Friends,

It would be hard for anyone to argue that the American tech sector is in excellent shape right now. In addition to the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, Big Tech companies have enacted wave after wave of high-profile layoffs, with thousands of workers unceremoniously dumped (often via emails using very questionable language) every few weeks. If you look closer at the numbers behind those layoffs, you’ll notice that the tech industry isn’t exactly in danger of going extinct. Microsoft laid off thousands of workers after its profits fell by 12%, for instance, but the company still made $16.43 billion in profits in the last quarter of 2022. And while Amazon has laid off 27,000 employees this year, that’s a relatively small sliver of the 381,500 employees the company added during the first two years of the pandemic.

But still, after nearly two decades of unstoppable growth, the tech sector is currently in chaos. Stock prices and profits that always seemed to float ever-higher since the first dotcom bubble burst in the early 2000s are now suddenly subject to the laws of gravity. Because of that 20 years of dominance, tech’s sudden moment of weakness has left people feeling skittish about the economy. Will those layoffs and bank failures continue to spread throughout the rest of the American economy?

I wanted to call your attention to some analysis from Bloomberg’s Joe Weisenthal that was buried at the bottom of yesterday’s Five Things You Need to Know to Start Your Day newsletter, because it rings true, and not enough economics reporters are saying it: “What defines this economic expansion is that it's bottom up, not trickle down. It's consumer strength, particularly in the middle and lower levels that keeps it going,” Weisenthal writes.

To support that argument, Weisenthal cites an observation about the continued economic success of Carnival Cruise Lines from Samuel Rines, managing director of the research intelligence advisory platform Corbu LLC: “While it is popular to make broad statements about the death of the consumer, justifying it against what companies are saying is problematic,” Rines writes.

“Carnival is not the most expensive cruise line, and this is not a signal of the `luxury consumer.’ It is a signal of Middle American spending. Middle America does not care about SVB or [Silvergate Bank] or [First Republic Bank],” Rimes continues. “Middle America sees higher wages and job postings everywhere. Which leads to a confidence in being able to book that cruise.”

The broader point that Weisenthal is making needs to be shared more widely: Unlike the economic recovery from the Great Recession, which was near-immediate for Big Tech companies and the financial sector and glacial for ordinary Americans, our economic recovery from the pandemic and lockdowns has instead centered on preserving and strengthening the middle class.

Still, we can’t ignore the fact that even though inflation has been on a steady decline, prices are still too high. The Washington Post recently published an interactive article illustrating why inflation has caused many middle-class Americans to feel so pessimistic about the health of the economy. If prices continue to fall, those same Americans will likely begin to feel the economic power that they’ve gained over the last two years.

This recovery has been roundly better for everyone than the Great Recession, because the spending power of working Americans circulates throughout the economy, creating jobs and powering businesses. Big Tech might be feeling a bit of a pinch right now, but the economy as a whole is strong because the American economy isn’t powered by Big Tech. It’s powered by people.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

What Happens After You Break the Bank?

This week, the U.S. government sold the remains of Silicon Valley Bank to First Citizens Bank. The collapse is estimated to have cost the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation 20 billion dollars, which the Washington Post’s Aaron Gregg and Bryan Pietsch note is “the most expensive bank failure in U.S. history.” (We should note that FDIC funds are raised from fees charged to banks, which means that $20 billion isn’t taxpayer-funded.)

The sale of SVB to First Citizens was finalized under the agreement that the FDIC and First Citizens “will share in any loan losses as part of the transaction. About $90 billion in securities and other assets will remain under FDIC control, including First Citizens stock, which the regulator said has a potential value of up to $500 million,” the Post notes. With the addition of SVB’s remaining assets, First Citizens will fall just under the $250 billion “mid-sized bank” threshold that, if crossed, would have introduced the bank to more regulatory scrutiny.

The sale marks the end of one phase of the banking crisis, and a step back from the imminent danger that SVB’s collapse posed to the rest of the financial industry. If you’ve been holding your breath waiting to see if SVB would lead the rest of the banking system off the cliff, you can exhale now—but of course, our leaders have much to do in order to stop the next SVB collapse before it starts.

Federal Reserve officials appeared before Congress to answer questions about how the Fed allowed the SVB collapse to happen in the first place. “Democrats pressed the officials on whether gaps in regulation had allowed problems in the banking system to build after rollbacks under the Trump administration,” reports the New York Times’s Jeanna Smialek. “Republicans, by contrast, blasted Fed supervisors for either missing obvious risks or not addressing them effectively.”

The Times’s Alan Rappeport rounds up all the finger-pointing happening in and around the Fed’s testimony. Regulators said SVB failed because it was managed ineptly. Most everyone agreed that SVB’s executives needed to be fined or otherwise face consequences for their mismanagement. But the Fed also called for more regulatory power, and leaders argued that the Fed was asleep at the wheel.

For what it’s worth, David Dayen at The American Prospect definitely subscribes to the “asleep-at-the-wheel” side of the argument, making a great case that because SVB wasn’t afraid of the Fed’s regulatory power, that power might as well not exist. “The entire regulatory architecture set up after the 2008 crisis has now been exposed as insufficient, given the deregulatory pummeling it has taken in the intervening years,” Dayen argues, adding, “the bank sector has been revealed as incredibly fragile.”

And the Biden Administration is preparing a set of rules that will “try to reestablish rules for banks with between $100 billion and $250 billion that were deregulated by Congress and the Fed during the Trump administration,” reports the Washington Post. Those rules are currently being hotly debated within the administration, and we’ll learn more about them in weeks to come. Other outlets are making recommendations of their own for sweeping banking reform, including some policies proposed by Peter Coy in The New York Times. The most interesting of Coy’s policies to me involves pulling the regulation of banks away from the three or four separate agencies that currently share responsibilities, giving all of that regulatory power to the FDIC, and really giving the newly empowered FDIC’s regulations some teeth, because we already learned that having a number of weak regulators sending sternly worded letters did absolutely nothing to curb SVB’s collapse.

Real Estate Prices Continue to Fall

Nicole Friedman at the Wall Street Journal reports that “The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller National Home Price Index, which measures home prices across the nation, fell 0.2% in January compared with December on a seasonally adjusted basis.” She adds, “Prices have fallen for seven straight months, the longest streak of declines since 2012.”

These prices are falling in large part because mortgage rates have skyrocketed with the Fed’s recent spate of interest-rate hikes, driving consumer demand downward. So while the listed price of any given home may be a bit lower than it has been in recent years, mortgage rates are driving the actual price that you’d pay over the life of the loan way up.

One of the most underrated stories of the week comes from Jeff Stein at the Washington Post, who warns that commercial real estate prices have fallen drastically since the pandemic began and remote work has increased. That decreased demand in the $20 trillion commercial real estate market has some experts warning of a crash in the market sometime in the next two years.

A lot of the debt for commercial real estate is tied up in midsized banks like SVB which profited greatly from the commercial real estate boom of the 2010s. At least 400 mid- and large-sized banks are loaded down with commercial real estate loans, Stein found, and if commercial real estate does shrink in value by as much as 30% over the next few years, as some of the direst predictions claim, that could spell disaster.

“So far, developers and the banks that lend to them haven’t been badly affected, because commercial real estate leases tend to span several years, unlike the one-year terms for most residential units,” Stein writes. “But millions of these leases are going to expire over the next two years, potentially setting off a domino effect that could rattle the U.S. financial system.”

Stein isn’t all-in on the doomsaying, though. He notes that “Many midsize banks, seeing the potential danger last year, began diversifying their portfolios and stockpiling safe assets to protect against a downturn in commercial real estate.” But any regulations that our leaders are considering to avoid the next SVB should take this potential crash into account, and work to avoid the next crisis before it really begins.

This Week in Regulations

One of the big problems with discussing regulations in the media is the fact that when regulators effectively regulate a system, it doesn’t make headlines. A well-regulated system, by definition, isn’t news. It’s only when regulations fail, or when an unregulated system collapses, that we tend to notice.

So let’s take note of this New York Times story about regulators who are working mightily to try to avoid a potential crypto crisis: “Federal regulators sued Binance, the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchange, and two of its senior executives on Monday, alleging that in wooing business from American investors, they had chosen to ‘knowingly disregard’ laws governing certain U.S. financial markets.” Crypto is a woefully under-regulated market, so it’s good to see the government stepping in and taking action to enforce the regulations that do exist, in order to avert the next headline-dominating crisis.

Sometimes the regulatory state doesn’t work as it should. David Dayen reports that the Department of Health and Human Services rejected a petition to use government power to lower the price of “a cancer drug called Xtandi (enzalutamide), which lists at an average wholesale price in the U.S. of $188,900 per year. Even with insurance, co-pays range as high as $10,000 or more”—a price that is anywhere from three to six times as expensive as any other nation in the world. The National Institutes of Health rejected the petition on the grounds that the drug is “widely available to the public on the market,” which is a truly ghoulish thing to tell cancer patients who now have to muster nearly a thousand dollars a month in order to get life-saving treatment.

Meanwhile, a ProPublica report found that captains of industry are gliding underneath existing regulations. This All Things Considered segment offers a good summary of the ProPublica report, which alleges that corporate executives are making millions of dollars by trading competitors’ stocks in perfectly timed deals that seem to suggest insider knowledge might be at work.

A Gulf of Mexico oil executive invested in one partner company the day before it announced good news about some of its wells. A paper-industry executive made a 37% return in less than a week by buying shares of a competitor just before it was acquired by another company. And a toy magnate traded hundreds of millions of dollars in stock and options of his main rival, conducting transactions on at least 295 days. He made an 11% return over a recent five-year period, even as the rival’s shares fell by 57%.

ProPublica explains that when it comes to insider trading, regulators tend to focus on corporate employees utilizing specialized knowledge of their own companies to take advantage of the market. But corporate executives have largely gone unpunished for taking advantage of information they possess about their competitors. All in all, the piece makes a great case that our leaders should make it illegal for executives to trade the shares of their competitors.

But regulation isn’t just about penalizing bad actors. It’s also about encouraging positive behavior. William Kuttner points out the Department of Energy’s conditions for companies applying for the $7 billion in energy programs established under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act. Companies that want money must submit a plan which includes “four elements: Community, labor, and stakeholder engagement; a diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility plan; support for the administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which applies 40 percent of funds to historically marginalized groups; and explicit plans to invest in the workforce and promote workers’ rights.” Kutttner continues, “the Energy Department has made clear that one easy way to meet the labor goal is to have a union.”

This Changing Face of Labor Inequality

Speaking of unions, the Los Angeles Unified School District strike that I wrote about last week was an unqualified success. “Local 99 of the Service Employees International Union, which represents support workers in the district, said that Los Angeles Unified, the second-largest school district in the nation, had met its key demands, including a 30 percent pay increase,” reports the New York Times.

This victory will undoubtedly be a positive sign for other American workers who are fighting to unionize, including at Starbucks stores around the country. Former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz testified before Congress yesterday, and The New Republic notes that he may have accidentally admitted that Starbucks violated labor law by not extending benefits to unionized workers. Schultz, who is a billionaire, hilariously threw a fit after being called a billionaire during the hearing: “I came from nothing. Yes, I have billions of dollars. I earned it. No one gave it to me,” Schultz testified. Apparently, he doesn’t see the obvious connection between his billions of dollars and the low wages that unionized Starbucks employees are protesting.

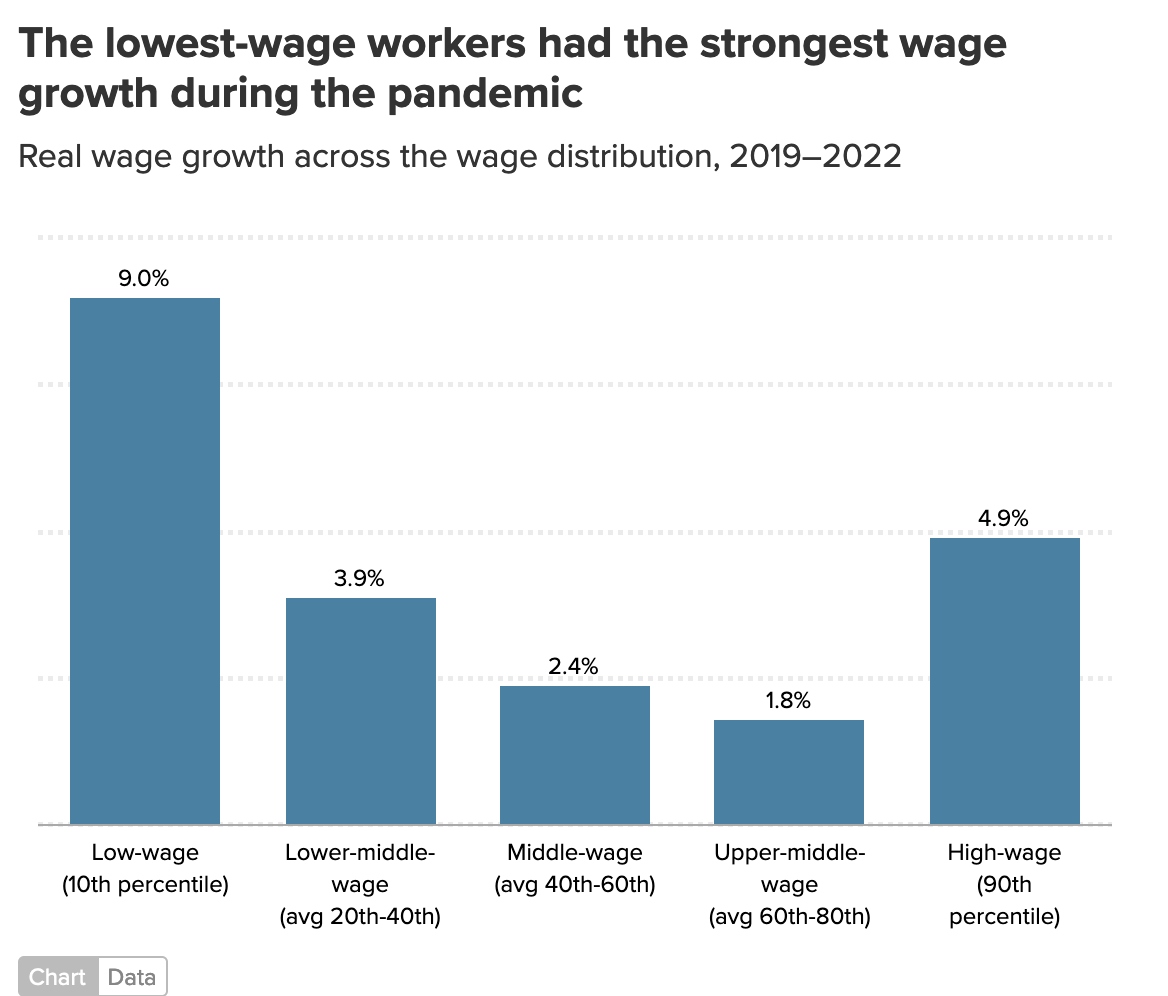

Those Starbucks workers are partially empowered by a wave of wage increases benefitting workers at the lower end of the wage spectrum. The Economic Policy Institute has dimensionalized the gains that low-wage American workers made during the pandemic. Take a look at this chart, which shows that low-wage workers nearly doubled the gains made by the highest-wage workers between 2019 and 2022:

But to be clear, workers in the lowest quintile have a lot more ground to make up than any of the other quintiles. Here you can see how tiny their wage gains have been over the last 45 years:

Work in America is just as rife with inequality as the accrual of wealth. And it’s easy to see the divide in this chart accompanying Gwynn Guilford’s Wall Street Journal article about workers who have been allowed to work from home over the past year:

In general, the lower down this chart you go, the lower the wages are. High-wage workers don't just enjoy higher pay and better benefits—they also have more freedom to work from home at least some of the time.

Obviously, not every job can be accomplished remotely. Service, construction, driving, and warehouse jobs all require workers to be in-person. But at a point in American history when the majority of high-paid office and information economy workers are allowed to skip out of commuting at least part of the week, low-wage workers should be compensated even more for their time and energy.

Shorting the Fed

We’ve spent a lot of time talking about the Federal Reserve in this newsletter over the last couple of weeks, so rather than diving deep into the same subject again, I wanted to close the news portion by briefly spotlighting a couple of interesting developments:

Jim Tankersley at the New York Times points out that Fed Chair Jerome Powell aggressively pushed back against Republican assertions that government spending is a main driver of inflation. Trickle-downers have long used inflation as a bogeyman to combat spending proposals, and Powell’s riposte is a useful counterpoint to those claims.

Also at the Times, Jeff Sommer questions why the Fed is so determined to get inflation down to its target of 2%. He argues that the 2-percent inflation sweet spot is based on an arbitrary figure set by New Zealand in the late 1980s. Perhaps, Sommer argues, inflation stability is a better goal than a fixed percentage. “Only when those [price] increases feel out of control — as they have over the last year or two, and as they did in the 1970s and early 1980s — has inflation mattered to me, as a citizen and as a consumer,” Sommer writes. He argues that any number below 4% feels reasonable, and so perhaps the goal shouldn’t be to hit a target number but to keep inflation from rising above a maximum.

Real-Time Economic Analysis

Civic Ventures provides regular commentary on our content channels, including analysis of the trickle-down policies that have dramatically expanded inequality over the last 40 years, and explanations of policies that will build a stronger and more inclusive economy. Every week I provide a roundup of some of our work here, but you can also subscribe to our podcast, Pitchfork Economics; sign up for the email list of our political action allies at Civic Action; subscribe to our Medium publication, Civic Skunk Works; and follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway join Nick and Goldy on this week’s episode of Pitchfork Economics to discuss their new book The Big Myth, which digs into the history of how free-market economics became widely accepted. The concept that government is slow and inefficient while free markets are the wisest, most efficient way to distribute resources hasn’t always been a widespread belief among the American people. In fact, it took a lot of work (including “the largest peacetime propaganda campaign in US history”) to sell that myth.

Closing Thoughts

I’d like to close with a little news from my home state of Washington. Last Friday, the Washington State Supreme Court decided overwhelmingly in favor of a tax on the extraordinary capital gains profits of the super-rich that was passed by the state legislature last year. The tax will only touch a few thousand Washingtonians per year—those who are wealthy enough to draw over a quarter-million dollars in annual profits from the sale of stocks—and the revenue derived from the tax will be invested into childcare and public education.

Soon after the court announced their decision, a firm with offices in Washington State, Fisher Investments, announced that they were moving their firm’s headquarters from Washington to Texas. This is the kind of attention-grabbing headline that wealthy people love to use as a scare tactic once taxes are announced, but as the Oregonian noted, “Ken Fisher, the billionaire who started the firm, has said in the past that headquarters designations are irrelevant. Fisher already lives in Dallas, according to his social media profiles.”

So a guy who already lives in Texas and previously said there is no significance to official headquarters locations announces he's moving to Texas and changing his headquarters location. This is not news. But Fisher’s announcement worked as intended, kicking off a flurry of concern trolling on social media and in the conservative media. Will all the rich people leave Washington State?

Taylor Soper at Washington media outlet Geekwire examined the threats, and I wanted to highlight his coverage as a model for how all reporters should cover economic issues. Soper repeats some of the threats made by ridiculously wealthy people like Fisher, but he then looks at the numbers. Do rich people actually move to avoid paying taxes? According to a vast body of research, no.

Soper cites a “2016 study examining 45 million tax records [which] found that most wealthy people don’t move to avoid paying high taxes.” He interviews Cornell University’s Cristobal Young, who also cited three other studies across states including Washington, California, and New Jersey that all found taxes to be “a minor factor in the migration of the rich.”

And Soper talks with University of Washington Technology History Professor Margaret O’Mara, who argues that “The history of Silicon Valley suggests that other regional advantages outweigh tax laws for most people and firms”—in other words, wealthy people and their businesses might clamor about leaving over taxes, but they tend to stay in locations with plenty of amenities and a diverse hiring pool full of educated, talented workers.

Wealthy people use scare tactics like Fisher’s headquarters swap to frighten working Americans into opposing taxes on the wealthy. And anecdotally, possibly one or two wealthy people will leave Washington state—though you’d have to be a sociopath to uproot your entire life and move solely to avoid paying $7000 taxes on a $350,000 annual profit from the sale of stocks, as would be the case with Washington’s capital gains tax. But the vast majority of people will stop grumbling and pay the tax.

For the article, Soper also talked with Civic Ventures founder Nick Hanauer, and I wanted to include his full statement here as a last word on the matter, because it dismantles the whole argument in a way that is quintessentially Nick:

For years Washington has had the most upside-down tax code in the nation, where the lowest-income families in our state pay up to 18 percent of their income in taxes and the wealthiest tenth of a percent like me pay next-to-nothing. On average I’ve probably paid less than 1 percent of my income in state taxes. This tax on capital gains profits will move that needle slightly, but I’ll still likely only be paying 3 percent or less. It is unfathomable to me that any of my rich pals would look at those numbers and think that’s too much for them to contribute to our schools, and frankly I don’t know how anyone in my position can live with not doing their part and pitching in.

Businesses flock to Washington because we invest in our people, our infrastructure, our world class universities, and our spectacular parks and public spaces. Strong public investments make Washington a good place to live and work, and that’s why we’re consistently ranked as the top state to do business in the nation. If some rapacious jerk doesn’t think he should have to pay a mere seven percent tax on his six-figure Wall Street profits to fund those things, he can shove off to a ‘low-cost’ state like Idaho or Mississippi — oh wait, both those places tax capital gains profits, with fewer exemptions than Washington.

Be kind. Be brave. Take good care of yourself and your loved ones.

Zach