Friends,

With the first presidential debate of the year coming up next week, people are starting to pay closer attention to the policies and proposals of the presidential candidates. Maybe that’s why Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump recently tried to take credit for President Biden’s $35 cap on insulin prices for Medicare patients, some of whom used to pay over $300 every month. Those lowered insulin prices are part of the reason why Biden consistently polls better than Trump for his handling of health care, although Trump’s repeated attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act with no replacement lined up to serve the 45 million Americans on an ACA plan also likely has something to do with his poor standing on health care.

In an effort to win over service-economy workers, Trump also proposed to exempt tips from federal taxes, arguing that it would give workers more money to spend. Actually, it would increase worker reliance on tips, essentially taking extractive low-wage employers off the hook and putting a bigger burden on customers—many of whom are already exhausted by tip culture—to provide wages for workers.

If Trump really wanted to improve outcomes for service-economy workers in a meaningful way, there’s already a successful policy in place to do just that: Raising the federal minimum wage to $15 or beyond. And he could also propose an end to the federal tipped minimum wage, which allows employers to pay servers and similar workers just $2.13 an hour, forcing them to make up the rest in tips. Study after study has shown that raising the wage creates jobs by increasing consumer demand, because when people who work in restaurants have enough money to afford eating in restaurants, that works out well for everyone.

Trump has also suggested lowering the corporate tax rate even further, despite abundant evidence that his previous tax plan only benefited the super-rich and that his additional proposed tax cuts would make the situation even more unequal in favor of big corporations and the wealthy few.

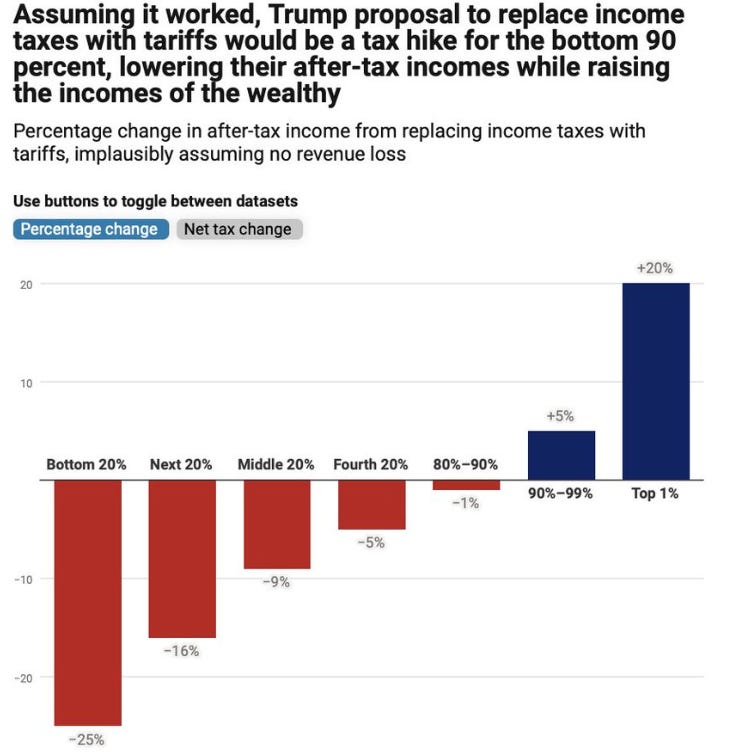

Earlier this year, Trump called for increasing tariffs by 10% across the board, which experts argue would raise prices for ordinary Americans by $1500 per year. Lately, though, Trump has gone even further, floating a proposal to eliminate the income tax altogether and replace it with increased tariffs, which would amount to huge price increases on most of the products that Americans buy while handing another massive tax cut to the wealthy. The Washington Post’s Catherine Rampell correctly argues that this tariff plan would create “a huge tax increase on the lower/middle income classes.”

The appeal with Trump’s proposed economic policies is that they’re big and they’re shocking and they get the attention of voters who are fed up with the status quo of rampant income inequality and are looking to blow the system up and start over. But if you scratch the surface on these allegedly populist economic proposals, you’ll see that they all improve outcomes for rich people and corporations, while increasing expenses and shrinking the paychecks of working Americans.

Much attention will be paid in the coming months to Trump’s threats to democracy and freedom—and for good reason. Trump has openly admitted that his potential second term would be about retribution and grievance. But not enough people are talking about the fact that Trump’s economic policies are simply trickle-down economics on steroids, thinly disguised as something sounding like populism.

It’s important for all of us who care about economic issues to get the word out to our social networks that the choice this November is a clear distinction between trickle-down policies that enrich the wealthy and middle-out policies that raise worker wages, lower their costs, and grow the economy.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

It’s Not an Inflation Problem, It’s a Housing Problem

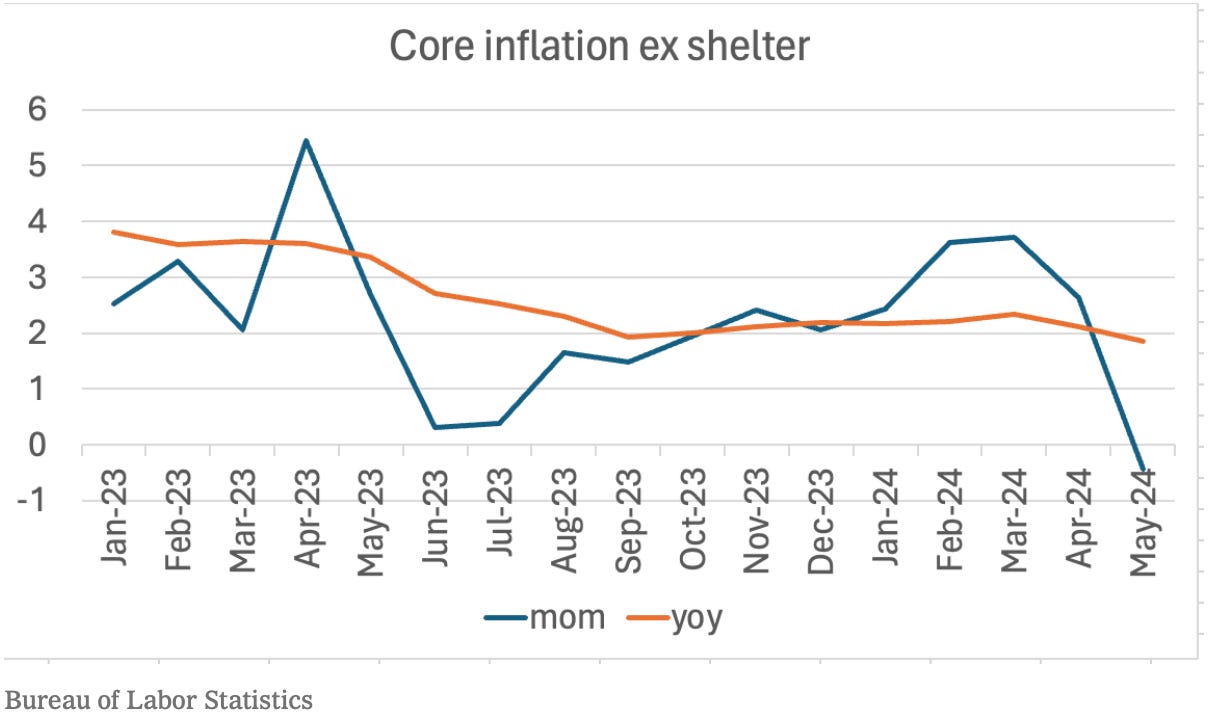

The economy is still reverberating with the aftershocks of the Federal Reserve’s recent decision to keep interest rates abnormally high, which is driving up the cost of housing for working Americans. Paul Krugman at the New York Times argues that if you take the cost of housing out of the inflation numbers, America’s inflation rate (both month-over-month, the blue line, and the orange year-over-year line) is at or near where it should be, which signifies that we have a housing price problem, not an inflation problem.

For the Wall Street Journal, Aaron Back argues that the Fed has other levers to pull in order to ensure that rates start to decline. “Following some weak economic data over the past few weeks—with the notable exception of Friday’s strong jobs report—the yield on U.S. 10-year Treasury notes moved from 4.7% in late April to 4.25% just before the Fed’s initial statement at 2 p.m. on Wednesday,” Back explains. “It ticked back up to 4.33% late Wednesday after the release of the Fed’s projections suggesting just one cut this year, then fell back to around 4.27% on Thursday morning after a weak producer-price reading.”

This matters because the treasury note rate “has a strong influence on loans made over the longer term, such as mortgages or loans to property developers for major projects. When it moves, it can have an immediate impact on conditions for borrowers in the real economy,” Back explains.

Back is arguing that the Federal Reserve is very slowly and subtly signaling that interest rates will decline, and that those signals will lower the cost of mortgages far before the Fed does actually lower interest rates. All this gossip and speculation makes for good fun for the economic media class, but the Fed’s subtle signals won’t pay the rent or quickly make mortgages more affordable for working Americans.

That uncertainty around house prices is a leading reason why retail sales barely ticked up at all last month, with just .1% growth over the month before. Courtenay Brown at Axios reports that “Sporting goods, book stores and other hobby shops were the strongest category for spending, where retail sales rose almost 3%,” but “furniture and home stores were among the weakest with sales declining by 1%,” and sales dropped by “0.8% at building supplier shops.”

The jobs report shows that wages are up and there’s more than one open job for every American looking for work. The only reason for sales to be dipping right now is because of a sense of uncertainty among Americans, particularly when it comes to housing costs. You’re not likely to splurge on building supplies, furniture, or home goods if you’re not sure where you’re going to be living in a year.

In a Strong Job Market, Some Are Still Falling Behind

For the New York Times, Noam Schieber writes about an ambitious plan to unionize Amazon’s warehouses. The Amazon Labor Union, which won an election at a Staten Island warehouse in 2022, has aligned itself with the Teamsters. “The Teamsters told the A.L.U. that they had allocated $8 million to support organizing at Amazon, according to Christian Smalls, the A.L.U. president, and that the larger union was prepared to tap its more than $300 million strike and defense fund to aid in the effort,” writes Schieber.

That alignment comes in an environment that is suddenly even more difficult for workers. Last week, Lauren Kaori Gurley reports, the Supreme Court ruled “to restrict the National Labor Relations Board’s authority to obtain relief for fired union activists, in a win for Starbucks that could deal a blow to labor organizing efforts.”

After Starbucks fired workers for inviting a TV news station into their store, the NLRB “agreed at the time with the workers’ claim that Starbucks had illegally fired them, and a court granted an injunction forcing Starbucks to rehire the workers.” The Supreme Court “found that the legal test the district court used to make that decision was too broad and inconsistent with other regional courts.”

While the decision was fairly narrow and centered around the particulars of this one case, it will undoubtedly create a chilling effect for future NLRB rulings. The best way to re-empower the NLRB is to pass the Protect the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which among other policies allows workers to work directly with the NLRB to establish the terms of union elections without employer involvement.

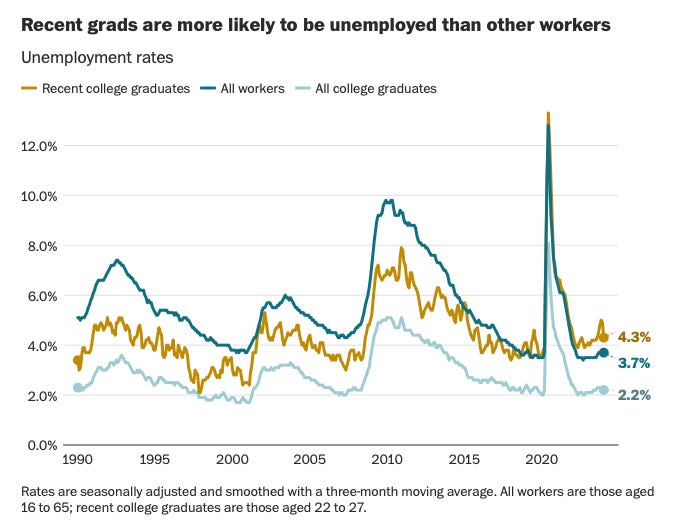

As we mentioned in the item above, workers still have a lot of individual bargaining power in the economy right now. But there’s one group of workers that have been left behind in the recent spate of job openings: New college graduates. Abha Bhattarai reports for the Washington Post: “Hiring is slowing, especially for recent graduates, with coveted white-collar employers pulling back on new postings. Just 13 percent of entry-level job seekers found work in the past six months.”

Firings and layoffs are down at the big, prestigious firms that many new graduates tend to target, meaning that those employers are focusing on retaining existing talent rather than building new talent pools. As a result, “Today’s recent graduates ages 22 to 27 have a higher unemployment rate — 4.7 percent, as of March — than the overall population,” she adds.

As we saw during the Great Recession, that slow start in the workforce creates a small but significant drag on young workers’ lifelong earnings.

Maybe that’s part of the reason why so many workers are going into business for themselves. “Since the Biden-Harris administration took office, 18.1 million new business applications have been filed, averaging 443,000 per month—over 90% faster than pre-pandemic rates,” reports Karen Stokes at the Milwaukee Courier. “The administration has already marked the first, second, and third strongest years for new business applications on record, and is on track for a fourth consecutive historic year.”

Notably, Black business ownership has more than doubled over those four years, women business ownership is at an all-time high, and Hispanic business ownership has increased by more than 40%.This is a striking reversal of shrinking entrepreneurship levels that have only gotten worse over the 40+ years of the trickle-down era—and a good sign for the labor market since small businesses traditionally create far more jobs than large corporations.

Building Guardrails to Keep Tech in Line

Tesla shareholders voted to affirm a $46 billion pay bonus for Elon Musk last week, after a legal challenge previously struck down the raise in court. It’s the largest payday for an American CEO in history, and the New York Times notes that the overwhelming shareholder support for the raise “was a setback for investors who had hoped it would send a message about the accountability of chief executives and the limits of executive pay.”

The pay bump is unlikely to deter Tesla’s Scandinavian workers, who have been fighting for the better part of a year to unionize the famously anti-union auto manufacturer. Payscale reports that the average pay for a Tesla employee is $26.25 per hour, with an average yearly bonus of $9000, meaning that the average Tesla worker would have to put in more than 1,750,000,000 hours of work (or roughly 200,000 years of working 24 hours every day) to take home the equivalent of Musk’s bonus.

Meanwhile, Crypto exchange Gemini has agreed to pay New York state a $50 million settlement after New York Attorney General Letitia James accused the exchange of defrauding its customers. Additionally, the business is now barred from “operating any crypto lending program” in New York State.

At the same time, Axios’s Brady Dale reports that the Securities Exchange Commission just announced it is finalizing regulations that “would allow institutional investors to take positions in the ether cryptocurrency, the coin of the Ethereum blockchain, just as they have in bitcoin since January.” Time will tell whether ether follows the same pattern of fraud that most other high-profile cryptocurrencies have fallen into.

In more heartening technology news, the Federal Trade Commission published a post warning tech companies to be truthful and transparent when discussing the capabilities of their artificial intelligence products. The post, which is one of the best-written government statements I’ve read in a long while, establishes some tips for AI merchants, including “Don’t misrepresent what these services are or can do,” “Don’t insert ads into a chat interface without clarifying that it’s paid content,” and “Don’t violate consumer privacy rights.”

The post served as a warning shot across the bow of tech firms who are busy creating a hype cycle around their AI products, and this week the FTC followed the warning with a more serious assertion. “We are not just closing our eyes and hoping self-regulation is going to protect the public,” Samuel Levine, the director of the FTC’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, told Axios. “We think if AI is going to be deployed successfully … we need to be active.”

This Week in Middle Out

Robert Kuttner explains why the apparent new head of the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission might be the best and most aggressive candidate yet in the administration’s ongoing fight against financial malfeasance. In her work heading up the the Troubled Asset Relief Program, “the little-known agency under [Christy] Goldsmith Romero’s leadership was superb at digging deep into bank scams to uncover episodes of fraud,” Kuttner explains. Sounds like exactly the kind of person we want in charge of overseeing banking regulations.

“High-end business partnerships like hedge funds and wealthy individuals such as real estate investors have inappropriately used labyrinthine structures to shield tens of billions of dollars from taxation, Treasury Department officials said Monday as they vowed to crack down on the practice,” writes the Washington Post’s Julie Zauzmer Weil. “They announced several steps to address a tax planning strategy known as basis shifting, in which complex business partnerships can move assets from one entity to another on paper for no reason other than to avoid taxes.”

Farah Stockman writes for the New York Times about Jennifer Harris, who she calls “The Queen Bee of Bidenomics,” particularly on the issues of trade and manufacturing. Harris, Stockman writes, “has been the quiet intellectual force behind the Biden administration’s economic policies, and she seemed key to understanding why both parties in Washington had walked away from free trade and neoliberalism — the belief that free markets will bring prosperity and democracy around the world.”

Dylan Tokar at the Wall Street Journal explains that a major practitioner of freight-forwarding, which “allow[s] customers in other countries to place orders for U.S. goods, which the companies then arrange to ship internationally,” has been placed under a rare three-year export ban. Critics argue that freight-forwarding companies like USGoBuy are undermining sensitive American corporate secrets by shipping products like rifle scopes that are not ordinarily exported to other nations.

The House of Representatives passed a bill that would eliminate hidden “junk” fees for hotels, airlines, and other travel services, “demanding that all mandatory fees are included in the advertised price.”

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

Political scientist Brian Judge joins Nick and Goldy to discuss the findings in his latest book, Democracy in Default: Finance and the Rise of Neoliberalism in America. In it, Judge argues that our understanding of how neoliberalism came to dominate American political thought is wrong: It wasn’t politicians shaping our economic policies, but rather wealthy financiers taking advantage of an economic downturn to instantiate a new economic regime that prioritizes the free market above common sense.

Closing Thoughts

For about a half-century, Rachel Cohen writes at Vox, Americans who need rental assistance have had to jump through a very elaborate set of hoops in order to stay housed.

“To get a voucher, a household first must prove eligibility. Then a public housing agency must issue the voucher subsidy to a landlord on the household’s behalf,” Cohen writes. “The landlord must then accept that voucher, the unit must pass an inspection, and the landlord must sign a contract with the public housing agency.”

The voucher system is inefficient, unpleasant, and needlessly complicated. And it’s that way by design: Trickle-downers have for decades worked tirelessly to make sure that accessing the social safety net is a herculean task that punishes anyone who needs it. Making government complicated, off-putting, and frustrating is a central tenet of trickle-down economics. The voucher system is such a hassle that many landlords simply refuse to bother with it, shrinking the pool of available housing to Americans who need assistance. (Some jurisdictions, including Washington state, already bar landlords from discriminating against potential tenants who use the voucher system, but most states don’t have even that most basic renter protection in place.)

It’s worth noting, too, that the voucher system rose to prominence after trickle-downers actively forced the federal government to stop building new public housing. It was a private-market neoliberal band-aid slapped onto a huge gap in the housing market created by trickle-down budget cuts.

But Cohen shares the exciting news that the age of the voucher bureaucracy might finally be at its end. Housing and Urban Development Deputy Secretary Brian McCabe “announced that his agency is soon planning to solicit public comment on the prospect of testing whether distributing cash directly to tenants might work better for renters, landlords, governments and even taxpayers.”

As we saw during the pandemic, the most efficient, effective way to get assistance to Americans who need it is through direct cash payments. Giving cash to Americans greatly reduced the poverty rate and improved the quality of life for millions of people. The enhanced unemployment program put in place during the pandemic allowed Americans to hold out for better-paying jobs, raising wages for everyone in the workforce. The Child Tax Credit nearly eliminated childhood poverty in the United States.

And vouchers are often presented as a way to prevent fraud, but the truth is that the infinitesimal population of criminals who seek to defraud the system will always find some way to hack programs to their own benefit. The goal should be to catch the fraudsters, not immediately treat anyone entering the system like a criminal.

“During the pandemic individuals seeking help under the $46.5 billion Emergency Rental Assistance Program could simply affirm, under penalty of perjury, details such as their income or address, rather than submitting official records,” Cohen explains. That threat of perjury is enough to ensure that the vast majority of people accessing benefits don’t exploit the system.

Most of those cash assistance programs faded away when pandemic relief funds dried up, but the effects were too positive to ignore. So now President Biden’s Department of Housing is investigating “whether landlords would be more willing to rent to low-income people if they could skip the government’s red tape, and whether there would be higher-quality housing available to renters using cash.“

Imagine that—allowing people to decide where they live, and supporting them directly. People would be able to choose the homes that work best for their families, ensuring better access to education for the children and more convenient access to work for the adults.

And let’s not forget that vouchers are a huge burden on administrators, too, with each new entry into the voucher system requiring nearly 14 hours of work to administer. “If cash proved effective and even helped save governments money, officials might be able to focus on providing more support services, producing new housing, and conducting research,” Cohen writes.

In other words, under a direct cash assistance system people needing assistance have more time and freedom to ensure that housing is right for them, and administrators have more time to make sure the system runs smoothly and efficiently. That sounds like a program that works better for everyone.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach