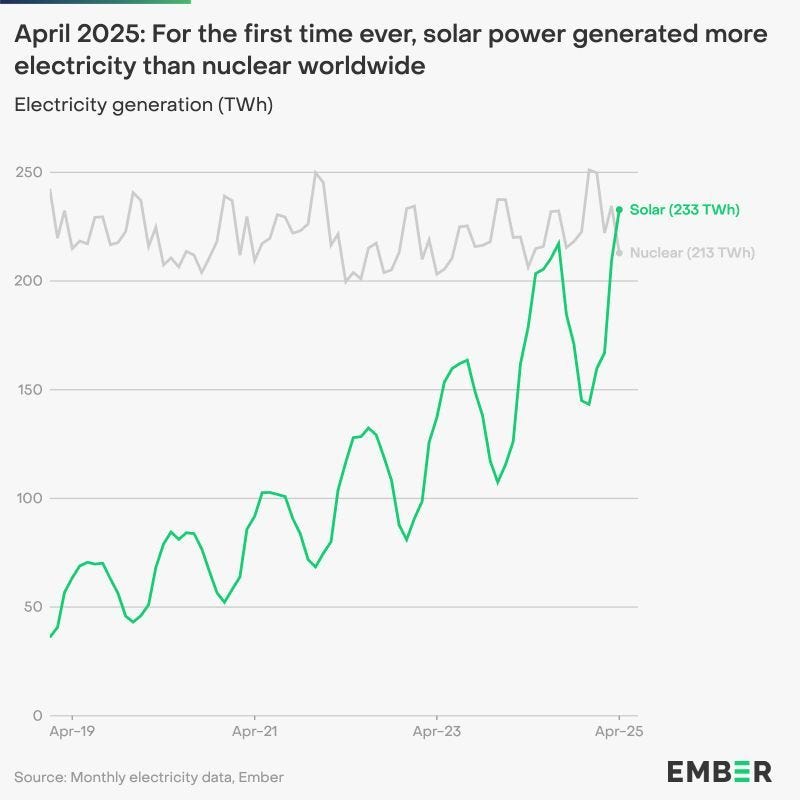

“For the first time, solar power generated more electricity globally than nuclear, making it the world’s 4th largest power source,” reports Jan Rosenow on Bluesky.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Lily Roberts, the managing director for Inclusive Growth at the Center for American Progress, joins Goldy and Paul this week to explain why the Republican budget cuts to SNAP programs aren’t just a disaster for Americans suffering with poverty and economic instability. SNAP also supports tens of thousands of retailers and farmers around the country, making it a small business support program. Because SNAP spends like money, cuts to SNAP will result in massive losses to communities around the nation—especially in the poorest parts of the country.

Closing Thoughts

“The typical compensation package for chief executives who run companies in the S&P 500 jumped nearly 10% in 2024 as the stock market enjoyed another banner year and corporate profits rose sharply,” reports Mae Anderson and Paul Harloff at the Associated Press.

“The median pay package for CEOs rose to $17.1,” the AP explains.

Several of the experts that the Associated Press consulted for comment on the story argued that because 2024 was a record-breaking year in terms of corporate profits, the nearly 10% raise in CEO pay was simply a reflection of the work that they put in to raise those profits.

But the workers who created the value reflected in those profits apparently don’t get the same share. The AP notes that “the median employee at companies in the survey earned $85,419, reflecting a 1.7% increase year over year.”

Trickle-downers love to promote the myth that workers’ paychecks accurately reflect their value. But it’s hard to imagine that any CEO is actually worth more than 1000 times the value of their workers. That’s how it is at several of these corporations: “at cruise line company Carnival Corp., its CEO earned nearly 1,300 times the median pay of $16,900 for its workers. McDonald’s CEO makes about 1,000 times what a worker making the company’s median pay does,” AP reports.

Few CEOs earn anything close to what their workers make. In fact, at “half the companies in AP’s annual pay survey, it would take the worker at the middle of the company’s pay scale 192 years to make what the CEO did in one.”

We are starting to see some pushback against outrageous CEO compensation. Elon Musk was sued by shareholders after Tesla’s board tried to give him a $56 billion pay package. And this week, 60% of Warner Brothers Discovery shareholders voted against executive compensation including a $50 million compensation package for Warner CEO David Zaslav.

Outsized wealth inequality always brings out intense feelings. As Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer warned in his open letter to fellow wealthy plutocrats, “If we don’t do something to fix the glaring inequities in this economy, the pitchforks are going to come for us.”

Of course, if CEOs kept their pay at a more human scale—say a multiple of ten times their median employee—and actually paid their taxes, they could probably eliminate those security packages altogether. Americans love to celebrate our successes, and until recently CEOs and business leaders were counted among those heroes. But the mood is turning sharply.

But if there’s one thing Americans hate, it’s someone who thinks they’re above everyone else—and with these eight-figure annual payouts, CEOs are sending a message about how little they value American workers.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach