Friends,

Because we are less than one week from Election Day, it’s time to take the American economy’s temperature—to gauge where we are right now and measure what we most need to improve in the next administration. A number of important metrics were published this week that will help us to get a broad economic reading.

First, “Gross domestic product, adjusted for inflation, expanded at a 2.8 percent annual rate in the third quarter,” writes Ben Casselman for the New York Times. That reading “came close to the 3 percent growth rate in the second quarter and was the latest indication that the surprisingly resilient recovery from the pandemic recession remained on solid footing.”

Casselman summed up the economic picture provided by the GDP report this way: “Consumers are spending. Inflation is cooling. And the U.S. economy looks as strong as ever.”

In fact, the paychecks of working Americans have driven that powerful economic growth. Casselman writes that consumer spending “grew at a 3.7 percent rate, adjusted for inflation. Rising wages and low unemployment meant that Americans continued to earn more, while inflation continued to ease: Consumer prices rose at a 1.5 percent annual rate in the third quarter and were up 2.3 percent from a year earlier.”

We must include our regular caveat that GDP numbers don’t report on the entirety of the economy—it measures the topline numbers of the economy, with a focus on the big movers like corporations. That means it’s a better indicator of the economic strength of the corner office, not the households of working Americans. But the fact that consumer spending is robust is a very promising sign—after all, it’s the paychecks of workers that create jobs and economic growth.

The last inflation reading before the election came in this morning, and the news was mostly good. “Inflation has been cooling for two years, and fresh data released on Thursday showed that trend continued in September. Prices climbed just 2.1 percent compared with a year earlier,” writes Jeanna Smialek at the New York Times. “That is nearly back to the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent inflation goal — good news for both the Fed and the White House. It is also slower than the previous reading, which stood at 2.3 percent.” Wage growth continues to come in higher than inflation, meaning that workers have more money in their pockets overall.

And at the same time, Abha Bhattarai at the Washington Post reports, the price of gas is currently plummeting. “Gas prices are averaging $3.14 per gallon nationwide, within 8 cents of a 3-year low,” with prices in the Sun Belt ranging from “$2.70 to $2.90 per gallon.”

In even better news for the nation’s future, Joey Politano reports that “US real investment in wind, solar, and other alternative electricity generation officially hits a new record high this quarter,” creating a pathway to a green-energy future.

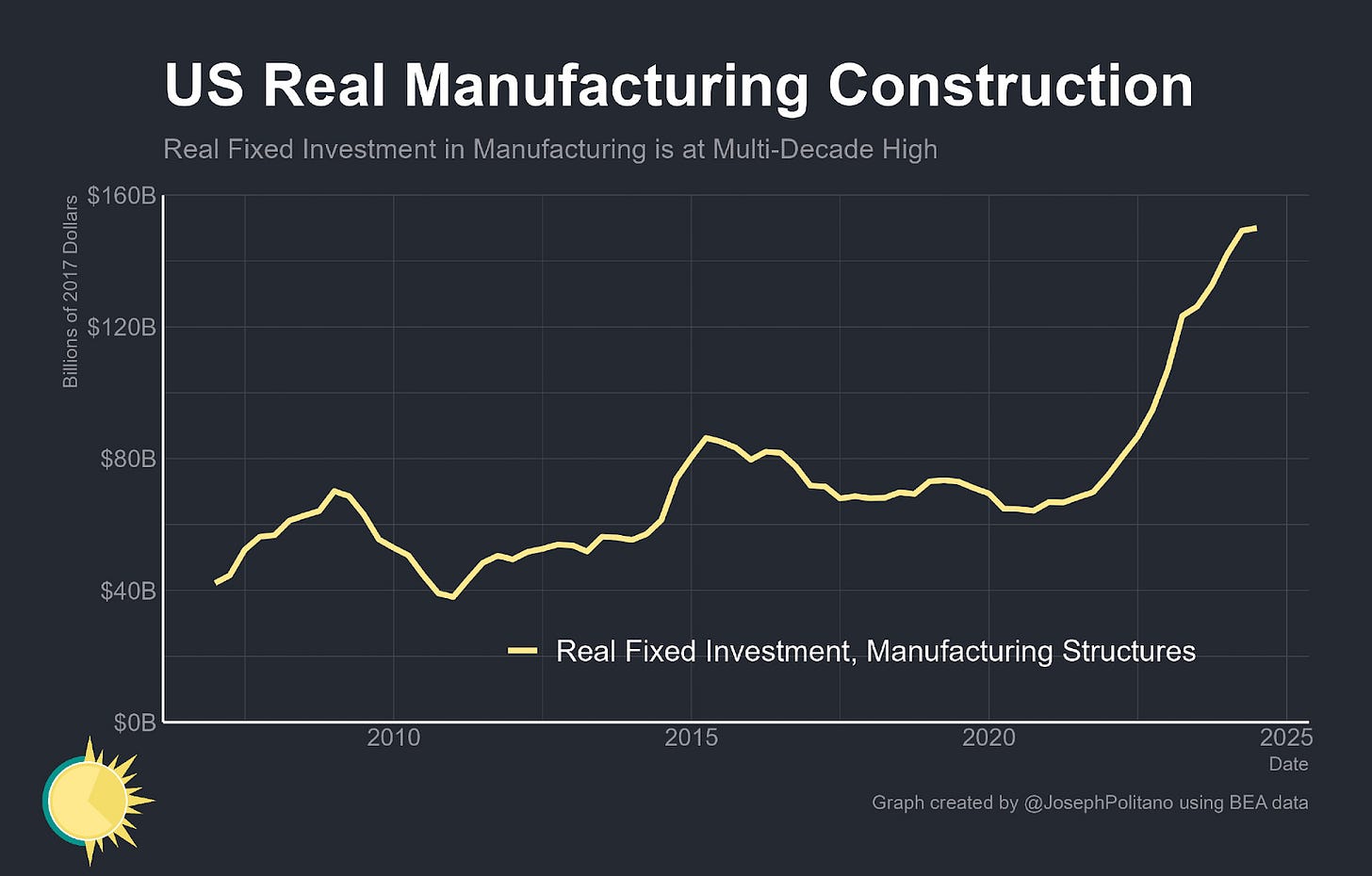

Other Biden Administration investments are starting to pay off. Politano writes that “US real investment in factories, fabs, and other manufacturing structures officially edges up to another record high this quarter,” laying the groundwork for an American manufacturing boom.

In the conclusion of this newsletter, we’ll talk a lot more about those Biden Administration programs and their legacy. But for right now, we have to finish our pre-election economic survey by looking at the weak spots.

Specifically, as we’ve been writing pretty much all year long, the biggest economic problem that America is facing right now is the question of housing affordability.

Casselman writes, “businesses pulled back spending on new buildings, and the housing market contracted for the second straight quarter — signs that high interest rates continue to take a toll. The weakness in housing could continue: Mortgage rates, which fell steadily over the summer, have been rising again in recent weeks.”

The Federal Reserve is set to meet after the election, and most economists predict that they’ll continue to cut interest rates by .25 points. But that slow and steady approach is not enough to bring down mortgage rates fast enough to show benefits for working Americans—and mortgage rates aren’t even the largest contributor to America’s housing affordability problem.

So in summary, it looks like whoever enters the Oval Office next year will have economic winds at their backs in the form of a good job market, growing wages, strong spending, and generally positive economic growth signals across the economy. But they will also face a growing housing crisis as more and more Americans struggle to keep a roof over their heads. With just five days to go before Election Day, that’s the economic issue that all voters should consider before they cast their ballot.

The Latest Economic News and Updates

The Changing Face of Work

As technology and society changes, our relationship with work changes, too. And as work becomes more specialized and knowledge-based, employers prefer some labor pools more than others. The New York Times reports that “In the reordering of the U.S. economy since 1980, white men without a degree have been surpassed in income by college-educated women.”

The main reason for this dramatic shift is largely due to the way our economy has rewarded companies that offshore labor to cheaper nations. But also the way we live our everyday lives have changed. As computers have become dominant in American life, programmer pay has skyrocketed. At the same time, blue-collar workers like factory foremen have seen a dramatic drop in wages, from well above the average American income to well below.

And that shift in value has resulted in a political shift. “Democrats have lost ground with white voters particularly in the places most affected by job losses after NAFTA, a free trade deal, took effect in 1994,” the Times reports. “And in a broader educational realignment underway for decades, college-educated voters have increasingly moved toward the Democratic Party, as voters without a college degree have voted more Republican.”

Ben Casselman reports that we’ve seen another major shift in worker pay just over the last five years. It’s true that American worker wages have increased since pandemic lockdowns ended in 2021, but those paychecks haven’t grown equally.

Casselman notes that “wages have risen fastest for the lowest-paid workers. Inflation-adjusted weekly earnings for the bottom 10 percent of workers in the third quarter this year were up 7.3 percent from the same point in 2019, compared with 3.6 percent for workers at the top.”

“That faster growth at the bottom was driven to a large degree by the strong job market, particularly for workers in the leisure and hospitality sector,” he explains. At the same time, “Workers in other fields made smaller gains, however, and in some cases lost ground relative to prices. Weekly pay, adjusted for inflation, has fallen since 2019 in advertising, telecommunications, chemical manufacturing and a variety of other industries.”

Those reports tend to frame shifts in worker pay as something unchangeable, like the weather. That’s the trickle-down framing of labor’s role in the economy, and it’s not actually true: Government can be a powerful tool for changing the way we recognize our workers. A new bill signed into law in Michigan this month “clear[s] a path for the state’s home care workers to organize a statewide union of more than 35,000 workers as well as standardize care and training,” writes Ethan Bakuli of Capital & Main. This is just the latest step in a long march toward recognizing that home care is essential labor that deserves the same protections as any other health care job.

Also this month, Vice President Harris announced a proposal to cover home care under Medicare. Bakuli explains that the new proposal “would likely increase the number of care workers paid with public funds. Federal data suggest that 29% of people over age 65 — the Medicare eligibility threshold — will require home care at some point; today, that would be about 18 million people. By comparison, Medicaid currently covers home care for 4.2 million people nationwide.” That would be a tremendous—and hugely positive—change for care workers in the economy.

Are Pollsters, Like Economists, Simply Following the Herd?

A couple of days ago, presidential poll-watcher Nate Silver noted on Twitter that “There are too many polls in the swing states that show the race exactly Harris +1, TIE, Trump +1.” Silver pointed out that there “Should be more variance than that.”

Silver is correct—it defies the laws of probability to believe that a wide range of polls could all be landing on the same exact result every single time. A poll is a random sampling of likely or registered voters in a geographic area; there’s no way that all those individual polls could possibly come back with the same results.

As Ed Kilgore explains for Intelligencer, what we’re seeing is likely “poll herding,” in which smaller low-quality polling firms manipulate the findings of their polls to better resemble the results of larger, more reputable polls.

Kilgore quotes political scientist Josh Clinton: “The fact that so many swing state polls are reporting similar close margins is a problem because it raises questions as to whether the polls are tied in these races because of voters or pollsters.”

“Is 2024 going to be as close as 2020 because our politics are stable, or do the polls in 2024 only look like the results of 2020 because of the decisions that state pollsters are making?” Clinton continues, “ The fact that the polls seem more tightly bunched than what we would expect in a perfect polling world raises serious questions about the second scenario.”

What does all this have to do with economics? As Conor Sen pointed out on Silver’s post, “I wonder if the future of polling is going to be like Wall Street economists forecasting econ numbers, where you’re just trying to beat the consensus number by a bit rather than get the number right.”

Perhaps no field is as guilty of herding as economics. Every month, economists agree on predictions for the results of monthly metrics like inflation numbers and unemployment, and their predictions are always more likely to be similar than they are accurate. Or think of how most economists predicted that millions of people would have to lose their jobs for inflation to go back to normal. There are fewer penalties for economists who join the herd than there are rewards for economists who make a bold prediction that then turns out to be right. Unfortunately, this situation results in a lack of expertise in the public square, and less useful information for the general public.

Americans Still Like Their Politicians Unbought

The New York Times notes that Donald Trump has been courting big corporations and super-wealthy people and “making overt promises about what he will do once he’s in office, a level of explicitness toward individual industries and a handful of billionaires that has rarely been seen in modern presidential politics.”

Trump ran in 2016 as an outsider who was too rich to be bought. But this year, the Times writes, “Mr. Trump has sought to shake loose cash from industries like oil and energy that have long aligned with his deregulation agenda. In others, Mr. Trump has flipped his positions, such as on crypto.”

One of Trump’s highest-profile donors lately has been Elon Musk. For the Times, Jack Ewing explains how Musk might use his support to manipulate a potential second Trump Administration into protecting all the subsidies that fund his sprawling empire, including the clean air credits from the Environmental Protection Agency that Tesla sells for hundreds of millions of dollars. (In the third quarter of this year, the $739 million in clean air credits that Tesla sold amounted to a full third of the company’s profit for the quarter.)

The voting public often suspects that these kinds of transactional deals are happening between big-money donors and politicians, but Trump’s public embrace of the deals are unique. Generally, politicians do a better job of hiding the quid pro quo because being bought and sold for influence is unpopular.

Right now in Nebraska, a tight race between incumbent Republican Senator Deb Fischer and upstart independent Dan Osborn is raising eyebrows. Nebraska has for decades been seen as a safe Republican seat, but Osborn—a union leader who is running on a populist platform—has inspired questions over how much influence Big Agriculture has over Fischer.

David Dayen writes at the American Prospect, “In 2021, Fischer, a member of the Senate Agriculture Committee since 2018, intervened to significantly weaken a bill about cattle prices that the agribusiness lobby opposed. The resulting compromise never passed, meaning that ranchers who for decades have been pleading with Washington to deal with sagging revenues for their operations are still waiting for relief.”

According to independent ranchers, “Fischer took the side of the dominant meatpackers, longtime donors of over $1.5 million across her Senate career, who have been stiffing those ranchers while earning record profits.”

That direct line between corporate meat packers and Fischer’s pockets has been a major issue in her campaign, and a leading argument in Osborn’s advertisements. People still don’t like it when their elected leaders do the bidding of the wealthy and powerful in exchange for big paychecks.

This Week in Middle Out

It’s become a culture-wide joke that you can never buy ice cream at McDonald’s when you want it. The machines seem to be perennially out of service and in need of repair. But it turns out that the machines aren’t especially complicated to fix; the problem was that McDonald’s franchisees didn’t have the right to repair their own machines. McDonald’s held proprietary control over every aspect of the ice cream makers, including the repair process. A new regulation proposed by the FTC and Department of Justice would vastly expand the right of individuals to repair equipment that they own, thereby making it easier for McDonald’s franchises to repair their machines in a timely manner. They write that “renewing and expanding repair-related exemptions would promote competition in markets for replacement parts, repair, and maintenance services, as well as facilitate competition in markets for repairable products. Promoting competition in repair markets benefits consumers and businesses by making it easier and cheaper to fix things they own.”

Thanks to a new Department of Transportation rule, “As of Monday, Oct. 28, you are automatically entitled to a full refund for a flight that has been canceled or delayed by more than 3 hours for a domestic itinerary or 6 hours for an international one,” reports Frommers.

“The Environmental Protection Agency finalized a rule Thursday to tighten lead dust standards, a move that aims to eliminate decades-old paint in millions of homes across the country that endangers young children,” writes the Washington Post.

Speaking of the EPA: if Donald Trump wins re-election, the future of the Environmental Protection Agency is in doubt. Trump’s allies “have said they will do a more methodical job of reversing climate policies than they did in his first term, when they rolled back more than 100 environmental policies and regulations they said were hampering the economy, only to watch from the sidelines as President Biden restored most of them.”

With the recent Boar’s Head, frozen waffle, and McDonald’s food contaminant outbreaks, it might feel like there’s more bad food in the system. In fact, Vox argues that we’re hearing about these outbreaks because of better government oversight, “thanks to legislation around food safety modernization. That makes it easier for the Food and Drug Administration, one of the bodies that investigates such outbreaks, to track problems to their source. It also makes it easier for companies to recall tainted products before they spread further into the food system and sicken large numbers of people.”

This Axios interview with Securities Exchange Commission head Gary Gensler is an interesting look at a public servant who is proud of the work he’s done over the last four years. Gensler says he had 50 projects in mind when he took office, ranging from regulating bitcoin to establishing rules for corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance disclosures, and that he’d completed “about 45” of them already.

This Week on the Pitchfork Economics Podcast

For the Halloween episode of Pitchfork Economics, Goldy and Paul talk with Peggy Bailey from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities about the Republican House budget plan and Project 2025. Bailey read every single page of the two biggest national Republican policy platforms and helped author a report on what those policies would do to working American families. You’ll have to listen to the episode for Bailey’s full report, but in short: The trickle-down Republican economic policies on the ticket this year would make the wealthiest few even richer, while also stripping wealth away from the poorest working Americans.

Closing Thoughts

In the New Yorker this week, Nicholas Lemann asks an important question: “Bidenomics is starting to transform America. Why has no one noticed?”

Lemann opens with Biden’s 2020 presidential victory. Then, he writes, “with nothing close to a mandate, Biden passed domestic legislation that will generate government spending of at least five trillion dollars, spread across a wide range of purposes, in every corner of the country. He has also redirected many of the federal government’s regulatory agencies in ways that will profoundly affect American life.”

Lemann continues, “On Biden’s watch, the government has launched large programs to move the country to clean energy sources, to create from scratch or to bring onshore a number of industries, to strengthen organized labor, to build thousands of infrastructure projects, to embed racial-equity goals in many government programs, and to break up concentrations of economic power.”

“All of this doesn’t represent merely a hodgepodge of actions,” Lemann writes. “There is as close to a unifying theory as one can find in a sweeping set of government policies…Real Bidenomics upends a set of economic assumptions that have prevailed in both parties for most of the past half century.”

Lemann explains that Biden sees government “as the designer and ongoing referee of markets, rather than as the corrector of markets’ dislocations and excesses after the fact.” He says that Biden is the first Democrat in decades to ask questions about free trade and globalization, and the first in decades to use the presidency’s sweeping antitrust powers, and the first Democrat in the Oval Office to not promote green energy through carbon credits.

Lemann follows Biden Administration officials around the country as they prepare infrastructure projects and break ground on factories, and he digs into the presidential campaign of 2020 in order to find out what makes Biden, in his own phrasing, the first “post-neoliberal” president.

Of course, none of this is news to regular readers of The Pitch. We’ve been talking about President Biden’s middle-out economic agenda since day one, and we’ve pointed out that Biden directly targets trickle-down economics— the less polite terminology for “neoliberalism”—at every opportunity.

The question in Lemann’s headline, about why nobody has noticed the transformational aspect of Biden’s economic plans, is a bit misleading. While it’s true that enough of the seeds planted by the Biden Administration over the last four years will take years to bear fruit that prospective voters will be able to appreciate, the fact is that the American people have noticed this shift in the economic atmosphere.

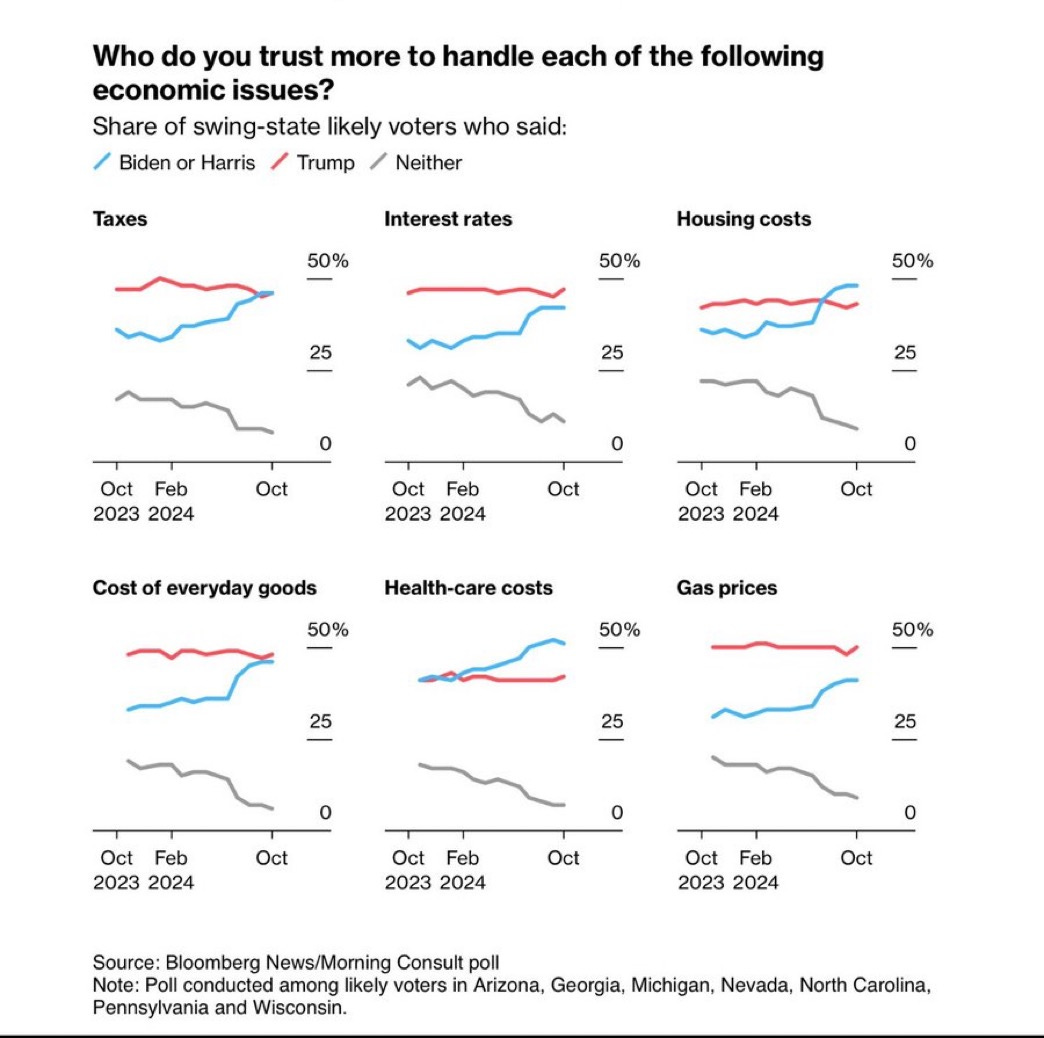

The New York Times recently published a report showing that voter trust for Vice President Kamala Harris on economic issues has grown at a very rapid clip. While she started the race down 13% when compared to Trump’s economic job performance, that gap has closed by more than half over the last two months.

Where have those positive numbers come from? The Times says her improvement was “primarily concentrated among nonwhite voters, particularly nonwhite voters without a college degree.” After years of inattention from Democratic and Republican presidents alike, those are some of the working Americans who the Biden Administration has worked hardest to serve with their policies that grow paychecks and make deep investments in infrastructure, manufacturing, and other improvements.

Bloomberg found even more interesting results when it dug deeper into specific economic issues. Harris has closed the gap or exceeded Trump when it comes to vital election issues like housing costs, cost of goods, and healthcare costs.

For Time, Phillip Elliott writes that “Harris’ gains may be even more pronounced in the places she needs it most. Right after Biden bowed out, the center-left pollsters Redfield and Wilton found Trump leading Harris on the economy in the seven core swing states, Trump showed to be anywhere from six points ahead on that question in Michigan to 13 points in Pennsylvania. These days, they find Harris is favored on the economy in three of those states and tied in another two. “

While not every American pays deep attention to the kind of economic metrics we talked about in the opening of this email, they do know whether their paychecks are growing or shrinking. They can see if their friends and family are struggling or thriving. They know if they feel like the economy is rigged against them. Harris’s ads have done an excellent job of speaking to all those factors and framing her as someone who believes the middle class is the source of America’s economic prosperity. I’d argue that these polls mark the very beginning of an economic realignment toward middle-out economics, and that Bidenomics has already started to turn the tide against trickle-down economics.

Onward and upward—and please remember to vote.

Zach