Friends,

Some of the wealthiest people in the world made their way to Switzerland this week to take part in the annual World Economic Forum at Davos. The WEF doesn’t describe itself as the world’s most exclusive networking opportunity or a chance for CEOs, world leaders, and the super-rich to brag about their past year’s achievements—though it is both of those things. As New York Times reporter Peter S. Goodman explained on Pitchfork Economics last year, the WEF is pitched to attendees as a conference to discuss how an elite class of wealthy people can save the world.

To give you an idea of how out-of-touch the WEF is, one of the major topics of discussion at this year’s conference is cryptocurrency. Abha Bhattarai at the Washington Post reports that there are no less than seven different panels for elites to discuss the possibilities of crypto and the blockchain as a solution for the world’s economic woes, even after cryptocurrencies collapsed repeatedly in full public view over the last year.

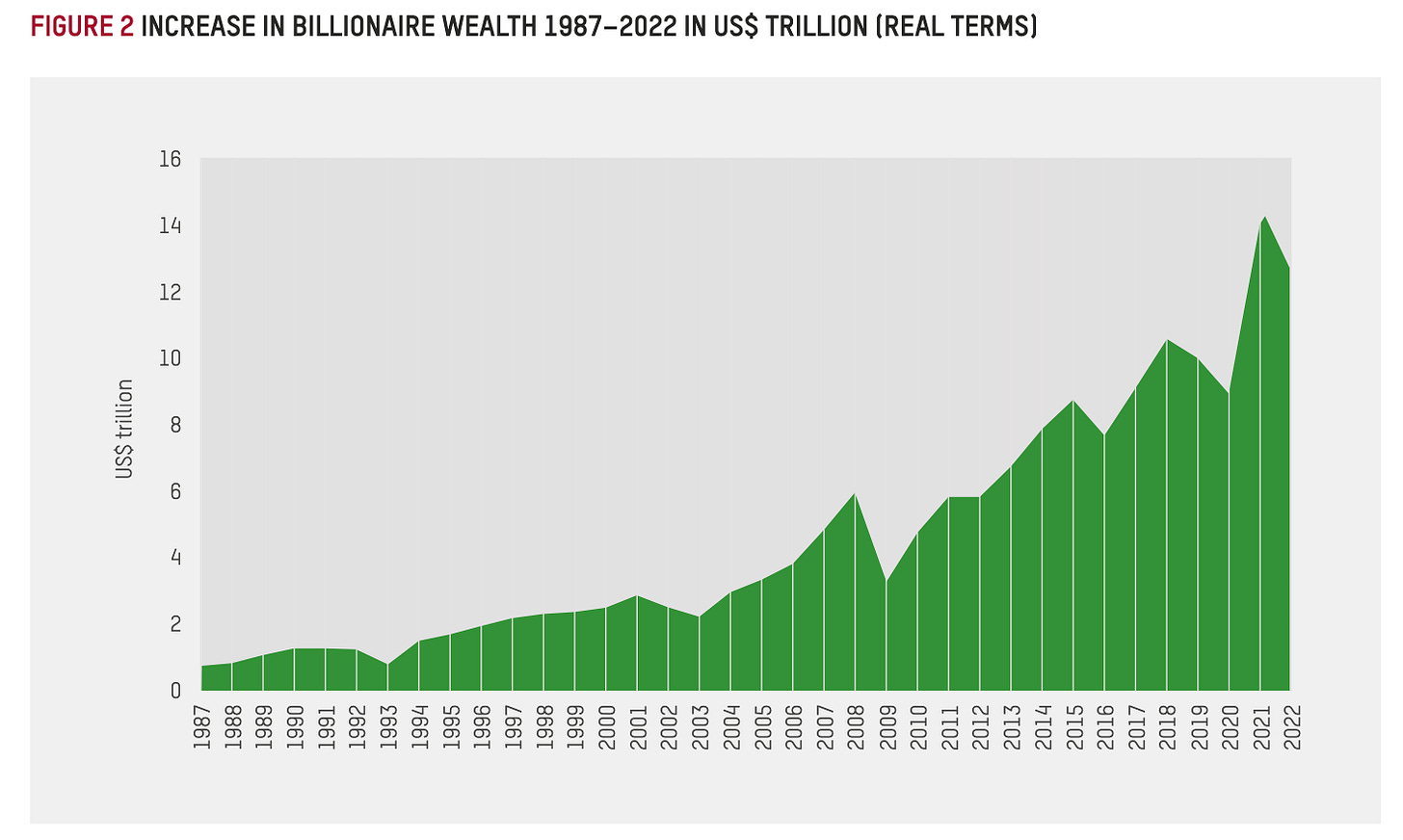

One problem that won’t be seriously discussed at Davos this year is wealth inequality. Oxfam International celebrated the first day of the WEF by releasing a report proving that inequality has accelerated since the beginning of the pandemic. “Since 2020, the richest 1% have captured almost two-thirds of all new wealth – nearly twice as much money as the bottom 99% of the world’s population,” Oxfam reports.

The charts included in the report are breathtaking in how plainly they lay out the growing problem of hyper-accumulated wealth:

This kind of wealth inequality is bad for everyone. It increases poverty, engenders political unrest, and creates a class of elites who are above the law and free from repercussions. And the solution to this problem doesn’t involve cryptocurrency or any of the other convoluted ideas floated at this year’s WEF panels.

Dutch historian Rutger Bregman famously promoted a real solution to inequality at Davos in 2019. “Just stop talking about philanthropy and start talking about taxes,” Bregman announced on a panel. “We’ve got to be talking about taxes. That’s it. Taxes, taxes, taxes. All the rest is bullshit in my opinion.”

The moment went viral and Bregman became a star, but his solutions didn’t gain purchase with the Davos crowd. Instead, they return again and again to the idea of philanthropic giving as a cure-all, even while Oxfam estimates that taxes on the wealthy account for only four cents of every tax dollar collected around the world.

But change is in the air. Bregman’s criticism was the first drop in a growing flood that the Davos crowd ignores at their peril. Now every year, when the WEF meets at Davos, media-savvy organizations and individuals use the gathering as a teachable moment to get the word out about wealth inequality and its role in global poverty rates, and how a balanced tax code could solve many of the problems that the WEF grandly frets over once a year. This genie is not going back into the bottle.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The debt ceiling debate is an unnecessary, manufactured crisis

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen announced last week that the Biden Administration would begin to reprioritize federal funds if House Republicans failed to raise the debt ceiling by today. “The emergency moves ultimately could give Democrats and Republicans until at least early June to adopt a law that would raise or suspend the country’s borrowing cap beyond its current level of $31.4 trillion,” write Jeff Stein and Tony Romm at the Washington Post.

Yes, there’s a Democratic president and a Republican-run House, which means the American economy is going to be held hostage by a handful of Republican congresspeople who suddenly care deeply about deficit spending. (They had no such concerns when President Trump added roughly $8 trillion to the debt in his single term, about half of which was incurred before the pandemic to help fund his tax cuts for the wealthy.) The debt ceiling battle is a moronic partisan game of chicken, but its potential repercussions are no laughing matter—failure to pay our debts could sink the American economy.

Robert Kuttner at the American Prospect warns that House Republicans even hinting at creating a crisis around the debt ceiling has its costs: “In 2011, Republicans in Congress used the debt ceiling as leverage for deficit reduction,” Kuttner explains. “The delay in getting the deal done resulted in a credit downgrade of U.S. Treasury debt. According to the Bipartisan Policy Center, the delay raised government borrowing costs by $18.9 billion over ten years.” And some of the spending cuts that Republicans managed to extract during that last debt-ceiling debacle were reversed soon after, when the public realized the harm those cuts would cause to important services.

Kuttner also offers several ways for the Biden Administration to get around a debt ceiling crisis, including a potential constitutional workaround or even a shutdown of the federal government. At the New Republic, Jason Linkins endorses an even sillier workaround involving the minting of a single trillion-dollar coin to fund the government through the crisis.

But it’s preposterous that the Biden Administration should even be forced to seriously consider any of these avenues. The debt ceiling debate is as silly and unnecessary today as it was during the Clinton and Obama administrations—it’s partisan grandstanding over an issue that doesn’t matter. If House Republicans were truly serious about bringing the debt down, they could support the Biden Administration’s call on a global minimum tax, which would vastly increase revenue and decrease our need to borrow money to fund important programs. Instead, Republicans worked with Hungarian leader Viktor Orban to sabotage the global minimum tax.

If the media behaves as it has in the past, reporters will cover the debt ceiling crisis under a good-faith assumption that both sides have relevant points, and they’ll equally attribute blame to both Democrats and Republicans. I’d suggest that this isn’t responsible journalism, and that if the media truly wanted to cover the debt ceiling in a useful way, they would ignite a national conversation about government finances—how a relentless campaign of tax cuts resulted in increased borrowing, and why taxing wealthy people and corporations at the same level that ordinary Americans are taxed would improve the economy for everyone.

Mixed economic signals persist

Retail sales fell 1.1% in December, indicating that Americans tightened their belts before Christmas shopping. This is no surprise, considering that American consumers had been confronted with months of warnings in the media that we could be entering a recession at any moment. That drop in spending in the all-important holiday shopping season signaled the death knell for several troubled retailers, including Party City and Bed, Bath and Beyond.

Meanwhile, big banks are socking away billions of dollars into reserves in case the economy does dip into a recession. Stacy Cowley and Rob Copeland report for the New York Times that JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo are all preparing for the possibility of what they characterize as a “mild recession,” though JP Morgan Chase’s CEO Jamie Dimon demonstrated uncharacteristic humility when he admitted “we don’t know the future” and warned that his experts said signs of a global economic downturn “may go away or they may not.”

Many of the worst economic indicators we’re seeing right now are the ones based on feelings and expert predictions. And that’s perfectly normal, given that none of us have ever lived through a global pandemic and its resulting surge of inflationary pressures. Nobody knows what to expect. But the concrete numbers to watch are still the monthly unemployment numbers and real wages of American workers. And right now, those numbers are still good.

Inflation numbers are pointing in the right direction, too. The Producer Price Index—which tracks the prices that producers charge manufacturers and distributors—slowed steeply in December.

This is a good sign for future monthly inflation reports because it indicates that prices are decreasing at their source. Manufacturers, distributors, and retailers might add their own price increases further downstream, but those price increases would be obvious and could result in serious consumer backlash.

Tracking the pulse of the American worker

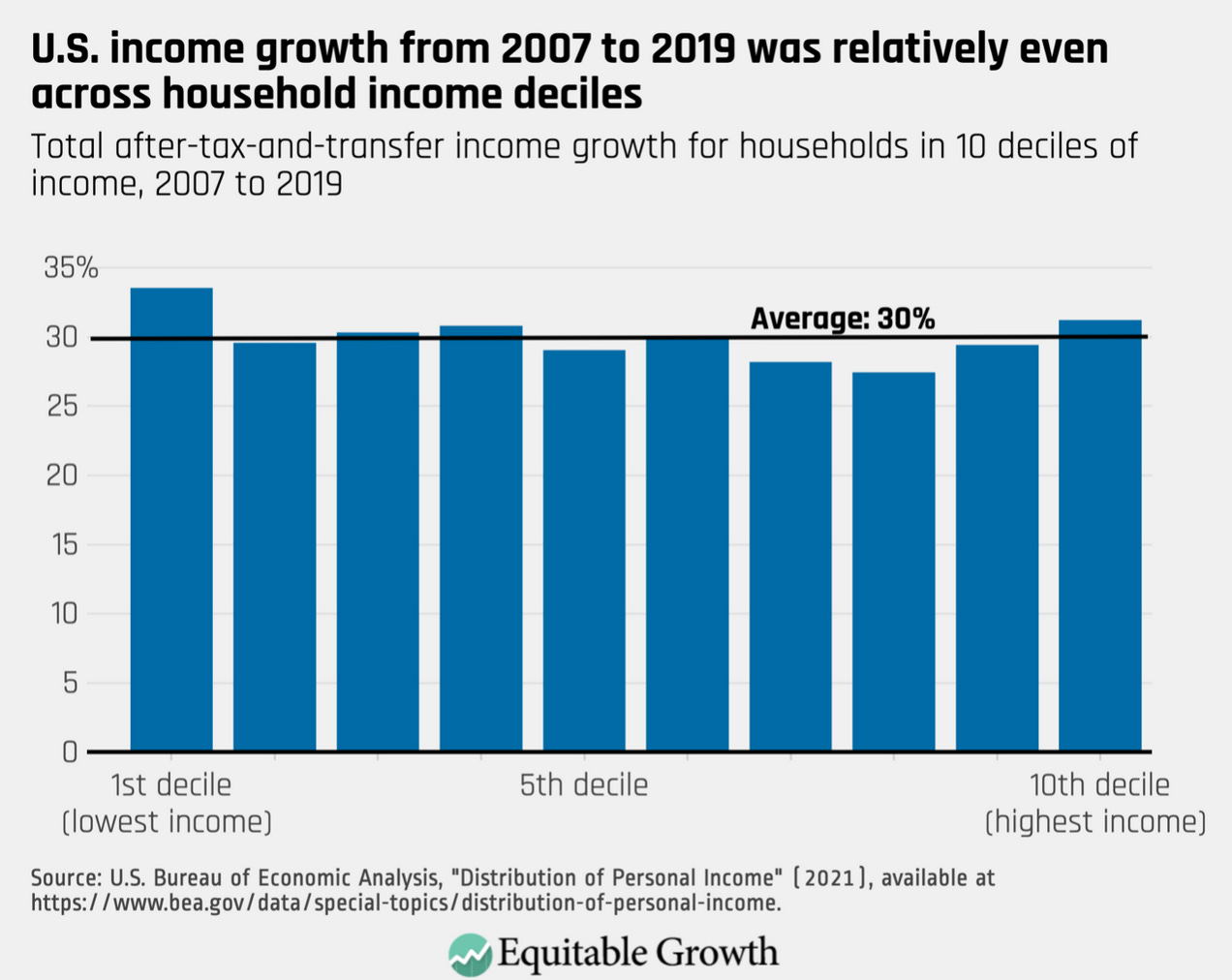

Austin Clemmons’s recent report for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth offers some good news in the fight against economic inequality in America. He calculates that income growth was steady across the economy from 2007 to 2019, meaning that wealth inequality basically stayed stable or even slightly declined from the Great Recession through the beginning of the pandemic.

Clemmons also finds that income inequality decreased at never-before-seen levels since the pandemic began. That’s good news, but Clemmons chases it with some bad news: The gains that low- and middle-income Americans saw in this time mostly came in the form of government programs like “the expanded Child Tax Credit, enhanced Unemployment Insurance, and direct stimulus checks,” all of which have since expired and show no signs of returning anytime soon.

Meanwhile, a new study from Harvard economist Raj Chetty finds that 2.6 million low-wage American workers are missing from the workforce, and they’re missing in areas populated by the wealthiest Americans and in areas that closed down most completely at the beginning of the pandemic:

When low-wage employment is plotted on a graph by county, the highest-rent areas are missing the most workers — the places where bars, restaurants and health clubs were most empty in 2020. Chetty, along with professors John Friedman of Brown University, Nathaniel Hendren of Harvard and Michael Stepner of the University of Toronto, write the “strongest predictor” of the drop in employment is “the size of the initial shock.”

There could be a number of reasons for this disappearance: Workers might have moved to places where the rent was more affordable, or perhaps they aged out of the workforce during lockdowns, or perhaps long Covid is preventing them from rejoining the workforce, or maybe this is due to a large swath of the labor force working from home and not needing service workers in expensive downtown areas. But the report offers a bracing reminder that we don’t fully understand the shape and size of the American workforce, and the pandemic leaves many lingering questions.

Some other labor news from this week that caught my eye:

Apple will conduct a review of its labor practices in the United States “with a coalition of investors that includes five New York City pension funds.” Specifically, the review will determine if Apple’s dealings with unions are in line with its stated international human rights policies.

A lack of public investment in the care economy has resulted in high-income families bidding up prices on services like daycare, nursing homes, and preschool. This has created a different kind of inflation for low-wage workers with young children or older or infirm relatives, pushing them out of the economy—and those high prices don’t even result in higher wages for care workers.

The Economic Policy Institute issued a report showing that abortion bans disproportionately affect low-wage workers, stripping them of power and limiting their options for employment. Indeed, states with low minimum wages and union power are far more likely to have aggressive abortion bans on the books.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

This week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics is a change of pace: A conversation with sci-fi novelist Kim Stanley Robinson about his most recent novel, a near-future thought experiment titled The Ministry for the Future. It’s a genuine pleasure hearing Nick and Goldy geek out about economics with Robinson, who uses his book to sketch out a new type of economics that helps to curb climate change.

On Civic Action Live this week, we’ll discuss how the elites at Davos could actually save the world, what to make of the latest crop of confusing economic indicators, and the latest developments in the debt ceiling drama. Join us at 10:30 am PT tomorrow.

Closing Thoughts

If you’re looking for a good roadmap of the year ahead in policy and politics, the American Prospect’s David Dayen laid out a prediction for 2023 that seems directionally correct to me. While the media will likely remain fixed on the partisan gridlock that seems sure to unfold in the House, Dayen writes that “the business of governing will move inside the conference rooms and offices in executive branch agencies, where the business of interpreting and executing laws will be priorities.”

Because Speaker McCarthy can’t seem to get a coherent lunch order out of his razor-thin majority, much less meaningful legislation, it seems obvious that rulemaking and executive actions will be the prime movers of political action this year. Now is the time for the policy wonks of the Biden Administration to shine. Dayen writes,

More decisions to improve lives will be made on a daily basis by the executive branch in 2023. Unheralded people like Gabe Klein, who runs the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation that will manage $7.5 billion in electric-vehicle charging station funds, or Jigar Shah, who runs the Loan Programs Office at the Department of Energy and has up to $100 billion in lending capacity for green-energy projects, will simply matter more in the overall scheme this year than Marjorie Taylor Greene or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

And in fact many of these rules have already entered the pipeline. I wrote last week about the importance of the Biden Administration’s proposed noncompete rules, which would encourage competition in the labor market for American workers and increase paychecks by an estimated $300 billion per year. And Dayen lays out a few more rules that are already underway:

Proposed rules would more closely scrutinize television advertising and other aggressive marketing for private Medicare Advantage plans, which have been accused of denying patients care and overcharging the government. The Environmental Protection Agency finalized a Clean Trucks rule that could significantly reduce pollution in vulnerable areas with heavy traffic. Federal drinking water standards seek to eliminate the dangerous “forever chemicals” known as PFAS from the water supply. The drinking water standards are already bearing fruit, as 3M has announced it would discontinue use of PFAS.

There will be plenty more proposals to come this year. Personally, I hope the Biden Administration will deliver a restored overtime threshold, for instance, and the Biden Administration just placed a prominent anti-monopoly crusader in a high-level role at the Department of Transportation, which is a hopeful sign. We’ll write about these developments here in The Pitch as they’re unrolled. But Dayen points out that detailed policy reporting isn’t exactly the strong point of the American media, which focuses more on outrageous personalities than it does on policy outcomes.

This is where you come in. When you see a piece of reporting that focuses intelligently and soberly on policies—we link to several every week in this newsletter—it’s important to share that piece far and wide on social media, to ensure that decision-makers at online publications understand we want more in-depth analysis and explanations in our news coverage. And it might seem silly, but it’s also important to write directly to journalists who do good work and let them know you appreciate them. One brief personal note of praise means more to the human beings who produce the news than ten thousand thumbs up on Facebook.

A lot of meaningful things are going to happen this year, but our media has become so algorithmically twisted over the past decade that it will be hard to get the word out about those advances, and why they matter. It’s not enough to craft and implement good policy—people have to know the policy exists. We need journalists and storytellers who remember that the purpose of government isn’t to win elections, it’s to improve the lives of citizens. So for 2023, let’s make the resolution to remember one simple fact: Politics is the sideshow; policy is the main attraction.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach