Friends,

Next year, major pieces of the Trump Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which gave trillions of dollars away to the richest people and corporations in America, will expire. That means the candidates who win the presidential and Congressional elections in 2024 will get to shape the immediate future of the federal tax code.

“Biden proposes to raise corporate rates from 21 percent to 28 percent — still below the 35 percent rate Trump’s 2017 law cut it from — and preserve the Trump-era tax cuts for individuals earning less than $400,000, including a higher standard deduction,” explains Jacob Bogage of the Washington Post. “Trump, meanwhile, told business leaders this month that he hopes to cut corporate taxes to 20 percent, according to two people familiar with his remarks who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a private meeting.”

And while taxes are an important matter to consider when voting at the top of the ticket, it’s also important to remember that Congress will play a significant role in determining how the tax code will play out. Democrats in Congress right now are debating the kind of plan they want to enact, with progressive leaders like Elizabeth Warren “insist[ing] on sharp increases in the corporate tax rate and on the highest individual earners — and not to agree to any compromise with Republicans otherwise.”

“In the House, some top lawmakers are reevaluating past tax-and-spending bills that prioritized broad short-term investments that have since expired,” Bogage writes, “demanding instead that Democrats focus on bringing in more revenue from major corporations and the rich that can permanently fund a limited number of high-impact social programs.”

Some Democrats are calling for a reinstatement of the Child Tax Credit, which nearly eliminated childhood poverty in America and which spurred consumer spending, helping to power America’s first-in-the-world recovery from the supply chain disruptions caused by the pandemic. But others are arguing that another temporary reprisal of the Child Tax Credit would ultimately disappear from memory, and that the revenue from higher taxes would be put to better use permanently fortifying popular programs like Medicare, Social Security, and other safety net programs.

It’s an important question, and one that we haven’t really yet addressed in middle-out economics. We know that investing in working Americans is important, because working Americans help the economy grow. But middle-out economics is still a new enough worldview that the timing of those investments is an unanswered question. Is it better to make a big splash with a time-limited program like the Child Tax Credits, or is it more important to update programs like housing assistance and unemployment insurance by making the programs easier to access—and, hopefully, paying those investments out in the form of direct cash payments? Ideally, why not both?

Meanwhile, there is no debate on the other side of the aisle. “Trump and Republicans have pledged to renew the entire 2017 tax law. The Congressional Budget Office projects that extension would cost $4.6 trillion over 10 years, adding to an already exploding federal debt burden,” Bogage writes. “But Republicans say those tax cuts are necessary to combat the historic inflation that’s hit the economy on Biden’s watch and to keep the United States competitive internationally with countries that have lower business taxes.” This is happening even though studies show that Americans who make less than $114,000 per year saw “no change in earnings” from the Trump tax plan.

I’d love to hear a Congressional Republican try to explain how tax cuts for the rich and powerful would lower inflation. (I suspect the answer might have something to do with those savings trickling down to workers—a promise that has never, not once, ever come true.) And I’d love to hear them explain how President Biden’s proposal to raise the corporate tax rate roughly one percent higher than the average G20 corporate tax rate would ruin America’s competitive advantage and force corporations to move away from the best workforce on the planet.

The wonderful thing about democracy is that every voter is unique. We all bring our own experiences and priorities to the ballot when we vote. But unless you’re in the wealthiest one percent of all Americans, I find it hard to understand why you would find the renewal of the Trump Tax policies to be a compelling policy prescription. A vast majority of Americans now understand that a healthy economy doesn’t grow from the top down—it grows from the middle out, powered by working Americans. Shouldn’t our tax systems reflect that reality, too?

The Latest Economic News and Updates

How Housing Is Holding Inflation Up

Let’s say first, as clearly as possible, that American housing prices are unacceptable. Home prices have surged by more than 50 percent since 2019, and rents rose by just over 30% between 2019 and 2023.

For months now, I’ve been writing that America’s lingering inflation problem is actually due to high housing prices. And a new report from Christopher D. Cotton at the Boston Federal Reserve examines this phenomenon and determines that shelter prices are going to keep the inflation rate high for much longer than expected—even though rents have been coming down.

“At the end of 2023, hopes were high that falling inflation would allow the Fed to cut interest rates several times in 2024,” Cotton writes. “However, the disinflation process slowed noticeably in early 2024, prompting questions about how soon the Fed can attain its 2 percent inflation target.”

The problem, Cotton explains, is that “The price of shelter accounts for a substantial share of the indexes used to measure overall inflation—the PCE [Personal Consumption Expenditures] and the Consumer Price Index (CPI)—and it has remained significantly above its pre-pandemic trend in recent months.”

Neil Irwin at Axios explains how this report shows rent continues to hold the inflation rate up even as many parts of the country are finally reporting a decline in rent prices: “market rent data only encompasses people signing new leases. Many existing tenants saw no immediate change — perhaps because they had long-term leases in place, or landlords were reluctant to raise rent on existing tenants, or local laws constrained rent hikes,” Irwin writes

“But over time, those leases turn over, with more renters paying the higher market prices. That process is still underway, even though market rents have risen less in 2023 and 2024,” Irwin writes.

Because housing prices figure into the inflation rate slower than the other prices, Cotton estimates that over the next year, the inflation rate will remain unnaturally high. “This gap and the resulting growth in CPI shelter will lead to an additional growth in core (excluding food and energy) CPI and core PCE of 0.74 percentage point and 0.29 percentage point, respectively, over the next 12 months,” he writes.

In other words, because the Fed is so slow to incorporate fluctuations in rent into CPI data, housing prices stay higher for longer than the other prices the Fed uses to measure inflation. So the inflation rate will lag behind the reality of prices for most Americans by at least a year, even if rents continue to go down.

But those rents might not keep coming down. Irwin points out that “there could be a new surge in market rents due to under-supply” because “Construction of new multifamily housing has plunged below pre-pandemic levels in recent months as builders grapple with high interest rates.

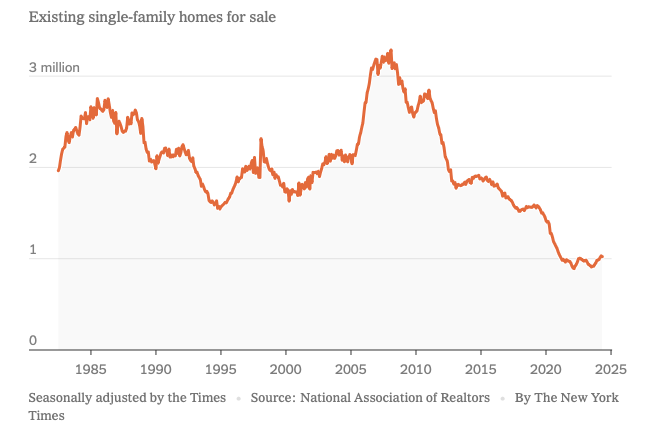

Ben Casselman wrote a piece for the New York Times that dimensionalizes what this tight housing market looks like for American homebuyers. Though the piece offers five charts, you really only need to see the first two. Here is the number of homes available to American homebuyers:

And here is the income needed to buy the median home for sale (the red line,) compared to the actual median household income for American families (the gray line):

When your supply line is dropping through the floor and your demand line is rising way above the means of working Americans, you have a huge problem. The solutions to this problem are pretty clear: We have to build lots of housing pretty much everywhere in the US, and the Federal Reserve needs to bring interest rates down so that the cost of mortgages drop.

Consumers Are Already Paying the Price of Climate Change

Almost all of the supply-chain stresses caused by global pandemic-era lockdowns have been repaired, rerouted, and rebuilt. But this summer we could be getting a reminder of how tenuous those supply chains really are. Peter Goodman writes that increasing unrest and wars near the Suez Canal is causing freighters to travel the long way around Africa, adding weeks to global shipping timetables. Additionally, workers at shipping centers around the world are striking or threatening to strike for higher wages and better working conditions.

For the Washington Post, Sarah Kaplan and Rachel Siegel write about consumers balking at the price of olive oil at Costco, which more than doubled last year. This price increase, though, has little to do with the broken supply chains of the pandemic era, or the greedflation that has held up grocery-store prices in the years since.

This time, the Post reports, the culprit is climate change. “In March, a study from scientists at the European Central Bank and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research found that rising temperatures could add as much as 1.2 percentage points to annual global inflation by 2035,” Kaplan and Siegel write.

“The effects are taking shape already: Drought in Europe is devastating olive harvests. Heavy rains and extreme heat in West Africa are causing cocoa plants to rot,” they explain. “Wildfires, floods and more frequent weather disasters are pushing insurance costs up, too.” One of the supply-chain stressors that Goodman wrote about in his report above, too, is directly caused by climate change: “a severe drought in Central America dropped water levels in the Panama Canal, forcing authorities to limit the number of ships passing through that crucial conduit for international trade.”

In the case of Costco’s olive oil price increases, we have to look back to the record-breaking heat wave that hit Europe early last year. “Scorching air sapped moisture from vegetation and soils, plunging much of the continent into drought and causing plants to wither and die,” Siegel and Kaplan write.

“Such high temperatures — which in some cases would have been “virtually impossible” without human-caused climate change, studies show — helped cut the region’s olive oil production to almost half of typical levels,” the Post notes. “Because the European Union produces more than 60 percent of the world’s olive oil, that shortage made itself felt at grocery stores around the planet — and among Costco fans on Reddit.”

Just as the economy grows better when we all do better, the whole world’s economy takes a hit when one region suffers. And when a product as popular as olive oil takes a climate-change inspired hit, consumers around the whole world pay the price. Meanwhile, the petroleum companies that have caused this climate change have reported record profits over the last few years. Let’s be clear: The higher prices that consumers pay due to climate change is the same pool of money as these profits the oil companies are making. They’re extracting value from our future and claiming it as billions of dollars of profits every quarter.

Real Workers, Fake Workers

When workers at Washington DC coffee shop chain Compass Coffee announced their intent to unionize back in May, they probably expected management to engage in some dirty tricks to discourage a union. As we’ve seen at union drives around the country, management always attempts anti-union strategies that stretch (and often break) the legal limit.

But those workers were shocked to learn that Compass Coffee allegedly hired 124 new employees in the last few months, primarily because those new employees apparently never worked a shift and seem to have only been hired to vote down the union. The Guardian’s Michael Sainato reports: “A coffee chain in the Washington DC area is accused of hiring dozens of friends of management, including other local food service executives and an Uber lobbyist, in an effort to defeat a union election scheduled for 16 July.”

Compass Coffee’s list of employees at a Georgetown location numbered 43 names including CEOs of other companies and the aforementioned Uber lobbyist, most of whom a supervisor of the store says she has never seen before. Sainato adds, “The union has also accused the company of manipulating worker schedules retroactively to try to make the new employees eligible to vote in the union election.”

If these accusations prove to be true, this is an unbelievably sloppy way to fix a union election, and it’s a reminder that business owners only try to discourage union votes like this one because unions are very good at growing the paychecks and benefits packages of workers.

Meanwhile, one of the highest-profile anti-union corporations of the last few years, Starbucks, appears to be moving toward finalizing a contract with workers at its 400 unionized stores. Noam Scheiber partially credits the National Labor Relations Board, which he writes “has been especially active and creative under President Biden. The board issued more than 100 complaints against Starbucks and went to court to reinstate workers it deemed to have been wrongly fired (though the Supreme Court just reined in this practice). The board even said it would begin ordering unions into existence if an employer’s labor-law violations affected the outcome of a union election.”

Thankfully, leaders are working hard in some parts of the country to grow the paychecks of non-union workers by raising the minimum wage. In April, California raised the minimum wage for fast-food workers by $4. Business owners dragged out the usual trickle-down threats, claiming that the increased wage would result in layoffs and restaurant closures.

For the Orange County Register, Jonathan Lansner takes a look at how the first month actually played out.

“Bosses at Southern California’s quick-serve restaurants added 4,800 workers in May to a new record high,” Lansner writes. “My trusty spreadsheet review of the Employment Development Department’s job stats found 362,000 workers at limited-service restaurants in Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties. That was up 4,800 for May and topped July 2023’s previous all-time high of 359,400.”

As you can see from Lansner’s chart, those numbers are up above pre-pandemic highs. When comparing this May’s numbers to “May hiring patterns in 2015-19,” Lansnser writes, “May 2024’s increase was nearly double the industry’s average of 2,760 hires during those five years.”

So restaurant owners did not mark the first full month of a $20 fast-food minimum wage by laying off workers wholesale. In fact, they delivered a record-breaking month of hiring. Those larger paychecks are already increasing consumer demand, which creates jobs. Yet again, the promised trickle-down apocalypse failed to materialize.

This Week in Middle Out

Last year, the Internal Revenue Service launched the Direct File service, which allowed Americans in 12 states to file their taxes directly with the IRS through an online portal for free. The program received more than a little pushback from Intuit, the producers of the TurboTax service that charges millions of Americans hundreds of dollars every year for access to their tax-filing software. The Center for American Progress reports that the IRS’s own customer satisfaction surveys show the Direct File program was a huge success with American taxpayers. Of those who used the service, 86 percent claimed “ the experience increased their trust in the IRS,” 90 percent characterized their experience as “excellent” or “above average,” and 80 percent said they would recommend the program to a friend.

In some states, workers receive their unemployment insurance payments in the form of prepaid cards. Unfortunately, those cards have been subject to junk fees and other restrictions that make it hard for people to actually access the UI payments. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau just announced that it had adopted new guidelines to protect unemployed workers from these junk fees and unnecessary restrictions.

“Nippon Steel’s bid to acquire U.S. Steel is in jeopardy over concerns about future job losses and plant closures,” writes the Washington Post. “The United Steelworkers has fought the $14.9 billion deal since its announcement last December — with the backing of President Biden. The president is counting on members’ votes in Pennsylvania and other battleground states to win in November.”

If the Biden Administration is looking to lower drug costs even more for consumers, the New York Times offers a great example of how giant pharmacy chains have killed competition and are driving up the cost of prescriptions for hundreds of millions of Americans. “They are called pharmacy benefit managers. And they are driving up drug costs for millions of people, employers and the government,” the Times writes. “The job of the P.B.M.s is to reduce drug costs. Instead, they frequently do the opposite. They steer patients toward pricier drugs, charge steep markups on what would otherwise be inexpensive medicines and extract billions of dollars in hidden fees.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Goldy and Paul talk this week with Chandra Childers, an economic analyst who published a report on the Southern economic development model, which promises deregulated business environments, a low-wage, non-unionized workforce, and significant tax breaks for businesses that choose to open in the south. That economic model, Childers proves, doesn’t deliver the promised economic growth—in fact, it has held the entire region back. Most importantly, though, Childers argues that the Southern economic development model is an extension of the racial oppression that thrived under slavery, which is why her report is titled “Rooted in Racism.”

Closing Thoughts

In the summary of her paper exploring the impacts of the Trump Administration’s so-called “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Beverly Moran concludes, “The TCJA is a poisoned tree planted in poisoned ground.” That’s obviously a bold statement, but every single paragraph of Moran’s 45-page report for the Roosevelt Institute points directly to that conclusion.

The “poisoned tree” of Trump’s tax law is a roughly $1.5 trillion giveaway to the wealthiest people and corporations in America, at the expense of the vast majority of working Americans. And the “poisoned ground” that tree was planted in is the existing tax code, which impoverishes Black Americans in particular and rewards wealthy homeowners at the expense of working renters in general.

“The TCJA’s reduction of the corporate tax rate and maintenance of the capital gains rate…increase wealth and income disparities while fueling racial injustice,” Moran writes. But again, those increases in the tax code only exacerbate inequality for everyone in the economy.

“Ending all itemized deductions would reduce the deficit by $2.5 trillion between 2023 and 2032,” Moran explains. “These monies could go to other social goods, such as deficit reduction, affordable housing, health care, and free college for all.”

I’d encourage you to read the whole report in all its wonky glory as it explains, piece by piece, exactly how Trump’s tax law specifically targets the wealth of Black Americans even as it rewards the wealth of the richest, overwhelmingly white, top one percent. Even wealthy Black American families didn’t benefit as much as their white counterparts: “Wealthy white households gained $52,400 per year from the TCJA, while wealthy black households received just $19,290,” Moran writes.

Moran knows exactly how Trump sold this plan—as the continuation of 40 years of trickle-down economics. “When the trickle-down theory first took off in the 1980s, the argument was that tax cuts lift all boats. After 50 years, no one can continue to make this claim—yet they still do,” she writes.

Those trickle-down lies were sold as ways to improve outcomes for everyone, but in reality they have only expanded inequalities that already existed in our society—inequalities between the wealthiest 1% and the bottom 90%, and inequalities between the way white families and black families accrue and retain their wealth. It’s only when we write a tax code that directly attacks those inequalities that we can begin to build an economy that grows for everyone—not just a privileged few.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach