Friends,

As Senator Robert F. Kennedy famously argued in 1968, the Gross Domestic Product is not a perfect measurement of the American economy. It doesn’t measure how vibrant our communities are, how long and healthy our lives are, or the quality of our work/life balance. The metrics that the quarterly GDP report does analyze—specifically, all the goods and services produced and consumed in the United States—are specifically designed to gauge the economic health of corporate America and the wealthy few, meaning that it was created to affirm and prioritize the trickle-down economic worldview that falsely believes wealthy Americans are the creators of economic growth and widespread prosperity.

One of the most important long-term projects for middle-out economics is to devise a new way to measure the American economy that instead prioritizes the economic health of working Americans, who are the true creators of wealth. By measuring how CEOs, Wall Street hedge fund guys, and the super-rich are doing, the GDP tends to miss some of the most important metrics of our economic health.

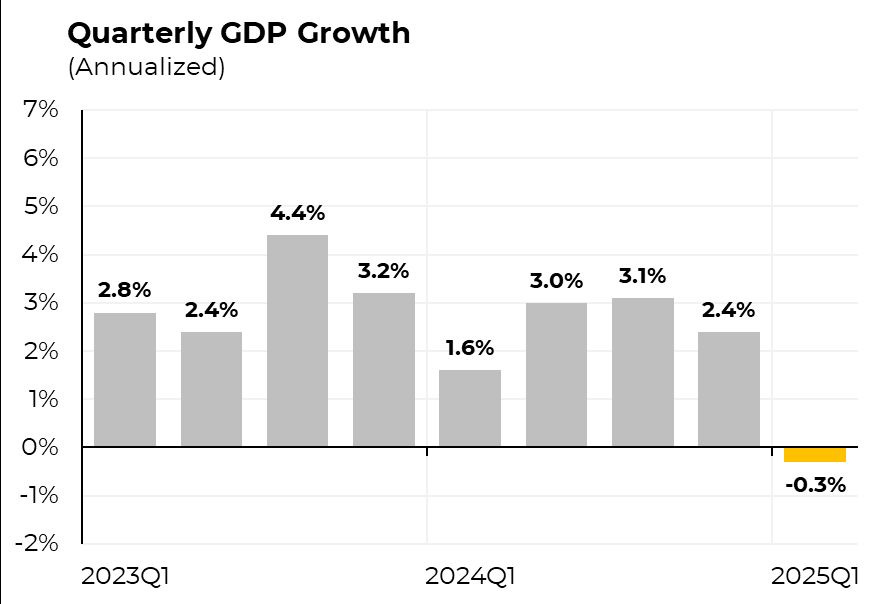

But even with all that said, yesterday’s GDP report was quite remarkable. It showed the economy contracting by 0.3%—the first such contraction since 2022, when pandemic-era global supply shocks rocked the economy.

Many of the underlying economic factors of the first-quarter GDP report continued the strong trend we’d been seeing for the last two years. Economist Joey Politano notes that private consumption and fixed investment, meaning how consumers were spending and how businesses were preparing for the future, were nearly as strong as in recent GDP reports.

So what changed? Two things: Trade and government spending. First, because it only measures goods and services created in the United States, the GDP was depressed by remarkably high import numbers. That’s the result of corporations ordering as many products from abroad as possible before Trump’s tariffs were put into effect. (Remember, this GDP report covers January through March, ending before Trump’s so-called “Liberation Day” on April 2nd and the tariff chaos that followed.) Without that massive wave of imports, the GDP would have almost certainly been on the positive side of the ledger.

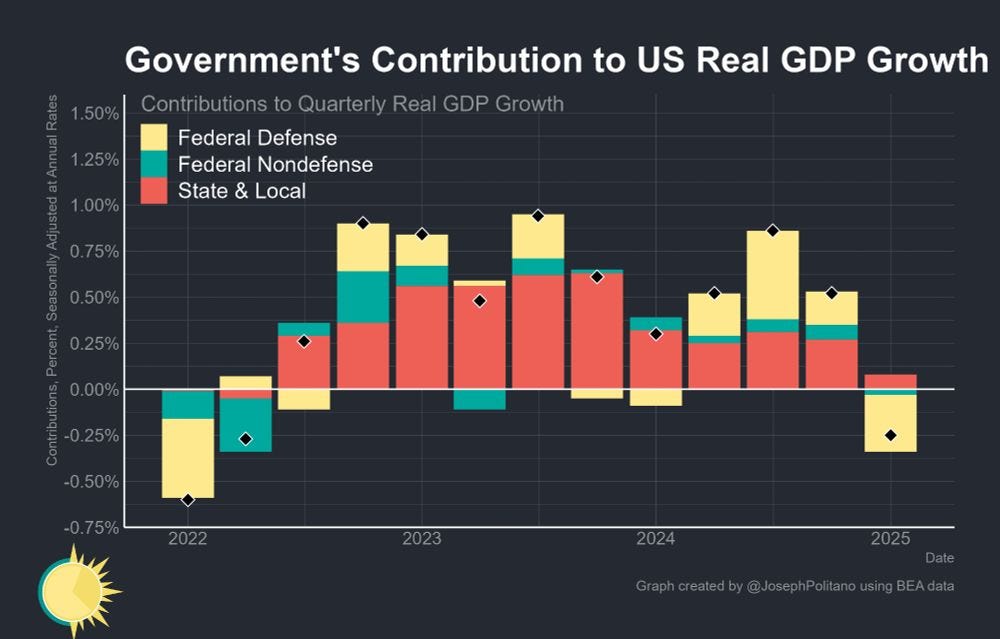

And secondly, as Politano notes, “there was a large reversal in government's contribution to GDP growth, which sank to the lowest levels since early 2022, mostly led by a fall in federal defense spending.”

The most fascinating thing about this economic contraction is that, unlike any other GDP report I can think of, it is entirely the result of one man’s decisions—had President Trump changed nothing about tariffs or kept government spending flat, the GDP would likely have come in at roughly the same level as past reports.

“While the first quarter figures showed basically solid growth beneath the tariff-induced noise,” reports Ben Casselman at the New York Times, “forecasters widely expect spending and investment to slow in the months ahead, as tariffs drive up prices and uncertainty keeps businesses on hold.”

In his nuanced look at the GDP report, former Biden economist Jared Bernstein concludes, “the message from this report is very much akin to the sign in the woods in a horror movie: Turn Back Before It’s Too Late!”

So the GDP report shows that the corner offices of America are skittish and skeptical about the Trump Administration’s economic policies. On this International Workers’ Day, when workers around the world celebrate their victories, we should ask: How are American workers doing? We got some bad news on that front yesterday, in the form of the Upjohn Institute’s New Hires Quality Index (PDF), which measures the earnings of newly employed Americans between February and March. The Upjohn Institute found that even though “inflation-adjusted hourly earnings power of individuals starting a new job notched a gain of 0.2 percent between February and March of 2025, to $21.99, breaking a two-month losing streak,” new hire wages are “still down 0.6 percent from one year ago, and down 1.3 percent from its peak in July 2023”

Upjohn Institute further warns that their indicators show “the odds of a recession appear to be rising, even if we do not appear to be in one. Yet. Although many people associate recessions with increasing layoffs, job losses tend to occur during the later stages of a recession,” they explain. In reality, “The early warning signs come more from reductions in hiring, which we’ve now seen for nearly two years without a recession.”

I’ve thrown a lot of numbers at you, so let’s just round up by returning to our most important economic rule of thumb: while the GDP report garners more headlines, I urge you to keep your eyes on unemployment numbers and wage growth as the most important sign of our nation’s economic health. Working Americans, not CEOs, create jobs in our economy, and their prosperity is what matters most for all of us.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

Tariff Uncertainty Continues

“Donald Trump’s trade war with Beijing is starting to affect the wider US economy as container port operators and air freight managers report sharp declines in goods transported from China,” reports the Financial Times.

Remember, container ships move very slowly. And so we’re just starting to see the effects of Trump’s tariffs on the flow of container ship traffic. The Financial Times notes that “the first container shipments from China to face tariffs are due to land in the US in the coming week.”

We can already see what those tariffs are doing to tariff shipments in the future: The FT adds that “Logistics groups said container bookings to the US have fallen sharply since the introduction of 145 per cent tariffs on Chinese imports to the US.”

Just as the supply chain disruptions caused by turning the global economy off and then back on again during the pandemic were felt for months and years afterward, this self-inflicted supply chain disruption will be felt in America for months to come.

This delayed response means that even if Trump were to completely retract his tariffs tomorrow, there would be at least one monthlong gap in the supply chain. That lack of imports affects everyone: The unionized dockworkers who empty the container ships, the truckers who drive those goods across the country, and the retail workers who stock the shelves and ring up customers.

David Dayen at the American Prospect makes an educated guess about when consumers will really start to feel the impact of the tariffs in their day-to-day-lives: “people will see these effects on store shelves around midsummer, precisely when economists at Apollo Global Management (I’m no lover of private equity, but hey, they know money) place the start of the recession,” he writes.

For an idea of what these tariff-inspired supply chain disruptions might look like to American employers, the Dallas Federal Reserve’s April manufacturer survey offers a bleak outlook. The report opens with some good news: Factory activity slightly rose in Texas last month. But from there, things take a downward turn. Specifically, the Fed reports that the new orders index, which tallies up orders taken by Texas manufacturers over the course of the month, “plummeted 20 points to -20.0.” At the same time, “The raw materials prices index jumped 11 points to 48.4, its highest reading since mid-2022.”

“Perceptions of broader business conditions continued to worsen notably in April,” the Fed continues. “The general business activity index fell 20 points to -35.8, its lowest reading since May 2020. The company outlook index also retreated to a postpandemic low of -28.3. The outlook uncertainty index pushed up 11 points to 47.1.”

The interviews with Texas manufacturers in the report are also illuminating. “There is really no way to predict anything accurately six months out or even six weeks out now for our industry due to the tariff and trade uncertainty,” one manufacturer told the Fed. “Carve-outs for large electronics businesses (cellphones and laptops) leaves small business burdened to deal with tariffs on our own, which are likely to cause delays, cancellations and early product obsolescence on existing products and orders.”

These complaints are spreading across every type of manufacturing surveyed by the Dallas Fed:

Food manufacturers: “Tariffs and tariff uncertainty are wreaking havoc on our supply lines and capital spending plans.”

Machinery manufacturers: “Due to tariffs, we do not know what to expect.”

Paper Manufacturers: “We have seen continued slow order entry now for four months.”

Printers: “The tariff issue is a mess, and we are now starting to see vendors passing along increases, which we will have to in turn pass along to our customers. Because of this, we are very concerned about general business activity for the next six to nine months or until these trade agreements get worked out.”

Textile manufacturers: “Sales are down, and uncertainty is very high. We import raw materials and finished goods and are very nervous about tariff impacts (especially China). We will likely need to increase prices, which will likely hurt demand/sales. We are expecting to get hit on both the supply and demand side. There is a lot of uncertainty.”

Between the data showing fewer ships on the way and anecdotal evidence of manufacturers saying their costs are increasing and consumer demand is decreasing, we now are getting a pretty clear picture of the impact that heightened tariffs are having on the economy. It seems like a given that real economic pain is on the way for Americans. The big question is how long that pain will last.

America’s 19 Richest Families Own Almost 2% of America’s Wealth

“New data suggest $1 trillion of wealth was created for the 19 richest American households alone in 2024. That is more than the value of Switzerland’s entire economy,” reports Juliet Chung for the Wall Street Journal.

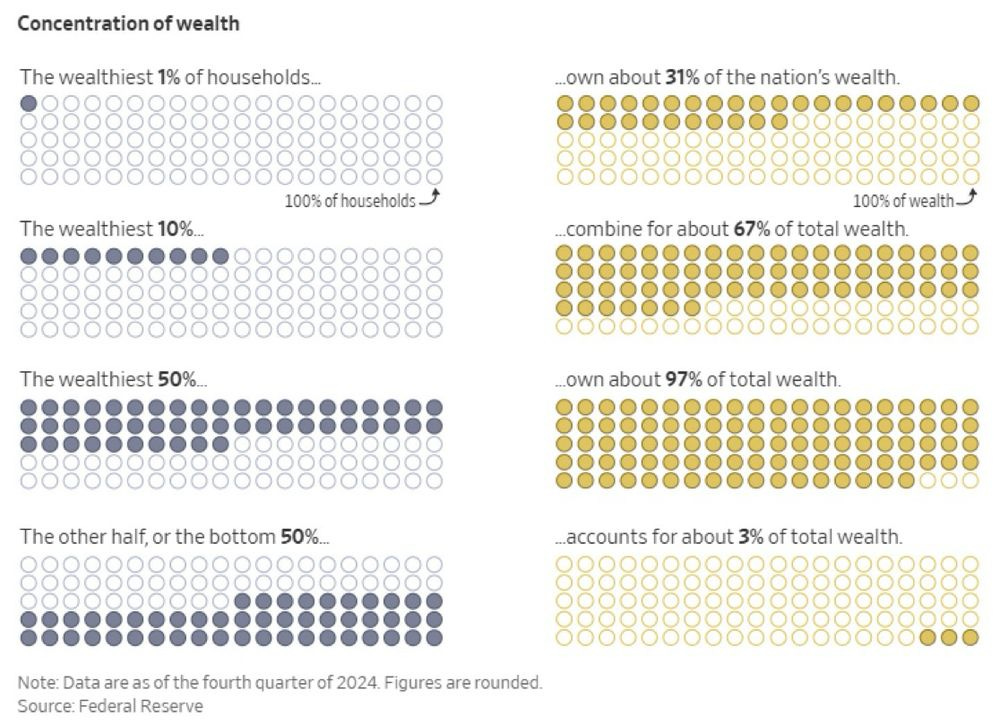

Those 19 wealthiest families, the top 0.00001% of the economy, now own 1.8% of total American household wealth. And the 1.2 million households in the wealthiest one percent of the economy now own nearly a full third of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom 50% of American households only own about 3% of the nation’s wealth.

This is a direct result of trickle-down economics—it’s what happens when lawmakers prioritize investing in the wealthy few at the expense of broadly investing in American workers. One Bluesky user pointed out that the growth of the 19 wealthiest families was caused by trickle-down economics by adding one line to a graphic from the Wall Street Journal story:

It’s important to point out the correlation between Reagan’s presidency and the rise of wealth inequality not to blame one person for all our economic woes—in fact, trickle-down economics has had an army of thousands of elected leaders from both parties helping it grow through the years—but rather to point out that trickle-down is a choice. It’s the result of policies that were put in place to achieve a desired result. Just as that wealth was transferred to the super-rich on purpose, we can also choose to invest it in working Americans. That’s the happy work we write about in this newsletter every week.

The Federal Minimum Wage Is Now Officially a Poverty Wage

“In 2025, the federal minimum wage is officially a ‘poverty wage,’” reports Sebastian Martinez Hickey and Ismael Cid-Martinez at the Economic Policy Institute. “The annual earnings of a single adult working full-time, year-round at $7.25 an hour now fall below the poverty threshold of $15,650 (established by the Department of Health and Human Services guidelines).”

It’s true that many states and cities have raised their minimum wage far higher than the federal minimum of $7.25 an hour. But many states still adhere to the federal minimum, and this interactive Oxfam map shows that states that have low minimum wages tend to have more impoverished and low-wage workers.

Keeping the minimum wage artificially low doesn’t just affect the few hundred thousand workers actually earning the minimum wage—it suppresses wages across the bottom twp-thirds of the wage scale.

“Overall, 58.3 million [U.S.] workers (43.7 percent) earn under $15 an hour;” Oxfam reports, noting that “41.7 million (31.3 percent) earn under $12 an hour.” Many of those poorest workers live in states that keep to the federal minimum wage.

“Research shows that increasing the minimum wage decreases poverty by increasing the incomes of low-income families, even accounting for decreases in public benefits as families earn more from higher wages,” EPI reports. “In analysis of legislation introduced in 2021 to gradually increase the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, EPI concluded that the policy would lift between 1.8 to 3.7 million individuals out of poverty, including up to 1.3 million children.”

Since its creation nearly ninety years ago, the federal minimum wage has never gone this long without an increase, and its value in real dollars is lower than it’s been in seventy-five years. Trickle-downers have never been closer to achieving their dream of eliminating the minimum wage altogether, and that’s a fact that should alarm all working Americans.

This Week in Trickle-Down

“The United Parcel Service (UPS) is expected to cut about 20,000 jobs in 2025 as a part of a larger plan to reduce costs and increase profit, citing ‘changes in the global trade policy and new or increased tariffs,’” reports the Guardian.

For Vox, Lee Drutman talks with a political scientist who determines that the United States officially can be classified as an oligarchy.

“Congressional Republicans are advancing health care proposals that would make coverage more expensive and less accessible for millions of Americans,” write Natasha Murphy and Andrea Ducas at CAP. “Specifically, their plans would impose higher costs on American families by slashing Medicaid funding and by allowing the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) enhanced premium tax credits to expire.”

This Week in Middle-Out

“During the COVID-19 recession, the Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) helped fuel a fast recovery,” writes Dave Kamper at EPI. “The fiscal recovery funds provided to state and local governments were critical to that recovery. Some of those states, cities, and counties did more than just support an economic recovery—they made wise investments that will help lessen the harms of the next recession in their communities.”

California is such an economic powerhouse that for years it stood on its own as the fifth largest economy in the world. This year, the state of California narrowly edged out Japan to become the world’s fourth-largest economy—and it did so as a state with a high minimum wage, some of the strongest environmental protections in the nation, and other middle-out economic policies in place.

The Roosevelt Institute published a great post explaining policies that progressives could enact to lower prices for consumers.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Nancy MacLean’s book Democracy in Chains is required reading for anyone who cares about political economy. It details the secret conspiracy that created trickle-down economics. This week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics revisits the conversation that Goldy and Nick had with MacLean back in 2020—a conversation that is more relevant today than when it originally aired.

Closing Thoughts

On Tuesday, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick defended the Trump Administration’s tariff program on CNBC. Specifically, Lutnick falsely argued that tariffs would bring manufacturing back to the United States. Much has been written about how the tariffs are actually discouraging manufacturers from investing in America, so I won’t belabor that point here. Instead, I wanted to focus more broadly on something that Lutnick said that reveals his economic philosophy:

"It's time to train people not to do the jobs of the past, but to do the great jobs of the future,” Lutnick said. “This is the new model where you work in these kinds of plants for the rest of your life and your kids work here and your grandkids work here."

Some 13 million Americans work in manufacturing, and they’re doing important work that should be celebrated. And America should continue to invest in manufacturing using smart legislation like the CHIPS Act, which addressed a yawning gap in both our economy and our national security.

First of all, we need to make clear that the factory jobs that Lutnick is evoking were considered good jobs during the 20th century because unions forced corporations to provide good-paying and safe jobs. The Trump Administration is continuing the trickle-down trend of stripping power away from unions and workers, meaning that these hypothetical factory jobs Lutnick is talking about creating are likely to be low-wage, at-will employment.

But my goodness, Lutnick’s comments struck me as a fundamentally un-American thing to say. It’s more than a little shocking to hear someone who is reportedly worth three billion dollars casually admit that his dream for the American worker is to see generations of families work the same job in the same factory.

I grew up in an America in which the dream was that children would do better than their parents. Maybe they’d go to college and become a doctor or a lawyer. Maybe they’d start and grow a small business. But the idea was that parents worked hard so that future generations would have more opportunities to grow and save and build and pass on more opportunities to their own kids one day.

Over the last four decades, as wealth inequality has grown, people have stopped believing in the American dream. Now, more than half of all Americans believe that it’s unlikely children will do better than their parents. Lutnick seems to be offering a new American Dream to workers—one that trades aspirations and opportunities for static generational job security. If you’re the son of a machine operator at a Buick plant, you’re going to be a machine operator at a Buick plant, and your children will grow up to be machine operators at that same Buick plant.

So let’s examine this sales pitch from an economic standpoint. We know that 21st century economies grow as they change—particularly through innovation and combinatorial action. Fifty years ago, IBM was one of the biggest companies in America. A hundred years ago, General Motors was the most valuable company in the nation. That evolution is a feature of economic growth, not a bug. Businesses compete and succeed and fail, and new ways of working and living grow up to take the place of the failed businesses, generating wealth as they go.

A couple of months ago, Yoni Appelbaum made a compelling case on an episode of Pitchfork Economics that physical mobility—the movement of people from one part of the country to another in search of opportunities—is actually a driver of America’s economic growth. (Appelbaum’s book Stuck explains this concept in great detail and highlights the troubling fact that mobility has been on the decline in America throughout the trickle-down era.)

Most importantly, you want to include the most people possible in your economy as participants—as workers, as consumers, as creators of businesses and members of their communities. When people don’t feel empowered to participate, the economy shrinks. Generations of Americans working in the same place, handing down jobs from parent to child like family heirlooms, is a recipe for disastrous economic contraction.

And finally, setting aside economics for a moment, Lutnick’s pitch brings two major questions to mind. First, does Lutnick really believe he’s presenting an aspirational goal for most Americans? And second, what does Lutnick himself want for his own children? A Fortune headline from not long after Lutnick took his job as Commerce Secretary answers that second question:

“Brandon, 27, is now CEO and chairman, and Kyle, 28, executive vice chairman of the parent company that controls investment bank Cantor Fitzgerald & Co., brokerage BGC Group Inc. and commercial real estate firm Newmark Group Inc,” Fortune reports. “And they’ll be key players in the crypto world, thanks to Cantor’s expansive work in the sector and its alliance with Tether Holdings Ltd.”

The story explains that Lutnick handing his investment bank over to his sons “inaugurate[s] a new dynasty on Wall Street, where control of investment banks was once regularly passed from generation to generation.” So one could argue that Lutnick is practicing what he preaches—though of course unlike the factory jobs Lutnick praises, the jobs he’s handing to his sons will likely provide access to millions, and potentially billions, of dollars in wealth over their lifetimes.

I don’t begrudge anyone doing a hard day’s work—every job has its own dignity. But I also believe that most parents want more for their children than what they have. And an economy in which wealthy children get handed the keys to daddy’s kingdom while generations of workers toil with no hope of better outcomes is exactly the kind of system that our forefathers fought against in the American Revolution.

Be kind. Stay strong.

Zach