Friends,

On Monday, Google lost a four-year-long court battle with the United States Department of Justice. "Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly,” wrote US district judge Amit Mehta in his ruling.

One of the key pieces of evidence that Judge Mehta uses to label Google a monopoly is from a study that Google commissioned. "In 2020, Google conducted a quality degradation study, which showed that it would not lose search revenue if were to significantly reduce the quality of its search product,” Mehta writes. “Just as the power to raise price 'when it is desired to do so' is proof of monopoly power, so too is the ability to degrade product quality without concern of losing consumers."

Mehta’s findings specifically labeled Google a monopoly in internet search—he ruled against DoJ accusations that Google had a monopoly over advertising within searches, for instance. The smoking gun in terms of Google’s search monopoly, Mehta concludes, comes from the fact that Google spends billions of dollars to ensure that it is the default search engine on a wide array of devices and services.

At Ars Technica, Ashley Belanger writes that Mehta “found that Google's exclusive distribution deals foreclosed a ‘substantial share’ of the markets and allowed Google to earn more revenues. Google then shared spiking revenues with device and browser developers—spending up to $26 billion in 2021 alone for exclusive deals.”

In the end, Mehta concludes, "The key question then is this: Do Google’s exclusive distribution contracts reasonably appear capable of significantly contributing to maintaining Google’s monopoly power in the general search services market? The answer is 'yes.'"

It’s not clear exactly what happens next for Google. “Judge Mehta will now decide that, potentially forcing the company to change the way it runs or to sell off part of its business,” writes David McCabe at the New York Times.

“Legal scholars expect this decision to influence government antitrust lawsuits against the other tech giants,” McCabe adds.

“The Justice Department has sued Apple, arguing that the company made it difficult for consumers to ditch the iPhone, and brought the other case against Google,” McCabe writes. “The F.T.C. has separately sued Meta, claiming the company stamped out nascent competitors, and Amazon, accusing it of squeezing sellers on its online marketplace.”

This is nowhere near the end of this story—Google will appeal Mehta’s verdict and do everything in its power to slow-walk any judicial actions—but it’s an important development. Mehta has opened the door to ruling against Big Tech corporations, establishing a precedent that others can follow.

For his newsletter about monopolies, BIG, Matt Stoller writes that this decision will have wide-ranging effects: “Exclusive contracts and arrangements are pervasive in American commerce, and until recently, executives could reliably exploit such deals without fearing that they might face any legal liability. But that era is over,” Stoller writes.

“This case is in the headlines, which means every single competent executive in America in any firm with market power is going to get a memo from their antitrust or general counsel on what they can and can’t do going forward,” Stoller continues. “And they will likely begin changing their behavior to avoid being brought to court for monopolization.”

In other words, this is a big deal—a huge step forward in the fight against corporate consolidation.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The Labor Market Is Cooling, and the Fed Is To Blame

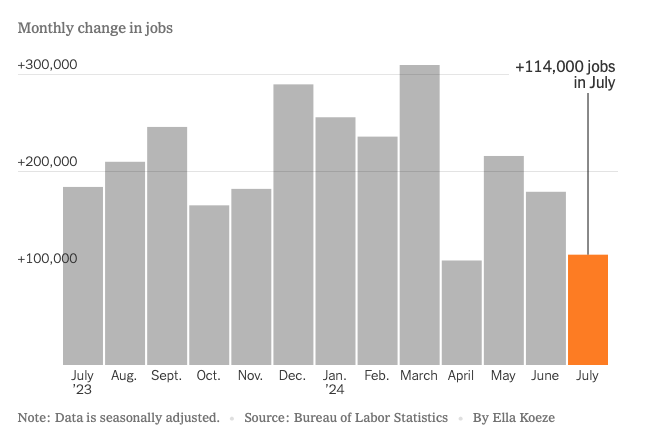

Last Friday saw the unemployment rate raised to 4.3%, with 114,000 jobs added to the economy. It was the weakest jobs report since October 2021. Last Friday and this Monday, the stock market dropped by roughly 3%, which many commentators attributed to the jobs report. But that accusation doesn’t stand up to reality: Stock markets dropped around the world, led by a 12% drop in the Japanese stock market due to some complex currency trading shenanigans. The stock market, regular readers of The Pitch know by now, is not an accurate representation of the economy’s health. It is at best an occasional window into how the wealthiest Americans are feeling at any given moment—and at worst it is, as Dr. Justin Wolfers wrote yesterday, “a toddler tantrum.”

The jobs report immediately set off alarm bells with economists who warned of a potential recession on the horizon—though we have to keep in mind that many of those same economists have been ringing alarm bells about impending recessions intermittently since President Biden took office in 2021. And remember that the economy is still behaving strangely due to the aftereffects of massive pandemic disruptions: For instance, Angry Bear blog notes that the most recent Fed’s Senior Loan Officer survey—a quarterly study that measures demand for loans—is acting in a positive manner that more closely resembles the behavior that happens in the months after a recession, not right before a recession. And just today, new unemployment claims came in significantly below economists’ expectations, which eased fears about a sudden plunge in the labor market. As one economist told Investopedia this morning, "If you’re looking for additional weakness in the labor market, you’ll need to find it somewhere else.”

Many economists placed the blame for last month’s jobs report directly at the feet of the Federal Reserve. Moody’s Analytics economist Mark Zandi, for instance, minced no words in his tweet after the report was released: “The clear message in today’s soft jobs report is the Federal Reserve needs to cut interest rates. They should have begun cutting rates months ago,” Zandi wrote.

“Job growth is decidedly throttling back, unemployment is rising quickly, hours worked per week are low and falling, and temporary help jobs continue to evaporate,” he continues. “Wage growth and inflation are back to the Fed’s target.”

Zandi concludes, “The question isn’t whether the Fed should cut in September, but by how much.”

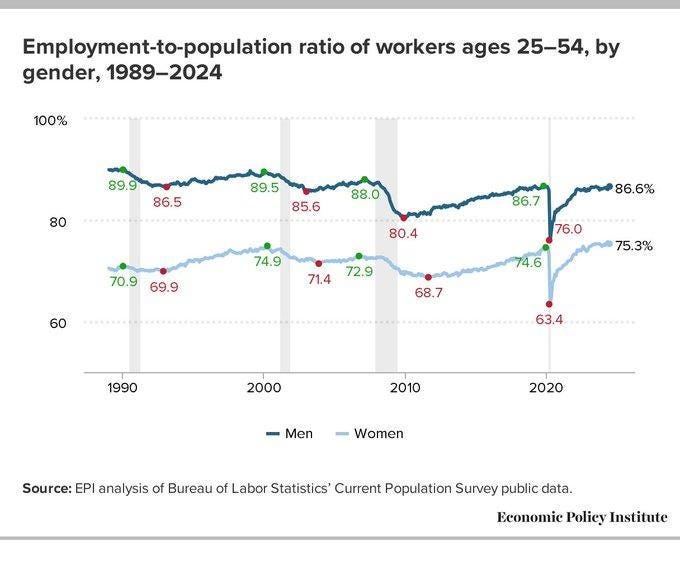

The employment report wasn’t all bad news. EPI economist Elise Gould writes that employment among men and women aged 25-54 increased last month, with men in that prime age group near pre-pandemic employment highs and women reaching all-time employment levels.

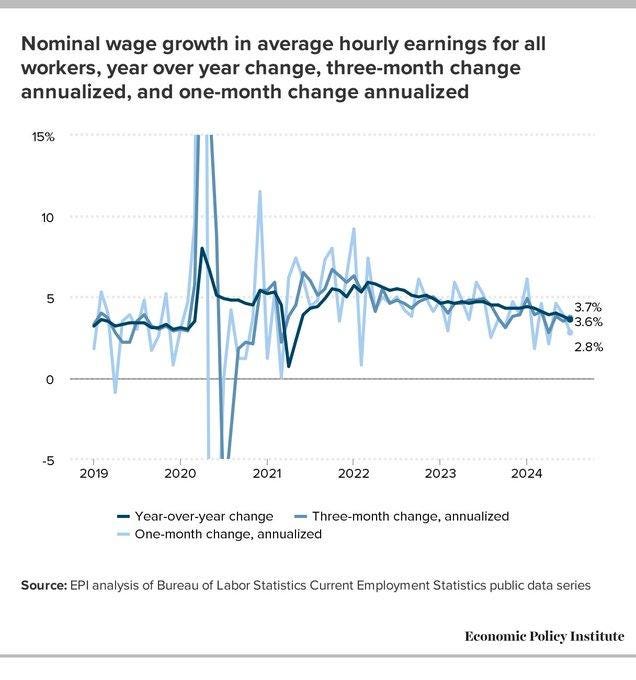

But the number that we’re most concerned about also declined: Worker wages continued to dip.

“Wage growth decelerated in July, with average hourly earnings up 0.2 percent from the previous month and 3.6 percent from a year earlier,” writes Sydney Ember at the New York Times. “The number of people working part time who would have preferred full-time employment also increased, while the number of hours worked per week ticked down slightly, both signals that the demand for workers is slackening.”

Because the wages of working Americans are what power the economy, our leaders should be doing everything they can to ensure that Americans have access to jobs, and that their paychecks are growing. The first step—a long overdue first step—is for the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, making housing and credit more affordable, and giving businesses the confidence to expand and take more risks. They’re expected to do just that during their meeting next month, and many economists including Paul Krugman and David Rosenberg argue that the Fed’s refusal to lower rates earlier is actively harming workers. And when you harm American workers, you’re harming the American economy.

The Big Question: How Can We Keep Paychecks Growing?

In the first sentence of yesterday’s story about the ongoing recession panic, The New York Times correctly identified the source of America’s economic strength: “The economy’s resurgence from the pandemic shock has had a singular driving force: the consumer.”

Rachel Siegel at the Washington Post agrees: “Consumer spending — which makes up roughly 70 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, a measure of the size of the overall economy — has stayed solid through it all.”

Those consumers were buoyed by an incredible wave of wage growth and worker confidence that followed the return to work after Covid lockdowns were lifted. But now the labor market is looking a little less solid than it was.

That’s bad news, considering that the most important economic metric right now is the health of the American worker. “Despite contortions in world markets, many economists are cautioning that there is no reason to panic — at least not yet. In July, there was a notable slowdown in hiring and a jump in the unemployment rate to its highest level since October 2021, but consumer spending has remained relatively robust,” the Times notes. “Wages are rising, though at a slower rate, and job cuts are still low.”

So now, the Times reports, many of the companies like Frito-Lay that recklessly raised prices far higher than inflation in order to gouge customers and stoke record-high profit margins during the greedflation craze are nervously watching their sales numbers and the job market. They’re hoping that consumers will continue to hold the American economy aloft.

That’s why workers are demanding better pay and working conditions. “About 13,500 hotel workers across Boston, Honolulu, Providence and San Francisco will vote on whether to strike this week as they push for significant wage increases and protections against job cuts,” writes Michael Sainato at the Guardian. “Employees at leading chains including Hilton, Hyatt, Marriott and Omni will decide in the coming days whether to approve the walkouts.”

Those hotel workers can look to an unlikely union for inspiration: Workers in Maryland became the first US Apple Store to unionize. The New York Times reports that workers successfully negotiated for a 10% raise and guaranteed benefits and severance pay. It’s an important milestone because it gives other Apple Store staff—including workers at an Oklahoma City Apple Store who voted to unionize—a precedent to point to as they negotiate with Apple.

Those bigger paychecks aren’t a bonus for workers—they’re an absolute necessity. While prices aren’t skyrocketing like they were two years ago, the fact remains that grocery stores, restaurants, and retail shops are still taking a bigger bite out of worker paychecks than they were in pre-pandemic times. While paychecks grew higher than prices, those wages are now starting to level out, meaning that workers don’t have the cash to squirrel away for a rainy day.

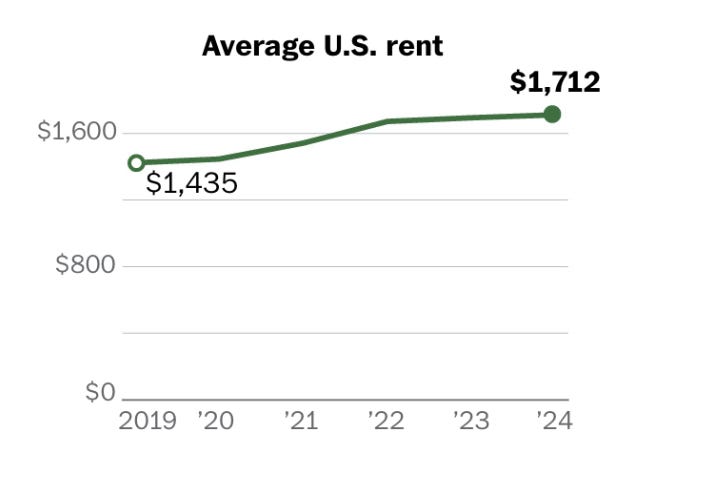

Much like other prices, housing costs have largely leveled out, but they are still much higher than they were before the pandemic. “Though rent prices nationally have climbed about 19 percent since 2019, prices increased only about 1 percent in the past year, The Washington Post reports. The average US rent is now $1712 per month, compared to the 2019 average rent of $1435. While that slowdown is good news, it’s yet another price that has significantly increased for workers.

I recommend going over to the Post and looking at the interactive map showing rent increases by county. In my home of King County in Washington state, for instance, the average rent is now $2083, and rents have gone up 2.6% in the last year and 15.8% in the last five years. Those kinds of increases make it hard for workers to improve their living conditions—at best, they’re just treading water and at worst they’re putting extra expenses on credit cards and postponing economic hardship for another day.

In order to keep the economy humming, workers need policy interventions to help with this housing price crisis. Vox reports on Vice President Harris’s embrace of a proposed Biden Administration policy which would discourage corporate landlords from raising rents by more than 5%. The piece reports that a number of economists believe that rent control is a bad idea, but none of those neoliberal economists directly interact with the Biden proposal, which doesn’t outright ban large rent increases but rather just disincentivizes them by making large landlords who raise the rent more than 5% ineligible for federal tax breaks. Broadly arguing that “everyone knows rent control doesn’t work” is a trickle-down statement that enriches the wealthy at the expense of renters.

After all, as both the New York Times and the Washington Post reported this week, wealthy corporate landlords don’t keep the economy growing—American consumers do. For too long, we’ve let trickle-downers dictate that housing should be bought and sold in a free, unregulated market where landlords get to charge “whatever the market will bear.” It’s time to make a serious investigation of what a truly middle-out housing plan can and should look like, and the Biden-Harris corporate-rent cap plan is a solid start.

This Week in Middle-Out

That Google monopoly verdict that I wrote about in the introduction is far from the only case that the federal government has brought against Big Tech’s competition-killing market consolidation. The New York Times notes that “the Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission started investigating Amazon, Apple, Google and Meta, the parent company of Instagram and WhatsApp, for monopolistic behavior,” and they run down the status of each of those cases.

Now, many are wondering if chip manufacturer Nvidia, which manufactures 90% of the chips that power artificial intelligence, might wind up with a monopoly case of its own. “The Justice Department has also started investigating Nvidia’s sales practices and will review one of the company’s most recent acquisitions,” reports the New York Times.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau is now investigating big banks like Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase to determine whether they’re doing enough to prevent scams involving the money-transfer app Zelle.

The Center for American Progress reports that while the Biden Administration’s student debt relief programs keep getting intercepted by conservative judges, the Administration is revising its student loan forgiveness plan into a “Plan B” that offers several wide-ranging avenues toward forgiveness. Some of the new strategies include forgiving debts older than 20 years and automatically giving forgiveness to eligible debtors who haven’t yet applied for relief.

And CAP also offers a thoughtful paper suggesting policies that will help economically empower single mothers. It’s a wonderful overview of the policies that have been proven to improve outcomes for single moms, like reforming TANF, raising the minimum wage, and restoring the Child Tax Credit.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

This week is the return of a beloved annual Pitchfork Economics summer tradition: Goldy and Paul talk about some of the best and most interesting economic books they’ve read this year in a summer reading list extravaganza. Be sure to check out the shownotes, which includes links to all the books discussed in this week’s episode.

Closing Thoughts

This week, mainstream political pundits had a strange response to Vice President Harris’s announcement of Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her choice for the Democratic vice presidential candidate. Commentators like Nate Silver, Nate Cohn, and other people not named Nate all recoiled in shock that Harris would choose a “far-left” politician, rather than select someone who would move the ticket more toward the political middle.

The clearest example of this particular pundit complaint is New York Magazine’s Jonathan Chait, who published a piece titled “Kamala Harris and Tim Walz Need to Pivot to the Center Right Now.” In the piece, Chait argues that Walz’s selection “forfeit[s Harris’s] best opportunity to send a message that she is a moderate. She needs to take every possible opportunity between now and November to make up for that.”

This take offers an important opportunity to talk about the pundit-fueled fiction of the “political center,” an imaginary realm that somehow exists directly in the middle of every single partisan policy. To hear Chait and Cillizza and the professional pundit class tell it, the center is somehow a place where all Americans are satisfied, politicians have high approval ratings, and nobody ever disagrees.

These pundits argue that Walz is way out on the loony left fringe, far away from the center, and he will be judged unpalatable by the majority of voters who consider themselves true centrists.

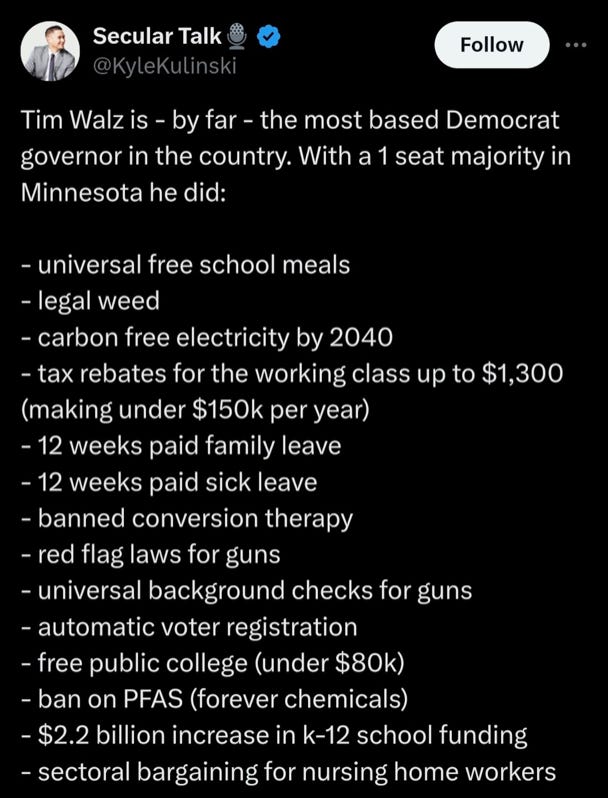

But let’s look at Walz’s record as governor, which was summed up in a tweet that went viral during Harris’s VP selection process:

There is not a single off-putting idea on this list. The vast majority of Americans want paid family and sick leave, free lunches for kids, and universal background checks. Most voters want kids to have a shot at affordable education. And Americans overwhelmingly love unions and want to make them stronger. These aren’t “liberal” policies—they’re incredibly popular policies that broadly benefit a wide swath of working Americans.

Back in 2018, Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer wrote a piece for Politico titled “Democrats Must Reclaim the Center … by Moving Hard Left,” in which he claimed that “America needs a centrist party that actually represents the economic center, not just zillionaires like me.”

Nick correctly argues that any policy which is favored by and which benefits the broad majority of Americans is by very definition a centrist policy. And he explains how centrist-brained pundits like Chait and Cillizza have become so misguided:

Imagine lining up every person in America on a yardstick, with the poorest person standing to the far-left edge of the stick (zero inches) and the wealthiest person standing to the far right (36 inches). Assuming that people are equally spaced, and that there is no correlation between wealth and weight—if you could balance that yardstick on the tip of your finger, the fulcrum would fall on the 18-inch mark, the exact center of the yardstick, with exactly half of all Americans standing to the left, and the other half standing to the right. Clustered on and near that 18-inch mark are the median American families—the middle-middle class—the majoritarian center of the American electorate, at least from an economic perspective.

Now imagine that very same yardstick with every American standing in their very same spots—only this time, rather than balancing people, we are balancing their personal wealth, stacked up in $100 bills. But because 2 percent of Americans (of which I am one) own 50 percent of the nation’s wealth, to balance this yardstick you’d now have to slide your finger nearly all the way over, beyond the 35-inch mark, just inside the far-right edge. This fulcrum balances the interests of capital, not people. And unfortunately, this is the yardstick of our current ideological center—a centrism informed by the bad economic theories that have guided the policies of both parties for more than 30 years.

So in sum, when you see high-profile pundits talk about how Walz is out of step with the political center, they’re actually arguing that he’s out of balance with the center of America’s wealth as it is currently distributed, in which a tiny fraction of the population hold the majority of the nation’s wealth.

Instead, Walz’s policies are invested in the majority of working Minnesotans, enabling them to fully participate in the economy and workers, consumers, and neighbors. That’s why Minnesota has a high average annual income—$77,706, according to a recent study—and one of the lowest poverty rates in the nation. They’re policies that benefit everyone, including the wealthy few.

Nine times out of ten, when you see someone on cable news or in print complaining about a politician leaving the center behind, they’re not arguing on behalf of the American people—they’re arguing for the preservation of America’s obscenely concentrated wealth.

It’s important to call out this kind of trickle-down defense mechanism every time you see it. Popular policies are popular with a broad majority of Americans regardless of party, and don’t let any pundit tell you otherwise.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach