Friends,

During the trickle-down era stretching from the 1980s to 2020, workers either lost wages and benefits or, at best, stayed even. But over the past two years, American paychecks have grown at a rate that outstrips anything most of us have seen in our lifetimes. These gains have come due to a combination of unique pressures caused by both the pandemic—turning off the economy and turning it back on again meaningfully shook up the workforce—and President Biden’s signature middle-out investments in the working class.

Despite high prices caused by supply chain snags and runaway corporate greed, American workers have put those raises to work, creating jobs with their spending and powering one of the strongest national economic recoveries from the pandemic. It’s now clearer than ever that when workers have more money, that’s good news for everyone.

But Americans for Tax Fairness have discovered that another economic class has also done very well during the pandemic: Billionaires. Specifically, American billionaires have taken in some $1.7 trillion in wealth since the pandemic began in March, 2020. The 700 richest Americans absorbed an even larger share of our national wealth, hoarding more among themselves than the wealth possessed by hundreds of millions of American workers combined.

These two simultaneous gains tell a very interesting story about how the economy really works. First, the fact that the rich got richer at the same time that paychecks grew puts the lie to the trickle-down argument that the economy is a winner-take-all bloodbath in which raising wages for American workers kills economic growth among the so-called “job creators” in the top 1%. Paychecks rose last year at the same time that corporate profits and billionaire wealth dramatically spiked.

But since the trickle-down understanding of reality has it exactly backwards and working Americans, not the super-rich, are the real job creators, we can now see that worker wages have a lot more room to grow.

Let’s just flip the script as a thought experiment. If their wealth grew by a modest 5% during the pandemic, billionaires would still be unfathomably rich and their lives would not change at all. If that $1.7 trillion in wealth had gone into American paychecks over the course of the pandemic, rather than added to the already-swollen portfolios of a handful of billionaires, our economy would be even stronger for everyone right now—not just a few at the top.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

“This is what a recession looks like”

“Economic output in the U.S. posted the sharpest rise this month since April 2022, according to data firm S&P Global’s surveys of purchasing managers released Tuesday,” write the Wall Street Journal’s Paul Hannon and Harriet Torry. “The gain was led by service-providing businesses, which reported stronger demand for travel, dining out, and other leisure activities.”

While wealthy people keep claiming that a recession is imminent, to increasingly comedic effect…

…Joseph Politano at Apricitas Economics notes that “of the six indicators the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Recession Dating Committee looks at before declaring an official recession, only two (Industrial Production and Real Retail-Wholesale Sales) remain below their prior peak levels.” If anything, we’re seeing fewer warning signs of a recession than a few months ago.

Part of the reason those recession fears still feel real to most Americans, though, is that high prices have skewed their economic thinking. Even though more workers reported asking for and receiving raises in the last year, a lot of Americans—35%, higher than at any point since the Great Recession—reported being economically worse off than they were the year before. Price increases are slowing, but people are still noticing those high prices, and it’s hard to feel economically secure when your grocery bill is consistently, alarmingly high.

At the New York Times, Lydia DiPillis and Jeanna Smialek report that car prices have remained stubbornly high—to the point that car prices are helping hold the aggregate inflation number aloft.

But as with virtually every recent inflationary number, greed is a leading contributor: those high car prices are also driving near-record profits for car dealers, who are capitalizing on confusion in the market to pad their bottom lines.

Aside from a few lagging indicators like car sales, many prices are declining—including home prices, which the Wall Street Journal’s Nicole Friedman reports fell dramatically last month. “The national median existing-home price fell 1.7% in April from a year earlier to $388,800, the biggest year-over-year price decline since January 2012,” she writes. Total existing home sales fell 3.4% in April from the month before, with year-over-year sales declining by 23.3%.

But Axios notes, new home sales increased in April by 11.8% over the year before. Why such a discrepancy between new and existing homes? Axios points out that the people living in existing housing are likely trying to wait out very high mortgage rates before they have to buy a new home of their own, while home builders “appear more willing to cut prices in order to move their inventory of houses.” As a result, we’ve seen the price of new housing drop by nearly 12% this year while the price of existing homes has actually gone up by 6% for the year—even including April’s decrease of 1.7%. It’s weird out there.

So what’s going to happen to the economy next? Paul Krugman walks through several predictive scenarios in hopes of a so-called “soft landing” that would bring prices down while also keeping people employed. He predicts some more turbulence ahead for prices, and a slightly weaker job market—in other words, the same kind of choppy waters we’ve been seeing for a while now. But he argues that despite all that, “the overall story of the postpandemic economy will be one of remarkable resilience.” If so, that resilience will be entirely thanks to the American worker.

Against “Work Requirements”

As Republican lawmakers continue to hold the economy hostage with a manufactured debt ceiling crisis, we’re one week away from the June 1st deadline. Somewhere around that date—give or take a week, maybe?—the United States won’t be able to pay its bills. But Ben Casselman and Lydia DiPillis at the New York Times report that even if Republicans were to relent immediately, serious damage might already be done to the US economy.

“The long uncertainty could drive up borrowing costs and further destabilize already shaky financial markets,” they write. “It could lead to a pullback in investment and hiring by businesses when the U.S. economy is already facing elevated risks of a recession, and hamstring the financing of public works projects.”

One of the major Republican spending-cut demands is the installation of so-called “work requirements” on food stamps and other investments in poor Americans. This is an old neoliberal talking point dusted off for the modern era—the Clinton administration incorporated it into its welfare reform, with dire results. But these requirements make even less sense now than they did in the 1980s and 1990s.

The only thing that work requirements do is make it harder to access antipoverty programs. While you might see numbers of people enrolled on TANF programs decline if you make it harder to access the programs, the fact is that the parents and children who disappear from TANF rolls aren’t pulled out poverty—they’re just forced to find other ways to get assistance, or they fall even further out of the economy, which then takes money out of the economy.

Worse yet, many people on TANF and other assistance programs are already working full-time jobs, which is as stark an indictment of predatory low-wage employers as I can imagine. A good job is supposed to get you out of poverty, not allow you to access anti-poverty programs.

We just saw during the pandemic that the best way to provide assistance to Americans—the single best anti-poverty program our leaders can embrace–is to get cash to people who need it. After programs like the Child Tax Credit went out to millions of Americans, our unemployment numbers didn’t skyrocket. Instead, people invested that money into their communities, or used it to help them find better employment elsewhere. This work requirement “debate” is just as dumb and regressive as the manufactured debt ceiling “crisis” itself. How many times do we have to keep having the same unproductive arguments about investments in impoverished Americans when we already know what actually works?

Corporate Greed Comes in Many Flavors

The New York Times reports on the trend of corporations which made hundreds of billions of dollars by appealing to the values of urban progressives suddenly turning heel by combating unions. Noam Scheiber recounts Apple firing several pro-union employees at an Apple Store in Kansas City. “A pattern of similar worker accusations — and corporate denials — has arisen at Starbucks, Trader Joe’s and REI as retail workers have sought to form unions in the past two years,” Scheiber writes.

“Initially, the employers countered the organizing campaigns with criticism of unions and other means of dissuasion. At Starbucks, there were staffing and management changes at the local level, and top executives were dispatched,” he continues. “But workers say that in each case, after unionization efforts succeeded at one or two stores, the companies became more aggressive.”

We’re drawn to these stories because the hypocrisy of these employers is breathtaking—they claim to respect their workers and back human rights. But the minute some lower-wage employees take action to fight for their own interests, these companies exhibit the same greedy anti-worker tactics that you’d expect from a vulture-capital private equity firm.

And if the most prestigious corporations in America are behaving like this, imagine what the bottom-feeders are up to. Maureen Tkacik writes for The American Prospect about a man who bought a community hospital in rural California with the plan to “immediately sell the hospital’s underlying real estate to an Alabama real estate investment trust named Medical Properties Trust (MPT), for $55 million, and lease it back for millions of dollars a year in rent and interest payments.”

The hospital was profitable before the sale, but not millions-of-dollars-a-year profitable. Within months, the hospital’s owner was slashing costs, cutting benefits, and throwing the hospital into bankruptcy with tens of millions of dollars in debt. Given the speed of the collapse of this whole house of cards, it seems apparent that the plan was never to run a profitable hospital—it was to profit from the real estate through complex machinations.

Tkacik explains that the hospital was fleeced through an investment structure called real estate investment trusts, in which organizations “receive tremendous tax advantages in exchange for agreeing to adopt rigid, low-overhead structures and pay out 90 percent of the profits to investors, who in turn are allowed to write off a portion of those dividends as business expenses.”

It’s basically another vampire technique in which a small-but-healthy asset—the hospital in this case, but also declining retail firm Mervyn’s, a nursing home chain, and restaurant chain Friendly’s—is basically thrown in between a rapacious buyer and a sharklike financial firm. The ensuing chaos gets both the buyer and the seller rich, but it drains the original asset completely dry and then loads its corpse down with millions of dollars in debt. Is this legal? Probably not, Tkacik guesses, but all the lawsuits surrounding these cases are moving so slowly that nobody has faced any meaningful repercussions.

This kind of behavior is exactly what government is for—to support workers when they advocate for themselves, and to establish regulations that stop people from targeting businesses in an effort to make tens of millions of dollars on the misery of others. Just yesterday Minnesota Governor Tim Walz signed the Warehouse Worker Protection Act into law, which, as the Nation explains, “requires employers to provide warehouse workers with written information about all quotas and performance standards they are subject to, in addition to how those quotas and standards are determined.”

The law requires employers like Amazon to supply that information in the workers’ native language and it “also stipulates that employers cannot fire or take disciplinary action against a worker who fails to meet a quota that wasn’t disclosed, disarming one of the primary excuses Amazon may use to punish or fire workers who seek better conditions or organize.”

Making Middle Out Real

“Thanks to federal and state industrial-policy initiatives, upstate New York is emerging as a center of advanced semiconductor and wind-turbine manufacturing, and much of it will be unionized,” Robert Kuttner writes at the American Prospect. He outlines how wind farms and semiconductor factories are bringing thousands of jobs back to a region that has long been economically depressed. And these jobs aren’t being created due to the gentle caress of the free market’s invisible hand—they’re coming to New York because state and federal leaders crafted policy to encourage big investments that create good jobs.

This is the result of good policy, and there are always ways to improve policy even more. The Roosevelt Institute released a great paper yesterday explaining how government can speed up this process by expediting permitting processes and fostering the growth of green-energy companies without sacrificing environmental protections. And the Washington Center on Equitable Growth explains how government policy wonks can adjust our federal cost-benefit analysis structure—which shapes the policies that foster growth like these semiconductor plants and wind farms—to more directly address economic inequalities that affect people due to factors like race, gender, and income.

The New York Times also notices the semiconductor boom happening in rural regions. “More than 50 new facility projects have been announced since the CHIPS Act was introduced, and private companies have pledged more than $210 billion in investments,” writes Madeleine Ngo, who then asks, will these factories be able to find enough workers to fill all the new jobs?

Respectfully, nobody asked that question of all the oil companies that set up in North Dakota during the fracking boom. And the reason why is that the oil companies offered enough money that plenty of workers were willing to uproot their lives. Semiconductor manufacturers have to be willing to attract the high-quality workforce that they need, and that means investing in workers. But the beautiful thing about investing in workers is that the workers then create the kind of community that attracts more workers with their spending—their dollars fund the new restaurants, leisure centers, and community attractions that make a place worth living.

And anyway, one of America’s greatest economic strengths is that it welcomes people from around the world who want to work. The Wall Street Journal reports that despite Trump-era slowdowns, immigrants now make up an all-time high share of the American workforce.

“People born outside the U.S. made up 18.1% of the overall labor force, up from 17.4% the prior year and the highest level in data back to 1996, the Labor Department said in its annual report on foreign-born workers,” write Gabriel T. Rubin and Rosie Ettingham. “The number of immigrants in the labor force—those working or actively looking for jobs—rose by 1.8 million, or 6.3%, to 29.8 million in 2022.”

Those workers from other countries aren’t “taking jobs.” They’re working, and spending money, and paying taxes. Possibly the greatest thing that Congress could do to improve America’s economic output right now would be to finally pass some sort of meaningful immigration reform, making it easier for people to join our workforce. The happy truth is that there’s always enough work to go around.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

This week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics features a great interview with economist Michael Reich about that breakthrough minimum wage study we’ve been talking about for the last couple of weeks. Reich explains the groundbreaking methodology that discovered raising the minimum wage by a large amount creates jobs and grows wealth in rural counties.

Closing Thoughts

There is no indicator of future economic success greater than the possession of generational wealth. Children born into middle-class families have a small but significant chance of falling out of the middle class as adults, but children of privilege rarely wind up living paycheck to paycheck. The fact is that once great wealth successfully passes from one generation to the next, it tends to be protected from attrition. That is to say, it usually grows at an ever-faster rate, protected from taxes and ensconced in elite investments that aren’t available to ordinary working Americans.

For the New York Times, Talmon Joseph Smith and graphic designer Karl Russell identify one of the biggest wealth transfers in American history—one that’s unfolding in slow motion around us every day: As the Baby Boomer generation dies, they are passing on their unprecedented stores of wealth—$78.3 trillion, nearly as much as every other living American generation combined—to their heirs.

“The wealthiest 10 percent of households will be giving and receiving a majority of the riches,” Smith writes. “Within that range, the top 1 percent — which holds about as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent, and is predominantly white — will dictate the broadest share of the money flow.” The bottom half of Boomer households will divert less than 10 percent of that generational wealth to their children.

How did Boomers take in so much more wealth? The answer is mostly real estate—they bought homes and land when prices were low, and now prices are astronomically high. Other financial investments—including many stocks—were also affordable thirty years ago but beyond the reach of working Americans today.

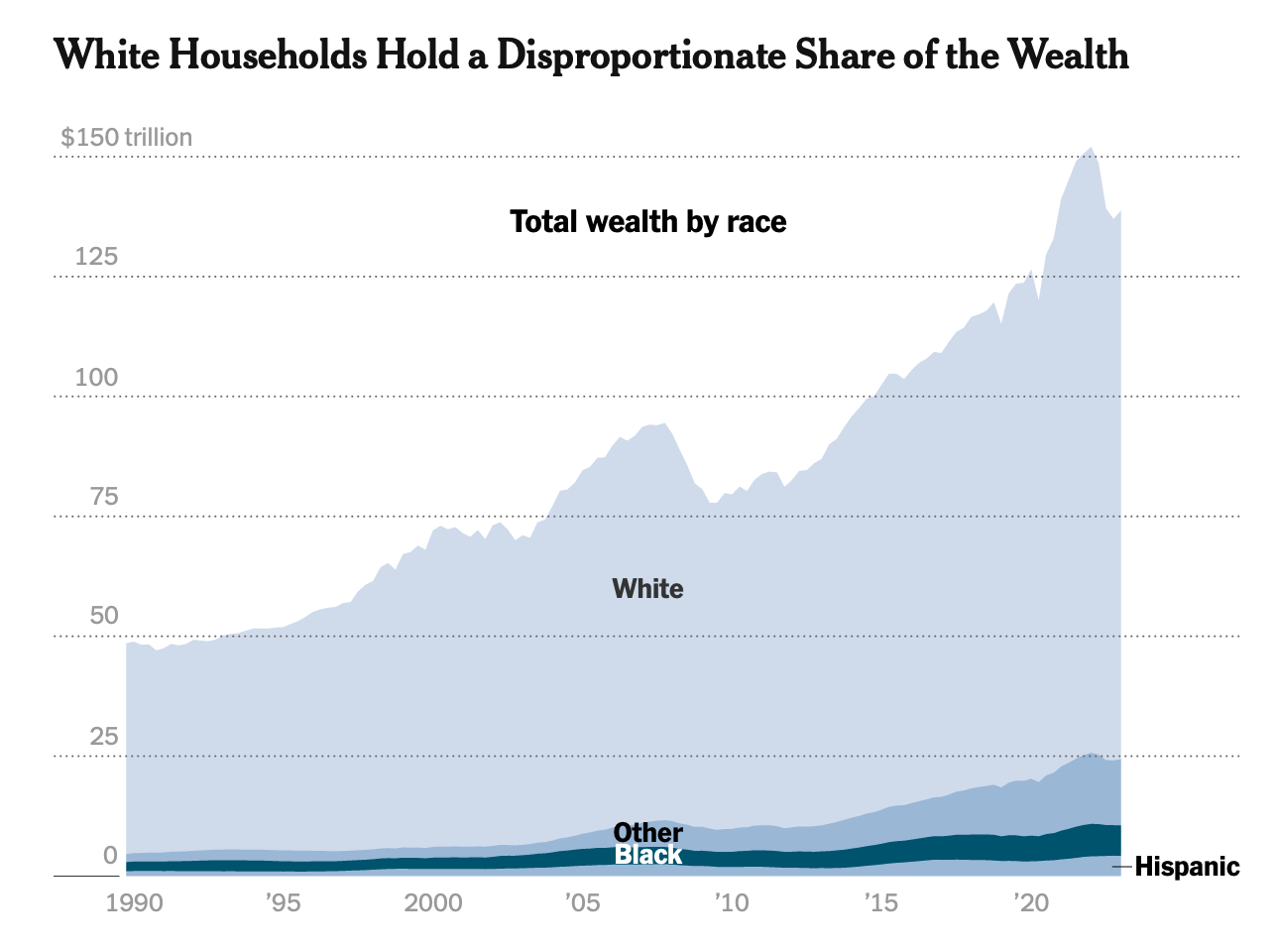

The problem with this wealth passing from one generation to the next is that it perpetuates many of the institutional tragedies that were in place when Boomers began accruing wealth. It was harder for Black families to purchase homes due to openly aggressive racist systems, for example. A white family passing a home down across generations has a huge head start in building economic stability and establishing wealth compared to a Black family of the same educational background. That’s how you get wealth inequality this staggering:

In the coming years, just 1.5% of the wealthiest Boomer households will transfer at least $36 trillion on to their heirs. “The scale of the transfer is made possible in part by the U.S. tax code,” Smith writes. “Individuals can transmit up to $12.9 million to heirs, during life or at death, without federal estate tax (and $26 million for married couples).”

Trickle-down politicians did such a good job of rebranding the inheritance tax as a loathesome “death tax” over the last 40 years that the passage of intergenerational wealth has become instantiated into the tax code. But it’s time to reinvestigate the amount of wealth that can be passed from one generation to the next. Every parent wants to leave their children with a legacy. But when super-rich Americans pass millions (and even billions) of dollars from one generation to the next, the mistakes and tragedies of the past are passed along with them.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach